A Multi-Scale Model of Disease Transfer in Honey Bee Colonies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimating the Density of Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera) Colonies Using

Apidologie Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature, 2019 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-019-00671-2 Estimating the density of honey bee (Apis mellifera ) colonies using trapped drones: area sampled and drone mating flight distance Patsavee UTAIPANON , Michael J. HOLMES, Nadine C. CHAPMAN, Benjamin P. OLDROYD Behaviour and Genetics of Social Insects Laboratory, Ecology and Evolution, University of Sydney, Macleay Building A12, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Received 12 December 2018 – Revised 20 April 2019 – Accepted 24 June 2019 Abstract – Reliable information on Western honey bee colony density can be important in a variety of contexts including biosecurity responses, determining the sufficiency of pollinators in an agroecosystem and in determining the impacts of feral honey bees on ecosystems. Indirect methods for estimating colony density based on genetic analysis of sampled males are more feasible and cost efficient than direct observation in the field. Microsatellite genotypes of drones caught using Williams drone trap are used to identify the number of colonies (queens) that contributed drones to a mating lek. From the number of colonies, the density of colonies can be estimated based on assumptions about the area from which drones are drawn. This requires reliable estimates of drone flight distance. We estimated average minimum flight distance of drones from feral colonies along two 7-km transects in Southern NSW, Australia. We found that drones from feral colonies flew at least 3.5 km to drone traps. We then determined that the maximum distance that drones flew from a focal colony to a trap was 3.75 km. -

Honey Bees Identification, Biology, and Lifecycle Speaker: Donald Joslin Hive Consists of Three Types of Bees ◦ Queen, Drone and Worker

Honey Bees Identification, Biology, and Lifecycle Speaker: Donald Joslin Hive consists of three types of bees ◦ Queen, Drone and Worker For Year Color: Ending In: White 1 or 6 Yellow 2 or 7 Red 3 or 8 Green 4 or 9 Blue 5 or 0 Queen Marking Colors Queen Only Fertile female in the Hive Can lay 2000 eggs each day She can live 5 years, 3-years average One per colony usually Mates in flight with 7-150 drones Queen Her thorax is slightly larger No pollen baskets or wax glands Stinger is smoother and curved (and reusable) The Honey Bee Colony Queen Pheromones ◦ The “social glue” of the hive ◦ Gives the colony its identity and temperament ◦ Sends signals to the workers Mates once, in flight, with 7 to 150 drones Lays both fertilized and unfertilized eggs Fertilized eggs become workers or Queens Unfertilized eggs become drones How does an egg become a queen instead of a worker? ◦ Royal Jelly is fed to the larvae for a much longer period of time ◦ Royal Jelly is secreted from the hypopharynx of worker bees Royal Jelly Supercedure Cell (Never cut these unless you have a replacement queen ready) Basic Anatomy Worker ◦ Sterile female ◦ Does the work of the hive ◦ Have specialized body structures Brood food glands – royal jelly Scent glands (pheromones) Wax glands Pollen baskets Barbed stingers – Ouch! The Honey Bee Colony Worker Bees Perform Roles ◦ Nurse ◦ Guard ◦ Forager Castes Worker bees progress through very defined growth stages ◦ When first hatched they become Nurse Bees Clean cells, keeps brood warm, feed larvae Receive -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School Entomology Department HONEY BEES and INTESTINAL DISEASE

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Entomology Department HONEY BEES AND INTESTINAL DISEASE: MOLECULAR, PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES OF HONEY BEES (APIS MELLIFERA) TO INFECTION WITH MICROSPORIDIAN PARASITES A Dissertation in Entomology by Holly L. Holt 2015 Holly L. Holt Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2015 The dissertation of Holly L. Holt was reviewed and approved* by the following: Christina Grozinger Professor of Entomology, Director of The Center for Pollinator Research Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Diana Cox-Foster Professor of Entomology Kelli Hoover Professor of Entomology James H. Marden Professor of Biology Gary W. Felton Professor of Entomology Head of the Department of Entomology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Pollinators are integral to modern agricultural productivity and the continued survival and vitality of natural ecosystems. However, recent declines in pollinator populations and species diversity threaten both food security and the architecture of natural habitats. Due to their vital role in agriculture, honey bees (Apis mellifera) have served as a model organism for investigating the alarming and widespread diminution of pollinator populations. Indeed, surveys from both North America and Europe report large annual colony losses. Parasites along with chemical exposure, poor nutrition, climate change and habitat destruction are frequently cited as leading causes of colony loss. Honey bee colonies are assaulted by a battery of bacterial, fungal and viral pathogens in addition to other parasitic arthropods including mites and beetles. Novel, cost- effective disease management practices are desperately needed to preserve colony health. Basic studies investigating honey bee immunity and disease pathology lay the groundwork for developing efficacious diagnostic tools and treatments. -

Downloaded From

HoneybeeLives.org Honeybees are insects, and like all insects, bees have six legs, a three-part body, a pair of antennae, compound eyes, jointed legs, and a hard exoskeleton. The three body parts are the head, thorax, and abdomen (the tail end). Honeybees live in a highly evolved social structure called a colony, with each bee working towards the good of the hive as a whole. The bees in the colony must be considered as one organism. Within this organism are three distinct kinds of bees. Worker Drone Queen Queen Bee There is only one queen per hive. The queen is the only bee with fully developed ovaries. A queen bee can live for 3-5 years. At the beginning of her life, the queen takes one, or two, “mating flights.” She is inseminated by several male (drone) bees, not necessarily from her hive, and requires no other input of sperm during her life. At the height of her laying season each year, from early spring into mid-summer, she lays up to 2000 eggs per day. Fertilized eggs become female (worker bees) and unfertilized eggs become male (drone bees). When she dies, or becomes unproductive, the other bees will "make" a new queen, sometimes two or three, by selecting a young larva and feeding it a diet solely of "royal jelly". For queen bees, it takes 16 days from egg to emergence. The queen bee will only sting another queen bee in a struggle for dominance in the hive Worker Bee All worker bees are female, but they are not able to reproduce. -

Melissa 6, January 1993

The Melittologist's Newsletter Ronald J. McGinley. Bryon N. Danforth. Maureen J. Mello Deportment of Entomology • Smithsonian Institution. NHB-105 • Washington. DC 20560 NUMBER-6 January, 1993 CONTENTS COLLECTING NEWS COLLECTING NEWS .:....:Repo=.:..:..rt=on~Th.:..:.=ird=-=-PC=A..::.;M:.:...E=xp=ed=it=io:..o..n-------=-1 Report on Third PCAM Expedition Update on NSF Mexican Bee Inventory 4 Robert W. Brooks ..;::.LC~;.,;;;....;;...:...:...;....;...;;;..o,__;_;.c..="-'-'-;.;..;....;;;~.....:.;..;.""""""_,;;...;....________,;. Snow Entomological Museum .:...P.:...roposo.a:...::..;:;..,:=..ed;::....;...P_:;C"'-AM~,;::S,;::u.;...;rvc...;;e.L.y-'-A"'"-rea.:o..=s'------------'-4 University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 66045 Collecting on Guana Island, British Virgin Islands & Puerto Rico 5 The third NSF funded PCAM (Programa Cooperativo so- RESEARCH NEWS bre Ia Apifauna Mexicana) expedition took place from March 23 to April3, 1992. The major goals of this trip were ...:..T.o..:he;::....;...P.:::a::.::ra::.::s;:;;it:..::ic;....;;B::...:e:..:e:....::L=.:e:.:.ia;:;L'{XJd:..::..::..::u;,;;:.s....:::s.:..:.in.:..o~gc::u.:.::/a:o.:n;,;;:.s_____~7 to do springtime collecting in the Chihuahuan Desert and Decline in Bombus terrestris Populations in Turkey 7 Coahuilan Inland Chaparral habitats of northern Mexico. We =:...:::=.:.::....:::..:...==.:.:..:::::..:::.::...:.=.:..:..:=~:....=..~==~..:.:.:.....:..=.:=L-.--=- also did some collecting in coniferous forest (pinyon-juni- NASA Sponsored Solitary Bee Research 8 per), mixed oak-pine forest, and riparian habitats in the Si- ;:...;N:..::.o=tes;.,;;;....;o;,;,n:....:Nc..:.e.::..;st;:.;,i;,:,;n_g....:::b""-y....:.M=-'-e.;;,agil,;;a.;_:;c=h:..:..:ili=d-=B;....;;e....:::e..::.s______.....:::.8 erra Madre Oriental. Hymenoptera Database System Update 9 Participants in this expedition were Ricardo Ayala (Insti- '-'M:.Liss.:..:..:..;;;in..:....:g..;:JB<:..;ee:..::.::.::;.:..,;Pa:::..rt=s=?=::...;:_"'-L..;=c.:.:...c::.....::....::=:..,_----__;:_9 tuto de Biologia, Chamela, Jalisco); John L. -

10. Production and Trade of Beeswax

10. PRODUCTION AND TRADE OF BEESWAX Beeswax is a valuable product that can provide a worthwhile income in addition to honey. One kilogram of beeswax is worth more than one kilogram of honey. Unlike honey, beeswax is not a food product and is simpler to deal with - it does not require careful packaging which this simplifies storage and transport. Beeswax as an income generating resource is neglected in some areas of the tropics. Some countries of Africa where fixed comb beekeeping is still the norm, for example, Ethiopia and Angola, have significant export of beeswax, while in others the trade is neglected and beeswax is thrown away. Worldwide, many honey hunters and beekeepers do not know that beeswax can be sold or used for locally made, high-value products. Knowledge about the value of beeswax and how to process it is often lacking. It is impossible to give statistics, but maybe only half of the world’s production of beeswax comes on to the market, with the rest being thrown away and lost. WHAT BEESWAX IS Beeswax is the creamy coloured substance used by bees to build the comb that forms the structure of their nest. Very pure beeswax is white, but the presence of pollen and other substances cause it to become yellow. Beeswax is produced by all species of honeybees. Wax produced by the Asian species of honeybees is known as Ghedda wax. It differs in chemical and physical properties from the wax of Apis mellifera, and is less acidic. The waxes produced by bumblebees are very different from wax produced by honeybees. -

Drone Engorgement in Honey Beet Swarms2

Drone Engorgement in Honey Beet Swarms2 H. MICHAEL BURGETT Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14850 ABSTRACT Male Apis mel/if era L. (drones) accompanying repro- swarming. No evidenceor engorgentenl was tound. A ductive swarms were analyzed for honey stomach contentsdiurnal feeding rhythm in drones was observed in non- to determine if they engorge honey prior to or duringswarming colonies. t1\Torker honey bees, Apis melliferaL.,engorge intervals from colonies in a nonswarming cond:tion, prior to swarming (Maeterlinck1901,Garifullina starting at 0900 h and continuing until 1700 li. 1960, Combs 1972). Caront citedengorgement as To determine a niaximuni honey stomach content probably facilitatingthe processofselecting andin vivo. drones were captured just prior to afternoon settling in a new location. The object of the presentmating flight. Drones returning from mating fliglsts investigation was to determine if the drone honey bee 11150 Were sampled. could serve as a possible carrier of food reserves during swarming. RESULTS Young drones receive food from workers rather Sixty drones, 1-3 days old, reared in the laboratory, than feeding directly from colony stores. Older drones had a mean honey stomach weight of 2.0 nlg. Drones take honey from food storage cells and seldom receivesampled at 2-h intervals from coloniesina non- food from workers (Free 1957). Mindt (1962, re-swarming state had an increase in stomach content ported that drones capable of mating flights receiveduring the day, A diurnal rhythm of feeding was additional food from workers. Worker-to-drone tro- noted,Tile honey stomach weight was minimal in phallaxisis a necessary condition for drone flight the early morning (0900 h , it increased to a maxi- from swarm clusters, as I have shown (Burgett ) mum between 1230 and 1330 h, then decreasedFig, 1). -

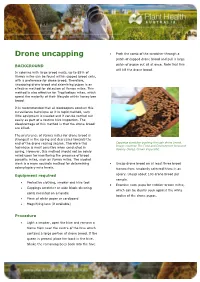

Drone Uncapping • Push the Comb of the Scratcher Through a Patch of Capped Drone Brood and Pull a Large BACKGROUND Patch of Pupae out All at Once

Drone uncapping • Push the comb of the scratcher through a patch of capped drone brood and pull a large BACKGROUND patch of pupae out all at once. Note that this will kill the drone brood. In colonies with large brood nests, up to 85% of Varroa mites can be found within capped brood cells, with a preference for drone brood. Therefore, uncapping drone brood and examining pupae is an effective method for detection of Varroa mites. This method is also effective for Tropilaelaps mites, which spend the majority of their lifecycle within honey bee brood. It is recommended that all beekeepers conduct this surveillance technique as it is rapid method, very little equipment is needed and it can be carried out easily as part of a routine hive inspection. The disadvantage of this method is that the drone brood are killed. The preference of Varroa mites for drone brood is strongest in the spring and decreases towards the end of the drone rearing season. Therefore this Cappings scratcher pushing through drone brood. Image courtesy The Food and Environment Research technique is most sensitive when conducted in Agency (Fera), Crown Copyright. spring. However, this method should not be solely relied upon for monitoring the presence of brood parasitic mites, such as Varroa mites. The alcohol wash is a more accurate method for determining • Uncap drone brood on at least three brood colony/apiary mite levels. frames from randomly selected hives in an Equipment required apiary. Uncap about 100 drone brood per sample. • Protective clothing, smoker and hive tool • Examine each pupa for reddish-brown mites, • Cappings scratcher or wide blade shearing which can be clearly seen against the white comb mounted on a handle bodies of the drone pupae. -

Flight Activity of Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera) Drones Maritza Regina Reyes, Didier Crauser, Alberto Prado, Yves Le Conte

Flight activity of honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones Maritza Regina Reyes, Didier Crauser, Alberto Prado, Yves Le Conte To cite this version: Maritza Regina Reyes, Didier Crauser, Alberto Prado, Yves Le Conte. Flight activity of honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2019, 50 (5), pp.669-680. 10.1007/s13592-019- 00677-w. hal-02282318 HAL Id: hal-02282318 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02282318 Submitted on 27 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2019) 50:669–680 Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature, 2019 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-019-00677-w Flight activity of honey bee (Apis mellifera ) drones 1 1 2 1 Maritza REYES , Didier CRAUSER , Alberto PRADO , Yves LE CONTE 1INRA, UR 406 Abeilles et Environnement, Laboratoire Biologie et Protection de l’abeille, Site Agroparc, Domaine St Paul, 84914, Avignon, France 2Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores, Unidad Juriquilla, UNAM, Querétaro, Mexico Received 18 December 2018 – Revised 24 June 2019 – Accepted5July2019 Abstract – Compared to the queen or the workers, the biology of honey bee Apis mellifera L. drones is poorly known. -

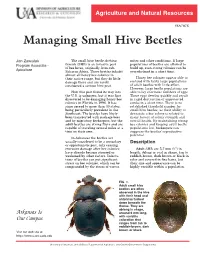

Managing Small Hive Beetles

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA7075 Managing Small Hive Beetles Jon Zawislak The small hive beetle Aethina mites and other conditions. If large Program Associate tumida (SHB) is an invasive pest popu lations of beetles are allowed to of bee hives, originally from sub- build up, even strong colonies can be Apiculture Saharan Africa. These beetles inhabit overwhelmed in a short time. almost all honey bee colonies in their native range, but they do little Honey bee colonies appear able to damage there and are rarely contend with fairly large populations considered a serious hive pest. of adult beetles with little effect. However, large beetle populations are How this pest found its way into able to lay enormous numbers of eggs. the U.S. is unknown, but it was first These eggs develop quickly and result discovered to be damaging honey bee in rapid destruction of unprotected colonies in Florida in 1998. It has combs in a short time. There is no since spread to more than 30 states, established threshold number for being particularly prevalent in the small hive beetles, as their ability to Southeast. The beetles have likely devastate a bee colony is related to been transported with package bees many factors of colony strength and and by migratory beekeepers, but the overall health. By maintaining strong adult beetles are strong fliers and are bee colonies and keeping adult beetle capable of traveling several miles at a populations low, beekeepers can time on their own. suppress the beetles’ reproductive potential. In Arkansas the beetles are usually considered to be a secondary Description or opportunistic pest, only causing 1 excessive damage after bee colonies Adult SHB are 5-7 mm ( ⁄4") in have already become stressed or length, oblong or oval in shape, tan to weakened by other factors. -

Drone Brood Removal: a Bee-Utiful Form of Varroa Control and Source of Edible Insect Protein

Drone Brood Removal: A bee-utiful form of Varroa control and source of edible insect protein Department of Environmental Studies Independent Study Thesis Bridget Gross Advisors: Dr. Susan Clayton and Dr. Carlo Moreno Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Independent Study Thesis The College of Wooster 2018 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Chapter 1: Overview: Eating Bugs and Bees? 1.1 Edible Insects…………………………………………………………………………………………………4 1.2 Honey Bees…………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 1.3 Varroa desctructor and Honey Bees……………………………………………………………….15 Chapter 2: Drone Brood Removal 2.1 Overview and Background…………………………………………………………………………….20 2.2 Research Procedure……………………………………………………………………………………...23 2.3 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………………29 2.4 Discussion……………………………………………………………………………………………………34 Chapter 3: Why the Buzz Aren’t We Eating Bees? 3.1 Overview and Background…………………………………………………………………………….40 3.2 Research Procedure……………………………………………………………………………………...45 3.3 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………………46 3.4 Discussion……………………………………………………………………………………………………52 Chapter 4: What Does This All Mean? 4.1 Review of Results………………………………………………………………………………………….58 4.2 General Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………….….59 4.3 Concluding Remarks……………………………………………………………………………………..65 Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...67 Appendix B…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...69 Literature -

The Effect of Drone Comb on a Honey Bee Colony's Production of Honey

The effect of drone comb on a honey bee colony’s production of honey Thomas Seeley To cite this version: Thomas Seeley. The effect of drone comb on a honey bee colony’s production of honey. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2002, 33 (1), pp.75-86. 10.1051/apido:2001008. hal-00891902 HAL Id: hal-00891902 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00891902 Submitted on 1 Jan 2002 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie 33 (2002) 75–86 DOI: 10.1051/apido: 2001008 75 Original article The effect of drone comb on a honey bee colony’s production of honey* Thomas D. SEELEY** Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA (Received 15 May 2001; revised 28 August 2001; accepted 16 November 2001) Abstract – This study examined the impact on a colony’s honey production of providing it with a nat- ural amount (20%) of drone comb. Over 3 summers, for the period mid May to late August, I mea- sured the weight gains of 10 colonies, 5 with drone comb and 5 without it. Colonies with drone comb gained only 25.2 ± 16.0 kg whereas those without drone comb gained 48.8 ± 14.8 kg.