Shadow Vigilante Officials Manipulate and Distort to Force Justice from an Apparently Reluctant System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toxic Masculinity and the Revolutionary Anti-Hero

FIGHTING HACKING AND STALKING: TOXIC MASCULINITY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-HERO A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A In partial fulfillment of 3^ the requirements for the Degree kJQ Masters of Arts *0 4S In Women and Gender Studies by Robyn Michelle Ollodort San Francisco, California May 2017 Copyright by Robyn Michelle Ollodort 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Fighting, Hacking, and Stalking: Toxic Masculinity and the Revolutionary Anti-Hero by Robyn Michelle Ollodort, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Women and Gender Studies at San Francisco State University. Martha Kenney; Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Women and Gender Studies Professor, History FIGHTING, HACKING, AND STALKING: TOXIC MASCULINITY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-HERO Robyn Michelle Ollodort San Francisco, California 2017 Through my analyses of the films Taxi Driver (1976) and Fight Club (1999), and the television series Mr. Robot (2105), I will unpack the ways each text represents masculinity and mental illness through the trope of revolutionary psychosis, the ways these representations reflect contemporaneous political and social anxieties, and how critical analyses of each text can account for the ways that this trope fails to accurately represent the lived experiences of men and those with mental illnesses. In recognizing the harmful nature of each of these representations’ depictions of both masculinity and mental illness, we can understand why such bad tropes circulate, and how to recognize and refuse them, or make them better. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

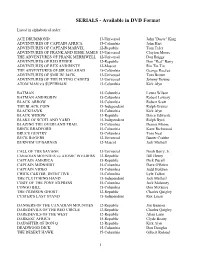

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Vigilantes, Incorporated: an Ideological Economy of the Superhero Blockbuster

VIGILANTES, INCORPORATED: AN IDEOLOGICAL ECONOMY OF THE SUPERHERO BLOCKBUSTER BY EZRA CLAVERIE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English with a minor in Cinema Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor José B. Capino, Chair Associate Professor Jim Hansen Associate Professor Lilya Kaganovsky Associate Professor Robert A. Rushing Professor Frank Grady,Department of English, University of Missouri, Saint Louis ii ABSTRACT Since 2000, the comic-book superhero blockbuster has become Hollywood’s most salient genre. “Heroes, Incorporated: A Political Economy of the Superhero Blockbuster” examines these seemingly reactionary fantasies of American power, analyzing their role in transmedia storytelling for a conglomerated and world-spanning entertainment industry. This dissertation argues that for all their apparent investment in the status quo and the hegemony of white men, superhero blockbusters actually reveal the disruptive and inhuman logic of capital, which drives both technological and cultural change. Although focused on the superhero film from 2000 to 2015, this project also considers the print and electronic media across which conglomerates extend their franchises. It thereby contributes to the materialist study of popular culture and transmedia adaptation, showing how 21st century Hollywood adapts old media for new platforms, technologies, and audiences. The first chapter traces the ideology of these films to their commercial roots, arguing that screen superheroes function as allegories of intellectual property. The hero’s “brand” identity signifies stability, even as the character’s corporate owners continually revise him (rarely her). -

Stories of Revenge in Italian Popular Culture. a Narrative Study of Vigilante Films Ferdinando Spina*

Stories of Revenge in Italian Popular Culture. A Narrative Study of Vigilante Films Ferdinando Spina* Author information * Department of History, Society and Human Studies, University of Salento, Italy. Email: ferdinando. [email protected] Article first published online July 2019 HOW TO CITE Spina, F. (2019). Stories of Revenge in Italian Popular Culture. A Narrative Study of Vigilante Films. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 11(2), 218-252. doi: 10.14658/pupj-ijse-2019-2-11 VA ADO UP P Stories of Revenge in Italian Popular Culture. A Narrative Study of Vigilante Films Ferdinando Spina* Abstract: In recent years, we have witnessed, particularly in Italy, a growing support for the “self-defence” argument and the vigilante justice. This troubling phenomenon requires further empirical and theoretical attention to determine why and how media manage to draw the interest of the public when they tackle revenge and private justice topics. The objective of this paper is to explore narratives of private revenge in popular culture, specifically in Italian cinema. The first section introduces some reflections on the relations between narrative and criminology and the interest of cinema in revenge tales. Then follows a reconstruction of the historical evolution and narrative structures of both American and Italian vigilante films. Finally, a detailed analysis is presented of a representative sample of Italian films of the genre, highlighting the narrative structures and main themes, as well as the similarities and differences with respect to the American models. Keywords: private justice, vigilantism, narrative, popular criminology, vigilante film * Department of History, Society and Human Studies, University of Salento, Italy. -

©2013 Casey Shevlin All Rights Reserved

©2013 CASEY SHEVLIN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Casey Shevlin May, 2013 A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY Casey Shevlin Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of College Dr. Patrick Chura Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Dean of Graduate School Dr. Hillary Nunn Dr. George R. Newkome ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Julie Drew ______________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………1 II. “THEY’RE THE SAME ONES THAT LYNCH NEGROES”: VIGILANTES AND LYNCH MOBS IN STEINBECK’S IN DUBIOUS BATTLE……...…………………....7 III. STEINBECK’S OF MICE AND MEN: A LYNCHING NOVEL……………….….27 IV. STEINBECK’S THE GRAPES OF WRATH: LYNCHING AND RACIAL INSTABILITY IN THE 1930s WEST…………………………………………………..47 V. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS…………………………………..................................67 LITERATURE CITED.………………………………………………………………….71 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 3.1 Life Magazine Photo………………………..........……………………..………..29 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This thesis will explore the subject of lynching in John Steinbeck’s work, specifically his 1930s labor trilogy: In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). My interest in John Steinbeck’s work and its connection to lynching was sparked by a particular reading of his 1937 novel, Of Mice and Men. I say particular because I have encountered the novel many times. -

A Historical/Critical Analysis of the Tv Series the Fugitive

A HISTORICAL/CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TV SERIES THE FUGITIVE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By David P. Pierson, B.S. Denton, Texas May, 1993 Pierson, David P., A Historical/Critical Analysis Of The TV Series The Fugitive. Master of Science (Radio/TV/Film), May 1993, 168 pp., bibliography, 70 titles. In many respects, the popular 1960's television series, The Fugitive perfectly captured the swelling disillusionment with authority, alienation, and discontent that soon encompassed American society. This historical/critical study provides a broad overview of the economic, social, and political climate that surrounded the creation of The Fugitive. The primary focus of this study is the analysis of five discursive topics (individualism, marriage, justice & authority, professionalism, science and technology) within selected episodes and to show how they relate to broader cultural debates which occurred at that time. Finally, this study argues that The Fui1gitive is a part of a television adventure subgenre which we may classify as the contemporary "wanderer-hero" narrative and traces its evolution through selected television series from the last three decades. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . 1 The Sixties The Emergence of a Television Culture The Fugitive Notes on Methodology II. THE TV INDUSTRY AND THE FUGITIVE . 26 The Great Shift ABC-TV Network and the Creation of The Fugitive 60's Programming Trends and The Fugitive III. THE DISCURSIVE FUGITIVE . 70 Individualism Marriage Justice and Authority Professionalism Science and Technology Conclusion IV. -

Revenge and the Rule of Law in Nineteenth-Century American Literature

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Exceptional Vengeance: Revenge and the Rule of Law in Nineteenth-Century American Literature A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Lisa M. Thomas Committee in charge: Professor Nicole Tonkovich, Chair Professor John Blanco Professor Michael Davidson Professor Rachel Klein Professor Shelley Streeby 2012 Copyright Lisa M. Thomas, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Lisa M. Thomas is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION To my family, friends, and committee for their endless encouragement, support, and patience. Whatever happens next, thanks for coming along (and putting up) with me. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………........ iii Dedication…………………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………….. v Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………… vi Vita ………………………………………………………………………………… vii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………. viii Introduction: Revenge, Justice, and Exceptionalist Rhetoric in the Nineteenth-Century United States………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 1: Reluctant Warriors: Community and Conflict in William Gilmore Simms’s The Yemassee ……………………………………………………… 51 Chapter 2: Unlikely Killers: Justifying Violence against Native Americans through Hannah Duston’s Captivity and Nick of the Woods ……………….. 125 Chapter 3: Revenge and Regret on the Texas