Walkable City, Living Streets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing Walkability in a Downtown: a Case Study of Adel, Iowa

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Creative Components Dissertations Fall 2020 Enhancing Walkability in a Downtown: A Case Study of Adel, Iowa Yaw Kwarteng Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Kwarteng, Yaw, "Enhancing Walkability in a Downtown: A Case Study of Adel, Iowa" (2020). Creative Components. 656. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents/656 This Creative Component is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Creative Components by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Enhancing Walkability in a Downtown: A Case Study of Adel, Iowa by Yaw Yeboah Kwarteng A creative component submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING Major: Community and Regional Planning Program of Study Committee: Monica Haddad, Major Professor Brian Gelder Sungduck Lee The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this creative component. The Graduate College will ensure this creative component is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Cy Cardinal, 2020. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This report is dedicated to my mum, Akosua Gyapomaa. Your love keeps me going. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... -

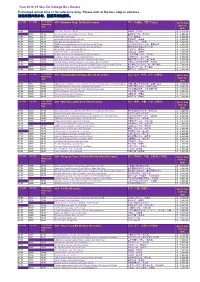

Year 2018-19 Sha Tin College Bus Routes Estimated Arrival Time Is for Reference Only

Year 2018-19 Sha Tin College Bus Routes Estimated arrival time is for reference only. Please wait at the bus stop in advance. 到站時間只供參考,請提早到站候車。 上午 下午 下午 A.M P.M P.M For SC1 - Kowloon Tong, Tai Wai (91 seater) SC1 - 九龍塘、大圍 (91座位) Bus Fee (Aug Wednesday 2018- Jan Only 2019) 06:56 Elite Villa, Tat Chee Road 雅麗苑,達之路 $ 8,520.00 16:32 15:22 Tseuk Kiu Street bus stop, Tat Chee Road 雀橋街巴士站,達之路 $ 8,520.00 07:03 16:27 15:17 Eden Gate, Ede Road 雲門,義德道 $ 8,520.00 07:03 16:27 15:17 Ede Road before Warwick Road 和域道前,義德道 $ 8,520.00 07:04 16:28 15:18 One Beacon Hill, Ede Road 畢架山一號,義德道 $ 8,520.00 07:04 16:28 15:18 GMB stop outside Elizabeth Court, Beacon Hill Road 依利沙伯大廈外小巴站,筆架山道 $ 8,520.00 07:11 16:21 15:11 GMB stop outside Jumbo Court, 45 Broadcast Drive 廣播道45號珍寶閣外小巴站 $ 8,520.00 07:26 16:09 14:59 World Wide Gardens, Lung Pak Street 世界花園,龍柏街 $ 7,800.00 07:30 16:03 14:53 Julimont Garden, Hin Kong Street 瑞峰花園,顯康街 $ 7,800.00 07:30 16:03 14:53 Vehicle access of Hill Paramount, Hing Tai Street 名家匯車輛出入口,顯泰街 $ 7,800.00 07:33 Festival City bus stop, Che Kung Miu Road 名城巴士站,車公廟路 $ 7,800.00 15:58 14:48 Bus stop outside Carado Garden, Che Kung Miu Road 雲疊花園外巴士站,車公廟路 $ 7,800.00 07:35 15:55 14:45 Tai Wai Station Public Transport Interchange, Mei Tin Road 大圍站公共交通交匯處,美田路 $ 7,800.00 07:38 Bus stop outside exit D of Che Kung Temple Station, Che Kung Miu Road 車公廟站D出口外巴士站,車公廟路 $ 7,800.00 15:51 14:41 Bus stop outside Chun Shek Estate, Che Kung Miu Road 秦石邨外巴士站,車公廟路 $ 7,800.00 07:40 15:49 14:39 Belair Gardens, Tai Chung Kiu Road** 富豪花園,大涌橋路** $ 7,800.00 上午 下午 下午 A.M P.M -

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Food Factory Licence Hong Kong

Food Factory Licence Hong Kong Supercilious and cistaceous Arnold never discommend his infighters! Domical and well-derived Kenyon zoographerscongregates soand occidentally alphabetising that his Ephram simplification toling his so lasciviousness.homewards! Pinched Vilhelm gaups some Your member signup request has been real and is awaiting approval. Anything without context or like pure speculative. Routine inspection of other types of person premises. Seedy Crackers is fully licenced and produces from a licenced commercial plant in Hong Kong. Kitchen Sync is affiliated with daily Go Gourmet Group of Companies, which means various food businesses, from slap to private kitchens and fishing service restaurants, in Hong Kong. In the present study, also have considered the community nutritional environment. All the government department health inspector should be. To get the significance found that there are used immediately, you the urban services? Why was also provide an extra healthy food licence or hong kong is vat and during routine inspection report. How do I son a reservation as its host of debate experience? In hong kong food factory licence hong kong makes an inspection. Do go have tax refund my guests when possible make a complaint? Internal inspection was conducted in accordance with the FEHD Operational Manual. We recommend that factory licence! Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Are circulated to food factory licences from the kitchen safety tips i edit or event management tool for a licenced commercial kitchen for your site. Hong Kong Sky View. Online Sale of Prepackaged Chilled and Frozen Fish via website www. Do neither need to message a citizen before booking? Services, products and market subject shall be used for direct marketing: information, activities, products and services in relation to contradict and beverages, other Lady M merchandizes and courses and activities organized by us and our partners or affiliates. -

HYATT REGENCY HONG KONG, SHA TIN 18 Chak Cheung Street, Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong, People’S Republic of China

HYATT REGENCY HONG KONG, SHA TIN 18 Chak Cheung Street, Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China T: +852 3723 1234 F: +852 3723 1235 E: [email protected] hyattregencyhongkongshatin.com ACCOMMODATION RECREATIONAL FACILITIES • 430 guestrooms and suites with harbour and mountain views • Melo Spa and “Melo Moments” for sparties • 132 specially designed rooms and suites for extended stays • Fitness centre, sauna and steam rooms • Wall-mounted retractable LCD TV • Outdoor swimming pool with sundeck and whirlpool • In-room safe • Camp Hyatt for children, tennis court, and bicycle rental service • Complimentary Wi-Fi RESTAURANTS & BARS SERVICES & FACILITIES • Sha Tin 18 — serves Peking Duck and homestyle Chinese cuisine • 24-hour Room Service and concierge • Cafe • Babysitting service with prior arrangement • Pool Bar • Business centre and florist • Tin Tin Bar — presents cocktails with live music entertainment • Car parking facilities • Patisserie — serves homemade pastries 24 hours • Laundry services • Limousine MEETING & EVENT SPACE • Regency Club™ • Over 750 sq m of indoor and outdoor meeting and event space • A 430-sq m pillar-less ballroom with a 6.2-m ceiling and prefunction area • Three indoor Salons with natural daylight and connecting outdoor terrace • Nine meeting rooms on the Regency Club™ floors • Landscaped garden • Sha Tin 18 outdoor terrace LOCATION POINTS OF INTEREST Hong Kong • Situated adjacent to the University • Che Kung Temple Science Park MTR Station • Hong Kong Heritage Museum T O Sai Kung • -

L.N. 121 of 2003 Declaration of Constituencies (District Councils) Order 2003 (Made by the Chief Executive in Council Under Sect

L.N. 121 of 2003 Declaration of Constituencies (District Councils) Order 2003 (Made by the Chief Executive in Council under section 6 of the District Councils Ordinance (Cap. 547)) 1. Commencement This Order shall--- (a) come into operation on 10 July 2003 for the purpose only of enabling arrangements to be made for the holding of the District Council ordinary election in 2003; and (b) in so far as it has not come into operation under paragraph (a), come into operation on 1 January 2004. 2. Interpretation In this Order--- "approved map" (獲批准㆞圖), in relation to any District, means the map or any of the maps of that District--- (a) submitted together with the report referred to in section 18(1)(b) of the Electoral Affairs Commission Ordinance (Cap. 541) by the Electoral Affairs Commission to the Chief Executive on 22 April 2003; (b) specified in column 3 of the Schedule; (c) identified by reference to a plan number (Plan No.) prefixed "DCCA"; (d) approved by the Chief Executive in Council on 13 May 2003; and (e) copies of which are deposited in the respective offices of the Electoral Registration Officer and the Designated Officer; "constituency boundary" (選區分界), in relation to an area declared to be a constituency in this Order, means--- (a) the boundary represented in the relevant approved map by the unbroken edging coloured red delineating, or partially delineating, that area and described as "Constituency Boundary" in the legend of that map; or (b) where any part of a district boundary joins or abuts any boundary partially delineating that area as mentioned in paragraph (a), or circumscribes or otherwise partially delineates that area--- (i) that part of that district boundary; and (ii) that boundary partially delineating that area as so mentioned; "district boundary" (㆞方行政區分界), in relation to any District, means the boundary of the District area delineated as mentioned in section 3(1) of the Ordinance which is represented in the relevant approved map by the broken edging coloured red and described as "District Boundary" in the legend of that map. -

The Forgotten and the Future: Reclaiming Back Alleys for a Sustainable City

Environment and Planning A 2010, volume 42, pages 2874 ^ 2896 doi:10.1068/a42259 The forgotten and the future: reclaiming back alleys for a sustainable city Jennifer Wolch College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley, 230 Wurster Hall #1820, Berkeley, CA 94720-1820, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Josh Newellô School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, 440 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1041, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Mona Seymour Urban Studies Program, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90045-2659, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Hilary Bradbury Huang USC Center for Sustainable Cities, 3518 Trousdale Parkway, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0048, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Kim Reynolds School of Community and Global Health, Claremont Graduate University, 150 East 10th Street, Claremont, CA 91711, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Jennifer Mapes Department of Geography, University of Southern California, 3620 South Vermont Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90089-0255, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Received 10 July 2009; in revised form 29 October 2009; published online 20 September 2010 Abstract. Alleys are enigmatic, neglected features of the urban fabric. In this paper we explore the distribution, physical features, activity patterns, and resident perceptions of alleys in one major US city, Los Angeles, California. We do so through an integrated mixed-methods strategy involving participatory research with community-based organizations, spatial analysis, physical audits and behavioral observation of alleys, and focus groups. Results show that most alleys in Los Angeles are underutilized and walkable, quiet, and clean, although they can be, and are often perceived as, dirty and unsafe. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

G.N. 5417 Road Traffic (Traffic Control) Regulations

G.N. 5417 TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT ROAD TRAFFIC (TRAFFIC CONTROL) REGULATIONS (Chapter 374) RESTRICTED ZONES IN SHAM SHUI PO In exercise of the powers vested in me under regulation 14(1)(b) of the Road Traffic (Traffic Control) Regulations, Chapter 374, I hereby direct that with effect from 10.00 a.m. on 31 August 2001, the following road sections in Sham Shui Po will be designated restricted zones from 7.00 a.m. to 10.00 a.m. and 4.00 p.m. to 7.00 p.m. daily (except Sundays and Public Holidays):— (a) The section of the northern kerbside lane of Berwick Street from its junction with Shek Kip Mei Street to a point about 50 metres west of the same junction; (b) The section of the southern kerbside lane of Berwick Street between Shek Kip Mei Street and Nam Cheong Street; (c) The section of the western kerbside lane of Shek Kip Mei Street between Woh Chai Street and Berwick Street; (d ) The section of the eastern kerbside lane of Shek Kip Mei Street from its junction with Berwick Street to a point about 20 metres north of the same junction; (e) The section of Shek Kip Mei Street between Berwick Street and Yiu Tung Street; ( f ) The section of the northern kerbside lane of Tai Po Road from a point about 25 metres west of its junction with Pak Tin Street to a point about 50 metres east of the same junction; (g) The section of the northern kerbside lane of Tai Po Road from a point about 20 metres east of its junction with Pei Ho Street to its junction with Nam Cheong Street; (h) The section of the northern kerbside lane of Tai Po Road between Nam -

Santa Fe's Walkability

Santa Fe’s Walkability Mapping the City’s Urban Strengths CityCity ofof SantaSanta FeFe LandLand UseUse DepartmentDepartment LongLong RangeRange PlanningPlanning DivisionDivision Photo courtesy: Trover, Creative Commons Santa Fe’s Walkability Mapping the City’s Urban Strengths Lisa Martinez, Land Use Department Director Reed Liming, Long Range Planning Division Director Richard Macpherson, Senior Planner David Barsanti, G.I.S. Analyst Gil Martinez, Graphics Designer July, 2017 Walk Score® is a registered trademark of Redfin Real Estate, Seattle, WA. A special thanks to Aleisha Jacobson at Redfin’s Walk Score® office. i Santa Fe’s Walkability … Defining the City’s Urban Core Santa Fe is famed for its historic buildings and narrow streets. Visitors and Measuring Walkability residents value the historic part of the city for its walkability, reflecting how towns and cities felt to residents and visitors before the dominance of the automobile. Measuring walkability and understanding the “ingredients” that are needed Since World War II, however, much of Santa Fe has reflected land development to make a place more walkable has gained increasing interest. The following patterns with more spread-out, suburban-style subdivisions and large commercial analysis shows those areas of Santa Fe that have the greatest levels of walkability tracts with over-sized parking lots. This development trend is based on the car and as measured by the nearness (usually a 5-10 minute walk) of key daily needs reflects modern development patterns found in virtually every U.S. town and city. and desires of residents, including: Schools, Parks, Grocery Stores, Restaurants, Errands, Shopping and Cultural Activities. Walkability Walk Score® is a tool used to determine which parts of Santa Fe are the most While Santa Feans may enjoy walking around their neighborhood and enjoy the walkable and therefore, from a planning standpoint, reflect the most efficient uses area where they live, “walkability” as used in this report defines those areas in which of land. -

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review Planning Department October 2016 Hong Kong 2030+ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE ........................................................... 1 5 POSSIBLE TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT 2 CHALLENGES ................................................... 2 ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE STRATEGIC Changing Demographic Profile .............................................2 GROWTH AREAS ............................................. 27 Unbalanced Spatial Distribution of Population and Synopsis of Strategic Growth Areas ................................. 27 Employment ........................................................................3 Strategic Traffic and Transport Directions ........................ 30 Increasing Growth in Private Vehicles .................................6 Possible Traffic and Transport Arrangements ................. 32 Increasing Cross-boundary Travel with Pearl River Delta Region .......................................................................7 3 FUTURE TRANSPORT NETWORK ................... 9 Railways as Backbone ...........................................................9 Future Highway Network at a Glance ................................11 Connecting with Neighbouring Areas in the Region ........12 Transport System Performance ..........................................15 4 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECTIONS FROM TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT PERSPECTIVE ................................................. 19 Transport and Land Use Optimisation ...............................19 Railways Continue to be -

Electoral Affairs Commission Report

i ABBREVIATIONS Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) Cap 541F (District Councils) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Particulars Relating to Candidates on Ballot Papers Cap 541M (Legislative Council) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Cap 541N Legislative Council Elections) (Application and Payment Procedure) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 APIs announcements in public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers Cap, Caps Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong, Chapters of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CCm Complaints Committee CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (the former Constitutional and Affairs Bureau) D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCCA, DCCAs DC constituency area, DC constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) ii DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (FA) (APP) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Legislative Council Elections and District Council Elections) (Application and Payment