Swiss Solidar Needs Assessment Report Nabatieh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Saturday, November 28, 2020 Report #255 Time Published: 10:30 PM

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Saturday, November 28, 2020 Report #255 Time Published: 10:30 PM The percentage of positive cases out of the number of daily tests (15 Nov– 28 Nov2020) All reports and related decisions can be found at: http://drm.pvm.gov.lb Or social media @DRM_Lebanon Distribution of Cases by Villages Beirut 108 Baabda 180 Maten 152 Chouf 85 Kesserwan 105 Akkar 68 Ein Al Mreisseh 3 Chiah 21 Borj Hammoud 13 Damour 1 Sarba 6 Halba 6 Ras Beirut 1 Jnah 2 Sin El Fil 7 Naameh 2 Kaslik 2 Sweiset Akkar 1 Manara 2 Ouzai 4 Jdeidet El Metn 4 Chhim 9 Zouk Michael 8 Ilat 1 Rouche 7 Bir Hassan 1 Ras Al Jdideh 1 Daraya 3 Ghadir 6 Tikrit 1 Hamra 7 Mhattet El Sfeir 1 Bouchrieh 2 Ketermaya 6 Zouk Mosbeh 5 Oyoun 1 Ein Tineh 2 Ghobeiry 6 Dora 5 Anout 3 Adonis 2 Koucha 1 Mseitbeh 7 Ein Al Rimmaneh 15 Rouda 4 Sibline 1 Haret Sakhr 2 Hayssa 1 Mar Elias 1 Firn El Shebbak 4 Sed Al Bouchrieh 1 Borjein 1 Tabarja 1 Abboudieh 1 UNESCO 1 Haret Hreik 19 Sabtieh 5 Barja 4 Safra 7 Bebnine 7 Tallet El Khayat 6 Lailaky 9 Dekweneh 9 Baasir 1 Bouar 2 Nahr El Bared 1 Zarif 2 Borj Al Brajneh 35 Mkalles 3 Dibbieh 1 Aqaibeh 1 saysouq 1 Mazraa 7 Mreijeh 6 Antelias 5 Jiyyeh 5 Ajaltoun 7 Berqayel 6 Borj Abi Haidar 6 Tahweetet Al Ghadir 1 Manqalet Mezher 1 Jadra 1 Ballouneh 1 Denbo 1 Tarik Jdideh 5 Baabda 2 Jal El Dib 1 Wady Al Zainy 6 Sehaileh 2 Qab'eit 8 Ras El Nabaa 3 Hazmieh 7 Zalqa 4 Wardanieh 4 Ein Al Rihaneh 1 Meshmesh 2 Rasta El Tahta 1 Mar Taqla 1 Byaqout 2 Mgheirieh 1 Jeita 3 Fneidek 3 Rmeil 2 Hadat 27 Dbayeh 15 Zaarourieh 2 Ghazir -

Interim Report on Humanitarian Response

INTERIM REPORT Humanitarian Response in Lebanon 12 July to 30 August 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. THE LEBANON CRISIS AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE ............................................... 1 2.1 NATURE OF THE CRISIS...................................................................................................... 1 2.2 THE INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE DURING THE WAR............................................................. 1 2.3 THE RESPONSE AFTER THE CESSATION OF HOSTILITIES ..................................................... 3 2.4 ORGANISATION OF THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE ............................................................. 3 2.5 EARLY RECOVERY ............................................................................................................. 5 2.6 OBSTACLES TO RECOVERY ................................................................................................ 5 3. HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE IN NUMBERS (12 JULY – 30 AUGUST) ................................... 6 3.1 FOOD ................................................................................................................................6 3.2 SHELTER AND NON FOOD ITEMS......................................................................................... 6 3.3 HEALTH............................................................................................................................. 7 3.4 WATER AND -

Inter-Agency Q&A on Humanitarian Assistance and Services in Lebanon (Inqal)

INQAL- INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) Disclaimers: The INQAL is to be utilized mainly as a mass information guide to address questions from persons of concern to humanitarian agencies in Lebanon The INQAL is to be used by all humanitarian workers in Lebanon The INQAL is also to be used for all available humanitarian hotlines in Lebanon The INQAL is a public document currently available in the Inter-Agency Information Sharing web portal page for Lebanon: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/documents.php?page=1&view=grid&Country%5B%5D=122&Searc h=%23INQAL%23 The INQAL should not be handed out to refugees If you and your organisation wish to publish the INQAL on any website, please notify the UNHCR Information Management and Mass Communication Units in Lebanon: [email protected] and [email protected] Updated in April 2015 INQAL- INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) EDUCATION ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 FOOD ........................................................................................................................................................................ 35 FOOD AND ELIGIBILITY ............................................................................................................................................ -

9685436* Oficiales Del Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/PV.3653 Consejo de Seguridad Provisional Quincuagésimo primer año ª 3653 sesión Lunes 15 de abril de 1996, a las 18.00 horas Nueva York Presidente: Sr. Somavía ...................................... (Chile) Miembros: Alemania ........................................ Sr.Eitel Botswana ....................................... Sr.Nkgowe China .......................................... Sr.QinHuasun Egipto .......................................... Sr.Elaraby Estados Unidos de América ........................... Sra. Albright Federación de Rusia ................................ Sr.Lavrov Francia ......................................... Sr.Dejammet Guinea-Bissau .................................... Sr.Queta Honduras ....................................... Sr.Martínez Blanco Indonesia ........................................ Sr.Wibisono Italia ........................................... Sr.Terzi di Sant’Agata Polonia ......................................... Sr.Włosowicz Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda del Norte ........... Sr.Plumbly República de Corea ................................ Sr.Park Orden del día La situación en el Oriente Medio Carta de fecha 13 de abril de 1996 dirigida al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente del Líbano ante las Naciones Unidas (S/1996/280) 96-85436 (S) La presente acta contiene la versión literal de los discursos pronunciados en español y de la interpretación de los demás discursos. El texto definitivo será reproducido en los Documentos *9685436* Oficiales -

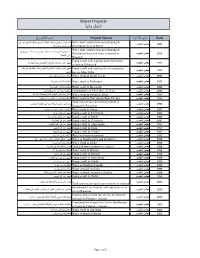

Water Projects ﻣﺎﺋﯾﺔ أﺷﻐﺎل

Water Projects أشغال مائية Date إٍسم اﻹدارة Project Name إسم المشروع & Water tank construction and pumping بناء خزان ارضي وتمديد شبكات توزيع وخطوط دفع وجر في 1997 مجلس الجنوب distribution lines in Dweir قرى الدوير وجوارها Water tank construction and pumping & بناء خزان علوي وتمديد خطوط دفع وجر وشبكات توزيع في 1995 مجلس الجنوب distribution lines and water networks in وادي النبطية Nabatieh Equip a well with a pump and chlorination 1997 مجلس الجنوب تجهيز البئر بمعدات الضخ والتعقيم في بلدة الهبارية system in Hebariyeh Equip a well and construction of a pumping تجهيز البئر بمعدات الضخ والتعقيم وانشاء خط دفع في بلدة 1997 مجلس الجنوب line in Jabin Town الجبين 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Majdl Selem اشغال مائية في مجدل سلم 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Mahrouna اشغال مائية في محرونة 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Baysarieh اشغال مائية في البيسارية 1995 مجلس الجنوب Continuation of Fakherdine Velley's استكمال مياه آبار وادي فخرالين 1995 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Nabatieh Tahta اشغال مائية في النبطية التحتا )محدلة الدباغة( 1996 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Deir Anoun Rass EL Ain اشغال مائية في دير قانون رأس العين Tank construction and water network in 1996 مجلس الجنوب بناء قصر مائي وشبكة مائية في قعقعية الصنوبر Qaaqayieh Sanawbar 1997 مجلس الجنوب Water work in Dweir اشغال مائية في الدوير وجوارها 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Teir Harfa تجهيز بئر طير حرفا 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Debel تجهيز بئر وخط دفع في دبل 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Hebariyeh تجهيز بئر في الهبارية 1997 مجلس الجنوب Equip a well in Alma shaab تجهيز بئر في علما -

Syria Refugee Response ±

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON South and El Nabatieh Governorates Saida 568 172 Chouf West Bekaa 152 13 Kassab ! 151 Hospital ! v® Mount Chouf 148 Lebanon ! 712 116 ! 149 ! 1,179 118 ! ! P ! 11,917 ! 147 115 ! 8 ! 117 ! ! Hammoud Hospital P 8 v® 13 ! 10 146 ! University 123 30 Medical Center 172 568 152 151 ! ! West v® Kassab Hospital 111648 150 155 !149 80 33 54 2 ! 118 !! 153 75 18 Bekaa ! !115 117 Hammoud Hospital 80 69 $ !!! ! Health Medic1a4l6 ! v® University 110 32 114 147! ! 116 South 1$142 ! ! Center (prev. ! Medical Center 60 150 155 352 18 Assayran Hospital) v® 253 Saida 4 100 1,010 40 99 7 Hospital (Gov.) !! ! 17 Health Medical ! 140 9 94 v® 141 182 Center (prev. 3 1,010 142 ! 143 ! 103 Jezzine ! ! 104 Assayran Hospital) 324 129 5 145 ! 106 Hospital ! 133 ! 2,190 102 v® Raee 13 ! (Gov.) v® 70 ! ! Hospital Bekaa P 174 40 89 v® 379 ! Jezzine 770 ! ! 81 ! 138 ! ! 4 109 ! 4 135 ! 716 99 31 12 2 108 ! 121 6 ! ! 144 111 4 134 ! ! Rachaya ! Saida 140 113 125 ! 557 ! ! 20 4,250 90 Hospital 132 ! ! 126 (Gov.) P! ! ! ! 156 ! ® v 553 72 661 P Jezzine 2,190 ! P 137 105 P ! Jezzine ! ! 448 ! 128 ! ! P 140 5 142 P 18 30 54 ! 4 ! ! 114 ! 99 ! 136 101 ! ! ! 304 ! P ! ! !P ! 145 143 ! !P! P P 187 110 ! !! ! 6 ! 16 53 ! ! ! ! ! P P ! P ! P 17 97 !! 516 ! ! ! Sour P P ! ! P! ! 5 5 ! ! 37 ! P ! ! ! 198 ! P ! ! 87 !! !! 87 4 P ! 13!1 !! 60 ! ! P! Saida 16 99 49 ! ! ! ! 1,708 -

Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon During the 2006 War

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 5(E) Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon .............................................................................1 Map: Southern Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 2 Map: Northern Lebanon ........................................................................................................ 3 I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll ....................................................... 6 Hezbollah Conduct During the War .................................................................................. 14 Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected ............................................................... 17 II. Recommendations........................................................................................................ 20 III. Methodology................................................................................................................ 23 IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict......................................................................31 A. Applicable International Law ....................................................................................... 31 B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects ...............................................................33 -

Lebanon Fire Risk Bulletin

Lebanon Fire Risk Bulletin Refer to cadast table condition. CIVIL DEDEFENCE Please note that the indicated temperature is at 2 meters height from the ground. General description of potential fire risk situation Symbol Level of Meaning and actions risk Very Very low fire risk. Controlled burning operations can be hardly executed due to high fuel moisture content. Normally VL low wildfires self-extinguish. Low Low fire risk. Controlled burning operations can be executed with a reasonable degree of safety. L Medium Medium-low fire risk. Controlled burning operations can be executed in safety conditions. All the fires need to be ML low extinguished. Medium Medium fire risk. Controlled burning operations would be avoided. All the fires need to be very well extinguished. M Medium Controlled burning is not recommended. Open flame will start fires. Cured grasslands and forest litter will burn readily. Spread is moderate in forests and fast in exposed areas. Patrolling and monitoring is suggested. Fight fires M high with direct attack and all available resources. Ignition can occur easily with fast spread in grass, shrubs and forests. Fires will be very hot with crowning and short High to medium spotting. Direct attack on the head may not be possible requiring indirect methods on flanks. Patrolling H and monitoring the territory is highly suggested. Ignition can occur also from sparks. Fires will be extremely hot with fast rate of spread. Control may not be possible Extreme during day due to long range spotting and crowning. Suppression forces should limit efforts to limiting lateral spread. E Damage potential total. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR6647 Implementation Status & Results Lebanon LB - Municipal Infrastructure (P103875) Operation Name: LB - Municipal Infrastructure (P103875) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 12 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 11-Jan-2012 Country: Lebanon Approval FY: 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:Special Financing Region: MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 03-Nov-2006 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2009 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 11-Jan-2012 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 29-Nov-2006 Revised Closing Date 30-Apr-2012 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The objectives of the additional financing grant are to (i) restore basic services and rebuild priority public infrastructure in the affected municipalities and villages, (ii) support local economic recovery and development in the municipalities that have suffered the heaviest damage, and (iii) provide technical assistance to and build the capacity of municipalities to mitigate the impact of the hostilities on municipal finances (within the broader context of developing the municipal sector). Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Public Disclosure Authorized Yes No Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Reconstruction of Public Infrastructure 18.00 Municipal Recovery and Development 9.00 Project Management and Capacity Building 3.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview The Project is now complete. -

Expanded Programme of Immunization Study

Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 Expanded Programme on Immunization District-Based Immunization Coverage Cluster Survey 1 Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 Acknowledgment Special acknowledgment goes to the Director General of the Ministry of Public Health, Dr. Walid Ammar for his guidance, and Dr Randa Hamadeh, head of the Primary Health Care department for facilitating the process of the study. Particular thanks goes to Dr. Gabriele Riedner, WHO Representative in Lebanon Country Office, for her unconditional support and Dr. Alissar Rady for her technical guidance all through the design and implementation process, and the country office team as well as the team at WHO Regional Office. The Expanded Programme on Immunization, district-based immunization coverage cluster survey, would not have been possible without the generous financial support of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the World Health Organization. This EPI cluster survey was conducted by the Connecting Research to Development center, contracted by and under the guidance of WHO and with the overall supervision of the MOPH team. 2 Expanded Programme on Immunization 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures......................................................................................................................................... -

D D D L'8:L D

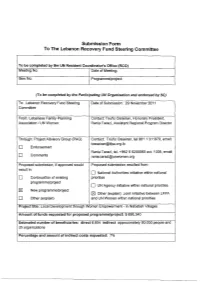

Submission Form To The Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Committee To be completed by the UN Resident Coordinator's Office (RCO) Meeting No: Date of Meeting: Item No: Programme/project: (To be completed by the Participating UN Organisation and endorsed by SC) To: Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Date of Submission: 29 November 2011 Committee From: Lebanese Family Planning Contact: Toufic Osseiran, Honorary President, Association I UN Women Rania Tarazi, Assistant Regional Program Director Through: Project Advisory Group (PAG) Contact: Toufic Osseiran, tel 961 1 311978, email: [email protected] D Endorsement Rania Tarazi, tel. +962 6 5200060 ext. 1008, email: D Comments [email protected] Proposed submission, if approved would Proposed submission resulted from: result in: D National Authorities initiative within national D Continuation of existing priorities programme/project D UN Agency initiative within national priorities l'8:l New programme/project l'8:] Other (explain): Joint initiative between LFPA D Other (explain) and UN Women within national priorities Project title: Local Development through Women Empowerment- in Nabatieh Villages Amount of funds requested for proposed programme/project: $ 698,340 Estimated number of beneficiaries: direct 6,604 indirect approximately 90,000 people and 35 organizations Percentage and amount of indirect costs requested: 7% Background The project was jointly developed by UN Women and the Lebanese Family Planning Association (LFPA). UN Women, an non-resident agency in Lebanon, conducted a gender needs assessment in April 2011 to identify entry points for its technical support to national organizations within its mandate of gender equality. In addition to identifying potential partners, the gender needs assessment has shown that women have not been systematically included in the recovery and reconstruction efforts in Lebanon. -

Inter-Agency Q&A on Humanitarian Assistance and Services in Lebanon

INQAL- EDUCATION - INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) Disclaimers: The INQAL is to be utilized mainly as a mass information guide to address questions from persons of concern to humanitarian agencies in Lebanon The INQAL is to be used by all humanitarian workers in Lebanon The INQAL is also to be used for all available humanitarian hotlines in Lebanon The INQAL is a public document currently available in the Inter-Agency Information Sharing web portal page for Lebanon: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=122 The INQAL should not be handed out to refugees If you and your organisation wish to publish the INQAL in any website, please notify the UNHCR Information Management and Mass Information Units in Lebanon: [email protected] and [email protected] Updated in October 2014 INQAL- EDUCATION - INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) EDUCATION ................................................................................................................................................... 3 FOOD ........................................................................................................................................................... 27 FOOD AND ELIGIBILITY ................................................................................................................................. 66 HOUSEHOLD