A Realist Review Protocol of Community Group-Based Programs to Promote Physical Activity in Immigrant Older Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Manx Society Offers Its Congratulations and Best Wishes for a Successful Future

NEWSLETTER Spring 2016 Editor – Douglas Barr-Hamilton Society activities Coming up soon is our Annual General Meeting which will be held on Monday, 7th March 2016. back at Casa Mamma Restaurant, 339 Gray's Inn Road, WC1X 8PX (020 7837 6370) near King's Cross station, the same venue as in recent years. We aim to start the meal at 2.00 p.m. after starting lunch at 12.30 to give us time to eat. One or two will be gathering from just after noon for a pre-lunch drink at chat so if you can join us, please do. Members will receive a copy of the Notice and Agenda with this newsletter. We shall be back at Doubletree by Hilton Hotel, Southampton Row. on Saturday, 7th May 2016 for our Annual lunch. There will not be a lot of time between the next newsletter and this date so if you plan to come, and we certainly hope for a good number again this year, please contact Sam Weller (01223 720607) We know that many Manx Societies enjoy a Christmas get together each year and our rather informal arrangements seem to have fallen by the wayside in 2015. Perhaps now is the time to discuss something for the end of the year. A sample of other groups' celebration follows and the secretary looks forward to ideas arriving. DBH Christmas around the world Southern Africa Our association held its Christmas gathering at my home yesterday and included a programme of Manx tales and a Manx carol interspersed with seasonal readings and traditional Christmas singing ending with the beautiful Ellan Vannin and the Manx National Anthem sung in Manx and English. -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

Risk Factors for Hand Injury in Hurling: a Cross-Sectional Study

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002634 on 16 May 2013. Downloaded from Risk factors for hand injury in hurling: a cross-sectional study Éanna Falvey,1,2 Paul McCrory,3 Brendan Crowley,2 Aiden Kelleher,2 Joseph Eustace,2 Fergus Shanahan,2 Michael G Molloy2 To cite: Falvey É, McCrory P, ABSTRACT et al ARTICLE SUMMARY Crowley B, . Risk factors Objectives: Hurling is Ireland’s national sport, played for hand injury in hurling: a with a stick and ball; injury to the hand is common. A cross-sectional study. BMJ Article focus decrease in the proportion of head injury among Open 2013;3:e002634. ▪ The mandatory use of head and face protection doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013- emergency department (ED) presentations for hurling- in the Irish sport of hurling over the past 002634 related injury has coincided with voluntary use of 10 years has been accompanied by a marked helmet and face protection since 2003. A similar decrease in the presentation of head and facial decrease in proportions has not occurred in hand ▸ Prepublication history and injuries to the emergency department (ED). injury. We aim to quantify hurling-related ED additional material for this ▪ These improved figures have not been seen in paper are available online. To presentations and examine variables associated with hand injury, where presentations to the ED have view these files please visit injury. In particular, we were interested in comparing remained high, despite the availability of a com- the journal online the occurrence of hand injury in those using head and mercially available hand protection device. -

The Ledger and Times, May 18, 1965

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 5-18-1965 The Ledger and Times, May 18, 1965 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, May 18, 1965" (1965). The Ledger & Times. 4814. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/4814 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - • /a , ••••••••• 6 • , • .965 Selected As A Best Al! Round Kentucky Community Newspaper The Only Largest Afternoon Daily Circulation In Murray And Both In City Calloway County • And In County 311tarriy Population 10,100 United Press International Is Our 11th lies; Murray, Ky., Tuesday Afternoon, May 18, 1965 Vol. LXXXV1 No. 117 Seek Argument Of 'Seen & Heard Citizens Grant To Make Possible Eight Lakes State Heads Around To Block Weeks Aid To Pre-SChoolers Area Funds Proceeding I Congressman Frank A. Stubblefield today announced that MURRAY _ • a Head Start oriaisct to weeks of pre-school train- Olinonents of plans to- drop a Lasweasissiasets FRANKFORT. Ky - Lt Gov ing this summer for 22 need., children in Murray will be made 170.010-acre Retween-the-Lrikes re- Dr. Clyde Orr. associate dean far Harry Lee Waterfield said Monday Possible by a contribution 01,53,407 from the Office of Eco- graduate studies a Etiaterti crettional arei in Western Ken- there were ni limits to which Gov. -

April 2021 • Volume 15 - Issue 4

est. 2006 April 2021 • Volume 15 - Issue 4 The Many Stages of Melissa Fitzgerald Editor’s Are you where everybody Corner Do Tell: What’s the SAFE HOME knows your name? By John O’Brien, Jr. New to Cleveland? We’d like to help: Craic in April? April 2021 Vol. 15 • Issue 4 @Jobjr Í Publisher & Editor John O’Brien Jr. THOMAS BODLE teacher at both VASJ and St. Edward hen you are this close in life experiences and writing, that Design/Production Christine Hahn February 1, 1952 - March 5, 2021 High School. He was a devoted basket- Help you get started, to the fire, you can’t affect their columns each month. Website Rich Croft THOMAS M. BO- ball coach, educator and dear friend to Columnists get situated or get always see who is get- I won’t rehash what is within; what Akron Irish Lisa O’Rourke DLE “Coach Bodle,” many student-athletes throughout the tingW warmed. You usually hear the is filling the website, podcast and settled! An Eejit Abroad Conor Makem age 69. Beloved hus- years. Passed away unexpectedly due to screams of those getting burned, but eBulletin; the content continues to At Home Abroad Regina Costello band of Margaret A. complications from COVID-19 on March The road has been paved, and Behind the Hedge John O’Brien, Jr. we are a celebratory paper - not the speak for itself, and surprises are “Margie” (nee Lack- 5, 2021. In lieu of flowers, memorial con- we pay it forward, by helping scorched earth discussion of divorc- good for the soul and the sedentary. -

A Resource Guide

Gaelic Nova Scotia: A Resource Guide Earrann o’n duan “Moladh Albann Nuaidh” Nis o’n thàinig thu thar sàile Chum an àite ghrinn, Cha bhi fàilinn ort ri d’ latha ’S gach aon nì fàs dhuinn fhìn Tighinn do dhùthaich nam fear glana Coibhneil, tairis, caomh, Far am faigh thu òr a mhaireas; Aonghas ‘A’ Rids’ Dòmhnullach á Siorramachd Antaiginis, Tìr Mór na h-Albann Nuaidhe An excerpt from “In Praise of Nova Scotia” Now that you have come from overseas To this fair place You will lack for nothing all your days As all things fare well for us; Coming to the land of fine people Kindly, gentle and civil, Here you will find lasting gold; Angus ‘The Ridge’ MacDonald, Antigonish County, Mainland Nova Scotia CONTENTS Introduction I The Gaels 1 Culture 23 Language 41 History 45 Appendices 56 Online Resources 56 Gaelic Names 58 Cross-Curricular Connections 60 Resources 66 Gaelic Calendar 67 The Seasons 69 Calum Cille: Naomh nan Gàidheal Saint Columba: The Saint of the Gaels 70 Gaelic World Map 1500AD 71 Irish Nova Scotians: Gaels, Irish Language and Cultural Heritage 72 Tìr is Teanga: The Nova Scotia Gael and Their Relationship to the Environment 76 Glossary of Terms 80 Bibliography 82 INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES Nova Scotia’s Culture Action Plan: Creativity and This resource guide is intended to help educa- Community 2017 supports Nova Scotia's Action tors accomplish five key tasks: Plan for Education 2015 which states that the • help Nova Scotians to understand Gaels language, history, and culture of Gaels should and their unique Gaelic language, culture, be taught in grades primary to 12. -

The Pipes of Christmas the 16Pipesth Anniversary, of 1999Christmas - 2014

The Pipes of Christmas The 16Pipesth Anniversary, of 1999Christmas - 2014 Proudly presented by the Clan Currie Society. Step Back In Time The Grand Summit Hotel Welcomes you in an historic and picturesque setting. 150 spacious and luxurious guest rooms including five grand Presidential Suites. Home of the HAT Tavern. An exceptional catering staff who will indulge your THE PIPES guests with elegant cuisine and unsurpassed service, no matter what the occasion or special event, in the comfort and elegance of our Grand Ballroom. OF Providing generous hospitality for over 130 years CHRISTMAS (908) 273-3000 www.grandsummit.com 570 Springfield Ave., Summit, NJ Presented by The Clan Currie Society Proud sponsor of The Pipes of Christmas More than 6,000 international students from over 100 different countries worldwide call Edinburgh Napier home. They live in Scotland’s inspiring capital, renowned as the world’s international festival city, and learn with confidence in developing excellent career prospects. More than 95.4% of our students are in work or further education within six months of graduation*. Photos: our Craiglockhart campus Find out more at: and graduates in Edinburgh. www.napier.ac.uk Edinburgh Napier University is a registered Scottish charity. Reg. No. SC018373. *UK Higher Education Statistics Agency 2013. IDEA 2437. 431 Springfield Avenue, Summit, New Jersey 07901 phone: (908) 277-1398 • www.LoisSchneiderRealtor.com The Clan Currie Society proudly presents The 16th Annual Production of TheThe Pipes ofof ChristmasChristmas! Sponsored by Edinburgh Napier University The Grand Summit Hotel Saturday, December 20, 2014 Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church New York City Sunday, December 21, 2014 Central Presbyterian Church Summit, NJ There will be one fifteen-minute intermission. -

Read Journal

OnlineISSN:2249-460X PrintISSN:0975-587X DOI:10.17406/GJHSS BlackAfricanWomenʼsAgencyAboriginalEcoconsciousness TheComplexofDreamsFormationEmployeeswithVisualImpairment PublicServiceEmploymentinUgandaTheGoodAdministrationofTaxJustice LightaboutColorortheSchizophrenicAPassionateRefashioningofthePoetʼs VOLUME21ISSUE2VERSION1.0VOLUME21ISSUE1VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Global Journal of Human-Social Science: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 21 Issue 2 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2021. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ Globa l Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ -

Wojciech Lipoński Professor Wojciech Lipoński (B

Wojciech Lipoński Professor Wojciech Lipoński (b. 1942) specialises in two fields of research: British studies and the history of sport. He is the author of 16 books in which these two fields are frequently linked. His best works include The Origins of Civilization in the British Isles (1995) and A History of British Culture (2003), which were reprinted in several editions and published in Polish. They both obtained prestigious awards from the Polish Ministry of Science and Academic Education and his History of British Culture was also named the Best Academic Book in Poland of 2004. In 1987, Professor Lipoński established a biannual academic journal Polish-Anglo-Saxon Studies, of which he is still editor in-chief. His books on sport include World Sports Encyclopedia published in Polish, English and French under UNESCO auspices (2001- 2006), and A History of Sport (2012). Both were awarded with Olympic Laurels by the Polish Olympic Committee. He is a member of the British Society of Sports History and his papers have been LANDMARKS IN BRITISH HISTORY AND CULTURE translated into as many as 12 languages in international journals and conference proceedings. Landmarks in British History and Culture examines selected issues crucial in the development of British civilization. It consists of fragments of Professor Lipoński’s earlier publications together with the full texts of previously unpublished lectures, which are now arranged chronologically in order to form a new historical Wojciech Lipoński and cultural narrative. It contains views which are typical for standardised British historiography, but with the advantage of the outsider’s perspective, it also tries to add new interpretations and hypotheses, explaining, for example, the lack of English LANDMARKS IN BRITISH HISTORY protagonists in Old English epics or suggesting that it was England where the oldest European trading union of towns was created before the Hanseatic League. -

The Incredible World of Sports Events

The Incredible World of Sports Events AIRSPORTS Softball Boule lyonnaise Aerobatics Fast Pitch Bowls Gliding aerobatics Slow Pitch Curling Air racing Modified Pitch Ice stock sport Ballooning 16 Inch Klootschieten Cluster ballooning Bat-and-Trap Petanque Hopper ballooning British baseball - four posts Shuffleboard Wingsuit flying Brannboll - four bases Var pa Gliding Corkball - four bases Hang gliding (no base-running) BOWLING Powered hang glider Cricket - two wickets Candlepin bowling Human powered aircraft Indoor cricket Duckpin bowling Model aircraft Limited overs cricket Five-pin bowling Parachuting One Day International Skittles (sport) Banzai skydiving Test cricket Ten-pin bowling BASE jumping Twenty20 Marbles games Skysurfing Danish longball Lawn bowling Wingsuit flying Globeball - four bases Kickball Paragliding CATCH GAMES Powered paragliding Lapta - two salos (bases) The Massachusetts Game - Curving Ultralight aviation Dodge ball Paramotoring four bases Mat ball Ga-ga Meta and longa meta (long meta) - Hexball ARCHERY Hungarian game Keep Away Jujutsu Clout archery Oina - One (Two, Three, or Four) Kin-Ball Judo Field archery Old Cat - variable Prisoner Ball Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Flight archery Over-the-line - qv Rundown (aka Pickle) Samba (martial art) Gungdo Pesapallo - four bases Yukigassen Sumo Indoor archery Podex Wrestling Kyodo Punch ball CLIMBING Amateur wrestling Popinjay Rounders - four bases or posts Canyoning Greco-Roman wrestling Target archery Scrub baseball - four bases (not a Rock Climbing Freestyle wrestling team -

A Stockingful of Scottish Christmas Traditions

December 2018 Volume 9, Issue 12 A stockingful of Scottish Christmas traditions The Scotsman | December 20, 2005 SCOTTISH Christmas traditions are – to say the least – a little on the patchy side. There are some great pagan ideas, first-rate medieval treats, but then there is a huge yawning chasm, a Christmas- free zone until the middle of the 20th century until it all came back into fashion. The reason for this dearth of Christmas cheer is that Scotland in the mid-16th century had its very own Grinch. Yes, just like the character in Dr Seuss's book who stole Christmas, John Knox and the newly reformed Church of Scotland cancelled the festive season. They forbade anyone to celebrate this erstwhile season of goodwill, hounded those who broke the embargo and cast a gloomy Decem- ber shadow that stretched down through the centuries. But we canny Scots, unwilling to forego a good party, simply moved the traditions a week along. From this came the Scottish emphasis on Hogmanay. Christmas was not recognised as a public holi- day in Scotland until 1958 and up until then people continued to work, saving their fun until New Year's Eve. So simply put, if you want a traditional Scottish Christmas then get up as usual, go into work as normal, return home to a bowl of soup and an early night! But that wouldn't be much fun. So we've trawled the distant past to find out what Scots would have been doing long, long ago, to give you some tips on how to celebrate a guid Scottish Christmas. -

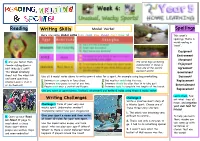

Spellings Reading Writing Skills

, Reading Writing Skills Modal Verbs! Spellings s Here are some modal verbs (can, could, may, should, must, have to) This week’s spellings theme is words ending in ‘ment’. Equipment Environment Movement The world bog snorkelling 1. Are you faster than championship in Wales is Enjoyment cheese rolling down a hill? Why do I ask?? truly one of the world’s Agreement wackiest sports! The Visual Literacy Government sheet has the video link Use all 6 modal verbs above to write down 6 rules for a sport. An example using bog snorkelling: Document and some questions. 1. Swimmers can compete in fancy dress. 2. Bad weather could stop the race. Choose Level 1, 2 or 3 Replacement 3. Swimmers may pause to rest at any time. 4. Swimmers should be older than 14 to take part. Entertainment or do them all! 5. People must wear a snorkel and flippers. 6. Swimmers have to complete two lengths of the trench. Replacement Use any sport or game (chess, football, whatever!) and write 6 rules using these 6 modal verbs! Learn them, find Challenge 2 Writing Challenges out what they all Write a creative short story of mean, and organise Challenge 1 Think of your very own a Wacky Sport. Choose one of your own test for wacky sport. Underwater snooker? these three story starters: Friday! Trampoline tennis? Use your imagination. 1. The zebra was becoming very 2. Open up your Read Give your sport a name and then write difficult to control… To help you learn at least 10 rules for your new sport.