Teaching the Impact of Litigation Costs on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House and Hale to Close in January Iran to Sentences for Acquin 105

28 - EVENING HERALD. Thun., Nov. M, 197» Illing Posts Honor Roll Three Leave Girl Scouts Appoint MANCHESTER - Here Brody, Raymond Brookes, Flanagan, James Fralllcciar- Palmer.. Christopher Parker, Laura School Staff is the first quarter honor Denlae Buonano, Steven dl, John Frallicciardi, Debra Several New Leaders Byam. Galligan, Gary Gates, Leonie Parliman, Laura Petersen, roli for Illing Junior High Doreen Phelps, Desiree Pina, VERNON -T h e Board of Educa Marie Campion, Michael Glaeser, Alex Glenn, Heidi MANCHESTER -The Sines, Diane Vasko, Cynthia Hen- School: Deborah Poland, Sandra tion has accepted, with regret, the Coakley, Colleen Cun Goehring. Manchester-Bolton Community niquin, Janet McCann, Judith White, G rade 7 Prior, David Ramsey. resignations of three staff members. ningham, Charles Curtiss, Timothy Graboski, Pamela Association of the Connecticut Valley Ann Brock, Susan Burbank, Shirley House and Hale To Close in January Wayne Reading, William Carrie Adams, Kathi Liane Darna, Kimberly Gurney, Mary Jo Heine, Kurt Girl Scout Council has appointed Reading. Karen Roy, Elsther Donna Frey, a Grade 5 teacher at Cyr, Wendy Palermo, Helen Zlllora, Albert, Kathleen Albert. Davis. Heinrich, Amy Huggans, a number of new leaders. They were Mary Gannon, Maureen Parker, and Saunders, Elizabeth the Maple Street School for almost 12 opened in 1853 by Edwin M. House. It it, we can’t afford to continue the The store has been conducting a 20 1960 many renovations were made to Kathleen Ambach, Thomas fXrnna DeBonee, Ashwani Kimberly Hutt, David James, given Girl Scout pins at a recent' Laura Choinski. By BARBARA RICHMOND Upstairs one side caters to women Paul Jonas Jr. -

Coca-Cola Information 10/2019

Coca-Cola Information 10/2019 20oz Plastic Bottles - $19.31 (24) 12oz Cans - $9.20 (24) Smartwater Dasani Water Coca-Cola Coca-Cola 700ml sportcap (24) - $22.72 Concessions Coca-Cola Zero Sugar Diet Coke 20oz (24) - $22.18 20oz (24) - $12.05 Diet Coke Sprite Special Events Only Sprite Sprite Zero 16.9oz Vitaminwater - $19.31 (24) 12oz (24) - $9.20 Sprite Zero Dr Pepper Power – C 16.9oz (24) – $7.58 Dr Pepper Diet Dr Pepper XXX Diet Dr Pepper Cherry Dr Pepper XXX Zero 10oz Tum E Yummie Dr Pepper 10 Diet Cherry Dr Pepper Rise Zero $9.40 (12) Cherry Dr Pepper Mello Yello Revive – Red Diet Cherry Dr Pepper Mello Yello Zero Squeezed Zero Blue Mello Yello Coke Zero Sugar Orange Mello Yello Zero Cf. Free Diet Coke Green Cf. Free Diet Coke Fanta Orange/Grape/Straw 18.5oz Gold Peak Tea - $14.46 (12) Fanta Orange Barq’s Rootbeer Sweet Barq’s Rootbeer Squirt Slightly Sweet Squirt Pink Lemonade 10oz Minute Maid Juice - Unsweet Pink Lemonade Lemonade $17.76 (24) Extra Sweet Lemonade Orange Diet Black Tea Apple Raspberry 20oz Powerade - $21.13 (24) 14oz Core Power Protein Peach Mtn. Berry Blast Drink - $31.20 Lemon Mixed Berry Zero 20g: Strawberry Bananna Lemonade Tea 15.2oz Minute Maid Juice Fruit Punch 26g: Chocolate Unsweet Lemon - $28.19 (24) Fruit Punch Zero 26g: Vanilla Unsweet Raspberry Orange Grape Green Apple Grape Zero Diet Green Tea CranGrape Strawberry Lemonade CranApple Rasp. Lemon Lime Orange 13.7oz Dunkin Donuts Drinks - 13.7oz McCafe 16oz Bodyarmor SuperDrink – 16oz Bodyarmor Lyte SuperDrink – $23.03 (12) Frappe - $23.03 (12) $18.20 (12) $18.20 (12) Original Iced Caramel Strawberry Banana Peach Mango Espresso Mocha Orange Mango Berry Punch French Vanilla Vanilla Fruit Punch Coconut Mocha Blackout Berry Orange Citrus Pumpkin Spice Pineapple Coconut Blueberry Pomegranate Cookies & Cream Tropical Punch Mixed Berry Berry Lemonade For product orders & equipment repair please call (417)865-9900. -

2010 Product List

200 Milens Road, Tonawanda, NY 14150 Phone: 716-874-4610 Fax: 716-874-7739 “Get Quenched” @ cocacolabuffalo.com 2010 PRODUCT LIST 20 oz Plastic 2 Liter Bottle Dasani Water 20 oz Glaceau Vitamin Water Coca-Cola Coca-Cola 20 oz Dasani XXX (acai-blueberry-pom) Diet Coke Diet Coke 12oz Dasani Power-C (dragon fruit) Sprite Sprite 1 Liter Dasani Revive (fruit punch) Sprite Zero Sprite Zero 20 oz Powerade Energy (tropical citrus) Cherry Coke Cherry Coke Mountain Blast Multi-V (lemonade) Cherry Zero Cherry Zero Fruit Punch Formula 50 (grape) Sunkist Orange Fanta Grape Orange Essential (orange) Sunkist Orange Diet Sunkist Diet Sunkist Strawberry Lemonade Defense (raspberry-apple) Coke Zero Coke Zero Grape Focus (kiwi-strawberry) Diet w/ lime Diet w/ lime Zero Mixed Berry Dwnld (berry-cherry) Canada Dry Ginger Ale Canada Dry Ale Zero Grape Connect (black cherry lime) Tahitian Treat Diet Canada Dry Ale 32oz Powerade Spark (grape-blueberry) Nestea Diet Cranberry Ale Mountain Blast 20 oz Vitamin Water ZERO Barqs Rootbeer Cranberry Ale Orange XXX (acai-blueberry-pom) Mello Yello - NEW! Canada Dry Green tea ale Fruit Punch Rise (orange) Caffeine Free Diet Coke Tahitian Treat Grape Squeeze (lemonade) Crystal Beach Loganberry Nestea Lemon/Lime Recoup (peach mandarin) Minute Maid Lemonade Barqs Rootbeer Sour Melon Mega- C (grape raspberry) Minute Maid Pink Lemonade Caffeine Free Coke & CF DC Strawberry Lemonade Go-Go (mixed berry) Minute Maid Fruit Punch Mello Yello Zero Strawberry Minute Maid Orangeade Crystal Beach Loganberry Zero Grape Crystal Beach -

Jional Mjl1ryofart

JIONAL MJL1RYOFART SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • REpublic 7-4215 extension 248 HOLD FOR RELEASE: MONDAY, December 2, 1964 Washington, D»C., December 2, 1964, John Walker, Director of the National Gallery of Art, announced today that a ceremony marking the first day of issue of a U.S. commemorative postage stamp honoring the fine arts will be held at 11:00 a.m. Wednesday, December 2, in the National Gallery auditorium. The stamp, based on a design by Stuart Davis, reproduces the first piece of abstract art ever to appear on a U.S. stamp. The ceremony will be open to invited guests and to the general public A temporary post office will be set up in the Gallery to post mark first day covers. The National Gallery and the main post office in Washington will be the only two locations cancelling covers on that day. The Gallery will exhibit four original prints by Stuart Davis related to the stamp design, on loan from Mrs. Edith Gregor Halpert of the Downtown Gallery, New York. Also on view will be compet1 r 5 designs, by leading artists, together with illustrations of the evolution of the stampo Speakers at the ceremony will be the Hon. John A. Gronouski, Postmaster General; Mr. Lloyd Goodrich, Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; and Mr. Harold Weston, Chairman of the United States Committee ofthe International Association of Art. Mrs. Stuart Davis, widow of the artist who died on June 24 of this year, will also attend, together with her son, 12, a stamp collector. -

MAC List for Website.Xlsx

Manufacturer Alpha Codes (MAC) in compliance with the Office Products Industry Data Standards (OPIDS) Initiative Common Name/Brand Vendor Name MAC Country 1 Shot Spraylat OSG USA 2FA 2FA Inc TFA USA 2X Software 2X Software LLC TXS USA 2XL Corp. 2XL Corp TXL USA 360 Athletics 360 Athletics AHL Canada 3D Systems 3D Systems Inc TDS USA 3K Mobel USA 3K Mobel USA KKK USA 3L Corp 3L Corp LLL USA 3M Commercial Office Sply Co 3M Commercial Office Sply Co MMM USA 3M Touch Systems 3M Touch Systems TTS USA 3ware 3ware TWR USA 3Y Power Technology 3Y Power Technology Inc TYP USA 4D Global Partners 4D Global Partners LLC FDG USA 4Kamm International 4Kamm Intl FKA USA 5-hour Energy Living Essentials LLC FHE USA 6fusion 6fusion USA Inc SFU USA 9to5 Seating 9to5 Seating NTF USA A & W Products Co Inc A & W Products Co Inc AWP USA A Deeper View A Deeper View LLC ADP USA A Toner Warehouse A Toner Warehouse ATW USA A. J. Funk and Co. AJ Funk and Co FUN USA A. W. Peller & Associates Inc A W Peller & Associates Inc EIM USA AAEON AAEON Electronics Inc AEL USA AARCO Products AARCO Products Inc AAR USA Aastra Aastra USA Inc AAS USA AAXA Technologies AAXA Technologies AAX USA ABCO Office Furniture, A Jami Co. ABCO Office Furniture ABC USA Abrams Books La Martinière (UK) Ltd ABR England Absolute Battery/PSA Parts Ltd. PSA Group ABT England Absolute Software Inc. Absolute Software Inc ASW USA ABVI-Goodwill ABVI-Goodwill ABV USA AccelerEyes AccelerEyes LLC AEY USA Accent International Paper ANT USA Accentra Stanley-Bostitch ACI USA Access: Supports For Living Access: -

Coca-Cola Beverage Agreement DATE

HABERSHAM COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SUBJECT: Coca-Cola Beverage Agreement DATE: 11/06/2019 (X) RECOMMENDATION ( ) POLICY DISCUSSION BUDGET INFORMATION: ( ) STATUS REPORT ANNUAL- ( ) OTHER CAPITAL- COMMISSION ACTION REQUESTED ON: November 18th, 2019 PURPOSE: This agreement will allow us to continue our strong partnership with Coca-Cola for up to the next five years. This agreement will renew automatically on an annual basis, up to five years, unless otherwise stated, or terminated, by either party. BACKGROUND / HISTORY: Coca-Cola products have been sold for many years within the Parks and Recreation Department. By purchasing products directly from Coca-Cola, we are eligible for discounts not available at storefronts. Coca-Cola is primarily sold at our concession window at the Ruby C. Fulbright Aquatic Center during activities and special events. Coca-Cola also provides beverage vending machines, found at park locations, managed by the bottler. We receive a percentage of all vending machine sales. FACTS AND ISSUES: By providing Coca-Cola products through our concessions, Coca-Cola will provide us with the following incentive: Sponsorship: $1,500 in sponsorship fees to be paid annually by Coca-Cola, throughout the contract period (5 years), for any recreational needs. Vending: A 20% rebate will be issued on all sales by Coca-Cola managed vending machines on site. Pricing: Discounted pricing on all Coca-Cola products (see Exhibit A) OPTIONS: 1) Approve recommendation to enter into a one-year beverage agreement with Coca-Cola Bottling Company that may annually renew for up to four successive one-year periods, for a total of five years. -

2014 Annual Review

The Coca-Cola Company 2014 Annual Review Shaping Our Future 2 Letter to Shareowners 8 Selected Financial Data 9 Let’s Get to Work 10 Our Way Forward 12 Wake Up 14 Every Day. Everywhere 16 Aim High 18 Thirsty for More 20 Prime Time 22 Coming Together 24 A New Day 26 Business Profile 27 The Coca-Cola System 28 Management 29 Board of Directors 30 Shareowner Information 3 1 Reconciliation of GAAP and Non-GAAP Financial Measures 32 Company Statements Since 1886, our associates have been defined by an ability to win the hearts and minds of those we refresh with our beverages. Today, the men and women of The Coca-Cola Company are shaping the future with a plan to drive sustainable growth and create enduring value for you. As they do, they’re inspired by the extraordinary potential of the nonalcoholic beverage industry and the promise of refreshing a growing world. Our associates are the faces you see inside this report. The Coca-Cola Company 2014 Annual Review | 1 Dear Fellow Shareowners, Tomorrow morning, about 2 billion households will wake up around the world, all of them thirsty and eager for refreshment. On average, each of these families will consume 26 drink servings throughout the day. And beverages of The Coca-Cola Company will account for about one and a half of those 26 servings. That’s just one reason we believe in our growth execute faster, and we believed we could improve potential. But we’re also keenly aware that we’re with the right changes. -

Product Manufacturer AHA BLUEBERRY POMEGRANATE 16Z

Product Manufacturer AHA BLUEBERRY POMEGRANATE 16z CN Coca-Cola AHA CITRUS GREEN TEA 16z CN Coca-Cola AHA LIME WATERMELON 16z CN Coca-Cola AHA ORANGE GRAPEFRUIT 16z CN Coca-Cola BARQS RED CRM SODA 20z NR Coca-Cola BARQS ROOT BR 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola BARQS ROOT BR 12z CN Coca-Cola BARQS ROOT BR 20z NR Coca-Cola BARQS ROOT BR CONTOUR 2L Coca-Cola CNTRY TME LMND 2LTR Coca-Cola Coca-Cola ENERGY 12z CN Coca-Cola Coca-Cola ENERGY CHERRY 12z CN Coca-Cola Coca-Cola ENERGY CHERRY ZERO SUGAR 12z CN Coca-Cola Coca-Cola ENERGY ZERO SUGAR 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE 12z NR GLS IMPORT Coca-Cola COKE 3LTR Coca-Cola COKE CALIFORNIA RASPBERRY 12z NR GLS Coca-Cola COKE CF DT 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CF DT 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CHERRY VANILLA 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHERRY VANILLA 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CHERRY VANILLA 6pk 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 1 LTR Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 24PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHRY 24z NR SINGLE Coca-Cola COKE CHRY ZERO 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CHRY ZERO 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CHRY16z CN Coca-Cola COKE CINNAMON 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CLSC .5L NR Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 15PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 16z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 1L Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 20PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 20z NR Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 24PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC 24z NR Coca-Cola COKE CLSC CF 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC DT 12PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC DT 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC DT 15PK 12z CN Coca-Cola COKE CLSC DT -

List of Exhibitions Held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art from 1897 to 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington February 14, 2018 Corcoran Gallery of Art Exhibition List 1897 – 2014 The National Gallery of Art assumed stewardship of a world-renowned collection of paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, prints, drawings, and photographs with the closing of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in late 2014. Many works from the Corcoran’s collection featured prominently in exhibitions held at that museum over its long history. To facilitate research on those and other objects included in Corcoran exhibitions, following is a list of all special exhibitions held at the Corcoran from 1897 until its closing in 2014. Exhibitions for which a catalog was produced are noted. Many catalogs may be found in the National Gallery of Art Library (nga.gov/research/library.html), the libraries at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/), or in the Corcoran Archives, now housed at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/scrc/corcoran-archives). Other materials documenting many of these exhibitions are also housed in the Corcoran Archives. Exhibition of Tapestries Belonging to Mr. Charles M. Ffoulke, of Washington, DC December 14, 1897 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. AIA Loan Exhibition April 11–28, 1898 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the Corcoran School of Art May 31–June 5, 1899 Exhibition of Paintings by the Artists of Washington, Held under the Auspices of a Committee of Ladies, of Which Mrs. John B. Henderson Was Chairman May 4–21, 1900 Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the CorCoran SChool of Art May 30–June 4, 1900 Fifth Annual Exhibition of the Washington Water Color Club November 12–December 6, 1900 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. -

Presentation: Concessions Forum, 8.24.17

Concessions August 2017 Forum 08.24.2017 1 Welcome Zenola Campbell Vice President, Concessions 2 Agenda Welcome & New Staff Introductions Air Service Development Millennial Dining Trends Grab Updates Concessionaire Food Donation Program Coca-Cola Updates BDD Compliance Technology Security Airport Safety and Security Docks and Storage & Terminal C Updates Hiring Recruitment and Janitorial Survey Award Criteria / Clean Working Friendly Questions and Closing 3 United Way Golf Tournament Date: Wednesday, October 11, 2017 Platinum Sponsor - $15,000 Gold Sponsor - $10,000 Breakfast Sponsor - $8,000 Lunch Sponsor - $8,000 Apparel Sponsor - $8,000 Merchandise Sponsor - $8,000 Beverage Cart Sponsor - $8,000 Photo Sponsor - $8,000 Team Sponsor - $2,500 4 Air Service Matt Whitehead Airline Relations and Analytics Manager 5 DFW Air Service Highlights Global Strategy & Development 6 DFW enplanements projected to hit record high in FY 2017 DFW Enplanements (in Millions) 35 +1.2% YOY 33 33.3 32.5 32.9 31 31.4 30.6 29 29.9 30.1 29.1 28.9 29.1 27 27.9 28.2 25 23 FY 00 FY 07 FY 08 FY 09 FY 10 FY 11 FY 12 FY 13 FY 14 FY 15 FY 16 FY 17 CAGR represents Compound Annual Growth Rate Source: DFW Monthly Flight Activity Reports, GSD Forecast 7 International enplanements has grown tremendously in the last 5 years DFW International Enplanements (in Millions) 5 +6.4% Y/Y 4 4.4 4.1 3.9 3.5 3 3.3 2.8 3.0 2 1 0 FY 11 FY 12 FY 13 FY 14 FY 15 FY16 FY 17 CAGR represents Compound Annual Growth Rate Source: DFW Monthly Flight Activity Reports, GSD Forecast 8 FY 2017 International Passengers International passenger traffic was up across most regions. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

This page intentionally left blank This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 This page intentionally left blank A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 2 Painters born from 1850 to 1910 by Dorothy W. Phillips Curator of Collections The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.G. 1973 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number N 850. A 617 Designed by Graham Johnson/Lund Humphries Printed in Great Britain by Lund Humphries Contents Foreword by Roy Slade, Director vi Introduction by Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., Director Emeritus vii Acknowledgments ix Notes on the Catalogue x Catalogue i Index of titles and artists 199 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As Director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, I am pleased that Volume II of the Catalogue of the American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art, which has been in preparation for some five years, has come to fruition in my tenure. The second volume deals with the paintings of artists born between 1850 and 1910. The documented catalogue of the Corcoran's American paintings carries forward the project, initiated by former Director Hermann Warner Williams, Jr., of providing a series of defini• tive publications of the Gallery's considerable collection of American art. The Gallery intends to continue with other volumes devoted to contemporary American painting, sculpture, drawings, watercolors and prints. In recent years the growing interest in and concern for American paint• ing has become apparent. -

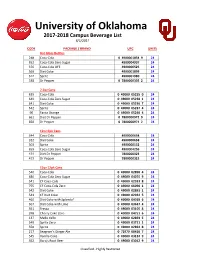

2 Oklahoma University Campus Beverage List 8.1.2017.Xlsx

University of Oklahoma 2017‐2018 Campus Beverage List 8/1/2017 CODE PACKAGE / BRAND UPC UNITS 8oz Glass Bottles 248 Coca‐Cola 0 4900001834 9 24 652 Coca‐Cola Zero Sugar 4900004997 24 376 Coca‐Cola LIFE 4900006525 24 569 Diet Coke 4900001899 24 612 Sprite 4900001980 24 538 Dr Pepper 0 7800000335 2 24 7.5oz Cans 635 Coca‐Cola 0 49000 05235 0 24 640 Coca‐Cola Zero Sugar 0 49000 05238 1 24 641 Diet Coke 0 49000 05236 7 24 642 Sprite 0 49000 05237 4 24 90 Fanta Orange 0 49000 05240 4 24 661 Diet Dr Pepper 0 7800000972 9 24 660 Dr Pepper 0 7800000971 2 24 12oz 6pk Cans 344 Coca‐Cola 4900000634 24 322 Diet Coke 4900000658 24 303 Sprite 4900000132 24 659 Coca‐Cola Zero Sugar 4900004256 24 474 Diet Dr Pepper 7800000323 24 473 Dr Pepper 7800000315 24 12oz 12pk Cans 540 Coca‐Cola 0 49000 02890 4 24 686 Coca‐Cola Zero Sugar 0 49000 04255 9 24 541 CF Coca‐Cola 0 49000 02933 8 24 755 CF Coca‐Cola Zero 0 49000 06090 1 24 542 Diet Coke 0 49000 02891 1 24 543 CF Diet Coke 0 49000 02934 5 24 460 Diet Coke with Splenda* 0 49000 04269 6 24 667 Diet Coke with Lime 0 49000 03637 4 24 551 Fresca 0 49000 03105 8 24 398 Cherry Coke Zero 0 49000 04751 6 24 137 Mello Yello 0 49000 02893 5 24 549 Sprite Zero 0 49000 03711 1 24 550 Sprite 0 49000 02892 8 24 217 Seagram's Ginger Ale 0 72979 00416 7 24 545 Vanilla Coke 0 49000 03124 9 24 552 Barq's Root Beer 0 49000 03012 9 24 Classified ‐ Highly Restricted University of Oklahoma 2017‐2018 Campus Beverage List 8/1/2017 CODE PACKAGE / BRAND UPC UNITS 547 Cherry Coke 0 49000 03103 4 24 558 Minute Maid Lemonade 0 25000