EAL – Operation Fake Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Observed Residual Error Structure Yields the Best Estimates of Individual Growth Parameters

fishes Article Using Observed Residual Error Structure Yields the Best Estimates of Individual Growth Parameters Marcelo V. Curiel-Bernal 1,2, E. Alberto Aragón-Noriega 2 , Miguel Á. Cisneros-Mata 1,* , Laura Sánchez-Velasco 3, S. Patricia A. Jiménez-Rosenberg 3 and Alejandro Parés-Sierra 4 1 Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura, Calle 20 No. 605-Sur, Guaymas 85400, Sonora, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Unidad Guaymas del Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C. Km 2.35 Camino a El Tular, Estero de Bacochibampo, Guaymas 85454, Sonora, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Instituto Politécnico Nacional-Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Av. Instituto Politécnico Nacional s/n, Playa Palo de Santa Rita, La Paz 23096, Baja California Sur, Mexico; [email protected] (L.S.-V.); [email protected] (S.P.A.J.-R.) 4 Departamento de Oceanografía Física, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada 3918, Ensenada 22860, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-622-22-25925 Abstract: Obtaining the best possible estimates of individual growth parameters is essential in studies of physiology, fisheries management, and conservation of natural resources since growth is a key component of population dynamics. In the present work, we use data of an endangered fish species to demonstrate the importance of selecting the right data error structure when fitting growth models in multimodel inference. The totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) is a fish species endemic to the Gulf of Citation: Curiel-Bernal, M.V.; California increasingly studied in recent times due to a perceived threat of extinction. -

Endangered Species (Protection, Conser Va Tion and Regulation of Trade)

ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSER VA TION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) THE ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Preliminary Short title. Interpretation. Objects of Act. Saving of other laws. Exemptions, etc., relating to trade. Amendment of Schedules. Approved management programmes. Approval of scientific institution. Inter-scientific institution transfer. Breeding in captivity. Artificial propagation. Export of personal or household effects. PART I. Administration Designahem of Mana~mentand establishment of Scientific Authority. Policy directions. Functions of Management Authority. Functions of Scientific Authority. Scientific reports. PART II. Restriction on wade in endangered species 18. Restriction on trade in endangered species. 2 ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULA TION OF TRADE) Regulation of trade in species spec fled in the First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedules Application to trade in endangered specimen of species specified in First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Importation of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Introduction from the sea certificate for specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Introduction from the sea of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Export of specimens specified in Fourth Schedule. PART 111. -

中国水学校 Waterschool China

中国水学校 Waterschool China China Ministry of Education PROJECT IMPLEMENTATED BY BACKGROUND 4 PROJECT RATIONALE 6 PROJECT IMPACT 8 香格里拉可持续社区学会 HISTORY 10 LOCATIONS 11 RIVER BASIN DESCRIPTIONS 12 KEY PARTNERS INTRO TO ESD 20 MILESTONES 26 CASE STUDIES 30 National Centre for School Curriculum and Textbook Development: CHILDREN’S PARTICIPATION 44 Ministry of Education of China (MOE-NCCT) STRATEGY 46 MANAGEMENT STURCTURE 47 UNESCO Beijing Offi ce Education for a Sustainable China (the National ESD Association) BACKGROUND VISION People living in harmony with nature across China Th e Greater Shangri-la RCE acts as a regional hub, linking ESD stakeholders in the region in order to link with other ESD organisations nationally and internationally. A diverse group of 27 members form GOAL the Greater Shangri-la RCE, of which the Shangri-la Institute for Restore the ecological integrity of the rivers in China through eff ec- Sustainable Communities (SISC) is a key facilitator. Th e RCE has tive public participation in sustainable water resource management. been built around the projects, networks, funding and staff of SISC and has a similar management system. PURPOSE One such project is the Waterschool China programme, a component Foster environmental stewardship in selected watersheds through of the International Water School Programme initiated in Austria participatory learning and action by schools and communities, con- by Swarovski. Th e project has been implemented by SISC and other tributing to improved social and environmental conditions in river Greater Shangri-la Members in China since 2008, and seeks to basins and beyond. educate school students and engage communities throughout the Yangtze basin in ways that enable them to become active participants in sustainable water resource management. -

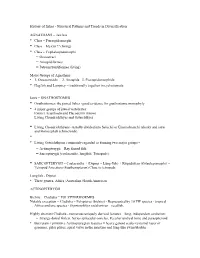

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

2018 IUCN SSC Scianenid RLA Report

IUCN SSC Sciaenidae Red List Authority 2018 Report Orangel Aguilera Ying Giat Seah Co-Chairs Mission statement Targets for the 2017-2020 quadrennium Ning Labbish Chao (1) (Previous Co-Chair) The mission of the IUCN SSC Sciaenidae Red List Assess (2) Min Liu (Previous Co-Chair) Authority is to revise and submit the assess- Red List: (1) organise a Red List assessment (3) Orangel Aguilera (2018 Elected Co-Chair) ments of all 300 species of sciaenid fishes and and training workshop, planned for 25–29 (4) Ying Giat Seah (2018 Elected Co-Chair) to redefine the goal of the second phase of the September 2018, at the Universiti Malaysia Global Sciaenidae Conservation Plan. Terengganu, Malaysia (expecting 50 members Red List Authority Coordinators to participate); (2) complete submission of Orangel Aguilera (3) (Brazil, South America) Projected impact for the 2017-2020 global Sciaenidae Red List assessments; (3) Ying Giat Seah (4) (Malaysia, Asia) quadrennium final revision of global Sciaenidae Red List By the end of 2020, we will complete the first assessments. Location/Affiliation global assessment of sciaenid fishes and (1) Bio-Amazonia Conservation International, will submit it to IUCN for final publication. A Activities and results 2018 Brookline, MA, US; National Museum of Marine significant threat to Sciaenidae conservation Assess Biology, Taiwan, Province of China has become more prominent since 2016 due Red List (2) Xiamen University, Xiamen, China to the popularity of Sciaenid Maws (dried gas i. We organised the Third Sciaenidae Red List (3) Departamento de Biologia Marinha (GBM), bladder) for food and medicinal use in Asian Assessment Workshop, entitled ‘International Universidade Federal do Fluminense, countries. -

SC71 Inf. 2 (English and Spanish Only / Únicamente En Inglés Y Español / Seulement En Anglais Et Espagnol)

Original language: English and Spanish SC71 Inf. 2 (English and Spanish only / únicamente en inglés y español / seulement en anglais et espagnol) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventy-first meeting of the Standing Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 16 August 2019 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING THE REGISTRATION OF THE OPERATION “EARTH OCEAN FARMS. S. DE R.L. DE C.V.” BREEDING TOTOABA MACDONALDI 1. This document has been submitted by Mexico in relation to agenda item 17.* 2. This document contains additional and more detailed information to that presented in the Earth Ocean Farms Registration application (the application can be consulted in full in SC71 Doc. 17, Annex 1a), as well as the response to the comments of the Animals Committee (SC71 Doc. 17, Annex 4a). In addition, Mexico has submitted summaries of law enforcement measures for totoaba in the wild that can be found in the document SC70 Doc. 62.2 R1. 1. Conservation status of wild totoaba and its legal use in Mexico 1.1. History and fishing ban The totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) is distributed in the most important and productive fishing zone in Mexico (Gulf of California). In 1920, the fishing of this species influenced the establishment of fishing villages in the Upper Gulf, but it was until 1929 that it was commercially exploited, increasing fishing to 2,000 tons per year between 1940-1950, for meat consumption. In 1955, the government of Mexico established a seasonal ban to protect the breeding areas in the critical stages (mouth of the Colorado River); in 1974, this area was decreed a Reserve for the species subject to fishing. -

Focus Group on Status and Trends and Red List Assessment Final Report

Focus Group on Status and Trends and Red List Assessment Final Report 1. Relevant Aichi Biodiversity targets Aichi Target 19 - Biodiversity Knowledge By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied. Aichi Target 12 - Preventing Extinction By 2020, the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained. Other relevant Aichi Targets are 1 (Awareness of Biodiversity Values), 2 (Integration of Biodiversity Values) , 5 (Loss of Habitats), 6 (Sustainable Fisheries), 7 (Areas under Sustainable Management), 8 (Pollution), 9 (Invasive Alien Species), 11 (Protected Areas), 14 (Essential Ecosystem Services) and 20 (Resource Mobilisation) 2. Leaders - Dr Michael Lau (WWF-HK) and Prof. Yvonne Sadovy (HKU) 3. Key experts/stakeholders involved in the discussions (a) Within the Steering Committee/Working Groups - Dr Gary Ades (KFBG), Prof Put Ang Jr. (CUHK), Mr Simon Chan (AFCD), Dr Andy Cornish (WWF-International), Prof. David Dudgeon (HKU), Dr Billy Hau (HKU), Dr Roger Kendrick, Mr Kevin Laurie (Hong Kong Coast Watch), Ms Samantha Lee (WWF-HK), Ms Louise Li (AFCD), Dr Ng Cho Nam (HKU), Dr Paul Shin (City U), Mr Samson So (Eco Institute), Prof. Nora Tam (City U), Mr Tam Po Yiu, Dr Jackie Yip (AFCD) (b) Outside the Steering Committee/Working Groups - Mr John Allcock (WWF-HK), Ms Aidia Chan (AFCD), Mr Christophe Barthelemy, Mr Geoff Carey (AEC), Dr John Fellowes (KFBG), Dr Stephan Gale (KFBG), Dr David Gallacher (AECOM), Dr Leszek Karczmarski (HKU), Dr Pankaj Kumar (KFBG), Mr Paul Leader (AEC), Ms Janet Lee (AFCD), Dr Michael Leven (AEC), Ms Angie Ng (CA), Dr Ng Sai-chit (AFCD), Mr Tony Nip (KFBG), Mr Stan Shea, Ms Shadow Sin (OPCF), Ms Ivy So (AFCD), Mr Ray So, Dr Sung Yik Hei (KFBG), Dr Alvin Tang (Muni Arborist Ltd), Dr Allen To (WWF-HK), Mr Yu Yat Tung (HKBWS) 4. -

Totoaba Pelly Petition

September 29, 2014 Via Certified Mail and Electronic Mail Penny Pritzker Sally Jewell Secretary of Commerce Secretary of the Interior 1401 Constitution Avenue, N.W. 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20230 Washington, DC 20240 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dr. Jean-Pierre Plé Bryan Arroyo Acting Director Assistant Director for International Affairs Office of International Affairs U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Marine Fisheries Service 5275 Leesburg Pike 1315 East-West Highway Falls Church, VA 22041 SSMC3, 10th Floor F/IA Email: [email protected] Silver Springs, MD 20910 Email: [email protected] Re: Petition for Certification of Mexico pursuant to the Pelly Amendment for Trade in Violation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species Dear Secretary Pritzker, Secretary Jewell, Dr. Plé, and Director Arroyo, The Center for Biological Diversity (“the Center”) submits this petition requesting certification of Mexico pursuant to the Pelly Amendment. 22 U.S.C. § 1978. Specifically, the Center seeks certification that Mexico’s failure to stem the growing trade and export of endangered totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) “diminishes the effectiveness” of the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (“CITES”),1 as it simultaneously drives the critically endangered vaquita to extinction. Id. § 1978(a)(2). The Center requests that the Secretaries recommend trade sanctions against Mexico for these violations, as contemplated by the Pelly Amendment. Id. § 1978(a)(4).2 As described in detail below, the totoaba is a large, critically endangered fish found only in Mexico’s Gulf of California. -

Overview of the Pearl River Delta

Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study Leung Sze-lun, Alan Research Team: Leung Sze-lun, Alan Chung Hoi-yan Tong Xiaoli Published in July 2007 by WWF Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR Supported by Epson Foundation Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to particularly acknowledge the generous support by Epson Foundation in funding WWF Hong Kong to conduct this study. I am grateful to all officials from Hong Kong and Guangdong who shared their views on freshwater issues during this study, also researchers, academics, environmentalists and nature lovers. I thank Professor David Dudgeon and Professor Richard Corlett from the Department of Ecology & Biodiversity, The University of Hong Kong for their comments on the drafts of the report. I also thank the Freshwater team from WWF China on their comments on the report. Special thanks should be given to Dr. Tong Xiaoli and his students from the South China Agricultural University and Ms. Chung Hoi-yan for their very hard work on literature collection, data inputs, field work, and conducting interviews for this report. Epson Pearl River Delta Scoping Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Freshwater ecosystems are considered amongst the world’s most endangered ecosystems. The freshwater crisis facing the world today is one of the most serious global environmental challenges to both man and biodiversity. Freshwater issues in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) in Guangdong, China are considered to be a significant challenge to the future development of the region. The objectives of this report are to better understand the complex linkages among the various threats to freshwater biodiversity, and their causes, in order to identify opportunities and strategies for reducing these threats through future conservation actions in the region. -

Otolith-Based Growth Estimates and Insights Into Population Structure Of

Fisheries Research 161 (2015) 374–383 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fishres Otolith-based growth estimates and insights into population structure of White Seabass, Atractoscion nobilis, off the Pacific coast of North America a a,∗ a Alfonsina E. Romo-Curiel , Sharon Z. Herzka , Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki , b b Chugey A. Sepulveda , Scott A. Aalbers a Departamento de Oceanografía Biológica, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), No. 3918 Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Ensenada, Baja California CP 22860, Mexico b Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research (PIER), 2110 South Coast Highway Suite F, Oceanside, CA 92054, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: White Seabass (Atractoscion nobilis; Sciaenidae) comprise an important commercial resource in the USA Received 27 March 2014 and Mexico, but there are few growth rate estimates and its population structure remains uncertain. Received in revised form 29 August 2014 Growth rates were estimated based on otolith analysis of fish collected at three locations spanning 1000- Accepted 1 September 2014 km. Variations in growth rates were assessed at the population level and by reconstructing individual Handling Editor B. Morales-Nin growth trajectories. Seabass were sampled from fisheries operating off southern California (SC) and the northern and southern (NBC and SBC) Baja California peninsula from 2009 to 2012 (n = 415). Ages ranged Keywords: from 0 to 28-years, but fish >21-years of age were sampled infrequently. Size-at-age was highly vari- Otolith able, particularly for fish <5-years. -

List of Annexes to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Partnership Agreement

List of Annexes to The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Partnership Agreement Annex 1: Composition and Terms of Reference of the Red List Committee and its Working Groups (amended by RLC) Annex 2: The IUCN Red List Strategic Plan: 2017-2020 (amended by RLC) Annex 3: Rules of Procedure for IUCN Red List assessments (amended by RLC, and endorsed by SSC Steering Committee) Annex 4: IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, version 3.1 (amended by IUCN Council) Annex 5: Guidelines for Using The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (amended by SPSC) Annex 6: Composition and Terms of Reference of the Red List Standards and Petitions Sub-Committee (amended by SSC Steering Committee) Annex 7: Documentation standards and consistency checks for IUCN Red List assessments and species accounts (amended by Global Species Programme, and endorsed by RLC) Annex 8: IUCN Red List Terms and Conditions of Use (amended by the RLC) Annex 9: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Logo Guidelines (amended by the GSP with RLC) Annex 10: Glossary to the IUCN Red List Partnership Agreement Annex 11: Guidelines for Appropriate Uses of Red List Data (amended by RLC) Annex 12: MoUs between IUCN and each Red List Partner (amended by IUCN and each respective Red List Partner) Annex 13: Technical and financial annual reporting template (amended by RLC) Annex 14: Guiding principles concerning timing of publication of IUCN Red List assessments on The IUCN Red List website, relative to scientific publications and press releases (amended by the RLC) * * * 16 Annex 1: Composition and Terms of Reference of the IUCN Red List Committee and its Working Groups The Red List Committee is the senior decision-making mechanism for The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. -

Appendix 13.5 Marine Ecology Field Survey Result Excluding CWD

Expansion of Hong Kong International Airport into a Three-Runway System Environmental Impact Assessment Report Appendix 13.5 Marine Ecology Field Survey Result Excluding CWD 308875/ENL/ENL/03/07/C March 2014 P:\Hong Kong\ENL\PROJECTS\308875 3rd runway\03 Deliverables\07 Final EIA Report\Appendices\Ch 13 Marine Ecology\Appendix 13.5 Marine Ecological Field Survey Result (Excluding CWD).doc 1 Expansion of Hong Kong International Airport into a Three-Runway System Environmental Impact Assessment Report 1. Baseline Conditons of Subtidal Shore and Coral Communities The marine waters in the North Western Water Control Zone support both subtidal hard and soft bottom assemblages. The locations with coral communities of conservation importance recorded are shown in the habitat maps Drawing No. MCL/P132/EIA/13-014 to Drawing No. MCL/P132/EIA/13-020 . 1.1 Subtidal Hard Bottom Assemblages Spot dive surveys and rapid ecological assessments (REAs) at 16 coral survey points for hard bottom coral were undertaken between August 2012and September 2013. Dates for the hard-bottom and soft-bottom coral spot-check dive surveys and REAs are given in Table 1.1. Table 1-1: Dates for coral-check dive surveys and REAs (hard-bottom and soft-bottom) Hard-bottom Soft-bottom Location Date Location Date D1 9 Aug 2012 C1 10 May 2013 D2 9 Aug 2012 C2 14 May 2013 D3 9 Aug 2012 C3 14 May 2013 D4 9 Aug 2012 C4 9 May 2013 D5 9 Aug 2012 C5 9 May 2013 D6 9 Aug 2012 C6 24 May 2013 D7 9 Aug 2012 C7 24 May 2013 D8 9 Aug 2012 C8 10 May 2013 D9 2 Sept 2013 C9 10 May 2013 D10 31 Jul 2013 C10 10 May 2013 D11 31 Jul 2013 C11 24 May 2013 D12 4 Aug 2013 C12 10 May 2013 D13 4 Aug 2013 C13 14 May 2013 D14 31 Jul 2013 C14 14 May 2013 D15 11 Sept 2013 C15 21 May 2013 D16 2 Sept 2013 C16 21 May 2013 - C17 9 May 2013 - C18 9 May 2013 - C19 21 May 2013 - SC2 21 May 2013 - SC10 15 May 2013 - SC12 10 May 2013 Detailed findings of the hard bottom coral dive surveys are provided in Annex A1.