War and Trade: Siamese Interventions in Cambodia, 1767-1851

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Title: Rocket Festival in Transition: Rethinking 'Bun Bangfai

1 Paper Title: Rocket Festival in Transition: Rethinking ‘Bun Bangfai’ in Isan Name of Author: Pinwadee Srisupun Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology, Khon Kaen University, Thailand Advisor: Dr. Yaowaluk Apichartwallob Assoc.Prof., Khon Kaen University, Thailand Address & Contact details: Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchathani University, Ubon Ratchathani 34190 Thailand Tel: + 66 45 353 725 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Panel prefer to presentation: Socio – Cultural Transformation Abstract Every year from May to June, ethnic Lao from Laos and Northeastern Thailand hold a rocket festival called Bun Bangfai. Traditionally, rockets were launched in the festival to ask the gods, Phaya Thaen and the Naga, to produce rain in the human world for rice farming and as a blessing for happiness. The ritual combines fertility rites which are important to the agrarian society with the Buddhist concept of making merit. There is no precise history of the festival, but some believe that it originated in Tai or Dai culture in China’s Yunnan Province. The province of Yasothon in Thailand is very popular for tourists who seek traditional culture. We can see the changing of Bun Bangfai from the past to present which includes pattern, ideas, and level of arrangement and from the original ritual to some unrelated ones. This paper presents a preliminary study about Bun Bung Fai in Isan focusing on Yasothon Province of Thailand case, not only because it is well known, but it is also an international festival clearly showing the process of commodification. How can we deal with Bun Bangfai festival of Yasothon especially the commodification process from local to global level? And from this festival, how can we interpret and understand Isan people’s way of life? The study found that the festival was full of capitalists, local and international who engage in every site. -

Thailand's First Provincial Elections Since the 2014 Military Coup

ISSUE: 2021 No. 24 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 5 March 2021 Thailand’s First Provincial Elections since the 2014 Military Coup: What Has Changed and Not Changed Punchada Sirivunnabood* Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, founder of the now-dissolved Future Forward Party, attends a press conference in Bangkok on January 21, 2021, after he was accused of contravening Thailand's strict royal defamation lese majeste laws. In December 2020, the Progressive Movement competed for the post of provincial administrative organisations (PAO) chairman in 42 provinces and ran more than 1,000 candidates for PAO councils in 52 of Thailand’s 76 provinces. Although Thanathorn was banned from politics for 10 years, he involved himself in the campaign through the Progressive Movement. Photo: Lillian SUWANRUMPHA, AFP. * Punchada Sirivunnabood is Associate Professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities of Mahidol University and Visiting Fellow in the Thailand Studies Programme of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2021 No. 24 ISSN 2335-6677 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On 20 December 2020, voters across Thailand, except in Bangkok, elected representatives to provincial administrative organisations (PAO), in the first twinkle of hope for decentralisation in the past six years. • In previous sub-national elections, political parties chose to separate themselves from PAO candidates in order to balance their power among party allies who might want to contest for the same local positions. • In 2020, however, several political parties, including the Phuea Thai Party, the Democrat Party and the Progressive Movement (the successor of the Future Forward Party) officially supported PAO candidates. -

131299 Bangperng 2020 E.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 13, Issue 12, 2020 Champasak: Dhammayuttika Nikaya and the Maintenance of Power of the Thai State (Buddhist Decade 2390- 2450) Kiattisak Bangpernga, aDepartment of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Mahasarakham University, Email: [email protected] This article is intended to analyse the time during Siam's reign in Champasak, when Siam exercised the colonial power to collect tributes and taxes, resulting in the local Lao’s burdens. This caused rebels to be formed under the culture of local Buddhists combined with indigenous beliefs. Siam therefore attempted to connect the local Lao and culture to the central power. One of the important policies was to send Thammayut monks to remove the local beliefs and to disseminate pure Buddhism, according to Thai Dhammayuttika Nikaya. Later, French colonies wanted to rule the Lao territory in the name of Indochina, resulting in that the monks of Dhammayuttika Nikaya were drawn to be part of the political mechanism, in order to cultivate loyalty in the Siamese elites and spread the Thai ideology. This aimed to separate Laos from the French’s claiming of legitimacy for a colonial rule. However, even if the Dhammayuttika Nikaya was accepted and supported by the Lao rulers, but it was not generally accepted by the local people, because it was the symbol of the power of Siam who oppressed them, and appeared to have ideological differences with their local culture. Dhammayuttika Nikaya, as a state mechanism, was not successful in maintaining the power of the Thai state. -

An Integrated Land Use and Water Plan for Mahasarakham Province, Thailand

An Integrated Land Use and Water Plan for Mahasarakham Province, Thailand A thesis submitted to the School of Planning of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning in the School of Planning of the School of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2013 by Yuwadee Ongkosit B.A. Geography, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Committee Chair: David Edelman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Christopher Auffrey, Ph.D. Abstract This thesis identifies water-related problems that Mahasarakham Province, Thailand faces and the correlation between water and land use. Natural hazards are inevitable, and they ruin properties and cause changes to natural features. Two ways that the Thai government acts to mitigate their impact is to create or implement both structural and non-structural plans, but it heavily focuses on the first. The structural measures do not always relieve water-related problems. However, the non-structural measures can at least mitigate the effects posed on water resources. Land use and water resources are interconnected. One cannot separate one from another. Thus, this thesis also proposes an integrated water and land use plan that regulates the patterns of land use and prohibit certain uses at the national and local level. The proposed plan will help people better understand the interaction of land use and water resources. บทคัดย่อ วิทยานิพนธ์ฉบับนี้ ระบุปัญหาเกี่ยวกบนํั ้า ซึ่งจังหวัดมหาสารคาม ประเทศไทยประสบ รวมทั้งความสัมพันธ์ระหวางนํ่ ้าและการใช้ที่ดิน ภัยพิบัติทาง -

The Exodus of Young Labor in Yasothon Province, Thailand

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 33, No.4, March 1996 Farming by the Older Generation: The Exodus of Young Labor in Yasothon Province, Thailand Kazuo FUNAHASHI * I Introduction Thailand has undergone rapid economic development in recent years, due in large part to the remarkable development of the industrial sector in and around Bangkok. This rapid economic development has given rise to a massive exodus of people from the countryside to the cities, unlike earlier migrations, which were between rural areas. The rural areas of Northeast Thailand that are the focus of this study are no exception to this.ll This paper looks broadly at the migration of labor in Yasothon Province in the Isan region of Northeast Thailand, and the attendant changes in agriculture and rural areas in that region. One feature of the methodology of this study is that, unlike many earlier studies, it does not focus on just one village. Surveys were conducted in 97 villages randomly 2 selected at the district (amphoe) level across the whole of Yasothon Province. ) Consequently, the phenomena discussed here can be taken as indicative of province-wide trends. * fttmffJ7(, Faculty of Home Economics, Kyoto Women's University, 35 Kitahiyoshi-cho, Imakumano, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto 605 1) As has been pointed out by Hayao Fukui [1995], Hiroshi Tsujii [1982J, Machiko Watanabe [1988J, Akira Suehiro and Yasushi Yasuda [1987J, surplus labor in the rural areas in the 1950s, and even during the rapid industrialization of the 1960s, was absorbed basically by the expansion of cultivated area through migration to rural areas (mass migration of peasants to open upland fields in the mountain forests). -

4. Counter-Memorial of the Royal Government of Thailand

4. COUNTER-MEMORIAL OF THE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF THAILAND I. The present dispute concerns the sovereignty over a portion of land on which the temple of Phra Viharn stands. ("PhraViharn", which is the Thai spelling of the name, is used throughout this pleading. "Preah Vihear" is the Cambodian spelling.) 2. According to the Application (par. I), ThaiIand has, since 1949, persisted in the occupation of a portion of Cambodian territory. This accusation is quite unjustified. As will be abundantly demon- strated in the follo~vingpages, the territory in question was Siamese before the Treaty of 1904,was Ieft to Siam by the Treaty and has continued to be considered and treated as such by Thailand without any protest on the part of France or Cambodia until 1949. 3. The Government of Cambodia alleges that its "right can be established from three points of rieivJ' (Application, par. 2). The first of these is said to be "the terms of the international conventions delimiting the frontier between Cambodia and Thailand". More particuIarly, Cambodia has stated in its Application (par. 4, p. 7) that a Treaty of 13th February, 1904 ". is fundamental for the purposes of the settlement of the present dispute". The Government of Thailand agrees that this Treaty is fundamental. It is therefore common ground between the parties that the basic issue before the Court is the appIication or interpretation of that Treaty. It defines the boundary in the area of the temple as the watershed in the Dangrek mountains. The true effect of the Treaty, as will be demonstratcd later, is to put the temple on the Thai side of the frontier. -

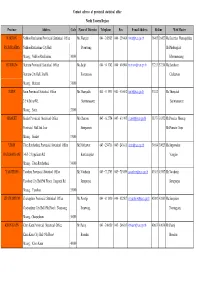

Province Address Code Name of Director Telephone Fax E-Mail

Contact adrress of provincial statistical office North Eastern Region Province Address Code Name of Director Telephone Fax E-mail AddressHotline Web Master NAKHON Nakhon Ratchasima Provincial Statistical Office Ms.Wanpen 044 - 242985 044 - 256406 [email protected] 36465 36427 Ms.Kanittha Wannapakdee RATCHASIMA Nakhon Ratchasima City Hall Poonwong Mr.Phadungkiat Muang , Nakhon Ratchasima 30000 Khmmamuang BURIRUM Burirum Provincial Statistical Office Ms.Saijit 044 - 611742 044 - 614904 [email protected] 37213 37214 Ms.Somboon Burirum City Hall, Jira Rd. Kootaranon Chaleewan Muang , Burirum 31000 SURIN Surin Provincial Statistical Office Ms.Thanyalak 044 - 511931 044 - 516062 [email protected] 37812 Ms.Thanyalak 2/5-6 Sirirat Rd. Surintarasaree Surintarasaree Muang , Surin 32000 SISAKET Sisaket Provincial Statistical Office Mr.Charoon 045 - 612754 045 - 611995 [email protected] 38373 38352 Mr.Preecha Meesup Provincial Hall 2nd floor Siengsanan Mr.Pramote Sopa Muang , Sisaket 33000 UBON Ubon Ratchathani Provincial Statistical Office Mr.Natthawat 045 - 254718 045 - 243811 [email protected] 39014 39023 Ms.Supawadee RATCHATHANI 146/1-2 Uppalisarn Rd. Kanthanaphat Vonglao Muang , Ubon Ratchathani 34000 YASOTHON Yasothon Provincial Statistical Office Mr.Vatcharin 045 - 712703 045 - 713059 [email protected] 43563 43567 Mr.Vatcharin Yasothon City Hall(5th Floor), Jangsanit Rd. Jermprapai Jermprapai Muang , Yasothon 35000 CHAIYAPHUM Chaiyaphum Provincial Statistical Office Ms.Porntip 044 - 811810 044 - 822507 [email protected] 42982 42983 Ms.Sanyakorn -

Rural Poverty and Diversification of Farming Systems in Upper Northeast Thailand Cécile Barnaud, Guy Trebuil, Marc Dufumier, Nongluck Suphanchaimart

Rural poverty and diversification of farming systems in upper northeast Thailand Cécile Barnaud, Guy Trebuil, Marc Dufumier, Nongluck Suphanchaimart To cite this version: Cécile Barnaud, Guy Trebuil, Marc Dufumier, Nongluck Suphanchaimart. Rural poverty and diversi- fication of farming systems in upper northeast Thailand. Moussons : recherches en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est, Presses universitaires de Provence, 2006, 9-10, pp.157-187. hal-00609626 HAL Id: hal-00609626 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00609626 Submitted on 19 Jul 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RURAL POVERTY AND DIVERSIFICATION OF FARMING SYSTEMS IN UPPER NORTHEAST THAILAND. 1 2 3 4 C. BARNAUD ,G.TREBUIL ,M.DUFUMIER ,N.SUPHANCHAIMART ABSTRACT In northeast Thailand, 85% of the farmers are smallholders who are unable to meet their basic needs from agricultural production only. These tiny farms survive thanks to non-farm income which face increased difficulties as other economic sectors ran out of steam during the recent economic crisis of the late 1990s. In this context, farmers have to rely more on their agricultural production activity and income. But how can this be made possible in a region well-known for its very constraining soil and climatic conditions? To answer this question, and to examine the whole complexity of agricultural development issues, this article proposes an analysis of recent agrarian transformations and an understanding of farmers’ current practices and strategies. -

Empowering a Sustainable City Using Self-Assessment of Environmental Performance on Ecocitopia Platform

sustainability Article Empowering a Sustainable City Using Self-Assessment of Environmental Performance on EcoCitOpia Platform Ratchayuda Kongboon 1, Shabbir H. Gheewala 2,3 and Sate Sampattagul 4,5,* 1 Research Unit for Energy, Economic and Ecological Management, Science and Technology Research Institute, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand; [email protected] 2 The Joint Graduate School of Energy and Environment (JGSEE), King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok 10140, Thailand; [email protected] 3 Center of Excellence on Energy Technology and Environment, PERDO, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, Bangkok 10140, Thailand 4 Department of Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 5 Excellence Center in Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In Thailand, many municipalities lack the information to guide decision-making for improving environmental performance. They need tools to systematize the collection and analysis of data, and then to self-assess environmental performance to increase efficiency in environmental management toward a sustainable city. The aim of this study is to develop a platform for self- assessment of an environmental performance index. Nonthaburi municipality, Hat Yai municipality, and Yasothon municipality were selected to study the work context for six indicators, viz., energy, greenhouse gas, water, air, waste, and green area, which were important environmental problems. Citation: Kongboon, R.; The development of an online system called “EcoCitOpia” divides municipality assessment into Gheewala, S.H.; Sampattagul, S. Empowering a Sustainable City four parts: data collection, database creation, data analysis, and data display. -

Pre-Angkorian Communities in the Middle Mekong Valley (Laos and Adjacent Areas) Michel Lorrillard

Pre-Angkorian Communities in the Middle Mekong Valley (Laos and Adjacent Areas) Michel Lorrillard To cite this version: Michel Lorrillard. Pre-Angkorian Communities in the Middle Mekong Valley (Laos and Adjacent Areas). Nicolas Revire. Before Siam: Essays in Art and Archaeology, River Books, pp.186-215, 2014, 9786167339412. halshs-02371683 HAL Id: halshs-02371683 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02371683 Submitted on 20 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. hek Thak Thakhek Nakhon Nakhon Phanom Phanom Pre-Angkorian Communities in g Fai g g Fai n n the Middle Mekong Valley Se Ba Se Se Ba Se Noi Se Se Noi (Laos and Adjacent Areas) That That That Phanom Phanom MICHEL LORRILLARD Laos Laos on on P P Vietnam Se Se Vietnam i i n n het Savannak Savannakhet Se Xang Xo Xang Se Se Xang Xo Introduction Se Champho Se Se Champho Se Bang Hieng Bang Se Se Bang Hieng he earliest forms of “Indianisation” in Laos have not been the Mekong Mekong Se Tha Moak Tha Se Se Tha Moak Tsubject of much research to date. Henri Parmentier (1927: 231, 233-235), when introducing some two hundred sites related to Se Bang Hieng Bang Se Se Bang Hieng “Khmer primitive art” – soon reclassified as “pre-Angkorian art” as being prior to the ninth century – took into account only five such sites located upstream of the Khone falls. -

05 Chalong 111-28 111 2/25/04, 1:54 PM CHALONG SOONTRAVANICH

CONTESTING VISIONS OF THE LAO PAST i 00 Prelims i-xxix 1 2/25/04, 4:48 PM NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS Studies in Asian Topics 15. Renegotiating Local Values Merete Lie and Ragnhild Lund 16. Leadership on Java Hans Antlöv and Sven Cederroth (eds) 17. Vietnam in a Changing World Irene Nørlund, Carolyn Gates and Vu Cao Dam (eds) 18. Asian Perceptions of Nature Ole Bruun and Arne Kalland (eds) 19. Imperial Policy and Southeast Asian Nationalism Hans Antlöv and Stein Tønnesson (eds) 20. The Village Concept in the Transformation of Rural Southeast Asia Mason C. Hoadley and Christer Gunnarsson (eds) 21. Identity in Asian Literature Lisbeth Littrup (ed.) 22. Mongolia in Transition Ole Bruun and Ole Odgaard (eds) 23. Asian Forms of the Nation Stein Tønnesson and Hans Antlöv (eds) 24. The Eternal Storyteller Vibeke Børdahl (ed.) 25. Japanese Influences and Presences in Asia Marie Söderberg and Ian Reader (eds) 26. Muslim Diversity Leif Manger (ed.) 27. Women and Households in Indonesia Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg and Ratna Saptari (eds) 28. The House in Southeast Asia Stephen Sparkes and Signe Howell (eds) 29. Rethinking Development in East Asia Pietro P. Masina (ed.) 30. Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia Lenore Manderson and Pranee Liamputtong (eds) 31. Imperial Japan and National Identities in Asia, 1895–1945 Li Narangoa and Robert Cribb (eds) 32. Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher E. Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) ii 00 Prelims i-xxix 2 2/25/04, 4:48 PM CONTESTING VISIONS OF THE LAO PAST LAO HISTORIOGRAPHY AT THE CROSSROADS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER E. -

Thailand's Inequality: Myths & Reality of Isan

1 THAILAND’S INEQUALITY: MYTHS & REALITY OF ISAN 2 3 THAILAND’S INEQUALITY: MYTHS & REALITY OF ISAN AUTHORS Rattana Lao omas I. Parks Charn Sangvirojkul Aram Lek-Uthai Atipong Pathanasethpong Pii Arporniem annaporn Takkhin Kroekkiat Tiamsai May 2019 Copyright © 2019 e Asia Foundation 4 5I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS is report on contemporary life in Isan, ailand’s Northeast Region, was produced with the support of a great many people. e study was co-funded by the United Kingdom and the Asia Foundation. e research team wishes to thank omas Parks, the Foundation’s Country Representative in ailand, for providing vision and encouragement through all stages of the study, including formulation of the methodology, analysis of the ndings, and drawing conclusions for this report. Important contributors during the early stages of the study were Sasiwan Chingchit, Patrick Barron, and Adrian Morel; and throughout the process, the Foundation’s sta in ailand provided crucial administrative and moral support. Most grateful thanks go to the farmers, students, and academics in Isan who participated in the survey, focus groups, and interviews, and generously provid- ed their time and valuable insights. We beneted too from the intellectual support of faculty at Khon Kaen University, Mahasarakam University, and Ubonratchathani University, and especially thank Dr. Rina Patramanon, Dr. Orathai Piayura, Dr. John Draper, Dr. Nattakarn Akarapongpisak, Dr. Titipol Phakdeewanich, and Dr. Preuk Taotawin. Dr. Atipong Pathanasethpong contributed his insight on the health section and oered critical understanding on Isan. Invaluable assistance was provided too by: William Klausner helped us to under- stand what Isan used to be and how it has changed; Sukit Sivanunsakul and Suphannada Lowhachai from the National Economic and Social Development Council and Dr.