Fluid-Induced Harm in the Hospital: Look Beyond Volume and Start Considering Sodium. from Physiology Towards Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pediatric Pharmacotherapy

Pediatric Pharmacotherapy A Monthly Review for Health Care Professionals of the Children's Medical Center Volume 1, Number 10, October 1995 DIURETICS IN CHILDREN • Overview • Loop Diuretics • Thiazide Diuretics • Metolazone • Potassium Sparing Diuretics • Diuretic Dosages • Efficacy of Diuretics in Chronic Pulmonary Disease • Summary • References Pharmacology Literature Reviews • Ibuprofen Overdosage • Predicting Creatinine Clearance Formulary Update Diuretics are used for a wide variety of conditions in infancy and childhood, including the management of pulmonary diseases such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)(1 -5). Both RDS and BPD are often associated with underlying pulmonary edema and clinical improvement has been documented with diuretic use.6 Diuretics also play a major role in the management of congestive heart failure (CHF), which is frequently the result of congenital heart disease (7). Other indications, include hypertension due to the presence of cardiac or renal dysfunction. Hypertension in children is often resistant to therapy, requiring the use of multidrug regimens for optimal blood pressure control (8). Control of fluid and electrolyte status in the pediatric population remains a therapeutic challenge due to the profound effects of age and development on renal function. Although diuretics have been used extensively in infants and children, few controlled studies have been conducted to define the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of diuretics in this population. Nonetheless, diuretic therapy has become an important part of the management of critically ill infants and children. This issue will review the mechanisms of action, monitoring parameters, and indications for use of diuretics in the pediatric population (1-5). Loop Diuretics Loop diuretics are the most potent of the available diuretics (4). -

Primary Structure and Functional Expression of a Cdna Encoding the Thiazide-Sensitive, Electroneutral Sodium-Chloride Cotransporter GERARDO GAMBA*, SAMUEL N

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 2749-2753, April 1993 Physiology Primary structure and functional expression of a cDNA encoding the thiazide-sensitive, electroneutral sodium-chloride cotransporter GERARDO GAMBA*, SAMUEL N. SALTZBERG*t, MICHAEL LOMBARDI*, AKIHIKO MIYANOSHITA*, JONATHAN LYTTON*, MATTHIAS A. HEDIGER*, BARRY M. BRENNER*, AND STEVEN C. HEBERT*t§ *Laboratory of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Center for Study of Kidney Disease, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; and tMount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, Salsbury Cave, ME 04672 Communicated by Robert W. Berliner, December 17, 1992 ABSTRACT Electroneutral Na+:Cl- cotransport systems et al. (15) have identified a protein band of 185 kDa obtained are involved in a number of important physiological processes from membranes of rabbit renal cortex exposed to [3H]me- including salt absorption and secretion by epithelia and cell tolazone that may be a component of the thiazide-sensitive volume regulation. One group of Na+:Cl- cotransporters is Na+:Cl- cotransporter. specifically inhibited by the benzothiadiazine (thiazide) class of In this report we describe the sequence, functional and diuretic agents and can be distinguished from Na+:K+:2ClI pharmacological characterization, and tissue-specific expres- cotransporters based on a lack of K+ requirement and insen- sion of a cDNA clone (TSCil) encoding the electroneutral sitivity to sulfamoylbenzoic acid diuretics like bumetanide. We thiazide-sensitive Na+ :C1- cotransporter, isolated by a func- report here the isolation of a cDNA encoding a thiazide- tional expression strategy from the urinary bladder of the sensitive, electroneutral sodium-chloride cotransporter from euryhaline teleost P. -

The Bumetanide-Sensitive Na-K-2Cl Cotransporter NKCC1 As a Potential Target of a Novel Mechanism-Based Treatment Strategy for Neonatal Seizures

Neurosurg Focus 25 (3):E22, 2008 The bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1 as a potential target of a novel mechanism-based treatment strategy for neonatal seizures KRISTOPHER T. KAHLE, M.D., PH.D.,1 AND KEVIN J. STALEY, M.D.2 1Department of Neurosurgery and 2Division of Pediatric Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Seizures that occur during the neonatal period do so with a greater frequency than at any other age, have profound con- sequences for cognitive and motor development, and are difficult to treat with the existing series of antiepileptic drugs. During development, ␥-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic neurotransmission undergoes a switch from excitatory to – – inhibitory due to a reversal of neuronal chloride (Cl ) gradients. The intracellular level of chloride ([Cl ]i) in immature neonatal neurons, compared with mature adult neurons, is about 20-40 mM higher due to robust activity of the chlo- ride-importing Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1, such that the binding of GABA to ligand-gated GABAA receptor- associated Cl– channels triggers Cl– efflux and depolarizing excitation. In adults, NKCC1 expression decreases and the – expression of the genetically related chloride-extruding K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 increases, lowering [Cl ]i to a level – such that activation of GABAA receptors triggers Cl influx and inhibitory hyperpolarization. The excitatory action of GABA in neonates, while playing an important role in neuronal development and synaptogenesis, accounts for the decreased seizure threshold, increased seizure propensity, and poor efficacy of GABAergic anticonvulsants in this age group. Bumetanide, a furosemide-related diuretic already used to treat volume overload in neonates, is a specific inhibitor of NKCC1 at low doses, can switch the GABA equilibrium potential of immature neurons from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing, and has recently been shown to inhibit epileptic activity in vitro and in vivo in animal models of neonatal seizures. -

Bumetanide Enhances Phenobarbital Efficacy in a Rat Model of Hypoxic Neonatal Seizures

Bumetanide Enhances Phenobarbital Efficacy in a Rat Model of Hypoxic Neonatal Seizures The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Cleary, Ryan T., Hongyu Sun, Thanhthao Huynh, Simon M. Manning, Yijun Li, Alexander Rotenberg, Delia M. Talos, et al. 2013. Bumetanide enhances phenobarbital efficacy in a rat model of hypoxic neonatal seizures. PLoS ONE 8(3): e57148. Published Version doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057148 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10658064 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Bumetanide Enhances Phenobarbital Efficacy in a Rat Model of Hypoxic Neonatal Seizures Ryan T. Cleary1, Hongyu Sun1, Thanhthao Huynh1, Simon M. Manning1,3, Yijun Li2, Alexander Rotenberg1, Delia M. Talos1, Kristopher T. Kahle5, Michele Jackson1, Sanjay N. Rakhade1, Gerard Berry2, Frances E. Jensen1,4* 1 Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, 2 Division of Genetics and Metabolism, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, 3 Division of Newborn Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, 4 Program in Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, 5 Department of Neurosurgery, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America Abstract Neonatal seizures can be refractory to conventional anticonvulsants, and this may in part be due to a developmental increase in expression of the neuronal Na+-K+-2 Cl2 cotransporter, NKCC1, and consequent paradoxical excitatory actions of GABAA receptors in the perinatal period. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 Bezwada (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US008O26285B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 BeZWada (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 27, 2011 (54) CONTROL RELEASE OF BIOLOGICALLY 6,955,827 B2 10/2005 Barabolak ACTIVE COMPOUNDS FROM 2002/0028229 A1 3/2002 Lezdey 2002fO169275 A1 11/2002 Matsuda MULT-ARMED OLGOMERS 2003/O158598 A1 8, 2003 Ashton et al. 2003/0216307 A1 11/2003 Kohn (75) Inventor: Rao S. Bezwada, Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2003/0232091 A1 12/2003 Shefer 2004/0096476 A1 5, 2004 Uhrich (73) Assignee: Bezwada Biomedical, LLC, 2004/01 17007 A1 6/2004 Whitbourne 2004/O185250 A1 9, 2004 John Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2005/0048121 A1 3, 2005 East 2005/OO74493 A1 4/2005 Mehta (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005/OO953OO A1 5/2005 Wynn patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2005, 0112171 A1 5/2005 Tang U.S.C. 154(b) by 423 days. 2005/O152958 A1 7/2005 Cordes 2005/0238689 A1 10/2005 Carpenter 2006, OO13851 A1 1/2006 Giroux (21) Appl. No.: 12/203,761 2006/0091034 A1 5, 2006 Scalzo 2006/0172983 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada (22) Filed: Sep. 3, 2008 2006,0188547 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada 2007,025 1831 A1 11/2007 Kaczur (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2009/0076174 A1 Mar. 19, 2009 EP OO99.177 1, 1984 EP 146.0089 9, 2004 Related U.S. Application Data WO WO9638528 12/1996 WO WO 2004/008101 1, 2004 (60) Provisional application No. 60/969,787, filed on Sep. WO WO 2006/052790 5, 2006 4, 2007. -

Azosemide Is More Potent Than Bumetanide and Various Other Loop

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Azosemide is more potent than bumetanide and various other loop diuretics to inhibit the sodium- Received: 21 November 2017 Accepted: 14 June 2018 potassium-chloride-cotransporter Published: xx xx xxxx human variants hNKCC1A and hNKCC1B Philip Hampel 1,2, Kerstin Römermann1, Nanna MacAulay 3 & Wolfgang Löscher1,2 The Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 plays a role in neuronal Cl− homeostasis secretion and represents a target for brain pathologies with altered NKCC1 function. Two main variants of NKCC1 have been identifed: a full-length NKCC1 transcript (NKCC1A) and a shorter splice variant (NKCC1B) that is particularly enriched in the brain. The loop diuretic bumetanide is often used to inhibit NKCC1 in brain disorders, but only poorly crosses the blood-brain barrier. We determined the sensitivity of the two human NKCC1 splice variants to bumetanide and various other chemically diverse loop diuretics, using the Xenopus oocyte heterologous expression system. Azosemide was the most potent NKCC1 inhibitor (IC50s 0.246 µM for hNKCC1A and 0.197 µM for NKCC1B), being about 4-times more potent than bumetanide. Structurally, a carboxylic group as in bumetanide was not a prerequisite for potent NKCC1 inhibition, whereas loop diuretics without a sulfonamide group were less potent. None of the drugs tested were selective for hNKCC1B vs. hNKCC1A, indicating that loop diuretics are not a useful starting point to design NKCC1B-specifc compounds. Azosemide was found to exert an unexpectedly potent inhibitory efect and as a non-acidic compound, it is more likely to cross the blood-brain barrier than bumetanide. Te Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 (encoded by SLC12A2) plays an important role in Cl- uptake in neu- rons both in developing brain and in adult sensory neurons1,2. -

Effect of Co-Adminis-Tration of Bumetanideand Phenobarbital on Seizure Attacks in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Basic and Clinical November, December 2018, Volume 9, Number 6 Research Paper: Effect of Co-administration of Bumetanide and Phenobarbital on Seizure Attacks in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Reza Rahmanzadeh1 , Soraya Mehrabi1, Mahmood Barati2, Milad Ahmadi3, Fereshteh Golab1* , Sareh Kazmi1, Mohammad Taghi Joghataei1,4* , Morteza Seifi5, Mazaher Gholipourmalekabadi6 1. Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 2. Department of Biotechnology, School of Allied Medicine, Iran University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran. 3. Shefa Neuroscience Research Center, Tehran, Iran. 4. Department of Anatomy, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 5. Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. 6. Department of Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Use your device to scan and read the article online Citation: Rahmanzadeh, R., Mehrabi, S., Barati, M., Ahmadi, M., Golab, F., Kazmi, S., et al. (2018). Effect of Co-adminis- tration of Bumetanideand Phenobarbital on Seizure Attacks in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 9(6), 408-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/bcn.9.6.408 : http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/bcn.9.6.408 A B S T R A C T Funding: See Page 414 Introduction: The resistance of temporal lobe epilepsy to classic drugs is thought to be due to disruption in the excitation/inhibition of this pathway. Two chloride transporters, NKCC1 Article info: and KCC2, are expressed differently for the excitatory state of Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid Received: 11 September 2016 (GABA). -

Package Leaflet: Information for the Patient Bumetanide 1 Mg and 5 Mg Tablets (Bumetanide) Read All of This Leaflet Carefully Be

Package leaflet: Information for the patient Bumetanide 1 mg and 5 mg Tablets (bumetanide) Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet: 1. What Bumetanide is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Bumetanide 3. How to take Bumetanide 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Bumetanide 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Bumetanide is and what it is used for Bumetanide belongs to a group of medicines called diuretics (or ‘water’ tablets). Diuretics act on the kidneys to increase the flow of urine. This gets rid of excess water from your body and reduces the effect of water build up. Bumetanide can be used to help get rid of excess water in your body, which may be caused by medical problems such as heart failure, liver or kidney disease. 2. What you need to know before you take Bumetanide Do not take Bumetanide if you: are allergic to bumetanide, sulfonamide medicines (which may include some medicines used to treat infections e.g. -

Review Course Lectures

Review Course Lectures International Anesthesia Research Society IARS 2011 REVIEW COURSE LECTURES The material included in the publication has not undergone peer review or review by the Editorial Board of Anesthesia and Analgesia for this publication. Any of the material in this publication may have been transmitted by the author to IARS in various forms of electronic medium. IARS has used its best efforts to receive and format electronic submissions for this publication but has not reviewed each abstract for the purpose of textual error correction and is not liable in any way for any formatting, textual, or grammatical error or inaccuracy. 2 ©2011 International Anesthesia Research Society. Unauthorized Use Prohibited IARS 2011 REVIEW COURSE LECTURES Table of Contents Perioperative Implications of Emerging Concepts In Management of the Malignant Hyperthermia Vascular Aging, Health And Disease Patient In Ambulatory Surgery Charles W. Hogue, MD ..............................1 Denise J. Wedel, MD ...............................38 Professor of Anesthesiology and Professor of Anesthesiology, Mayo Clinic Critical Care Medicine Rochester, Minnesota Chief, Division of Adult Anesthesia The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Central Venous Access Guideline The Johns Hopkins Hospital Development and Recommendations Baltimore, Maryland Stephen M. Rupp, MD ..............................41 Anesthesiologist Perioperative Management of Pain and PONV in Medical Director, Perioperative Services Ambulatory Surgery Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, Washington Spencer S. Liu, MD .................................5 Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology Pediatric Anesthesia and Analgesia Outside the OR: Director of Acute Pain Service What You Need To Know Hospital for Special Surgery Pierre Fiset, MD, FRCPC............................47 New York, New York Department Head, Anesthesiology Montreal Children’s Hospital Colloid or Crystalloid: Any Differences In Outcomes? Montreal, Quebec, Canada Tong J. -

Presented By: Dr. Joohee Pradhan Assistant Professor Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, MLSU, Udaipur

Presented By: Dr. Joohee Pradhan Assistant Professor Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, MLSU, Udaipur OUTLINE • Introduction and Definition • Relevant Physiology of Urine Formation • Classification: different ways • Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Acetazolamide*, Methazolamide, Dichlorphenamide. • Thiazides: Chlorthiazide*, Hydrochlorothiazide, Hydroflumethiazide, Cyclothiazide, • Loop diuretics: Furosemide*, Bumetanide, Ethacrynic acid. • Potassium sparing Diuretics: Spironolactone, Triamterene, Amiloride. • Osmotic Diuretics: Mannitol 2 Introduction and Definition • Diuretics (natriuretics) are drugs which cause a net loss of Na+ and water in urine and hence increase the urine output (or) urine volume. • The primary action of most diuretics is the direct inhibition of Na+ reabsorption (increased excretion) at one or more of the four major sites along the nephron. • An increased Na+ excretion is accompanied by anion like Cl- Since NaCl is the major determinant of extracellular fluid volume; Diuretics reduce extracellular fluid volume (decrease in oedema) by decreasing total body NaCl content. 3 Introduction and Definition • Diuretics are very effective in the treatment of conditions like: o chronic heart failure o nephrotic syndrome o chronic hepatic diseases o hypertension o Pregnancy associated oedema o Cirrhosis of the liver. 4 Relevant Physiology of Urine Formation • Kidneys are the organs responsible for urine formation. Two important functions of the kidney are: o To maintain a homeostatis balance of electrolytes and water. o To excrete water soluble end products of metabolites. • Each kidney contains approximately one million nephrons and is capable of forming urine independently. • Urine formation starts from glomerular filtration (g.f.) in a prodigal way. • Normally, about 180 L of fluid is filtered everyday: all soluble constituents of blood minus the plasma proteins (along with substances bound to them) and lipids, are filtered at the glomerulus. -

2019 Prohibited List

THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE INTERNATIONAL STANDARD PROHIBITED LIST JANUARY 2019 The official text of the Prohibited List shall be maintained by WADA and shall be published in English and French. In the event of any conflict between the English and French versions, the English version shall prevail. This List shall come into effect on 1 January 2019 SUBSTANCES & METHODS PROHIBITED AT ALL TIMES (IN- AND OUT-OF-COMPETITION) IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 4.2.2 OF THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE, ALL PROHIBITED SUBSTANCES SHALL BE CONSIDERED AS “SPECIFIED SUBSTANCES” EXCEPT SUBSTANCES IN CLASSES S1, S2, S4.4, S4.5, S6.A, AND PROHIBITED METHODS M1, M2 AND M3. PROHIBITED SUBSTANCES NON-APPROVED SUBSTANCES Mestanolone; S0 Mesterolone; Any pharmacological substance which is not Metandienone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylandrosta-1,4-dien- addressed by any of the subsequent sections of the 3-one); List and with no current approval by any governmental Metenolone; regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use Methandriol; (e.g. drugs under pre-clinical or clinical development Methasterone (17β-hydroxy-2α,17α-dimethyl-5α- or discontinued, designer drugs, substances approved androstan-3-one); only for veterinary use) is prohibited at all times. Methyldienolone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylestra-4,9-dien- 3-one); ANABOLIC AGENTS Methyl-1-testosterone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methyl-5α- S1 androst-1-en-3-one); Anabolic agents are prohibited. Methylnortestosterone (17β-hydroxy-17α-methylestr-4-en- 3-one); 1. ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROIDS (AAS) Methyltestosterone; a. Exogenous* -

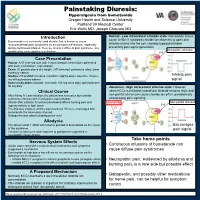

Introduction • Continuous Infusions of Bumetanide Can Cause Diffuse Pain Syndromes • Neuropathic Pain, Evidenced by Allodyni

Painstaking Diuresis: Hyperalgesia from bumetanide Oregon Health and Science University Portland VA Medical Center Erik Wells MD, Joseph Chiovaro MD Introduction • Normal - Low intracellular chloride state: Non-painful stimuli cause GABA-A mediated chloride ion channels to open and • Bumetanide is a commonly used diuretic that is known to cause musculoskeletal pain syndromes by an unknown mechanism, especially chloride rushes into the cell, causing hyperpolarization during continuous infusion. Here we review a different pain syndrome, one preventing pain signal generation Non-painful stimulus mediated by a neuropathic mechanism. (+) Case Presentation • Patient: A 57-year-old man with chronic diastolic heart failure presented with acute heart failure exacerbation • Exam: 30 pounds above dry weight, JVP elevated, pulmonary rales, lower extremity edema • Studies: NT-proBNP elevated, creatinine slightly above baseline, chest x- Inhibits pain ray with pulmonary edema signal • Home medications include: torsemide 100 mg twice daily, spironolactone 50 mg daily • Abnormal - High intracellular chloride state: However, Clinical Course when KCC2 is inhibited intracellular chloride remains high, and • After failing IV Lasix infusion, the patient was started on bumetanide non-painful stimuli can cause chloride ion efflux, paradoxically continuous infusion with metolazone augmentation. encouraging pain signaling • Shortly after initiation the patient developed diffuse burning pain and bumetanide Non-painful stimulus hypersensitivity to light touch (+)