Crop Profile for Satsuma Mandarin in Alabama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Performance of Citrus Scion Cultivars and Rootstocks in a High-Density

REPORTS HORTSCIENCE 26(7):837-840. 1991. house and planted in the field in 1981. A split plot experiment and analysis of variance Performance of Citrus Scion Cultivars (ANOVA) statistics were used with four rep- lications, with cultivar as the main plot and and Rootstock in a High-density rootstock as the subplot. Field plots were four ´ four trees, with data taken from the Planting center four of the 16 trees. They were planted 1.5 m in the row and 3.3 m between rows T.A. Wheaton, W.S. Castle, J.D. Whitney, and D.P.H. Tucker and were irrigated and fertigated as required Citrus Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Institute of to maintain optimal soil water and nutrient levels using one microsprinkler per two trees. Food and Agricultural Sciences, 700 Experiment Station Road, Lake Trees were mechanically hedged and topped Alfred, FL 33850 during Summer 1987 and hedged again in 1989 to maintain a 1.5-m alley between rows Additional index words. tree spacing, yield efficiency and a 2.5-m tree height. Thus, the canopy Abstract. ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ oranges [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osb.], ‘Murcott’ tangor size allocated for each tree was 1.5 m in the (C. reticulata Blanco ´ C. sinensis), and ‘Redblush’ grapefruit (C. paradisi Macf.) on row, 1.8 m across the row, and 2.5 m in 15 rootstock and own-rooted cuttings were planted at a 1.5 ´ 3.3-m spacing providing height, providing 6.8 m3 of canopy volume a density of 2020 trees/ha. -

Known Host Plants of Huanglongbing (HLB) and Asian Citrus Psyllid

Known Host Plants of Huanglongbing (HLB) and Asian Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina Liberibacter citri Plant Name asiaticus Citrus Huanglongbing Psyllid Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. Serr.: bael, Bengal quince, golden apple, bela, milva X Aeglopsis chevalieri Swingle: Chevalier’s aeglopsis X X Afraegle gabonensis (Swingle) Engl.: Gabon powder-flask X Afraegle paniculata (Schum.) Engl.: Nigerian powder- flask X Atalantia missionis (Wall. ex Wight) Oliv.: see Pamburus missionis X X Atalantia monophylla (L.) Corr.: Indian atalantia X Balsamocitrus dawei Stapf: Uganda powder- flask X X Burkillanthus malaccensis (Ridl.) Swingle: Malay ghost-lime X Calodendrum capense Thunb.: Cape chestnut X × Citroncirus webberi J. Ingram & H. E. Moore: citrange X Citropsis gilletiana Swingle & M. Kellerman: Gillet’s cherry-orange X Citropsis schweinfurthii (Engl.) Swingle & Kellerm.: African cherry- orange X Citrus amblycarpa (Hassk.) Ochse: djerook leemo, djeruk-limau X Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle: lime, Key lime, Persian lime, lima, limón agrio, limón ceutí, lima mejicana, limero X X Citrus aurantium L.: sour orange, Seville orange, bigarde, marmalade orange, naranja agria, naranja amarga X Citrus depressa Hayata: shiikuwasha, shekwasha, sequasse X Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck: see Citrus maxima X Citrus hassaku hort. ex Tanaka: hassaku orange X Citrus hystrix DC.: Mauritius papeda, Kaffir lime X X Citrus ichangensis Swingle: Ichang papeda X Citrus jambhiri Lushington: rough lemon, jambhiri-orange, limón rugoso, rugoso X X Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka: xiang -

Marketing Standards for Citrus Fruits

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 543/2011 of 7 June 2011 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 in respect of the fruit and vegetables and processed fruit and vegetables sectors. CONSOLIDATED TEXT: Annex I; Part 2 of Part B MARKETING STANDARD FOR CITRUS FRUIT I. DEFINITION OF PRODUCE This standard applies to citrus fruit of varieties (cultivars) grown from the following species, to be supplied fresh to the consumer, citrus fruit for industrial processing being excluded: - lemons grown from the species Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. and hybrids thereof, - mandarins grown from the species Citrus reticulata Blanco, including satsumas (Citrus unshiu Marcow), clementines (Citrus clementina hort. ex Tanaka), common mandarins (Citrus deliciosa Ten.) and tangerines (Citrus tangerina Tanaka) grown from these species and hybrids thereof, - oranges grown from the species Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck and hybrids thereof. II. PROVISIONS CONCERNING QUALITY The purpose of the standard is to define the quality requirements for citrus fruit after preparation and packaging. However, at stages following dispatch products may show in relation to the requirements of the standard: - a slight lack of freshness and turgidity, - for products graded in classes other than the “Extra” Class, a slight deterioration due to their development and their tendency to perish. A. Minimum requirements In all classes, subject to the special provisions for each class and the tolerances allowed, the citrus fruit must be: - intact, - free of bruising and/or extensive healed overcuts, CI.1 - sound; produce affected by rotting or deterioration such as to make it unfit for consumption is excluded, - clean, practically free of any visible foreign matter, - practically free from pests, - free from damage caused by pests affecting the flesh, - free of signs of shrivelling and dehydration, - free of damage caused by low temperature or frost, - free of abnormal external moisture, - free of any foreign smell and/or taste. -

Known Host Plants of Huanglongbing (HLB) and Asian Citrus Psyllid

Known Host Plants of Huanglongbing (HLB) and Asian Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina Liberibacter citri Plant Name asiaticus Citrus Huanglongbing Psyllid Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. Serr.: bael, Bengal quince, golden apple, bela, milva X Aeglopsis chevalieri Swingle: Chevalier’s aeglopsis X X Afraegle gabonensis (Swingle) Engl.: Gabon powder-flask X Afraegle paniculata (Schum.) Engl.: Nigerian powder- flask X Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.: jackfruit, jack, jaca, árbol del pan, jaqueiro X Atalantia missionis (Wall. ex Wight) Oliv.: see Pamburus missionis X X Atalantia monophylla (L.) Corr.: Indian atalantia X Balsamocitrus dawei Stapf: Uganda powder- flask X X Burkillanthus malaccensis (Ridl.) Swingle: Malay ghost-lime X Calodendrum capense Thunb.: Cape chestnut X × Citroncirus webberi J. Ingram & H. E. Moore: citrange X Citropsis gilletiana Swingle & M. Kellerman: Gillet’s cherry-orange X Citropsis schweinfurthii (Engl.) Swingle & Kellerm.: African cherry- orange X Citrus amblycarpa (Hassk.) Ochse: djerook leemo, djeruk-limau X Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle: lime, Key lime, Persian lime, lima, limón agrio, limón ceutí, lima mejicana, limero X X Citrus aurantium L.: sour orange, Seville orange, bigarde, marmalade orange, naranja agria, naranja amarga X Citrus depressa Hayata: shiikuwasha, shekwasha, sequasse X Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck: see Citrus maxima X Citrus hassaku hort. ex Tanaka: hassaku orange X Citrus hystrix DC.: Mauritius papeda, Kaffir lime X X Citrus ichangensis Swingle: Ichang papeda X Citrus jambhiri Lushington: rough lemon, jambhiri-orange, limón rugoso, rugoso X X Citrus junos Sieb. ex Tanaka: xiang cheng, yuzu X Citrus kabuchi hort. ex Tanaka: this is not a published name; could they mean Citrus kinokuni hort. ex Tanaka, kishu mikan? X Citrus limon (L.) Burm. -

High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citrus Waste with Non-Conventional Methods

foods Review High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citrus Waste with Non-Conventional Methods Mayra Anticona, Jesus Blesa , Ana Frigola and Maria Jose Esteve * Nutrition and Food Chemistry, University of Valencia, Avda., Vicent Andrés Estellés, s/n., 46100 Burjassot, Spain; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (A.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-963544913 Received: 27 April 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 20 June 2020 Abstract: Citrus fruits are extensively grown and much consumed around the world. Eighteen percent of total citrus cultivars are destined for industrial processes, and as a consequence, large amounts of waste are generated. Citrus waste is a potential source of high biological value compounds, which can be used in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries but whose final disposal may pose a problem due to economic and environmental factors. At the same time, the emerging need to reduce the environmental impact of citrus waste and its responsible management has increased. For these reasons, the study of the use of non-conventional methods to extract high biological value compounds such as carotenoids, polyphenols, essential oils, and pectins from this type of waste has become more urgent in recent years. In this review, the effectiveness of technologies such as ultrasound assisted extraction, microwave assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, pressurized water extraction, pulsed electric field, high-voltage electric discharges, and high hydrostatic pressures is described and assessed. A wide range of information concerning the principal non-conventional methods employed to obtain high-biological-value compounds from citrus waste as well as the most influencing factors about each technology are considered. -

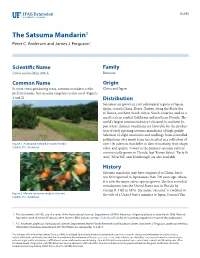

The Satsuma Mandarin1 Peter C

HS195 The Satsuma Mandarin1 Peter C. Andersen and James J. Ferguson2 Scientific Name Family Citrus unshiu Marcovitch Rutaceae Common Name Origin In most citrus producing areas, satsuma mandarin is the China and Japan preferred name, but satsuma tangerine is also used (Figures 1 and 2). Distribution Satsumas are grown in cool subtropical regions of Japan, Spain, central China, Korea, Turkey, along the Black Sea in Russia, southern South Africa, South America, and on a small scale in central California and northern Florida. The world’s largest satsuma industry is located in southern Ja- pan where climatic conditions are favorable for the produc- tion of early ripening satsuma mandarins of high quality. Selection of slight mutations and seedlings from controlled pollinations over many years has resulted in a collection of Figure 1. A satsuma orchard in north Florida. over 100 cultivars that differ in date of maturity, fruit shape, Credits: P. C. Andersen color, and quality. ‘Owari’ is the primary satsuma cultivar commercially grown in Florida, but ‘Brown Select’, ‘Early St. Ann’, ‘Silverhill’, and ‘Kimbrough’ are also available. History Satsuma mandarin may have originated in China, but it was first reported in Japan more than 700 years ago, where it is now the major citrus species grown. The first recorded introduction into the United States was in Florida by George R. Hall in 1876. The name “satsuma” is credited to Figure 2. Mature satsumas ready for harvest. the wife of a United States minister to Japan, General Van Credits: P. C. Andersen 1. This document is HS195, one of a series of the Horticultural Sciences Department, UF/IFAS Extension. -

Citrus Unshiu Extract

ORYZA OIL & FAT CHEMICAL CO., LTD. CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT Health Ingredient for prevention of osteoporosis Health Ingredient for whitening and aesthetic Ingredient for cosmetics CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT-P (Powder, Food Grade) CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT-L (Liquid, Food Grade) CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT-PC (Powder, Cosmetic Grade) CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT-LC (Liquid, Cosmetic Grade) ORYZA OIL&FAT CHEMICAL CO., LTD. Ver.3.0HS ver. 2.0SJ CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT ver.3.0HS CITRUS UNSHIU EXTRACT Health Ingredient for the prevention of osteoporosis Health Ingredient for whitening and aesthetic Ingredient for cosmetics 1. Introduction Advancement in science & technology and higher standard of living have significantly increased life expectancy in human. Japan is the nation with the highest longevity in the world. However, incidence of osteoporosis increases with increasing life expectancy among the aged population. Osteoporosis is a major and growing public health concern especially for older women and men. Incidence of post-menopausal osteoporosis is high in women aged 50 and above and is classified as primary osteoporosis. More than 90% post-menopausal women are diagnosed with osteoporosis. Risk for dementia increases as complications of osteoporosis related bed-ridden condition Osteoporosis, or porous bone, is a disease characterized by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to bone fragility and an increased susceptibility to fractures of the hip, spine and wrist. Men as well as women suffer from osteoporosis, a disease that can be prevented and treated. Osteoporosis is a multifactorial disease and is influenced by factors like nutritions, hormone and physical activity. The process of bone resorption and reformation is continuous and osteoclasts are important in the regulation of bone metabolism. -

List of Citrus Fruits

Common Taxonomic SNo Notes name(s) name/constituents Yellowish-orange in colour, about the size of grapefruit and oblate in shape. 1 Amanatsu Citrus natsudaidai The fruit contains 12 segments and about 30 seeds. Balady citron 2 Palestinian Citrus medica Grown in Israel and used for Jewish ritual purposes. citron Bergamot 3 Citrus bergamia orange Bitter orange Seville orange Sour orange 4 Bigarade Citrus × aurantium orange Marmalade orange 5 Blood orange Citrus × sinensis Buddha's hand Citrus medica var. 6 Bushukan sarcodactylis Fingered citron Calamondin × Citrofortunella 7 Calamansi mitis Citrus reticulata × 8 Cam sành maxima 9 Citron Citrus medica Citrus subg. Papeda indicates the subgenus Papeda of the genus Citrus, with citrus species native to Asia.The papeda group includes some of the most Citrus subg. tropical, and also some of the most frost-tolerant citrus plants. They are 10 Papeda cultivated far less often than other citrus, though they will all hybridize with other citrus. This group contains about 15 species. 11 Clementine Citrus reticulata Corsican 12 citron Found in lowland subtropical rainforest and dry rainforest areas of Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. Early settlers consumed the 13 Desert Lime Citrus glauca fruit and retained the trees when clearing for agriculture. Commercial uses include boutique marmalade and restaurant dishes, and is exported for such. 14 Etrog Citrus medica The finger lime has been recently popularised as a gourmet bushfood. 15 Finger lime Citrus australasica Finger lime is thought to -

CITRUS the Botanictanic Garden of the Universitat De València

Botanical monographs CITRUS The Botanictanic Garden of the Universitat de València Gema Ancillo Alejandro Medina Botanical Monographs CITRUS Gema Ancillo and Alejandro Medina Botanical Monographs. Jardín Botánico de la Universitat de València Volume 2: Citrus Texts ©: Gema Ancillo and Alejandro Medina Introduction ©: Isabel Mateu Images and illustrations ©: Gema Ancillo, Alejandro Medina and José Plumed Publication ©: Universitat de València E. G. Director of the monographic series: Isabel Mateu Technical director: Martí Domínguez Graphic design and layout: José Luis Iniesta Revision and correction: José Manuel Alcañiz Translation: Fabiola Barraclough, Interglobe Language Photographs: José Plumed, Gema Ancillo, Alejandro Medina, Miguel Angel Ortells and José Juarez Cover photograph: Miguel Angel Ortells Printed by: Gráfi cas Mare Nostrum, S. L. Legal Deposit: V-439-2015 ISBN: 978-84-370-9632-2 Index Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 The Aurantioideae Subfamily....................................................................................................11 – General description ...............................................................................................................................11 – Trunk ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 – Roots .....................................................................................................................................................13 -

Quali-Quantitative Profile of Native Carotenoids in Kumquat from Brazil

foods Article Quali-Quantitative Profile of Native Carotenoids in Kumquat from Brazil by HPLC-DAD-APCI/MS Helena Maria Pinheiro-Sant’Ana 1, Pamella Cristine Anunciação 1 , Clarice Silva e Souza 1, Galdino Xavier de Paula Filho 2, Andrea Salvo 3,*, Giacomo Dugo 3 and Daniele Giuffrida 3 1 Departamento de Nutrição e Saúde, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Avenida P.H. Rolfs, s/n, Viçosa 36571-000, Brazil; [email protected] (H.M.P.-S.); [email protected] (P.C.A.); [email protected] (C.S.e.S.) 2 Departamento de Educação, Universidade Federal do Amapá, Rodovia Juscelino Kubitschek, Km 02, Jardim Marco Zero, Macapá 68903-419, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Department, of Biomedical and Dental Sciences and Morphofunctional Imaging, University of Messina (Italy), V.le Annunziata, 98168 Messina, Italy; [email protected] (G.D.); dgiuff[email protected] (D.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-090-676-6880 Received: 3 April 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 16 May 2019 Abstract: In this study the native carotenoids composition in kumquat (Fortunella margarita) (peel + pulp) from Brazil was determined for the first time by a HPLC-DAD-APCI/MS (high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detector-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/mass spectrometry), methodology. Eleven carotenoids were successfully identified and quantified in kumquat: four carotenoids in the free form and seven carotenoids in the esterified form. β-citraurin-laurate was the carotenoid found in the highest content (607.33 µg/100 g fresh matter), followed by β-cryptoxanthin-laurate (552.59 µg/100 g). The different esterified forms of β-citraurin and β-cryptoxanthin represented 84.34% of the carotenoids found, which demonstrates the importance of esterification in natural fruits. -

United Nations

ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/GE.1/2015/INF.6 15 April 2015 Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Trade Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards Specialized Section on Standardization of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Sixty-third session Geneva, 21-24 April 2015 Item 5 (a) of the provisional agenda Revision of UNECE standards Revision of UNECE standards - Citrus fruit Comments by the delegation of South Africa The following comments were submitted by the delegation of South Africa. I. Definition of produce1 This standard applies to the following varieties (cultivars) of fruit, classified as “citrus fruit”, to be supplied fresh to the consumer, citrus fruit for industrial processing being excluded: • lemons grown from the species Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. and hybrids thereof • Persian limes grown from the species Citrus latifolia (Yu. Tanaka) Tanaka, a large- fruited acid lime known also as Bearss or Tahiti and hybrids thereof • Mexican limes grown from the species Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle, also known as key limes and sour limes and hybrids thereof • Indian sweet limes, Palestine sweet limes grown from the species Citrus limettioides Tanaka • mandarins (Citrus reticulata Blanco), including satsumas (Citrus unshiu Marcow.), clementines (Citrus clementina hort. ex Tanaka), common mandarins (Citrus deliciosa Ten.) and tangerines (Citrus tangerina Tanaka), grown from these species and hybrids thereof • oranges grown from the species Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck and hybrids thereof • grapefruit grown from the species Citrus paradisi Macfad. and hybrids thereof • pummelos or Shaddock grown from the species Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. and hybrids thereof. 1 All information on botanical names is taken from the GRIN database. -

Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis Capitata, Host List the Berries, Fruit, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for C

January 2017 Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, Host List The berries, fruit, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for C. capitata. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of C. capitata. Scientific Name Common Name Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret Pineapple guava Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd Bushman's poison Acokanthera schimperi (A. DC.) Benth. & Hook. f. ex Schweinf. Arrow poison tree Actinidia chinensis Planch Golden kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa (A. Chev.) C. F. Liang & A. R. Ferguson Kiwifruit Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew1 Annona cherimola Mill. Cherimoya Annona muricata L. Soursop Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona senegalensis Pers. Wild custard apple Antiaris toxicaria (Pers.) Lesch. Sackingtree Antidesma venosum E. Mey. ex Tul. Tassel berry Arbutus unedo L. Strawberry tree Arenga pinnata (Wurmb) Merr. Sugar palm Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels Argantree Artabotrys monteiroae Oliv. N/A Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg Breadfruit Averrhoa bilimbi L. Bilimbi Averrhoa carambola L. Starfruit Azima tetracantha Lam. N/A Berberis holstii Engl. N/A Blighia sapida K. D. Koenig Akee Bourreria petiolaris (Lam.) Thulin N/A Brucea antidysenterica J. F. Mill N/A Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. Jelly palm, coco palm Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth Golden spoon Calophyllum inophyllum L. Alexandrian laurel Calophyllum tacamahaca Willd. N/A Calotropis procera (Aiton) W. T. Aiton Sodom’s apple milkweed Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. f. & Thomson Ylang-ylang Capparicordis crotonoides (Kunth) Iltis & Cornejo N/A Capparis sandwichiana DC. Puapilo Capparis sepiaria L. N/A Capparis spinosa L. Caperbush Capsicum annuum L. Sweet pepper Capsicum baccatum L.