Burma OGN V 8.0 July 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report (The UK Government's Response to the Myanmar Crisis)

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The UK Government’s Response to the Myanmar Crisis Fourth Report of Session 2021–22 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 July 2021 HC 203 Published on 16 July 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Tom Tugendhat MP (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) (Chair) Chris Bryant MP (Labour, Rhondda) Neil Coyle MP (Labour, Bermondsey and Old Southwark) Alicia Kearns MP (Conservative, Rutland and Melton) Stewart Malcolm McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow South) Andrew Rosindell MP (Conservative, Romford) Bob Seely MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Henry Smith MP (Conservative, Crawley) Royston Smith MP (Conservative, Southampton, Itchen) Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Blackley and Broughton) Claudia Webbe MP (Independent, Leicester East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Burma:Badly Battered but Believing

oneonone Burma: Badly Battered but Believing Interview by Nina Somera Silent and Steady Witness. Long-time free Burma campaigner Debbie Stothard talks about the fear, Said to be built in the 6th century, the Shwedagon suffering and frustration of the Burmese people who have endured the Pagoda has not only been a religious and cultural landmark, excesses of the junta regime. She tells us how Burmese women and their but also the stage for political movements in Burma communities remain courageous and hopeful for better days, for freedom. especially at the turn of the 20th century. It has hosted protests by students and Interview by Nina Somera workers. It was also the site where Aung San Suu Kyi delivered an address to 5,000 How would you describe the sense of In rural Burma, for example, millions have people and called for the end fear in Burma? of the military regime back in been denied the right to grow food to feed 1988. The Shwedagon Most people from Burma constantly have themselves. They have been forced to grow Pagoda was again filled with to struggle with fear of some sort. There is cash crops for the military. They may have jubilation and later tension with a great sense of insecurity. No matter what been subjected into forced labour or the the monks-led Saffron they have accumulated in their lives, material regime simply confiscated their lands and Revolution in 2007. gave them to others or declare the areas as Photo by Jean-Marie Hullot from security is constantly at threat. -

F-Burma News

BURMA CAMPAIGN NEWS www.burmacampaign.org.uk WINTER 2005 ISSUE 10 Shop at amazon.co.uk and earn money for The Burma Campaign! Buy any item at amazon.co.uk via our website Shop + and The Burma Campaign will receive a percentage of what you pay. Earn Through their Associates Programme, amazon.co.uk pays a cash commission for any sales they receive from the links on our website. So whenever you need any books, music, films, games or gifts, remember to visit www.burmacampaign.org.uk first and enter amazon.co.uk from the link on our website. Visit www.burmacampaign.org.uk/merchandise.html Did you know that you could raise money for us while talking on the phone? And cut your phone bill Five good reasons to choose the Phone Co-op: We have joined up with the Phone Co-op to offer you a great deal on your telephone calls. By using the Phone Co-op, you 1. More than just calls: Broadband from save money, and help us to raise funds, as we receive 6% of £18.99 and line rentals are also available. the value of your calls. 2. Easy to set up: It’s easy to switch and you keep your BT or cable line. That is 60p for every £10 you spend. 3. Easy to access: Call their customer service and you’ll immediately have a With four different options, we guarantee you will find the ‘real person’ on the line. most convenient one for you! You can save up to 48% on 4. -

LAST MONTH in BURMA JAN News from and About Burma 2009

LAST MONTH IN BURMA JAN News from and about Burma 2009 Rohingya refugees forced out to sea by Thai authorities The Thai government faced international condemnation after reports that Thai authorities forcibly expelled Rohingya boat people, towing them out to sea and setting them adrift. Around 1000 Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers, fleeing persecution in Burma and squalid living conditions in Bangladesh, were intercepted by the Thai navy in December 2008. They were subsequently towed into international waters in boats without engines and with little food and water. Hundreds are feared drowned, others were rescued off the coast of India and Indonesia, some claiming to have been beaten by Thai soldiers. The Rohingya are a mainly Muslim ethnic Rohingya refugees apprehended by the Thai authorities. group in western Burma. They are subjected to (Photo: Royal Thai Navy) systematic, persistent and widespread human rights violations by the ruling military regime, including denial of citizenship rights, severe restrictions of freedom of movement and arbitrary arrests. Ethnic groups reject 2010 elections of civilian government.” The Minister also stated The Kachin Independence Organization and the that; “We will continue to give our full support to the Kachin National Organization have stated they will UN Secretary General and his efforts to break the not take part in the 2010 elections. Colonel Lamang current deadlock.” Brang Seng, a spokesperson for the KNO, told Mizzima News, “We don’t think the election will be “The 2010 elections could be the freest and fairest free and fair,” and added that the elections and the in the world, but it would make little difference as junta’s roadmap are designed to further entrench the constitution they bring in keeps the dictatorship military rule in Burma. -

BUSINESS Climate Change Battle

INFLATION FEARS | Page 2 Asian markets down over Fed signal, China tech crackdown Friday, July 9, 2021 Dhul-Qa’da 29, 1442 AH GREEN LEAD : Page 4 GULF TIMES European Central Bank adds its clout to BUSINESS climate change battle Mekdam Holding Al-Kuwari meets visiting US delegation all set to join QSE venture market By Santhosh V Perumal sidiaries are Mekdam Technology, Me- The QEVM is aimed at small and me- Business Reporter kdam Technical Services and Mekdam dium sized family and private compa- Cams – generated revenues of QR168.7mn nies and provides them with an access to and Ebitda, or earnings before interest, capital market and enables them diversify he Qatar Stock Exchange (QSE) taxes, depreciation and amortisation, of their source of fi nancing, achieve the sus- yesterday said all the procedures QR26.8mn in 2020. tainability, growth and expansion. Thave been completed for the listing Mekdam Technology accounted for The companies eligible to join the of Mekdam Holding Group, which will be 55% of 2020 group revenue and 42% of QEVM should have an issued capital not the second entity to get listed on the ven- Ebitda; Mekdam Technical Services (28% below QR2mn, and number of sharehold- ture market or QEVM. and 24%) and Mekdam Cams (8% and ers not less than 20 who own no less than HE the Minister of Commerce and Industry and Acting Minister of Finance Ali bin Ahmed al-Kuwari met “Co-ordination is currently taking 28%). 10% of its capital upon the listing. yesterday with a high-level delegation from the American State of Indiana headed by its Governor Eric place between the QSE and the Qatar Fi- “The company benefi ts from strong The new market is the result of the stra- J Holcomb, who is currently visiting the country. -

From Pariah to Partner: the US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015

INDIA BHUTAN CHINA BAN GLADESH VIETNAM Naypidaw Chiang Mai LAOS Rangoon THAILAND Bangkok CAMBODIA From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 From Pariah to Partner The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma Making Peace Possible 2009 to 2015 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. -

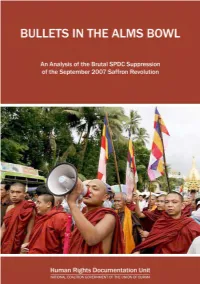

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

President U Win Myint Accepts Credentials from Ireland Ambassador

SELF-CARE IS BETTER THAN CURE PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister U Thaung Tun attends Fighting between Tatmadaw troops, AA 55th Munich Security Conference insurgents occurred on 19 February PAGE-4 PAGE-14 Vol. V, No. 310, 1st Waning of Tabodwe 1380 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Wednesday, 20 February 2019 It is a matter of pride for the Union The rays of peace are shinning in that we held a national-level political Mon State, giving warmth to the dialogue with Chin Reps. people in the state Message of Greetings sent by President U Win Myint to Message of Greetings from the State Counsellor the 71st Anniversary Celebrations of Chin National Day to 72nd Anniversary celebrations of Mon National Day Dear esteemed brothers and sisters of Chin ethnic people, Today, 20 February, 2019, the 1st of Waning of Tabodwe, 1380 ME, is the Mon On this auspicious day, the 20th February 2019, which is the 71st Anniversary National Day, an auspicious day for all Mon ethnic people. On this auspicious of Chin National Day, I wish to send my Message of Greetings to all Chin ethnic day, I am sending my message of greetings to all Mon ethnic people who are people who are living in Chin State, other parts of Myanmar and abroad, to be living in parts of Myanmar and abroad. May they be blessed with fortune and blessed with good fortune and auspiciousness. auspiciousness. After annexing entire Myanmar in 1885, the British colonialists practiced the The day - the 1st Waning of Tabodwe, 1116 Sasana Era - when two brothers, divide and rule policy between the hilly regions and plain regions of the country. -

Burma Briefing No 4 – the European Union on the EU Still Has Economic Muscle Than Can and Burma

Burma Germany & Burma: Business before Briefing human rights No. 13 June 2011 Commentary by Burma Campaign UK On 20th June 2011 the Financial Times published human rights abuses makes relaxing pressure No. 1 an article by Markus Loening, Germany’s federal on the dictatorship sound less reasonable. It is, July 2010 commissioner for human rights policy, ‘It is time therefore, no surprise that they get only a passing to fine-tune sanctions on Burma’. It is rare for a mention. Also downplayed are the rigged elections German government official to make a detailed last November, described merely as ‘flawed’. The statement on their thinking on Burma policy, and the decades long crisis of internal displacement and article is more revealing than perhaps was intended. refugees, affecting millions of people, is bizarrely described as only ‘brewing’. Loening’s arguments expose a fundamental misunderstanding of the situation in Burma, the Loening argues that sanctions must be ‘fine-tuned, history of EU policy, of the Burmese economy, and linked to performance, and lifted, stage by stage, to of the dictatorship itself. This misunderstanding reward progress.’ This is not new, it has technically is shared by his government and several other been EU policy since the first Common Position EU members. The article also contains many was agreed back in 1996. It is Germany that has inaccuracies. been one of the main obstacles to implementing this policy. In his first sentence Loening, who is unknown to most Europeans, describes himself as the first high- EU Burma policy once made sense. Sanctions ranking European to visit Burma since the elections, would be gradually increased if there was no despite officials from many European countries progress towards improving human rights and having already visited. -

Supporting Democratic and Peaceful Change in Burma/Myanmar

Supporting Democratic and Peaceful Change in Burma/Myanmar Timo Kivimäki, Kristiina Rintakoski, Sami Lahdensuo and Dene Cairns CRISIS MANAGEMENT INITIATIVE REPORT OCTOBER 2010 Language editing: Mikko Patokallio Graphic design: Ossi Gustafsson, Hiekka Graphics Layout: Saila Huusko, Crisis Management Initiative Crisis Management Initiative Eteläranta 12 00130 Helsinki Finland www.cmi.fi ABOUT THE CRISIS MANAGEMENT INITIATIVE Crisis Management Initiative, a Finnish independent non-profit organization, works to resolve conflict and to build sustainable peace by engaging people and communities affected by violence. CMI was founded in 2000 by its Chairman President Martti Ahtisaari. The headquarters of the organisation are in Helsinki, Finland. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Crisis Management Initiative is grateful for the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland for financial support to this project. This report is the outcome of insights, expertise and experience contributed by a number of individuals. The authors would particularly like to thank all individuals interviewed for this report in Yangon and in the region in August 2010 and in earlier occasions. The authors would also like to express their appreciation to Mikko Patokallio for very skilful language editing and for Saila Huusko for her assistance in the processing of this document. 1 INTRODUCTION On November 7, 2010, Burma/Myanmar1 will organize its first parliamentary elections since 1990. The significance of the elections stems from the controversial constitution on which they are based and which involves a complete reconfiguration of the political structure. It establishes a presidential system of government with a bicameral legislature as well as fourteen regional governments and assemblies – the most wide-ranging change in a generation. -

UPDATE: Following a High Profile Campaign, BAT Pulled out of Burma in November 2003

UPDATE: Following a high profile campaign, BAT pulled out of Burma in November 2003 Campaign Report November 2002 Contents ‐ Executive Summary ‐ Background ‐ The Dictatorship in Burma ‐ The Disinvestment Campaign ‐ Background on BAT's investment in Burma ‐ About BAT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BAT is one of the most important UK investors in Burma. Its Burmese subsidiary – Rothmans of Pall Mall Myanmar – is a joint venture with Burma’s military regime; a regime described by the US State Department as brutal, repressive, and routinely using torture. 1 The facts in brief: • BAT’s factory in Burma is a joint venture with the military regime. • The industrial zone where BAT has its factory was upgraded by the military authorities using child labour. • BAT pays its factory workers around 23p a day. • Ken Clarke QC MP, Deputy Chairman of BAT, has said he is “uncomfortable’ with companies investing in Burma. • Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s democracy leader, has asked companies not to invest in Burma. • It would take 85 years (three generations) for one of BAT’s factory workers in Burma to earn what BAT Chairman Martin Broughton earns in a single day. 2 • By investing in Burma BAT is collaborating with a regime that routinely uses rape and torture to suppress its own people. • The regime in Burma spends just 44p per person per year on health and education combined. • BAT makes a profit of £5,136 a minute. It would take just 6 minutes worth of BAT’s annual profits to give its workers in Burma a years salary as severance pay.