TALES from the CRYPT: and Other Stories from Copyright’S Past Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enews 170430

5/1/2017 Print Subject: Fwd: JLS Middle School PTA Newsletter From: Scott Thomas ([email protected]) To: [email protected]; Date: Sunday, April 30, 2017 10:08 PM Scott (650) 4400928 cell Begin forwarded message: From: JLS eNews Editor <[email protected]> Date: April 30, 2017 at 1:50:54 AM PDT To: [email protected] Subject: JLS Middle School PTA Newsletter ReplyTo: [email protected] PANTHER TRACKS - JLS PTA eNews Sun, April 30 Dear Scott MARK YOUR CALENDAR Staff Appreciation Week May 1 5 7th grade CAASPP testing May 1 4 about:blank 1/13 5/1/2017 Print Project Linus Donations May 1 5 8th grade Science CAST Tue May 2 JLS Choir singing at Stanford baseball game Tue May 2, 5 6PM, Klein Field at Sunken Diamond Many Faces of JLS/Open House Wed May 3, 5:30 8PM PTA Latte Cart for Staff Thu May 4, 7:30 10:30AM Student Store open Fri May 5, 12:30PM Staff Appreciation Week! May 15 The PTA will be celebrating our teachers and staff all week long with lunch and latte carts and so much more! Feel free to send a note or have your child write a note to a teacher or staff member to let them know how grateful you are for their hard work. Thank you JLS staff for all your do for our children! Many Faces, International Potluck/ Open House! Wed May 3, 5:30 8PM Please join us for our "Many Faces of JLS" and Open House event. Come to the Cafetorium starting at 5:30 PM for our biggest potluck of the year. -

Social Integration and High Achieving Columbus City Students: a Comprehensive Analysis

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Denison Student Scholarship 2021 Social Integration and High Achieving Columbus City Students: A Comprehensive Analysis Maxwell Newton Denison University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/studentscholarship Recommended Citation Newton, Maxwell, "Social Integration and High Achieving Columbus City Students: A Comprehensive Analysis" (2021). Denison Student Scholarship. 54. https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/studentscholarship/54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. Social Integration and High Achieving Columbus City Students: A Comprehensive Analysis Maxwell Douglas Newton Advisor: Dr. Fareeda Griffith Department of Anthropology/Sociology Senior Thesis 2021 Abstract: Denison Columbus Alliance scholars are a group of high achieving urban students who not only face informational gaps regarding different aspects of university life, but also class and race-based obstacles when trying to integrate into Denison University. Once scholars arrive at Denison, they perceive a major disconnect with the white and upper middle-class majority on campus due to their predominantly middle and lower-middle class upbringing as well as their experience as either people of color or their immersion in culturally diverse settings. Along with these perceptions, students face structurally created race and class-based barriers when exploring the social environment of the university. These barriers in turn effect scholar’s overall social and educational experience on campus and lead to feelings of alienation and discomfort. To overcome these obstacles, scholars develop meaningful formal and informal relationships with mentors as well engage in social coping mechanisms such as codeswitching and protective segregation within organizations that reflect their unique social locations. -

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2017 This List Is Compiled Based on Over 2 Million Song Requests Made Using the DJ Event Planner Song Request System

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs In 2017 This list is compiled based on over 2 million song requests made using the DJ Event Planner song request system. Rank Song Song Title 1 Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Killers Mr. Brightside 3 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 4 Pharrell Williams Happy 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 7 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 8 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 9 ABBA Dancing Queen 10 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 11 Bruno Mars Marry You 12 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 13 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 14 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 15 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 16 Rihanna feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 17 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 18 Ed Sheeran Shape Of You 19 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 20 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 21 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 22 Beyonce feat. Jay-Z Crazy In Love 23 Oasis Wonderwall 24 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go 25 B-52's Love Shack 26 John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 27 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 28 Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger 29 Los Del Rio Macarena 30 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 31 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 32 Toploader Dancing In The Moonlight 33 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 34 Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse Valerie 35 House Of Pain Jump Around 36 Stevie Wonder Superstition 37 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Sunday Times Magazine 11.11.2012 the Sunday Times Magazine 11.11.2012 17 VIVA FOREVER!

VIVA FOREVER! WESTSPICE UP YOUR LIFE END Brainchild of the Mamma Mia! producer Judy Craymer and written by Jennifer Saunders, the Spice Girls musical Viva Forever! launches next month. Giles Hattersley goes backstage to discover if it’s what the band want, what they really really want VIVA FOREVER! n a rehearsal room in south London, two me just before the film of Mamma Mia! came young actors are working on a scene with out [in 2008]. I sent Simon an email, saying WHERE ARE THEY NOW? all the earnest dedication required of I had to concentrate on the movie. Obviously, Baby, 36 Emma Bunton had a Ibsen. This is not Ibsen, however. At the you don’t write letters like that to Simon,” she successful solo career before back of the room, massive signs are laughs, “because I didn’t hear from him again. moving into radio presenting propped against the wall, spelling out the But I did hear from Geri in 2009. She wrote a (she has a show on Heart). immortal girl-band mantra: “Who do you sweet email, so I met her and Emma [Bunton].” She’s also been a recurring character on think you are?” It’s an existential puzzler In fact, the girls had wanted to do a musical Absolutely Fabulous and has two sons Ithat performers are encouraged to struggle for years. “It was an idea that was talked about with Jade Jones of the boyband Damage with as they wrestle with other deep emotional all the time,” says Halliwell, but Craymer fare, such as, “I’ll tell you what I want, what I hadn’t been looking to do another jukebox Ginger, 40 After quitting the Y really, really want.” Today, the show’s two leads musical (a term she hates). -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2014

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 2014 1 Killers Mr. Brightside 2 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Pharrell Williams Happy 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 Robin Thicke Blurred Lines 7 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody 8 Daft Punk Get Lucky 9 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 10 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 11 Maroon 5 MovesLike Jagger 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Bruno Mars Marry You 14 Psy Gangam Style 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 17 Rihanna We Found Love 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 19 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 20 LMFAO Sexy And I Know It 21 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 22 B-52's Love Shack 23 Beyonce Crazy In Love 24 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 25 LMFAO Party Rock Anthem 26 Amy Winehouse Valerie 27 Avicii Wake Me Up! 28 Katy Perry Firework 29 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 30 John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 31 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 32 Kenny Loggins Footloose 33 Olly Murs Dance With Me Tonight 34 OutKast Hey Ya! 35 Beatles Twist And Shout 36 One Direction What Makes You Beautiful 37 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 38 Clean Bandit Rather Be 39 Proclaimers I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles) 40 Stevie Wonder Superstition 41 Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life 42 Swedish House Mafia Don't You Worry Child 43 House Of Pain Jump Around 44 Oasis Wonderwall 45 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-go 46 Cyndi Lauper Girls Just Want To Have Fun 47 David Guetta Titanium 48 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

D2 JL S,'C,I O, R Id.IE \R ______**____ » * 1 __-MMM^M____I *""" 1 -M*********

D2 JL S,'C,I o, R iD.IE \R ______ **____ » * 1 __-MMM^M____I *""" 1 -m********* Li_A_d iJLj,__±._ w.^iJl 2LC,£.R,JL -l^-iai.lL— e, , JL 5 t & j, JiJ^ -stLL ILW [T, jn ^JilR^iE, .MSi^K.iiJi ^1.0,5 ^IHJE, .^igj>y«jf» J. 1ABOO RIBAL WARE piercings by Mike Bear Walsli fully guaranteed, trained Ly Fakir Musatar 4 30 West Pende 6 6 9 0 4 0 6 fa crrPBr Another 13 weeks of friendly competition, jokes-for-beer and amazing prizes starts up in September. So dust off the instruments and start annoying the neighbours, 'coz CiTR is now accepting demos for Shincfig 93. You should be able to play a 25-35 minute set of original material... any style, any genre. Send your tape to: SHINDIG '93, c/o CiTR Radio, #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, B.C., V6T1Z1 Don't forget to include your contact names and numbers! For more information, contact Justin or Linda at 822-3017. CiTR <££> 101.9 fM 77T; TION, promo stuff (t-shirts, WHAT YEAR IS IT, fans of "feminine boy stuff" CITR Radio, stickers, flyers...). Ex ANYWAY? here as I thought. Am I the I kindly request your change articles, sounds only person in the lower station' s help in completing good foryou? Please, have Discorder, mainland in touch with the a personal project of mine. my name put in your mail I have been trying to find Morrissey fanzine network I am attempting to col ing list. The address of the manager/ (at least 20 zines and more lect bumper and-or window In the near future, we promoter of The Grateful starting all the time)? Oh stickers from university ra will also probably discuss __£___. -

2020-2021 Freeport Area High School Musical Student Informational Packet (Grades 9-12)

Page 1 2020-2021 FREEPORT AREA HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL STUDENT INFORMATIONAL PACKET (GRADES 9-12) Dear Interested FAHS Musical Students and Families, We are excited to offer this wonderful, theatrical opportunity for you! This is a very rewarding experience every year, and it is our goal to make this a memorable, learning experience for all involved. 13 will take place on March 11th, 12th, 13th and 18th, 19th, & 20th. Please see the attached documents as you prepare for the audition process. Keep in mind that due dates, rehearsal schedules, and general procedures will be strictly followed. Please also keep in mind that we all must remain flexible and able to pivot at a moment’s notice this year due to the ever-changing situations beyond our control. All parents are responsible for providing necessary transportation (at the appropriate times) as well as any financial obligations throughout the entire process. Auditions will be done remotely using Flipgrid. The audition window will be December 14th through December 16th. Students MUST have their auditions posted on Flipgrid by 7:00 PM on December 16th. Important Items to Keep in Mind: Please read all parts of this informational packet to ensure you (or your child) are committed to this production throughout the entire process. Follow the audition process as described on page 3. Each student may audition with up to two different characters and songs. Please ensure that each audition is a separate Flipgrid video. You may or may not be cast in the roles you audition with. It is possible that students are cast in a role for which they did not audition! I’m looking forward to this great production. -

Most Requested Songs List Results

Most Requested Songs Back These lists are dynamically compiled based on online requests made over the past year at thousands of events around the world, where #1 is the most requested song. Select a List: Top 200 List Results Artist Song Add to List 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Lo... 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Se... 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre Artist Song Add to List 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

2021 Breeze Show Choir Catalog

Previously Arranged Titles (updated 2/24/21) Specific details about each arrangement (including audio samples and cost) are available at https://breezetunes.com . The use of any of these arrangements requires a valid custom arrangement license purchased from https://tresonamusic.com . Their licensing fees typically range from $180 to $280 per song and must be paid before you can receive your music. Copyright approval frequently takes 4-6 weeks, sometimes longer, so plan accordingly. If changes to the arrangement are desired, there is an additional fee of $100. Examples of this include re-voicing (such as from SATB to another voice part), rewriting band parts, making cuts, adding an additional verse, etc. **Arrangements may be transposed into a different key free of charge, provided that the change does not make re-voicing necessary** For songs that do not have vocal rehearsal tracks, these can be created for $150/song. To place an order, send an e-mail to [email protected] or submit a license request on Tresona listing Garrett Breeze as the arranger, Tips for success using Previously Arranged Titles: • Most arrangements can be made to work in any voicing, so don’t be afraid to look at titles written for other combinations of voices than what you have. Most SATB songs, for example, can be easily reworked for SAT. • Remember that show function is one of the most important things to consider when purchasing an arrangement. For example, if something is labelled in the catalog as a Song 2/4, it is probably not going to work as a closer. -

Jukebox Jade's Song List

JUKEBOX JADE’S SONG LIST BY DECADE 2010s If I Die Young – The Band Perry A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Jar Of Hearts – Christina Perri Afire Love – Ed Sheeran Last Friday Night – Katy Perry All For Love – Bryan Adams Lazy Song – Bruno Mars All I Ask – Adele Let It Go – Frozen All of Me – John Legend Locked Out Of Heaven – Bruno Mars Born This Way – Lady Gaga Love On Top – Beyonce Chandelier – Sia Marry You – Bruno Mars Diamonds – Rihanna Mean – Taylor Swift Die Young – Kesha Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 Do You Want To Build A Snowman? – Frozen Only Girl in the World – Rhianna Don’t You Worry Child – Swedish House Mafia Perfect – Ed Sheeran Elastic Heart – Sia Price Tag – Jessie J Empire State of Mind – Alicia Keys Rolling in the Deep – Adele Everglow – Coldplay Safe & Sound – Taylor Swift Firework – Katy Perry Set Fire to the Rain – Adele Forget You – Cee Lo Green Settle Down – Kimbra Girl On Fire – Alicia Keys Skinny Love – Birdy Grenade – Bruno Mars Skyfall – Adele Happy – Pharrell Williams Somebody That I Used to Know – Gotye He Won’t Go – Adele Someone Like You – Adele Hello – Adele Superficial Love – Ruth B Ho Hey! – The Lumineers The Parting Glass – Ed Sheeran Home and Away Theme – Home and Away The One That Got Away – Katy Perry How Far I’ll Go – Moana Thinking Out Loud – Ed Sheeran I’m Not the Only One – Sam Smith Titanium – Sia BY DECADE: PAGE 2 OF 22 2010s (CONTINUED) Breathless – Corinne Bailey Rae Too Good at Goodbyes – Sam Smith Bring Me to Life – Evanescence Try – Pink Bubbly – Colbie Caillat Uptown Funk – Mark Ronson -

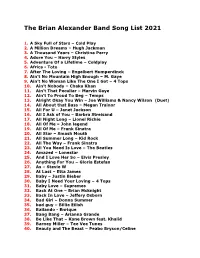

The Brian Alexander Band Song List 2021

The Brian Alexander Band Song List 2021 1. A Sky Full of Stars – Cold Play 2. A Million Dreams – Hugh Jackman 3. A Thousand Years – Christina Perry 4. Adore You – Harry Styles 5. Adventure Of a Lifetime – Coldplay 6. Africa - Toto 7. After The Loving – Engelbert Humperdinck 8. Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – M. Gaye 9. Ain’t No Woman Like The One I Got – 4 Tops 10. Ain’t Nobody – Chaka Khan 11. Ain’t That Peculiar – Marvin Gaye 12. Ain’t To Proud To Beg – Temps 13. Alright Okay You Win – Joe Williams & Nancy Wilson (Duet) 14. All About that Bass – Megan Trainor 15. All For U – Janet Jackson 16. All I Ask of You – Barbra Streisand 17. All Night Long – Lionel Richie 18. All Of Me – John legend 19. All Of Me – Frank Sinatra 20. All Star – Smash Mouth 21. All Summer Long – Kid Rock 22. All The Way – Frank Sinatra 23. All You Need Is Love – The Beatles 24. Amazed – Lonestar 25. And I Love Her So – Elvis Presley 26. Anything For You – Gloria Estefan 27. As – Stevie W 28. At Last – Etta James 29. Baby – Justin Bieber 30. Baby I Need Your Loving – 4 Tops 31. Baby Love – Supremes 32. Back At One – Brian Mcknight 33. Back In Love – Jeffery Osborn 34. Bad Girl – Donna Summer 35. bad guy – Billie Eilish 36. Bailando - Enrique 37. Bang Bang – Arianna Grande 38. Be Like That – Kane Brown feat. Khalid 39. Barney Miller – Tee Vee Tunes 40. Beauty and The Beast – Peabo Bryson/Celine 41. Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion 42.