Existing Conditions and Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Best Beaches South of San Francisco

California’s Best Beaches South of San Francisco Author’s Note: This article “California’s Best Beaches South of San Francisco” is one of 30 chapters in my book/ebook Northern California Travel: The Best Options. That book is available in English as a book/ebook and also as an ebook in Chinese. Several of my books on California can be seen on myAmazon Author Page. See also my companion article “California’s Best Beaches North of San Francisco.” By Lee Foster If headed south from San Francisco on CA Highway 1, which are the loveliest beaches at which to linger? Here are my suggestions: Montara Beach, 10 miles south Montara Beach offers a classic beach experience and is my favorite in this region. You park on a bluff overlooking the south end of the beach. Stretching in front of you are a couple miles of sand, going north. The lookout is inviting. The beach is wide and welcoming. The surf is crashing. In the hours before sunset a golden glow from the west settles on the beach and cliffs behind it. Gingerly descend the stairs to the beach. The stairs get wiped out from time to time by storms. But then they get rebuilt. Walk north along the beach. Admire the thunderous surf. Gulp in the fresh air. Accept the glow of the sun from the west. Indulge in a near-wilderness experience, yet very close to San Francisco. A very few other people will be frolicking on the beach, perhaps with their dogs fetching sticks in the surf. -

Map Showing Seacliff Response to Climatic And

MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES MF-2399 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY C A 123 122 30' 122 LI 38 FO Table 1. Linear extent of cliff section experiencing slope failure for each of the time periods investigated. The data is further subdivided to Concord Map RN show the type of slope failure for each occurrence, as well as the geologic units involved, if distinguishable. Area INTRODUCTION I A The coastal cliffs along much of the central California coast are actively retreating. Large storms and periodic GULF OF THE earthquakes are responsible for most of the documented seacliff slope failures. Long-term average erosion rates calculated for FARALLONES Debris Debris this section of coast (Moore and others, 1999) do not provide the spatial or temporal data resolution necessary to identify the Time Interval BlBlock k OthOther TtTotalll along-cliffliff NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Oakland processes responsible for retreat of the seacliffs, where episodic retreat threatens homes and community infrastructure. falls flows Slumps (m) Slaking (m) San fll(falls (m) ) ()(m) filfailure per itinterval l Francisco Research suggests that more erosion occurs along the California coast over a short time scale, during periods of severe storms (m) (m) Farallon or seismic activity, than occurs during decades of normal weather or seismic quiescence (Griggs and Scholar, 1998; Griggs, Islands 1994; Plant and Griggs, 1990; Griggs and Johnson, 1979 and 1983; Kuhn and Shepard, 1979). Livermore This is the second map in a series of maps documenting the processes of short-term seacliff retreat through the 0 130130.5 5 113113.4 4 identification of slope failure styles, spatial variability of failures, and temporal variation in retreat amounts in an area that has --------- 0 0 ------------- 0 0 243.9 Pacifica (i(instantaneous) t t ) been identified as an erosion hotspot (Moore and others, 1999; Griggs and Savoy, 1985). -

Annex 18 Santa Clara County Parks and Recreation Department

Santa Clara County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Annex 18 – County of Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department ANNEX 18. COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA PARKS AND RECREATION DEPARTMENT Prepared by: Flint Glines, Seth Hiatt, Don Rocha, John Patterson, and Barry Hill Santa Clara County acquired its first parkland in 1924, purchasing 400 acres near Cupertino, which became Stevens Creek County Park. In 1956, the Department of Parks and Recreation was formed. Currently, the regional parks system has expanded to 29 parks encompassing nearly 48,000 acres. Santa Clara County Parks and Recreation Department (County Parks) provides a sustainable system of diverse regional parks, trails, and natural areas that connects people with the natural environment, and supports healthy lifestyles, while balancing recreation opportunities with the protection of natural, cultural, historic, and scenic resources (https://www.sccgov.org/sites/parks/AboutUs/Pages/About-the-County-Regional-Parks.aspx). County Parks are regional parks located close to home, yet away from the pressures of the valley’s urban lifestyle. The parks offer opportunities for recreation in a natural environment to all County residents. Regional parks are larger in size, usually more than 200 acres, than local neighborhood or community parks. Many of the County’s regional parks also feature points of local historic interest. County park locations are shown in Figure 18.1. SWCA Environmental Consultants 1 August 2016 Santa Clara County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Annex 18 – County of Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department Figure 18.1. County park locations. SWCA Environmental Consultants 2 August 2016 Santa Clara County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Annex 18 – County of Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department ORGANIZATION AND JURISDICTION Santa Clara County Parks is governed by the Board of Supervisors. -

Pitch Canker Kills Pines, Spreads to New Species and Regions

Pitch canker kills pines, Page 1 of 8 Return to Previous Page Pitch canker kills pines, spreads to new species and regions Andrew J. Storer o Thomas R. Gordon o Paul L. Dallara o David L. Wood California Agriculture, Vol. 48, No. 6, pages 9-13 The host and geographic range of the pitch canker pathogen has greatly increased since it was first discovered in California in 1986. Most significantly, it now affects many pine species, including native stands of Monterey pine, and has made a transgeneric jump to Douglas fir. Isolated occurrences of the disease have been found as far north as Mendocino County. Insects are strongly implicated as vectors of the pathogen, and long term management appears to be dependent on the development of resistant tree varieties. In infested regions, the planting of Monterey pine and other pine tree species should be undertaken with caution. Pitch canker disease was first identified in California at New Brighton State Beach, Santa Cruz County, in 1986. By the beginning of 1992, it was recorded as far north as San Francisco and as far south as San Diego County. Most records were from Monterey pine, but occasional infections of bishop, Coulter, Italian stone, Aleppo, ponderosa and Canary Island pine were reported. The most extensive infestations were in Santa Cruz and southern Alameda counties. In Southern California, with the exception of an isolated infestation in Santa Barbara County, only Monterey pine Christmas tree plantations were affected. Pitch canker disease, caused by the fungus Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini, is characterized by a resinous exudation on the surface of Trees with advanced pich canker symptoms have significant crown shoots, branches, exposed roots and boles of dieback due to the large number of infested trees. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

2011 Progress Report Full Version 02 12.Indd

CALIFORNIA RECREATIONAL TRAILS PLAN Providing Vision and Direction for California Trails Tahoe Rim Trail Tahoe Rim Trail TahoeTTahhoe RRiRimm TrailTTrail Complete Progress Report 2011 California State Parks Planning Division Statewide Trails Section www.parks.ca.gov/trails/trailsplan Message from the Director Th e ability to exercise and enjoy nature in the outdoors is critical to the physical and mental health of California’s population. Trails and greenways provide the facilities for these activities. Our surveys of Californian’s recreational use patterns over the years have shown that our variety of trails, from narrow back-country trails to spacious paved multi-use facilities, provide experiences that attract more users than any other recreational facility in California. Th e increasing population and desire for trails are increasing pressures on the agencies charged with their planning, maintenance and management. As leaders in the planning and management of all types of trail systems, California State Parks is committed to assisting the state’s recreation providers by complying with its legislative mandate of recording the progress of the California Recreational Trails Plan. During the preparation of this progress report, input was received through surveys, two California Recreational Trails Committee public meetings and a session at the 2011 California Trails and Greenways Conference. Preparation of this progress Above: Director Ruth Coleman report included extensive research into the current status of the 27 California Trail Corridors, determining which of these corridors need administrative, funding or planning assistance. Research and public input regarding the Plan’s twelve Goals and their associated Action Guidelines have identifi ed both encouraging progress and areas where more attention is needed. -

Santa Cruz County Parks Strategic Plan Appendix 1

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY PARKS STRATEGIC PLAN APPENDIX 1 ParkScore® Index for the County of Santa Cruz, California Prepared by the Trust for Public Land November, 2017 As the leading U.S. organization that works to analyze and determine the value of urban parks, The Trust for Public Land has created a methodology to give a general rating of every major U.S. city’s park system through its proprietary program called ParkScore®. Santa Cruz County has a total population of 274,780 in 2017.1 It is located in the mid-coast of California at the north end of the Monterey Bay. The county is 285,522 acres2 making the density a little under 1 person per acre (0.96 people/acre). Of that acreage, 51,776 acres, or 18.1%, of Santa Cruz County are publically accessible parks, parkland, or open space. The county includes four incorporated municipalities. These are the cities of Capitola, Santa Cruz, Scotts Valley, and Watsonville (Table 1). Table 1. Incorporated cities of Santa Cruz County and populations City Population3 Capitola 10,180 Santa Cruz 64,465 Scotts Valley 11,928 Watsonville 53,796 Each of these municipalities operate parks, recreation Table 2. Parks, recreation, and open space amenities provided in facilities, or open space of their own. In addition, there Santa Cruz County are four special recreation and park districts in unincorporated areas that provide different combinations of these services (Table 2). These are independent of city and county governments and are governed by a board of directors.4 Parkland in the unincorporated part of the county is managed by the Santa Cruz County Department of Parks, Open Space, and Cultural Services. -

Early Life 1 Berkeley, California 6 World War II 13 Japanese

Early Life 1 Berkeley, California 6 World War II 13 Japanese-American Internment 15 World War II 18 Harvard Business School 23 Ford’s Department Store, Watsonville, California 26 Watsonville in the 1950s 28 Agriculture in the Pajaro Valley 31 H.A. Hyde Company Growers and Nurserymen 34 North and South Santa Cruz County 36 The Founding of Cabrillo Community College 48 Founding the University of California, Santa Cruz 70 Early Appointments 80 Campus Organization 88 Boards of Studies 89 Francis H. Clauser 92 Lick Observatory 92 Affirmative Action 95 Academic Planning 103 The Demise of Professional Schools 109 Business School 111 Dean E. McHenry’s Retirement 112 Student Activism 117 Campus Infrastructure Planning 122 The Legacy of Dean E. McHenry 128 UC Santa Cruz Foundation 129 Other UCSC Chancellors 131 The Loma Prieta Earthquake of October 17, 1989 135 Cultural Life in Santa Cruz County 139 Cultural Council of Santa Cruz County 142 Henry J. Mello Center for the Performing Arts 144 Persis Horner Hyde 150 The University Library 158 UCSC Arboretum 162 Alan Chadwick and the UCSC Farm and Garden Project 164 Harold A. Hyde: Early Life page 1 Early Life Jarrell: To start, where and when were you born? Hyde: I was born in Watsonville Hospital, in Watsonville, California, on Third Street downtown, on May 5, 1923. Jarrell: Tell me something about your origins, your family, your mother and father. Hyde: I really am fortunate that all my forebears came to live in the Santa Cruz area in the 19th century. I am the product of that. -

Seacliff & New Brighton State Beaches

Our Mission Seacliff & The mission of California State Parks is to provide for the health, inspiration and ong stretches of bluff- education of the people of California by helping L to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological New Brighton diversity, protecting its most valued natural and backed sandy beaches cultural resources, and creating opportunities State Beaches for high-quality outdoor recreation. invite visitors to play on the beach, watch a glorious sunset, or stroll peacefully along the shore. California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the park at (831) 685-6500. If you need this publication in an alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Seacliff State Beach 201 State Park Drive, Aptos, CA 95003 (831) 685-6500 New Brighton State Beach Park Avenue off Hwy. 1, Capitola, CA 95010 (831) 464-6329 © 2002 California State Parks (Rev. 2016) A t Seacliff State Beach, a thwarting future plans for mile-long expanse of soft sand expansion. Today, the stripped, connects this popular recreation abandoned SS Palo Alto is unsafe spot with New Brighton State Beach, and closed to the public, as is where wooded bluffs provide part of the pier near the ship. unparalleled views of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. NEW BRIGHTON STATE BEACH SS Palo Alto In the 1850s, Thomas Fallon AREA HISTORY acquired part of Rancho Soquel years, beachfront camping, picnicking, The Ohlone Indians thrived for thousands and turned it into a resort he named New fishing, and interpretive walks have been of years on the area’s natural resources. -

Waterfall Hikes

Waterfall Hikes of the Peninsula and South Bay HIKE LOCATIONS PROTECTED LAND COUNTY, STATE, AND NATIONAL PARKS, REGIONAL PRESERVES, AND POSTPROTECTED LAND Berry Creek Falls Big Basin Redwoods State Park 1 MILEAGE 9.5 MILE LOOP ELEVATION 3,200 FT SEASON ALL YEAR ROUTE FROM THE PARK HEADQUARTERS, FOLLOW THE SUNSET TRAIL TO THE BERRY CREEK FALLS TRAIL AND SKYLINE TO SEA TRAIL Big Basin is home to some of the biggest trees and waterfalls in the Santa Cruz Mountains. In the late spring, listen carefully for endangered marbled murrelets nesting near this waterfall. Trail Map Back to Map Gnissah 2011 POST protects and cares for open space, farms, and parkland in and around Silicon Valley. www.openspacetrust.org Tiptoe Falls Pescadero Creek County Park 2 MILEAGE 1.2 MILES ROUND TRIP ELEVATION 500 FT SEASON WINTER, SPRING ROUTE FROM THE PARK HEADQUARTERS, FOLLOW PORTOLA STATE PARK ROAD TO TIPTOE FALLS TRAIL. RETRACE YOUR STEPS This short and relatively easy trail to Tiptoe Falls makes this hike enjoy- able for the whole family. You’ll find this waterfall on Fall Creek - a short, steep tributary of Pescadero Creek. Trail Map Visit Preserve Back to Map Aleksandar Milovojevic 2011 POST protects and cares for open space, farms, and parkland in and around Silicon Valley. www.openspacetrust.org Kings Creek Falls Castle Rock State Park 3 MILEAGE 3 MILE LOOP ELEVATION 1,110 FT SEASON WINTER, SPRING ROUTE FROM SKYLINE BLVD, FOLLOW THE SARATOGA GAP TRAIL TO THE INTERCONNECTOR TRAIL AND RIDGE TRAIL The tranquility found at Kings Creek Falls is just one of the many treasures found at Castle Rock State Park. -

W • 32°38'47.76”N 117°8'52.44”

public access 32°32’4”N 117°7’22”W • 32°38’47.76”N 117°8’52.44”W • 33°6’14”N 117°19’10”W • 33°22’45”N 117°34’21”W • 33°45’25.07”N 118°14’53.26”W • 33°45’31.13”N 118°20’45.04”W • 33°53’38”N 118°25’0”W • 33°55’17”N 118°24’22”W • 34°23’57”N 119°30’59”W • 34°27’38”N 120°1’27”W • 34°29’24.65”N 120°13’44.56”W • 34°58’1.2”N 120°39’0”W • 35°8’54”N 120°38’53”W • 35°20’50.42”N 120°49’33.31”W • 35°35’1”N 121°7’18”W • 36°18’22.68”N 121°54’5.76”W • 36°22’16.9”N 121°54’6.05”W • 36°31’1.56”N 121°56’33.36”W • 36°58’20”N 121°54’50”W • 36°33’59”N 121°56’48”W • 36°35’5.42”N 121°57’54.36”W • 37°0’42”N 122°11’27”W • 37°10’54”N 122°23’38”W • 37°41’48”N 122°29’57”W • 37°45’34”N 122°30’39”W • 37°46’48”N 122°30’49”W • 37°47’0”N 122°28’0”W • 37°49’30”N 122°19’03”W • 37°49’40”N 122°30’22”W • 37°54’2”N 122°38’40”W • 37°54’34”N 122°41’11”W • 38°3’59.73”N 122°53’3.98”W • 38°18’39.6”N 123°3’57.6”W • 38°22’8.39”N 123°4’25.28”W • 38°23’34.8”N 123°5’40.92”W • 39°13’25”N 123°46’7”W • 39°16’30”N 123°46’0”W • 39°25’48”N 123°25’48”W • 39°29’36”N 123°47’37”W • 39°33’10”N 123°46’1”W • 39°49’57”N 123°51’7”W • 39°55’12”N 123°56’24”W • 40°1’50”N 124°4’23”W • 40°39’29”N 124°12’59”W • 40°45’13.53”N 124°12’54.73”W 41°18’0”N 124°0’0”W • 41°45’21”N 124°12’6”W • 41°52’0”N 124°12’0”W • 41°59’33”N 124°12’36”W Public Access David Horvitz & Ed Steck In late December of 2010 and early Janu- Some articles already had images, in which ary of 2011, I drove the entire California I added mine to them. -

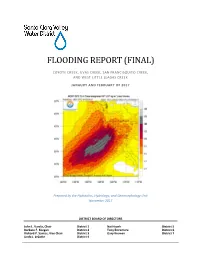

2017 Flood Report

FLOODING REPORT (FINAL) COYOTE CREEK, UVAS CREEK, SAN FRANCISQUITO CREEK, AND WEST LITTLE LLAGAS CREEK JANAURY AND FEBRUARY OF 2017 Prepared by the Hydraulics, Hydrology, and Geomorphology Unit November 2017 DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS John L. Varela, Chair District 1 Nai Hsueh District 5 Barbara F. Keegan District 2 Tony Estremera District 6 Richard P. Santos, Vice Chair District 3 Gary Kremen District 7 Linda J. LeZotte District 4 CONTENTS WINTER SEASON SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 JANUARY 6TH THRU 9TH STORM ..................................................................................................................... 2 OVERVIEW & WEATHER ................................................................................................................................ 2 FLOODING – JANUARY 8th ............................................................................................................................. 4 UVAS CREEK .............................................................................................................................................. 4 WEST LITTLE LLAGAS CREEK ...................................................................................................................... 6 FEBRUARY 6th AND 7th STORM ...................................................................................................................... 9 OVERVIEW & WEATHER ...............................................................................................................................