Zenger 1991.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

2005 Annual Report

RESULTS Matter 2005 Annual Report The E.W. Scripps Company Mission The E.W.The Company Scripps 2005 Annual Report The E.W. Scripps Company strives for excellence in the products and services we produce and responsible service to the communities in which we operate. Our purpose is to continue to engage in successful, growing enterprises in the fields of information and entertainment. The company intends to expand, develop and acquire new products and services, and to pursue new market opportunities. Our focus shall be long-term growth for the benefit of shareholders and employees. P.O. Box 5380 Cincinnati, Ohio 45201 www.scripps.com The E. W. Scripps Company 2005 Annual Report Board of Directors RESULTS do matter and they’re what The E.W. Scripps 123456 Company is all about. Millions of engaged media consumers, and the advertisers and merchants who want to reach them, turn to 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scripps every day for a growing range of innovative information services that excel at delivering outstanding results. 1 William R. Burleigh, 70 3 Paul K. Scripps, 60 6 David A. Galloway, 62 8 Ronald W. Tysoe, 52 11 Jarl Mohn, 54 Chairman of the company since May 1999 and Chairman Retired Vice President/ Corporate Director; Vice Chairman, Trustee, Mohn of the Executive Committee since October 2000. He joined Newspapers, The E.W. retired President and Federated Department Family Trust; retired the Board of Directors in 1990. He served as President and Scripps Company. CEO, Torstar Corp. Stores Inc. Director President & Chief Chief Executive Officer from May 1996 until September 2000 Director since 1986. -

The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns's

Interfaces Image Texte Language 41 | 2019 Images / Memories The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series Camille Rouquet Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.647 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 21 June 2019 Number of pages: 65-83 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Camille Rouquet, “The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series”, Interfaces [Online], 41 | 2019, Online since 21 June 2019, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.647 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. THE LEGACY OF AMERICAN PHOTOJOURNALISM IN KEN BURNS’S VIETNAM WAR DOCUMENTARY SERIES Camille Rouquet LARCA/Paris Sciences et Lettres In his review of The Vietnam War, the 18-hour-long documentary series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick released in September 2017, New York Times television critic James Poniewozik wrote: “The Vietnam War” is not Mr. Burns’s most innovative film. Since the war was waged in the TV era, the filmmakers rely less exclusively on the trademark “Ken Burns effect” pans over still images. Since Vietnam was the “living-room war,” played out on the nightly news, this documentary doesn’t show us the fighting with new eyes, the way “The War” did with its unearthed archival World War II footage. -

Aa000343.Pdf (12.91Mb)

COMFORT SHOE New Style! New Comfort! Haband’s LOW 99 PRICE: per pair 29Roomy new box toe and all the Dr. Scholl’s wonderful comfort your feet are used to, now with handsome new “D-Ring” MagicCling™ closure that is so easy to “touch and go.” Soft supple uppers are genuine leather with durable man-made counter, quarter & trim. Easy-on Fully padded foam-backed linings Easy-off throughout, even on collar, tongue & Magic Cling™ strap, cradle & cushion your feet. strap! Get comfort you can count on, with no buckles, laces or ties, just one simple flick of the MagicCling™ strap and you’re set! Order now! Tan Duke Habernickel, Pres. 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Peckville, PA 18452 White Black Medium & Wide Widths! per pair ORDER 99 Brown FREE Postage! HERE! Imported Walking Shoes 292 for 55.40 3 for 80.75 Haband 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. 1 1 D Widths: 77⁄2 88⁄2 9 Molded heel cup Peckville, Pennsylvania 18452 1 1 NEW! 9 ⁄2 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 with latex pad COMFORT INSOLE Send ____ shoes. I enclose $_______ EEE Widths: positions foot and 1 1 purchase price plus $6.95 toward 88⁄2 9 9 ⁄2 Perforated sock and insole 1 adds extra layer 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 for breathability, postage. of cushioning GA residents FREE POSTAGE! NO EXTRA CHARGE for EEE! flexibility & add sales tax EVA heel insert for comfort 7TY–46102 WHAT WHAT HOW shock-absorption Check SIZE? WIDTH? MANY? 02 TAN TPR outsole 09 WHITE for lightweight 04 BROWN comfort 01 BLACK ® Modular System Card # _________________________________________Exp.: ______/_____ for cushioned comfort Mr./Mrs./Ms._____________________________________________________ ©2004 Schering-Plough HealthCare Products, Inc. -

Workbook 7.Indd

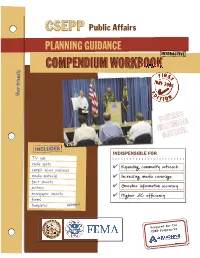

CSEPPCSEPP Public Affairs PLANNING GUIDANCE COMPENDIUM WORKBOOK CONTAINS MULTIMEDIA MATERIAL INCLUDES INDISPENSIBLE FOR TV ads radio spots Expanding community outreach sample news releases media material Increasing media coverage fact sheets posters Greater information accuracy newspaper inserts Higher JIC efficiency forms re! templates and mo for the Prepared ram by CSEP Prog 2 ☞ Instructions Th is Workbook CD contains the following elements. Th ere are no hyperlinks between them. Main document PDF fi le (what you are reading now). Th ere are also three kinds of supporting documents on the CD. Th ey are listed in the text with their titles in blue italics. On the CD, they are organized within folders that are named and numbered to correspond to the sections of this main document. Supporting documents in PDF format. Th ey can be opened with Acrobat Reader (a free download from www.adobe.com). If you are reading this, Reader is already installed on your computer. Th ese documents are QuickTime multimedia fi les — audio for the radio spots and audio+video for the television spots. You must have QuickTime installed on your computer to see and/or hear these fi les. QuickTime is a free download from www.apple.com. Make sure your speakers are connected and your computer’s sound is turned on. Microsoft Word fi les. Th ey can be opened in Word and used as modifi able templates. PowerPoint presentation. Graphics fi les are provided in these formats, in addition to PDF. Th ese can be imported into art editing and page layout programs. Th e icons indicate, left to right, Adobe Illustrator, Encapsulated PostScript, Joint Experts Photographic Group (also known as JPEG, a standard format for use on the Web), and Tagged Image Format. -

NEEDLESS DEATHS in the GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During The

NEEDLESS DEATHS IN THE GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 November 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover design by Patti Lacobee Watch Committee Middle East Watch was established in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry is the associate director; Aziz Abu Hamad is the senior researcher; John V. White is an Orville Schell Fellow; and Christina Derry is the associate. Needless deaths in the Gulf War: civilian casualties during the air campaign and violations of the laws of war. p. cm -- (A Middle East Watch report) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56432-029-4 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991--United States. 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991-- Atrocities. 3. War victims--Iraq. 4. War--Protection of civilians. I. Human Rights Watch (Organization) II. Series. DS79.72.N44 1991 956.704'3--dc20 91-37902 CIP Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. The executive committee comprises Robert L. Bernstein, chair; Adrian DeWind, vice chair; Roland Algrant, Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan Fanton, Jack Greenberg, Alice H. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 6.0 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT .................................................................................. 6-1 6.1 Objectives...........................................................................................................6-1 6.2 Elements of Program..........................................................................................6-1 6.3 Agency Input ......................................................................................................6-6 6.4 Public Input.......................................................................................................6-11 6.5 Special Outreach to Low-Income and Minority Populations.............................6-20 6.6 Release of Draft EIS.........................................................................................6-25 6.7 Coordination Subsequent to Release of Final EIS ...........................................6-26 TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 6-1 Mailing Distribution Area.....................................................................................6-3 LIST OF TABLES Page Table 6-1 Local Media Contact List ....................................................................................6-5 Table 6-2 Agency and Local Government Involvement Activities.......................................6-7 Table 6-3 Summary of Citizen Working Group Meetings .................................................6-13 Table 6-4 Local Neighborhood Associations and Business Groups.................................6-15 Table 6-5 -

Unquiet American: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65

THE UNQUIET AMERICAN: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65 The Unquiet American: Malcolm Browne in Saigon, 1961–65, other invidious means to impede reporting he perceived Browne’s photograph of the self-immolation of Thich an exhibit drawn from The Associated Press Corporate as critical of his government. Meanwhile, the White House Quan Duc, taken on June 11, 1963, led President John F. From left: Archives, honors the courageous journalism of Malcolm and Pentagon provided little information to reporters and Kennedy to reappraise U.S. support of Diem. After Diem’s Malcolm Browne at work in New York as a chemist for the Foster D. Snell Browne (1931–2012) during the early years of the Vietnam pressured them for favorable coverage of both the political murder on Nov. 1, 1963, in a coup that most probably had Co. in 1953, before his induction into the military and subsequent career War. While Browne was reporting a war being run largely and military situations. the administration’s tacit approval, Browne provided an in journalism. covertly by the White House, the CIA and the Pentagon, unmatched account of Diem’s final hours that received PHOTO COURTESY LE LIEU BROWNE he was waging his own battles in another: the war against Browne arrived in Saigon on Nov. 7, 1961, joining Vietnamese tremendous play. For his breaking news stories and his Associated Press General Manager Wes Gallagher, left, walks with AP journalists. Meanwhile, he accompanied U.S. advisers colleague Ha Van Tran. The bureau soon acquired two astute analysis of a war in the making, Browne won the correspondent Malcolm Browne in Saigon upon Gallagher’s arrival, March 20, by helicopter into the countryside seeking the latest formidable additions, correspondent Peter Arnett and Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 1964. -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

Media Images of War 3(1) 7–41 © the Author(S) 2010 Reprints and Permission: Sagepub

MWC Article Media, War & Conflict Media images of war 3(1) 7–41 © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub. co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1750635210356813 Michael Griffin http://mwc.sagepub.com Macalester College, Saint Paul, MN, USA Abstract Photographic images of war have been used to accentuate and lend authority to war reporting since the early 20th century, with depictions in 1930s picture magazines of the Spanish Civil War prompting unprecedented expectations for frontline visual coverage. By the 1960s, Vietnam War coverage came to be associated with personal, independent and uncensored reporting and image making, seen as a journalistic ideal by some, and an obstacle to successful government conduct of the war by others. This article considers the idealized ‘myth’ of Vietnam War coverage and how it has influenced print and television photojournalism of American conflicts, skewing expectations of wartime media performance and fostering a consistent pattern of US Government/media collaboration. Upon analysis, pictorial coverage of US wars by the American media not only fails to live up to the myth of Vietnam but tends to be compliant and nationalist. It fails to reflect popular ideals of independent and critical photojournalism, or even the willingness to depict the realities of war. Keywords documentary, Gulf War, Iraq War, journalism, news, photography, photojournalism, television, television news, Vietnam War, visual communication, visual culture, war, war photography Media representations of war are of interest to media scholars for many reasons. First, as reports or images associated with extreme conflict and matters of life and death, they tend to draw intense public attention, and potentially influence public opinion. -

A TIMELINE for GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003)

A TIMELINE FOR GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003) "When a society or a civilization perishes, one condition can always be found. They forgot where they came from." Carl Sandburg This time-line was originally created by the Golden Historic Preservation Board for the 1995 Golden community meetings concerning growth. It is intended to illustrate some of the events and thoughts that helped shape Golden. Major historical events and common day-to-day happenings that influenced the lives of the people of Golden are included. Corrections, additions, and suggestions are welcome and may be relayed to either the Historic Preservation Board or the Planning Department at 384-8097. The information concerning events in Golden was gathered from a variety of sources. Among those used were: • The Colorado Transcript • The Golden Transcript • The Rocky Mountain News • The Denver Post State of Colorado Web pages, in particular the Colorado State Archives The League of Women Voters annual reports Golden, The 19th Century: A Colorado Chronicle. Lorraine Wagenbach and Jo Ann Thistlewood. Harbinger House, Littleton, 1987 The Shining Mountains. Georgina Brown. B & B Printers, Gunnison. 1976 The 1989 Survey of Historic Buildings in Downtown Golden. R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Survey of Golden Historic Buildings. by R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Golden Survey of Historic Buildings, 1991. R. Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons. Front Range Research Associates, Inc. -

Famous Journalist Research Project

Famous Journalist Research Project Name:____________________________ The Assignment: You will research a famous journalist and present to the class your findings. You will introduce the journalist, describe his/her major accomplishments, why he/she is famous, how he/she got his/her start in journalism, pertinent personal information, and be able answer any questions from the journalism class. You should make yourself an "expert" on this person. You should know more about the person than you actually present. You will need to gather your information from a wide variety of sources: Internet, TV, magazines, newspapers, etc. You must include a list of all sources you consult. For modern day journalists, you MUST read/watch something they have done. (ie. If you were presenting on Barbara Walters, then you must actually watch at least one interview/story she has done, or a portion of one, if an entire story isn't available. If you choose a writer, then you must read at least ONE article written by that person.) Source Ideas: Biography.com, ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CNN or any news websites. NO WIKIPEDIA! The Presentation: You may be as creative as you wish to be. You may use note cards or you may memorize your presentation. You must have at least ONE visual!! Any visual must include information as well as be creative. Some possibilities include dressing as the character (if they have a distinctive way of dressing) & performing in first person (imitating the journalist), creating a video, PowerPoint or make a poster of the journalist’s life, a photo album, a smore, or something else! The main idea: Be creative as well as informative.