Walter-Scott-The-Fortunes-Of-Nigel.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Catalogue of Impressions from Ancient Scottish Seals ... From

5es. Sc^j •A. Z? V^//*^ jLa*/jfy sf ^Jjfam^* / «? ^/V>7-. /7z^ 's^^ty^ -- y '^ / / *'^ / 7 - *RotaOetotitomif Oftnlv fM Ctdw zamckwrfcan IdtiSftQ ucImuc l)Acm«a"pfcttr| C1IX7I COmfirnuac cfaiu j VWuftc c 6cSc-HCOttifiinjMiirr,So i fee <\£l£)C i y^H ma a 1 tnoindnf W €rc ^o lpfi ^ mibie Crrmcft? emmedf . 1 itvdrof VitmStttt! ^ j^^TtitHd^ca rcU^inTrtrtx <^<faaceruffy ^tarcftreV^i J ftc uu tefomWinoMico *fut& tfzian* uia; tttCTSzmrcr .])CC on?U ICOticc(tiMbcbi^Ctlt»re <&£ nice. M v attuta djeme pjcrm ma tnec c pyj «ttltM^ yarf m tuxcf i oimmn |«miru tne^.Jfflf - y DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGUE IMPRESSIONS FROM ANCIENT SCOTTISH SEALS, lloiial, aSaromal, ©cdcsiastical, anO itUmtcipal, EMBRACING A PERU)]) FROM A.D. 109-1 TO THE COMMONWEALTH. TAKEN EROM ORIGINAL CHARTERS AND OTHER DEEDS PRESERVED IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ARCHIVES. BY HENRY IAIKG, EDINBURGH. EDINBURGH—MDCCCL. (INLY ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY COPIES PRINTED FOR SALE. EUINUUHGI1 : I. CUNM.Wil.E, PIllXlliK lu I1LK MAJBSTV. TO THE PRESIDENTS AND MEMBERS OF THE BANNATYtfE AND MAITIAND CLUBS AND TO ITS OTHER SUPPORTERS THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY HENRY LAING. LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS.' His Royal Highness Prince Albert. The Earl of Aberdeen. Dr. "Walter Adam, Edinburgh. Archaeological Association of London. The Duke of Buccleuch and Qdeensberry. Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, of Brisbane, Bart. The Hon. George Frederick Boyle. Charles Baxter, Esq., Edinburgh. Henry B. Beaufoy, Esq., South Lambeth. John Bell, Esq., Dungannon. Miss Bicknell, Fryars, Beaumaris. W. H. Blaauw, Esq., London. Rev. Dr. Bliss, Principal of St Mary's Hall, Oxford. Rev. Dr. Bloxam, S. -

The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate

Finlay, J. (2004) The early career of Thomas Craig, advocate. Edinburgh Law Review, 8 (3). pp. 298-328. ISSN 1364-9809 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/37849/ Deposited on: 02 April 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk EdinLR Vol 8 pp 298-328 The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate John Finlay* Analysis of the clients of the advocate and jurist Thomas Craig of Riccarton in a formative period of his practice as an advocate can be valuable in demonstrating the dynamics of a career that was to be noteworthy not only in Scottish but in international terms. However, it raises the question of whether Craig’s undoubted reputation as a writer has led to a misleading assessment of his prominence as an advocate in the legal profession of his day. A. INTRODUCTION Thomas Craig (c 1538–1608) is best known to posterity as the author of Jus Feudale and as a commissioner appointed by James VI in 1604 to discuss the possi- bility of a union of laws between England and Scotland.1 Following from the latter enterprise, he was the author of De Hominio (published in 1695 as Scotland”s * Lecturer in Law, University of Glasgow. The research required to complete this article was made possible by an award under the research leave scheme of the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the author is very grateful for this support. He also wishes to thank Dr Sharon Adams, Mr John H Ballantyne, Dr Julian Goodare and Mr W D H Sellar for comments on drafts of this article, the anonymous reviewer for the Edinburgh Law Review, and also the members of the Scottish Legal History Group to whom an early version of this paper was presented in October 2003. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

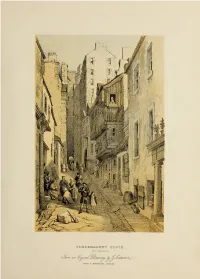

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Collections and Notes Historical and Genealogical Regarding the Heriots of Trabroun, Scotland

.:.v^' y National Library of Scotland 'B000264462* — — COLLECTIONS AND NOTES HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL REGARDING THE HERIOTS OF TRABROUN, SCOTLAND. COMPILED PROM AUTHENTIC SOURCES By G. W. B., AND REPRINTED FROM THE SUPPLEMENT TO THIRD EDITION OF HISTORY OF HERIOT'S HOSPITAL. " "What is thy country? and of what people art thou ? Jonah, I. 8. ' ' Rely upon it, the man who does not worthily estimate his own dead forefathers will himself do very little to add credit or honour to his country." Gladstone. PRINTED FOR PRIVA^CIRCULATIQN. 1878. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/collectionsnotesOOball NOTE. The following pages are the result of a search made chiefly among old records in Edinburgh. The Compiler regrets that circumstances have prevented him continuing his investigations and endeavouring to make the Collections and Notes as complete as he wished. His thanks are due to J. Ronaldson Lyell, Esq., Lochy Bank, Auchtermuchty, Mr G. Heriot Stevens, Gullane, and Mr Eobb, Manager, Gas Works, Haddington, for the information they severally and kindly communicated. Further information will he thankfully received by the Compiler Mr Gr. W. B., per Messrs Ogle & Murray, 49 South Bridge, Edinburgh. EXPLANATION OF ABBREVIATIONS A. D. A., Acta Dominorum Auditorum. A. D. C, Acta Dominorum Concilii. P. C. T., Pitcairn's Criminal Trials. E. of D., Register of Deeds. R. of P. C, Register of Privy Council. R. of P. S., Register of Privy Seal. R. of R., Register of Retours. a" INTRODUCTION. The derivation of the word " Heriot " is given— in Jamieson's Scottish Dictionary (Longmnir's edition) thus : " Heriot : The fine exacted by a superior on the death of his tenant. -

The Transformation of Edinburgh Land,Property and Trust in the Nineteenth Century

The Transformation of Edinburgh Land,Property and Trust in the Nineteenth Century Richard Rodger University of Leicester The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York,NY 10011-4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, VIC 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa © Richard Rodger 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Plantin 10/12 System QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Rodger, Richard. The transformation of Edinburgh: land, property and trust in the nineteenth century / Richard Rodger. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 78024 1 1. Edinburgh (Scotland) – Social conditions. 2. Urbanization – Scotland – Edinburgh. 3. Housing – Scotland – Edinburgh – History – 19th century. 4. Edinburgh (Scotland) – History. I. Title: The transformation of Edinburgh. II. Title. HN398.E27 R63 2000 306Ј.09413Ј4–dc21 00–040347 ISBN 0 521 78024 1 hardback Contents List of figures page vii List of tables xii Acknowledgements xv List of abbreviations -

Ebook Download Burial of Ghosts Pdf Free Download

BURIAL OF GHOSTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ann Cleeves | 352 pages | 12 Sep 2013 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447241300 | English | London, United Kingdom Burial of Ghosts PDF Book Not a collision of passion and death to me? Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? Robert Galbraith. Cultures all around the world believe in spirits that survive death to live in another realm. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. The Foundling. Reit, 83, a Creator of Casper the Friendly Ghost". Psychopomps , deities of the underworld , and resurrection deities are commonly called death deities in religious texts. The idea that the dead remain with us in spirit is an ancient one, appearing in countless stories, from the Bible to "Macbeth. South Africa. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced, brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Everyone should read her Shetland Island series! Your review has been submitted successfully. November Learn how and when to remove this template message. In the days that follow, she is distracted by thoughts of her mysterious lover, hoping against hope that Philip might come and find her. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Kadokawa Gakugei Shuppan. After a brief affair, Lizzie returns to England. About this product. Berkeley: University of California Press. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Most people who believe in ghosts do so because of some personal experience; they grew up in a home where the existence of friendly spirits was taken for granted, for example, or they had some unnerving experience on a ghost tour or local haunt. -

Burial of Ghosts Free

FREE BURIAL OF GHOSTS PDF Ann Cleeves | 352 pages | 12 Sep 2013 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447241300 | English | London, United Kingdom Burial of Ghosts by Ann Cleeves | Waterstones If you believe in ghosts, you're not alone. Cultures all around the world believe in spirits Burial of Ghosts survive death to live in another realm. The idea that the dead remain with us in spirit is an ancient one, appearing in countless stories, from the Bible to "Macbeth. Belief in ghosts is part of a larger web of related paranormal beliefs, including near-death experience, life after death, and spirit Burial of Ghosts. The belief offers many people comfort — who doesn't want to believe that our beloved but deceased family members aren't looking out for us, or with us in our times of need? Ghost clubs dedicated to searching for ghostly evidence formed at prestigious universities, including Cambridge and Oxford, and in the most prominent organization, the Society for Psychical Research, was established. A woman Burial of Ghosts Eleanor Sidgwick was an investigator and later president of that group, and could be considered the original female ghostbuster. In America during the late s, many psychic mediums claimed to speak to the dead — but were later exposed as frauds by skeptical investigators such as Harry Houdini. It wasn't until Burial of Ghosts that ghost hunting became a widespread interest around the world. Much of this is due to the hit Syfy cable TV series "Ghost Hunters," now in its second decade of not finding good evidence for ghosts. The show spawned dozens of spinoffs and imitators, and it's not hard to see why the show is so popular: the premise is that anyone can look for ghosts. -

Isla Woodman Phd Thesis

EDUCATION AND EPISCOPACY: THE UNIVERSITIES OF SCOTLAND IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY Isla Woodman A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1882 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License Education and Episcopacy: the Universities of Scotland in the Fifteenth Century by Isla Woodman Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Scottish Historical Research School of History University of St Andrews September 2010 Declarations 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Isla Woodman, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2004 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in June 2005; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2004 and 2010. Date ……………………… Signature of candidate ……………………………….. 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Being a Series of Views of Edinburgh and Its Environs

WILTS S IMA1KET €jL© S IE EDINBURGH Qjyumi/ an- (^t^na^ _I^W^£- ~&r&ai fy- JOHN G MURDOCH . LONDON ' ; EDINBURGH: THE OLD CITY. 101 beneath were six tables extending to the north end of the hall. The company included all the nobility and gentlemen of distinction then in Edinburgh, the officers of state, the judges, the law advisers of the crown, and a great many naval and military officers. On this occasion the King first announced to the Lord Provost his elevation to the baronetage, when he drank to " Sir William Arbuthnot, Baronet, and the Corporation of the City of Edinburgh." Such is an outline of the history of the Parliament House at Edinburgh, interesting on account of its past and present associations. 1 When the many distinguished men are recollected, the ornaments of the bench, the bar, and of literature, who have professionally walked and still tread its beautiful oak floor during the sittings of the Supreme Court, it will ever remain an object of peculiar importance in the Scottish metropolis. THE CROSS. " Ddn-Edin's Cross," the demolition of which elicited a " minstrel's malison " from Sir Walter Scott,2 was a " pillared stone " of some antiquity, upwards of twenty feet high and eighteen inches diameter, sculptured with thistles, and surmounted by a Corinthian capital, on the top of which was an unicorn. This pillar rose from an octagonal building of sixteen feet diameter and about fifteen feet high, at each angle of which was an Ionic pillar supporting a kind of projecting Gothic bastion, and between those columns were arches. -

Amityville Horror, the 23

A the shape of an awe-inspiring agency of guilt, Abjection the repressed fi gure of maternal authority ELISABETH BRONFEN returns either as an embodiment of the Holy Mary’s sublime femininity or as a monstrous As an adjective, “abject” qualifi es contemptible body of procreation, out to devour us and actions (such as cowardice), wretched emo- transform us into the site for further grotesque tional states (such as grief or poverty), and self- breeding. By drawing attention to the manner abasing attitudes (such as apologies). Derived in which a cultural fear regarding the uncon- from the Latin past participle of abicere, the trollability of feminine reproduction has con- word has come into use within Gothic studies sistently served as a source of horror, abjection primarily to discuss processes by which some- has proven a particularly resonant term for a thing or someone belonging to the domain of study of Gothic culture. the degrading, miserable, or extremely submis- The abject is not to be thought of as a static sive is cast off. Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror concept, pertaining to something monstrous (1982) fi rst introduced abjection as a critical or unclean per se. Instead, it speaks to a thresh- term. Picking up on the anthropological study old situation, both horrifying and fascinating. of initiation rites discussed by Mary Douglas in It involves a tripartite process in the course of her book Purity and Danger (1966), Kristeva which forces that threaten stable identities addresses the acts of separation necessary for come again to be contained. For one, abjection setting up and preserving social identity. -

Supplement to Third Edition of History of George Heriot's Hospital : And

^^J**'''-vM£ekV. *ft " 4 i®& ^ ' National Library of Scotland *B000061252* c < "< -/f6/£ - c - ' c * / ^# ^: ,H s s *v*. * * -^ r >l 0NA£ . N '-. X "^009 >° Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/supplementtothir1878bedf SUPPLEMENT TO THIRD EDI HISTOEY OF GEORGE HERIOT'S HOSPITAL, AND THE HERIOT FOUNDATION SCHOOLS, FEEDEEICK W. BEDFOED, LL.D., HOTJSE-GOVEENOB AND HEAD-MASTEK OP HEEIOT's HOSPITAL, AND INSPEOTOB OP HEBIOT FOUNDATION SCHOOLS. EDINBURGH: BELL & BRADFUTE, 12 BANK STREET. 1878. %1957^ PREFACE TO SUPPLEMENT TO THE THIRD EDITION. rilHE latest (Third) Edition of the History of Heriot's Hospital was published in July 1872. As the sale of this Book is limited principally to persons connected with the Institution, it requires several years to exhaust a moderately-sized Edition. Thirteen years elapsed between the Second and Third Editions. As the Text and Appen- dixes are frequently found by the Governors and Officials convenient for purposes of reference, the Editor has thought its usefulness will be much increased, if, between the issue of two Editions, a small Supplement be published contain- ing a brief record of the principal events in the History of the Hospital since the publication of the previous Edition, so that the Book may never be more than a few years out of date. The present Supplementary pages have been pre- pared with this view. Since 1872, six Out-door Schools (Three Juvenile and Three Infant) have been erected, and one temporarily established in the Fountainbridge District ; Free Evening Classes have been formed for the instruction of Males and Females during the Winter Months; the important Bur- 4 PREFACE.