Totoaba Pelly Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Observed Residual Error Structure Yields the Best Estimates of Individual Growth Parameters

fishes Article Using Observed Residual Error Structure Yields the Best Estimates of Individual Growth Parameters Marcelo V. Curiel-Bernal 1,2, E. Alberto Aragón-Noriega 2 , Miguel Á. Cisneros-Mata 1,* , Laura Sánchez-Velasco 3, S. Patricia A. Jiménez-Rosenberg 3 and Alejandro Parés-Sierra 4 1 Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura, Calle 20 No. 605-Sur, Guaymas 85400, Sonora, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Unidad Guaymas del Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C. Km 2.35 Camino a El Tular, Estero de Bacochibampo, Guaymas 85454, Sonora, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Instituto Politécnico Nacional-Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Av. Instituto Politécnico Nacional s/n, Playa Palo de Santa Rita, La Paz 23096, Baja California Sur, Mexico; [email protected] (L.S.-V.); [email protected] (S.P.A.J.-R.) 4 Departamento de Oceanografía Física, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada 3918, Ensenada 22860, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-622-22-25925 Abstract: Obtaining the best possible estimates of individual growth parameters is essential in studies of physiology, fisheries management, and conservation of natural resources since growth is a key component of population dynamics. In the present work, we use data of an endangered fish species to demonstrate the importance of selecting the right data error structure when fitting growth models in multimodel inference. The totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) is a fish species endemic to the Gulf of Citation: Curiel-Bernal, M.V.; California increasingly studied in recent times due to a perceived threat of extinction. -

Endangered Species (Protection, Conser Va Tion and Regulation of Trade)

ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSER VA TION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) THE ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Preliminary Short title. Interpretation. Objects of Act. Saving of other laws. Exemptions, etc., relating to trade. Amendment of Schedules. Approved management programmes. Approval of scientific institution. Inter-scientific institution transfer. Breeding in captivity. Artificial propagation. Export of personal or household effects. PART I. Administration Designahem of Mana~mentand establishment of Scientific Authority. Policy directions. Functions of Management Authority. Functions of Scientific Authority. Scientific reports. PART II. Restriction on wade in endangered species 18. Restriction on trade in endangered species. 2 ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULA TION OF TRADE) Regulation of trade in species spec fled in the First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedules Application to trade in endangered specimen of species specified in First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Importation of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Introduction from the sea certificate for specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Introduction from the sea of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Export of specimens specified in Fourth Schedule. PART 111. -

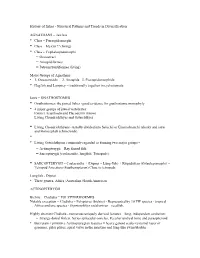

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

2018 IUCN SSC Scianenid RLA Report

IUCN SSC Sciaenidae Red List Authority 2018 Report Orangel Aguilera Ying Giat Seah Co-Chairs Mission statement Targets for the 2017-2020 quadrennium Ning Labbish Chao (1) (Previous Co-Chair) The mission of the IUCN SSC Sciaenidae Red List Assess (2) Min Liu (Previous Co-Chair) Authority is to revise and submit the assess- Red List: (1) organise a Red List assessment (3) Orangel Aguilera (2018 Elected Co-Chair) ments of all 300 species of sciaenid fishes and and training workshop, planned for 25–29 (4) Ying Giat Seah (2018 Elected Co-Chair) to redefine the goal of the second phase of the September 2018, at the Universiti Malaysia Global Sciaenidae Conservation Plan. Terengganu, Malaysia (expecting 50 members Red List Authority Coordinators to participate); (2) complete submission of Orangel Aguilera (3) (Brazil, South America) Projected impact for the 2017-2020 global Sciaenidae Red List assessments; (3) Ying Giat Seah (4) (Malaysia, Asia) quadrennium final revision of global Sciaenidae Red List By the end of 2020, we will complete the first assessments. Location/Affiliation global assessment of sciaenid fishes and (1) Bio-Amazonia Conservation International, will submit it to IUCN for final publication. A Activities and results 2018 Brookline, MA, US; National Museum of Marine significant threat to Sciaenidae conservation Assess Biology, Taiwan, Province of China has become more prominent since 2016 due Red List (2) Xiamen University, Xiamen, China to the popularity of Sciaenid Maws (dried gas i. We organised the Third Sciaenidae Red List (3) Departamento de Biologia Marinha (GBM), bladder) for food and medicinal use in Asian Assessment Workshop, entitled ‘International Universidade Federal do Fluminense, countries. -

SC71 Inf. 2 (English and Spanish Only / Únicamente En Inglés Y Español / Seulement En Anglais Et Espagnol)

Original language: English and Spanish SC71 Inf. 2 (English and Spanish only / únicamente en inglés y español / seulement en anglais et espagnol) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventy-first meeting of the Standing Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 16 August 2019 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING THE REGISTRATION OF THE OPERATION “EARTH OCEAN FARMS. S. DE R.L. DE C.V.” BREEDING TOTOABA MACDONALDI 1. This document has been submitted by Mexico in relation to agenda item 17.* 2. This document contains additional and more detailed information to that presented in the Earth Ocean Farms Registration application (the application can be consulted in full in SC71 Doc. 17, Annex 1a), as well as the response to the comments of the Animals Committee (SC71 Doc. 17, Annex 4a). In addition, Mexico has submitted summaries of law enforcement measures for totoaba in the wild that can be found in the document SC70 Doc. 62.2 R1. 1. Conservation status of wild totoaba and its legal use in Mexico 1.1. History and fishing ban The totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi) is distributed in the most important and productive fishing zone in Mexico (Gulf of California). In 1920, the fishing of this species influenced the establishment of fishing villages in the Upper Gulf, but it was until 1929 that it was commercially exploited, increasing fishing to 2,000 tons per year between 1940-1950, for meat consumption. In 1955, the government of Mexico established a seasonal ban to protect the breeding areas in the critical stages (mouth of the Colorado River); in 1974, this area was decreed a Reserve for the species subject to fishing. -

EAL – Operation Fake Gold

OPERATION FAKE GOLD Executive Summary The vaquita, the world’s smallest and most endangered porpoise, is nearly extinct due to China’s demand for the swim bladders, or ‘maws,’ from a giant Mexican fish called the totoaba. By-catch from the Illegal fishing of totoabas with the use of gillnets is killing vaquitas. In fact, the use of gillnets for illegal totoaba fishing is endangering the entire marine ecosystem in the Upper Gulf of California. The International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) estimated that, as of November 2016, no more 1. “CIRVA 10 Final than 30 vaquitas remained. Analysis of 2017 acoustic monitoring data showed that the Report 2018.” decline of the vaquita has continued unabated.1 In response to these dire circumstances, Elephant Action League (EAL) commenced an investigation and intelligence gathering operation, called Operation Fake Gold, to map the entire illicit totoaba maw supply chain in March 2017. The 14-month investigation took EAL’s Wildlife Crime Division agents from the Baja California peninsula to South- ern China’s Guangdong Province. Head of the vaquita In China, fish maw has become a favorite ingredient for cuisine served at special oc- underwater casions, such as birthdays, weddings, and Chinese New Year; is presented as gifts for (credit: Terra Mater similar occasions; is purchased as an investment; and is processed into skincare prod- Factual Studios/Ri- ucts. The retail price of totoaba maw has been recently quoted up to USD 46 per gram chard Ladkani) in China. The price of gold is hovering around USD 40 (5 July 2018) per gram. -

Otolith-Based Growth Estimates and Insights Into Population Structure Of

Fisheries Research 161 (2015) 374–383 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fisheries Research j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fishres Otolith-based growth estimates and insights into population structure of White Seabass, Atractoscion nobilis, off the Pacific coast of North America a a,∗ a Alfonsina E. Romo-Curiel , Sharon Z. Herzka , Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki , b b Chugey A. Sepulveda , Scott A. Aalbers a Departamento de Oceanografía Biológica, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), No. 3918 Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Ensenada, Baja California CP 22860, Mexico b Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research (PIER), 2110 South Coast Highway Suite F, Oceanside, CA 92054, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: White Seabass (Atractoscion nobilis; Sciaenidae) comprise an important commercial resource in the USA Received 27 March 2014 and Mexico, but there are few growth rate estimates and its population structure remains uncertain. Received in revised form 29 August 2014 Growth rates were estimated based on otolith analysis of fish collected at three locations spanning 1000- Accepted 1 September 2014 km. Variations in growth rates were assessed at the population level and by reconstructing individual Handling Editor B. Morales-Nin growth trajectories. Seabass were sampled from fisheries operating off southern California (SC) and the northern and southern (NBC and SBC) Baja California peninsula from 2009 to 2012 (n = 415). Ages ranged Keywords: from 0 to 28-years, but fish >21-years of age were sampled infrequently. Size-at-age was highly vari- Otolith able, particularly for fish <5-years. -

List of Annexes to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Partnership Agreement

List of Annexes to The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Partnership Agreement Annex 1: Composition and Terms of Reference of the Red List Committee and its Working Groups (amended by RLC) Annex 2: The IUCN Red List Strategic Plan: 2017-2020 (amended by RLC) Annex 3: Rules of Procedure for IUCN Red List assessments (amended by RLC, and endorsed by SSC Steering Committee) Annex 4: IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, version 3.1 (amended by IUCN Council) Annex 5: Guidelines for Using The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (amended by SPSC) Annex 6: Composition and Terms of Reference of the Red List Standards and Petitions Sub-Committee (amended by SSC Steering Committee) Annex 7: Documentation standards and consistency checks for IUCN Red List assessments and species accounts (amended by Global Species Programme, and endorsed by RLC) Annex 8: IUCN Red List Terms and Conditions of Use (amended by the RLC) Annex 9: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ Logo Guidelines (amended by the GSP with RLC) Annex 10: Glossary to the IUCN Red List Partnership Agreement Annex 11: Guidelines for Appropriate Uses of Red List Data (amended by RLC) Annex 12: MoUs between IUCN and each Red List Partner (amended by IUCN and each respective Red List Partner) Annex 13: Technical and financial annual reporting template (amended by RLC) Annex 14: Guiding principles concerning timing of publication of IUCN Red List assessments on The IUCN Red List website, relative to scientific publications and press releases (amended by the RLC) * * * 16 Annex 1: Composition and Terms of Reference of the IUCN Red List Committee and its Working Groups The Red List Committee is the senior decision-making mechanism for The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. -

Critically Endangered Totoaba Totoaba Macdonaldi: Signs of Recovery and Potential Threats After a Population Collapse

Vol. 29: 1–11, 2015 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online November 4 doi: 10.3354/esr00693 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Critically Endangered totoaba Totoaba macdonaldi: signs of recovery and potential threats after a population collapse Fausto Valenzuela-Quiñonez1, Francisco Arreguín-Sánchez2, Silvia Salas-Márquez3, Francisco J. García-De León1, John C. Garza4, Martha J. Román-Rodríguez5, Juan A. De-Anda-Montañez6,* 1Catedrático CONACYT. Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas de Noroeste (CIBNOR), La Paz, B.C.S. 23096, Mexico 2Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas (CICIMAR), La Paz 23096, B.C.S. Mexico 3Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mérida, Yucatán 97310, Mexico 4Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Santa Cruz, CA 95060, USA 5Comisión de Ecología y Desarrollo Sustentable del Estado de Sonora, Jalisco 903 Col. Sonora, San Luis Colorado, Sonora C.P. 83440, Mexico 6Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas de Noroeste (CIBNOR), La Paz, B.C.S. 23096, Mexico ABSTRACT: The lack of long-term monitoring programs makes it difficult to assess signs of pop- ulation recovery in collapsed marine populations. Fishery-induced changes in the life history of exploited marine fishes, such as truncated size and age structure, local extirpations, reductions in age at maturity, and changes in mortality patterns, have occurred. In the present study, we explored life history aspects of totoaba Totoaba macdonaldi, almost 40 yr after a population col- lapse, to examine whether totoaba maintained their life history pattern and to identify the poten- tial threats of using fishing gear (hooks, gillnets). The results of the present study indicate that the totoaba size structure was not truncated as expected in overexploited populations; indeed, it was similar to that observed in the past. -

Sciaenidae 1583

click for previous page Perciformes: Percoidei: Sciaenidae 1583 SCIAENIDAE Croakers (drums) by N.L. Chao, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Brazil iagnostic characters: Small to large (5 to 200 cm), most with fairly elongate and compressed body, few Dwith high body and fins (Equetus). Head short to medium-sized, usually with bony ridges on top of skull, cavernous canals visible externally in some (Stellifer, Nebris). Eye size variable, 1/9 to 1/3 in head length, some near-shore species with smaller eyes (Lonchurus, Nebris) and those mid- to deeper water ones with larger eyes (Ctenosciaena, Odontoscion).Mouth position and size extremely variable, from large, oblique with lower jaw projecting (Cynoscion) to small, inferior (Leiostomus) or with barbels (Paralonchurus). Sen- sory pores present at tip of snout (rostral pores, 3 to 7), and on lower margin of snout (marginal pores, 2 or 5). Tip of lower jaw (chin) with 2 to 6 mental pores, some with barbels, a single barbel (Menticirrhus), or in pairs along median edges of lower jaw (Micropogonias) or subopercles (Paralonchurus, Pogonias). Teeth usually small, villiform, set in bands on jaws with outer row of upper jaw and inner row of lower jaw slightly larger (Micropogonias), or on narrow bony ridges (Bairdiella); some with a pair of large ca- nines at the tip of upper jaw (Cynoscion, Isopisthus) or series of arrowhead canines on both jaws (Macrodon); roof of mouth toothless (no teeth on prevomer or palatine bones).Preopercle usually scaled, with or with- out spines or serration on -

In the Gulf of California, Illegal Fishing for Totoaba, An

In the Gulf of California, illegal fishing for totoaba, an endangered fish whose swim bladder is prized in China for its purported medicinal properties, has forced another species, the vaquita porpoise, to the edge of extinction. 52 WILD HOPE A TALE OF TWO SPECIES BOGLE SEAN BY PHOTOGRAPH WH__Mag17_Vol3_Pgs_CC.indd 53 1/23/17 10:08 AM Wild Lens, a wildlife conservation media company, has just released the first installment of Souls of the Vermillion Sea, a documentary about the vaquita’s plight and the efforts underway to protect it. Wild Hope spoke with filmmaker Sean Bogle to find out first hand how the future looks for the vaquita. WILD HOPE: Before going into spring every other year. It’s where there are underwater It’s a sad story really be- your reasons for making a not known if that’s due to an canyons and their food is cause this region of Mexico documentary, what can you tell us imbalance in the male-to- concentrated. The totoaba are was built around the totoaba about the vaquita’s life history? female ratio. So that’s a con- there for the same reason. And fshery back in the 1920s. SEAN BOGLE: The vaquita is servation concern — we’re not that’s where the trouble lies. People moved there because the most endangered marine sure if there are enough males The fshermen fsh these can- of totoaba, which are big fsh, mammal in the world — there or females to repopulate the yons because they know the and there were plenty of them. -

Re: Mexico's New Fishing Regulations Applicable to CITES Totoaba And

Via Electronic Mail April 1, 2021 Re: Mexico’s New Fishing Regulations Applicable to CITES Totoaba and Vaquita Decisions 18.292-18.295 Dear Secretary-General Higuero, On behalf of the Animal Welfare Institute, Center for Biological Diversity, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Environmental Investigation Agency, we write to provide information regarding new fishing regulations issued by Mexico to protect vaquita and totoaba in Mexico’s northern Gulf of California and Mexico’s continued enforcement failures. As detailed below, Mexico’s new regulations, published on September 24, 20201 and supplemented in January 2021, potentially offer the vaquita and totoaba important, new protections and are a substantial improvement from previous regulations. However, key components of the regulations remain unimplemented, and illegal fishing continues—a familiar pattern, as the Mexican government has a long history of issuing but not enforcing regulations. The IUCN recently described illegal fishing as “uncontrolled,” and the Mexican government is considering shrinking the area in which gillnets are currently banned. The Mexican government has not yet demonstrated that the vaquita and totoaba are effectively protected. Mexico’s continued failure to address the ongoing fishing and trade of totoaba and ongoing critical endangerment of the vaquita violates the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Accordingly, we urge the Secretariat and Standing Committee to formally initiate compliance procedures under Resolution Conf. 14.3 and recommend sanctions against Mexico for its continued violation of CITES, to be discussed at the 73rd Standing Committee virtual meeting this spring, or no later than the Standing Committee meeting scheduled for September 2021.