The Geography of Inequalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4203 SLT Brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1

4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1 South London Trams Transport for Everyone The case for extensions to Tramlink 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 2 South London Trams Introduction South London Partnership Given the importance of good Tramlink is a highly successful integrated transport and the public transport system. It is is the strategic proven success of Tramlink reliable, frequent and fast, offers a partnership for south in the region, South London high degree of personal security, Partnership together with the is well used and highly regarded. London. It promotes London Borough of Lambeth has the interests of south established a dedicated lobby This document sets out the case group – South London Trams – for extensions to the tram London as a sub-region to promote extensions to the network in south London. in its own right and as a Tramlink network in south London, drawing on the major contributor to the widespread public and private development of London sector support for trams and as a world class city. extensions in south London. 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 4 South London Trams Transport for Everyone No need for a ramp operated by the driver “Light rail delivers The introduction of Tramlink has The tram has also enabled Integration is key to Tramlink’s been hugely beneficial for its local previously isolated local residents success. Extending Tramlink fast, frequent and south London community. It serves to travel to jobs, training, leisure provides an opportunity for the reliable services and the whole of the community, with and cultural activities – giving wider south London community trams – unlike buses and trains – them a greater feeling of being to enjoy these benefits. -

Norbury Road, Thornton Heath, Surrey, CR7 £450,000 Freehold

Norbury Road, Thornton Heath, Surrey, CR7 £450,000 Freehold 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, Surrey, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Norbury Road, Thornton Heath, Surrey, CR7 £450,000 Freehold “We bought this home in 2017 as our first step on the property ladder. The Yellow House really drew us in and when we got inside we could see that it was exactly what we wanted. The hardwood timber flooring in the living and dining area as well as the lobby was a real plus straight away but it was the amount of natural light in the living area that quickly caught the eye. Big windows, glass doors into the extension and conservatory type glazing into the back garden. The kitchen is a dream space-wise and the cooker was one of the first things we both mentioned after we viewed the house as we both love to cook. The garden is really spacious and has been great for hosting people and barbecues in the summer. The downstairs toilet off the extension is perfectly located for this too. 3 bedrooms upstairs with 2 large doubles is great. The 3rd is perfect for a single room but also ideal for an office, or in our case, a home gym! We redecorated when we moved in to brighten it up further and add our own stamp on the house. With the space available, the options for furnishing are endless. The house is a short walk to Thornton Heath station, which has very quick links in to Central London as well Croydon and Gatwick airport. -

London Low Emission Zone – Impacts Monitoring, Baseline Report

Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Greater London has well over 100 air quality monitoring sites that are currently in operation, most of which are owned by local authorities and are part of the London Air Quality Network (LAQN). Defra also has a number of monitoring sites in London, which are part of the UK’s automatic network. Figure A5.1 shows the distribution of these monitoring sites in London. This appendix summarises the different monitoring networks and outlines which monitoring sites have been used for the analysis undertaken in this report, results of which are discussed in sections 8 and 10. Figure A5.1 Location of monitoring sites currently in operation in Greater London. A5.1 London Air Quality Network (LAQN) The LAQN is facilitated by London Council’s on behalf of the London boroughs who fund the equipment. The network is operated and managed by Kings College London and real-time data is available at www.londonair.org.uk. Table A5.1 lists the LAQN sites which are currently in operation in London. Impacts Monitoring – Baseline Report: July 2008 1 Appendix 5: Air quality monitoring networks Table A5.1 List of operating London Air Quality Network sites in London (as of end 2007). Borough and site name Site classification Barking & Dagenham 1 Rush Green suburban Barking & Dagenham 2 Scrattons Farm suburban Barking & Dagenham 3 North Street roadside Barnet 1 Tally Ho Corner kerbside Barnet 2 Finchley urban background Bexley 1 Slade Green suburban Bexley 2 Belvedere suburban -

The Rt Revd the Bishop of Southwark by Email Only Dear Bishop Mission

The Rt Revd the Bishop of Southwark Rex Andrew Pastoral By email only Our ref: NB37/256b 30 October 2020 Dear Bishop Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Benefice and parish of All Saints, Spring Park; and parishes of St George, Shirley; and Shirley (also known locally as St John, Shirley) Proposed Pastoral Scheme Following the publication of the draft Pastoral Scheme providing for: (i) the dissolution of the benefice and parish of All Saints, Spring Park and the division of the area of its parish between the parishes of St George, Shirley; and Shirley (also known locally as St John, Shirley); (ii) the parish church of All Saints, Spring Park to become a chapel of ease in the parish of Shirley; (iii) the transfer of the parsonage house of the benefice of All Saints, Spring Park to the Southwark Diocesan Board of Finance as diocesan glebe we received 45 representations against the draft Scheme, 12 in favour, three letters of comment and five which were received out of time (one of which consists of photographs supplementing a representation made within time). The draft Scheme carried the following as the diocesan rationale for your proposals: As the result of ongoing concerns about the financial viability and capacity for governance and mission going forward, the Bishop of Southwark held a Visitation to the parish of All Saints, Spring Park in 2016. This was conducted by the Bishop and Archdeacon of Croydon. A series of Directions were issued as a result of this, designed to help the parish to address these areas. There has sadly been no evidence that this has been the case nor has the parish demonstrated the future capacity to do so. -

Buses and Trams from Croydon Arena and South Norwood Leisure Centre

Buses and trams from Croydon Arena and South Norwood Leisure Centre Buses and trams from Croydon Arena and South Norwood Leisure Centre 197 towards Peckham Bus Station Lawrie Park Road from stops PG, PH, WJ Penge West PENGE197 towards Peckham Bus Station PengeLawrie PawleynePark Road Arms from stops PG, PH, WJ Penge West SOUTH PENGE 130 NORWOOD CroydonPenge Pawleyne Road Arms from stops PG, PH, WJ Norwood Junction 130 Grosvenor Road ANERLEY Thornton Heath Thornton Heath Selhurst Park Stadium South Norwood 197 Anerley Mitre Parchmore Road Clock Tower Crystal Palace Football Club Clock Tower SOUTH 312 130 130 NORWOOD from stops Croydon Road PG, PH, WJ from stops PG, PH, WJ Norwood Junction ANERLEY THORNTON 130 GrosvenorNorwood Road 197 BECKENHAM 197 Anerley Mitre Thornton Heath HEATHThornton Heath Selhurst Park Stadium South Norwood312 Junction 197 Parchmore Road Clock Tower Crystal Palace Football Club Clock Tower Clifford Road Beckenham Beckenham Doyle Road 312 130 Road Junction 130from stops PG, PH, WJ London Trams THORNTON London Trams Avenue Road BECKENHAM289 130197 Norwood 197 from stop Tram Stop HEATH 197312 Junction from stop LC 312 Clifford Road Birkbeck Beckenham Beckenham Doyle Road Road Junction London Trams 130 Harrington Road from stop Tram Stop London Trams Avenue Road Elmers End 130 London Trams from stop Tram Stop 289 T ROAD 197 AS from stop LC 312BELF Birkbeck Ȟ Ȥ South Norwood Elmers End ALBERT ROAD Country Park London Trams PO Tesco Harrington Road from stop Tram Stop R T L 289 Elmers End AND ROA WATCOMBE ROAD T ROAD -

Surrey. Crovdon

DIRECTORY.) SURREY. CROVDON. 1~3 Norman Albert E. 61 Broughton road, Paget Peter, 6 Wellesley road Payne Charles Wynter, 102 Park lane Thornton Heath Paget Waiter Gray, 52A, Waddon road Payne Miss, 28 Blenheim Park road Norman Albert John, 12 Campden road Pagneguy Jules Maurice, 103 Norbury Payne Mrs. 33 Norbury crescent, Norbury Norman Benjamin A. 5 Blenheim Park rd crescent, Norbury Payne Mrs. 28 St. Paul's rd.Thrntn.Htb Norman Edwin G. 51 Brigstock road. Paice Aug. Fredk. 24 South Park Hill road Pa.yne William Joseph, 53 Lyndhurst Thornton Heath Paice George, 4 W arrington road road, Thornton Heath Norrington llrs. 17 Coombe road Paice W. A. 55 Beulah rd. Thornton Heath Pazzi Massimo, lO St. John's grove Norris Mrs. 1 Colworth road Pain Waiter Alfred Gregson, Clievden, Peach John, Mayfield, Sandfield road, Northa.m John Willia.m, 45 Broughton · Pampisford road Thornton Heath road, Thornton Heath Paine Claud Heather, 35 Kidderminster rd Peacock John S. 90 Avondale road Norton Frank, 58 Melfort rd.Thorntn.Hth Paine Fdk. 126 Brigstock rd.ThorntonHth Peacock Mrs. Thomas, 3 Warham road Norton Howard, Glenroy, Brownlow road Painter Arth11r Edm1md, Cranford, 8 Peake }'rederick John Seaman, 8 Ca.rew Norton Robert, 3 Lyndhurst gardens, Coombe road road, T.ilornton Heath Lower Addiscombe road Painter Mrs. 39 Bensham :Manor road, Peake Mrs. 14 Waldrons Norton Robert Minns, 3 Outram road Thornton Heath Pearce Alfd. Hinton, Norbury aven.Nrbry Norton Waiter Chas. 17 Normanton rd Pa.ish Louis Williaru, ~:>Northampton rd Pearce Edwd. 2o Beulah rd. Thorntn.Hth Novion Francis, 3 Upper Coombe street Palfrey Miss, 3 Coombe road Pearce Edward .Nat.haniel, 35 Lyndhurst Nowakowski John S. -

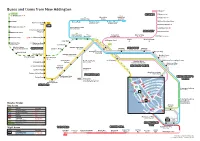

Buses and Trams from New Addington

Buses and trams from New Addington 314 Eltham Tramlink 3 Eltham Church to Wimbledon ELTHAM Woodside Norwood New Eltham Addiscombe Green Junction 130 William Barefoot Drive Mitcham Shirley Park Morland Road Portland Road Thornton Heath 64 Blackhorse Lane Croydon Arena Pond Elmstead Woods N64 Mitcham Junction Upper Shirley Road Sundridge Park Shirley Windmill Croydon University Beddington Lane Hospital BROMLEY Plaistow Green Coombe Lane Coney Hall Bourne Vale for Addington Hills Gravel Hill Addington Road Eastway Bromley The Glades Therapia Lane West Croydon Hayes Bromley South Lloyd Park Addington Road Ampere Way Wellesley Road for Valley Park for Whitgift Centre Sandilands T32 Waddon Marsh Selsdon Park Road for Purley Way Retail Park CROYDON Lebanon Road Gravel Hill Fieldway FIELDWAY Fieldway Applegarth North Walk Addington Village Merrow Way Wandle Park Interchange George Street Selsdon Park Road Featherbed Lane Headley Drive Church Street East Croydon Frimley Close John Ruskin Fieldway Goldcrest Community Centre Featherbed Lane Headley Drive Park Hill Road College Yew Tree Way Dunley Drive (west arm) Goldcrest Way King Henry’s Drive South Croydon Selsdon HEADLEY DRIVE Park Road Monks Hill Forestdale Croham Road The Green King Henry’s Drive Croham Valley Road FORESTDALE Tilford Avenue Addington Road Farley Road Selsdon Crescent KING HENRY’S L E. Forestdale O AV T31 D ILL IVE DRIVE G E H DR Court Wood Lane/Markfield E STL Y’S CA NR Selsdon L E ESCENT for Selsdon Nature Reserve A H EY CR N R NG OLS Old Farleigh Road E Q KI W CRESCENT S RICH SELSDON P ALD T CRESCENT XTON M HA D O S A N O King Henry’s Drive T R A E ROAD C VILL Kestrel Way U REN E N P T G N A E IG King Henry’s R R ROAD O D ELL C K . -

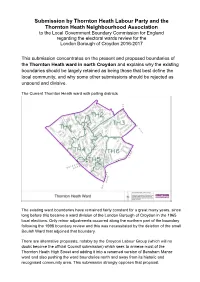

Submission by Thornton Heath Labour Party and the Thornton

Submission by Thornton Heath Labour Party and the Thornton Heath Neighbourhood Association to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England regarding the electoral wards review for the London Borough of Croydon 2016-2017 This submission concentrates on the present and proposed boundaries of the Thornton Heath ward in north Croydon and explains why the existing boundaries should be largely retained as being those that best define the local community, and why some other submissions should be rejected as unsound and divisive. The Current Thornton Heath ward with polling districts The existing ward boundaries have remained fairly constant for a great many years, since long before this became a ward division of the London Borough of Croydon in the 1965 local elections. Only minor adjustments occurred along the northern part of the boundary following the 1998 boundary review and this was necessitated by the deletion of the small Beulah Ward that adjoined that boundary. There are alternative proposals, notably by the Croydon Labour Group (which will no doubt become the official Council submission) which seek to annexe most of the Thornton Heath High Street and adding it into a renamed version of Bensham Manor ward and also pushing the ward boundaries north and away from its historic and recognised community area. This submission strongly opposes that proposal. The table above is the Council’s calculations for the 2016 and 2022 electorate after calculating population growth and taking into account predicted residential developments. The Council’s own calculations state that the overall electorate will increase from: 264,126 in 2016 to 281,944 in 2022 The average electorate per councillor will increase from: 3,773 in 2016 to 4,028 in 2022 In particular the Thornton Heath electorate will increase from: 11,238 in 2016 to 11,635 in 2022 A variance of -1% in 2016 to a variance of – 4% in 2022. -

Norbury History Chronology

WHAT HAPPENED IN NORBURY? An Introductory Chronology Pollards Hill Recreation Ground Fountain & former Age Concern UK office Norbury Library Norbury Park Norbury Brook Sean Creighton History & Social Action Publications 2017 1 Introduction Norbury is a district in North Croydon with borders with the Streatham district of the London Boroughs of Lambeth and with parts of Merton. The name ‘Norbury’ is an abbreviation of ‘Northborough’. ‘Borough’ originally meant a certain manor or district. What became Croydon contained several boroughs. Reference to these was dropped when Croydon was incorporated as a County Borough in 1888. This chronology has been compiled to help stimulate interest in Norbury’s history. The first modern history of the area A History of Norbury by David Clark was published by the Streatham Society in 2013. It has been through several reprints but is now out of print. It can be read at Norbury Library. David occasionally gives talks about Norbury’s history and leads walks in the area. I am a historian whose interests include Croydon and Norbury, where I live. History & Social Action Publications is my publishing imprint. I am an individual member of the Croydon Local Studies Forum, and co-ordinator of the Croydon Radical History Network. I hope that this introduction will inspire readers to research aspects of interest to them. One of the easiest ways is to look at the local newspapers from the 1860s at Croydon Museum’s Local Studies Research Room at the Clocktower at Croydon Town Hall complex in Katharine St. Sean Creighton February 2017 [email protected] Prehistoric Period 1459. -

Buses from Norwood Junction

Buses from 196 Peckham Town Centre 197 Lewisham 75 Elephant & Castle PECKHAM Peckham Rye LEWISHAM Kennington Lane Kennington Road Lewisham Hospital Peckham Rye East Dulwich Road Norwood Junction Vauxhall Bus Station Dulwich Library Catford Wandsworth Road Lansdowne Way Lewisham Town Hall Horniman Museum Stockwell Crystal Palace BRIXTON Crystal Palace for National Anerley Road CATFORD Catford and Brixton Parade Sports Centre Thicket Road Anerley Park Forest Hill 157 Catford Bridge Sydenham Kirkdale Herne Hill Dulwich Road 410 Crystal Palace Anerley Hill Hamlet Road Catford Hill Tulse Hill Norwood Road Anerley Lawrie Park Road Anerley Road Perry Vale Siddons Road Key West Norwood CRYSTAL Maberley Road Belvedere Road Penge West Norwood Crown Point PALACE Mayow Road NORWOOD Maberley Road Harris City Academy Anerley Road Penge High Street/ Ø— Connections with London Underground Beulah Hill Maple Road Sydenham Newlands Park Biggin Hill Seymour Villas u Connections with London Overground Sylvan Road Cantley Gardens Penge East Beulah Hill Convent Hill R Connections with National Rail Penge Pawleyne Arms Beulah Hill Hermitage Road Auckland Road Auckland Rise Anerley Road Î Maple Road PENGE Connections with Docklands Light Railway Beulah Hill Beulah Spa Croydon Road Avenue Road h Auckland Road Cypress Road Connections with Tramlink Beulah Hill Upper Beulah Hill ANERLEY Croydon Road Anerley Road/Oak Grove Road  Connections with river boats Upper Norwood All Saints’ Church Auckland Road Howden Road Croydon Road Elmers End Road for South Norwood Lake South Norwood Hill Grange Avenue Croydon Road Samos Road South Norwood Hill Wharncliffe Gardens Lancaster Road Warminster Road Anerley Mitre South Norwood Hill Howden Road Southern Avenue A Croydon Road Selby Road South Norwood Hill Elm Park Road Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus Penge Road Sunnybank service. -

Buses Fron Broad Green (Croydon)

BRIXTON STREATHAM ELMERS END CROYDON PURLEY COULSDON Buses from Broad Green (Croydon) Key N109 continues to Oxford Circus 60 Day buses in black 24 hour Brixton 109 250 service BRIXTON N64 Night buses in blue Brixton Hill —O Connections with London Underground o Connections with London Overground Streatham Hill R Connections with National Rail T STREATHAM Streatham Connections with Tramlink St Leonard’s Church M Streatham Vale Greyhound Lane Night journeys only 24 hour 264 service Streatham Tooting Streatham Common 60 St George’s Hospital Greyhound Terrace Streatham Common Greyhound Tooting Broadway Rowan Road Streatham High Road Tooting Norbury Green Lane Wide Way Ivy Gardens London Road Parchmore Road Pollards Hill Ederline Avenue Sandfield Road Route finder Mitcham Library Fair Green Galpins Road Galpins Road South Lodge Avenue Silverleigh Road London Road London Road Day buses including 24-hour services Mitcham Road Yorkshire Road Galpins Road Rochford Way Galpins Road Bus route Towards Bus stops Goldwell Road London Road Parchmore Road Mitcham Road Langdale Road Parchmore Methodist Church Therapia Lane/Croydon Cemetery 60 Old Coulsdon +l,n Thornton Road Thornton Heath London Road Brigstock Road Brigstock Road Mitcham Road Peall Road Fairlands Avenue Colliers Water Lane Frant Road Quadrant Road Thornton Heath Thornton Heath Streatham +olf Brading Road High Street New Addington Mitcham Road Thornton Road 64 +l,n Lombard Croydon Crematorium Brigstock Road Brigstock Road Brigstock Road Thornton Heath Ockley Road Roundabout Thornton Heath -

Dementia Action Week 20-26 May 2019 - Events in Croydon

EVE DEMENTIA ACTION WEEK 20-26 MAY 2019 - EVENTS IN CROYDON Tuesday 21 May Wednesday 22 May Thursday 23 May Friday 24 May Dementia Friendly Film Croydon University Hospital BME Forum dementia event What's New in Dementia SUMMER HOLIDAY (1963) stars A whole day to promote awareness of Opportunity to talk to the Dementia Opportunity for carers and people Cliff Richard and The Shadows. dementia including: Nurse from Croydon University with dementia to experience other Four young London Transport Hospital therapies such as massages mechanics convert a double 12 hour knit-a- thon - from 8.00am- Try a hand massage and learn about decker bus into a travelling hotel, 8.00pm making twiddle mats & cuffs the benefits WHAT which they drive across Europe on for those living with dementia Have fun with our gentle exercise their way to Athens. Decorating Zimmer frames session CDAA members information stand Hear the latest news from the Carers Admission is free for people with Cupcake/cake sale for CUH Support Centre in Croydon dementia and their carers. Dementia Friends session (open to Give your views on the ‘Want some all), is about learning more about help?’ leaflet Tea, coffee and biscuits provided dementia and the small ways you Network with other carers from 10.30 before the screening. can help and help create dementia Take away lots of useful information friendly communities. Dementia Friends session lasts around one hour. (10.15am – 11.30am) David Lean Cinema, Croydon University Hospital Haslemere Hall, 2A Haslemere Road, Marsh & Willow Day Service Clocktower Building, Katharine Main Reception, 530 London Thornton Heath, Croydon, CR7 7BE Heaver's Centre, 122 Selhurst WHERE Street CR9 1ET Road, Croydon, CR7 7YE Road, London, SE25 6LL To book, please contact: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/deme Anna D'Agostino - 020 8684 3719 Those interested are welcome to turn ntia- friendly-screening-of-summer- up.