Jesse M. Unruh Interviewer: Dennis O’Brien Date of Interview: June 18, 1969 Place of Interview: Sacramento, California Length: 15 Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre Rce Srategy: No Hel F,Mr

Statesman~~~~~~~~ .j6A PrI VOLUME 16 NUMBER 14 STONY BRkOOK. N.Y. ____ TU ESDAYI, OCTOB ER 31, 1972 Pre RCe Srategy: No Hel F,Mr By HOWIE BRANDSTEIN whole night to ponder such thoughts. What does a runner think about the night before In what Pat runner Ralph Egyud characterized .a race? Pre-race strategy, unlike the lengthy as something akin to the "high school cattle races" prepratins involved in something like football, is held weekly at Van Cortlandt Park, 140 "runners a relatively simple matter for the runner. from 17 schools were slated to go off at the gun '.'Know thyself, says Jim Smith, coach of the the following day at the Albany Invitationals. The Stony Brook cross country team. '"Run faster," five mile course, described in a brochure as "35% says Moe Davis, former track grioat. ma11cadam,. 65% 'dirt, gravel, and grass,"" gently It all comes down to the same thing, really. If winds around Albany's man-made pond in a figure' you're good, you're good (the opposite holds, too) eight. The campus itself - with its "Espider web" of and whether you plan to wear a Dave Wottle hat or spiraling arches and enormous symmetrical a -leopard-skin jock won't make any difference. quandrangles - is an interesting, if not surrealistic, And when the Patriots finally disembarked at a background for a race. hotel opposite the Albany campus, they had a (Continued on page 15), I (S(...To Set Lp A Bargaininas Group So That Students Can Get a Fair New York State Housing Contract." See Page' 5 Dorm Cooking Renovations Sow Efct *A STAGIOBNTONo apns disappo ntment was what Sandra Weeden's women's tenn's team team to victory. -

Carey Easily Beats Durye a GOP Takes Comptroller; Drops Attny

Carey Easily Beats Durye a GOP Takes Comptroller; Drops Attny. Gen. New York (AP)- by 56 percent to 44 Governor Hugh Carey percent. won a big re-election Republican Edward victory over challenger Regan, the Erie County Perry Duryea, the Montauk executive, appeared to have Assemblyman, yesterday, upset New York City defeating Republican efforts comptroller Harrison to turn the balloting into a Goldin in the race for state referendum over the death comptroller. Goldin led in penalty. New York City but trailed He hailed the large voter badly in the rest of the turnout across the state, state. and said that "this goes (See stories, page 7) against all the experts, who On the slate with Carey said there would be as the Democratic indifference, apathy and a candidate for lieutenant low vote." governor was Secretary of Duryea conceded just State Mario Cuomo; before midnight and said he Duryea's running mate on had sent a telegram to the Republican ticket was Carey, "I wish you well." United States With 42 percent of the Representative Bruce state's election districts Caputo of Yonkers. counted, it was Carey 56 Carey, a liberal by percent and Duryea 44 instinct, made fiscal 3 b ull kpv!rcAnnp nf hlr prlcnllt. otU.L)LercentD t AJLyLJ,,, oXV0uy l ·rpetr.int. county, Suffolk, opted for administration and his him by an overwhelming campaign stance. In the past 43,000 vote margin. two years he signed into law The voting produced the the first significant state tax ouster of one major figure cuts in 20 years, and he in state politics - Assembly boasted about a rate of Speaker Stanley Steingut, a growth in the state's budget Democrat, who lost in his which he said was well Brooklyn district. -

Jjt. Jnl}U' 5 1Fuiurrnity Alumni Nrwn

jJt. Jnl}u' 5 1fuiurrnity Alumni Nrwn TOLUME I, NU:MBER I FEBRUARY 1960 C.W.V. Honors ~Better Health' Then1e Of Msgr. Higgins 1960 Pharmacy Congress "It ls better to have biscuits than bullets, but when the time The 2nd Annual Congress for Pharmacists will be held at st. comes to fight for our liberties, John's University's College of Pharmacy on March 17, 1960, it tt will be found that we Catho has been announced by Dr. Andrew J. Bartilucci '44P, Dean of the Hcs are not afraid to die." College of Pharmacy. Alumni and those in the pharmaceutical field These words were spoken 21 are invited to broaden their knowledge and to share in a discussion years ago by the Right Rev. of problems facing the profession by participating in the aU-day Msgr. Edward J. Higgins, four symposium, Dr. Bartilucci added. years after he founded the The last Congress was an out- Catholic War Veterans. standing success and was at tended by leaders in the areas of Peter P. Smith, '95C Today these words are the Hospital Pharmacy, Community foundation of the CWV which Pharmacy, Industrial Pharmacy, State Court Justice, lists 70,000 members and 2,000 and Medical Detailing. The Com posts throughout the nation, in mittee is presently engaged in cluding 33 in Queens County. arranging an interesting program Dies on Feb. 2nd Understandably, the OWV held for the coming Congress which is Peter P. Smith '95C, retired its 25th anniversary convention one of St. John's University's State Supreme Court Justice, in its founder's home parish, at series of educational programs died Feb. -

Government, Law and Policy Journal

NYSBA SPRING 2010 | VOL. 12 | NO. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal A Publication of the New York State Bar Association Committee on Attorneys in Public Service, produced in cooperation with the Government Law Center at Albany Law School The New York State Constitution • When Is Constitutional Revision Constitutional Reform? • Overcoming Our Constitutional Catch-22 • The Budget Process • Proposals to Clarify Gubernatorial Inability to Govern and Succession • Ethics • More Voice for the People? • Gambling • Would a State Constitutional Amendment Promote Public Authority Fiscal Reform? • Liberty of the Community • Judging the Qualifications of the Members of the Legislature “I am excited that during my tenure as the Chair of the Committee on Attorneys in Public Service our Technology Subcommittee, headed by Jackie Gross and Christina Roberts-Ryba, with assistance from Barbara Beauchamp of the Bar Center, have developed a CAPs blog. This tool promises to be a wonderful way to communicate to CAPS Announces attorneys in public service items of interest New Blog for and by that they might well otherwise miss. Blogs Public Service Attorneys are most useful and attract the most NYSBA’s Committee on Attorneys in Public Service interest when they are (“CAPS”) is proud to announce a new blog highlighting current and updated interesting cases, legal trends and commentary from on a regular basis, and around New York State, and beyond, for attorneys our subcommittee is practicing law in the public sector context. The CAPS committed to making blog addresses legal issues ranging from government the CAPS blog among practice and public service law, social justice, the Bar Association’s professional competence and civility in the legal best! profession generally. -

HON. BROCK ADAMS to Change Her Assignment from a House Agri- Congressional Hopefuls

EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS- May 1, 1969 than ever a must lest the "taxpayers' revolt" get up there on the floor of Congress, I'm per cent black and 30 per cent white. become something more than a Walter Mitty sure you'll understand that I am speaking There were Puerto Ricans in Williams- dream. with the pent-up emotions of the commu- burg (Mrs. Chisholm speaks Spanish flu- nity'." She grinned. "One thing the people ently), Italians in the Bushwick section, in Washington and New York are afraid of and Jews in Crown Heights. Mrs. Chisholm's THIS IS FIGHTING SHIRLEY in Shirley Chisholm is HER MOUTH." The survey of the election rolls ("Before I make a CHISHOLM audience roared. move, I analyze everything," she says, eyes A few days later, Representative Chisholm snapping) turned up one additional demo- returned to Washington and began her fight graphic factor which possibly eluded other HON. BROCK ADAMS to change her assignment from a House Agri- Congressional hopefuls. The 12th had 10,000 OF WASHINGTON culture subcommittee on Forestry and Rural to 13,000 more registered women voters than IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Villages to something more relevant to her men. Before the ink was dry on the new dis- Bedford-Stuyvesant community. (Mrs. Chis- trict's lines; Shirley Chisholm put in her bid. Thursday, May 1, 1969 holm had hoped for Education and Labor.) While Bedford-Stuyvesant was the heart She approached Speaker John McCormack, of the new 12th Congressional District, the Mr. ADAMS. Mr. Speaker, it gives me who told her, she reports, to accept the as- Unity Democratic Club, the regular Demo- a great deal of pleasure to bring to the signment and "be a good soldier." She brood- cratic organization for the 55th State Assem- attention of the House an article on our ed'about that for a while, she says, and then bly District, was the strongest political club colleague the Honorable SHIRLEY CHIS- decided, "That's why the country is the way in Bedford-Stuyvesant. -

Your Help Needed Now on Abortion Legislation

YOUR HELP NEEDED NOW ON ABORTION LEGISLATION 0< Even before the opening of the 1971 session of the New Yol""k legislature, a number lots of letters--and we must show that we are wtlltng to work as hard as they of reactionary bills o n abortion h ave been filed, a nd influential support for these do to express our opini~But this doesn't mean that our letters have to be bills is being organized. Long o r elaborate- a quick, brief note is fine. So dash off a couple r ight now They include a bit I to exc tude abortion from 1\1\edicaid coverage , except when (use either the home addresses g iven here, or: NY State Capt tol, A lbany 12224). abortion is necessary to p r eserve life (introduced by Sen ator Don ovan, 44th Senate If you wonder what to say, here are some ideas that may he-lp: District); a bill to impose a 12-week time limit & a 90- day residency requirement, & a E ven if you don't say anything else, be sure to tell each legislator that you to limit abortions to hospitals or clinics, and to allow institutions & individuals to want him** not only to oppose all regressive abortion bills, but to co-sponsor refuse to provide abortio,, care (Griffin, 56 SD); bills to restore the old "necessary and to v..ork hard for the passage of the Ohrenstein-Le i. chter and von Luthe r- to preserve life" abortion taw (Donovan, 44 SD; Hausbeck, 144 AD; T. -

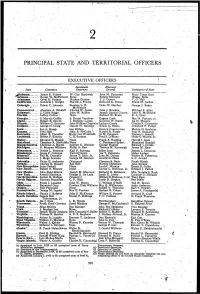

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

May 2013 Vol

MAY 2013 VOL. 85 | NO. 4 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Demystifying row Ethics Also in this Issue ESQ Electronic Health Records by Devika Kewalramani, at Trial Jason Canales and Michelle Cox Arbitration and Legal Research Developing a Law Practice Drafting for the Vacation Home NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Helping You Do More With More… > More advice via listserves > More networking opportunities with the best > More time and money savings on CLE “My very best NYSBA membership benefit is the listserves. By using the listserves, I can ask questions or bounce legal theories and strategies off my colleagues who are located near and far.” Simone N. Archer, NYSBA Member Since 2006 Archer Harvey & Smith, LLC New York, NY There are many ways in which the New York State Bar Association can help you develOP YOUR PROFESSIONAL SKILLS. With NYSBA Sections and Committees you can JOIN A LISTSERVE… For a wealth of quick, practical advice, access Section or Committee listserves (members-only, online discussion groups found on www.nysba.org) which focus on specific, substantive areas of law. With NYSBA Sections and Committees you can NETWORK… Meet judges and leading attorneys. Make valuable personal contacts and establish life long friendships. Attend con- tinuing legal education seminars where you can mix and mingle with some of the state’s finest legal minds. The value in NYSBA’s networking opportunities and collegiality is both irreplaceable and priceless. With NYSBA CLE you can SAVE TIME and SAVE 40%… Choose from our vast collection of New York continuing legal education courses while enjoying a members-only 40% discount. -

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 11/25/1969 Administrative Information

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 11/25/1969 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: November 25, 1969 Location: New York, New York Length: 46 pages Biographical Note Burns was Mayor of Binghamton, NY (1958-1966); chairman of the New York State Democratic Party (1965-1973); delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1968); and a Robert Kennedy campaign worker (1968). In this interview, he discusses the Robert F. Kennedy’s (RFK) decision to run for president in 1968, and the presidential campaign in New York State; RFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and Johnson’s decision not to run for reelection in 1968; negotiations with the Eugene J. McCarthy campaign over electoral delegates, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

RFK#3, 2/25/1970 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#3, 2/25/1970 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: February 25, 1970 Location: New York, New York Length: 30 pages Biographical Note Burns was Mayor of Binghamton, NY (1958-1966); chairman of the New York State Democratic Party (1965-1973); delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1968); and a Robert Kennedy campaign worker (1968). In this interview, he discusses Lyndon Baines Johnson’s hostility towards Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) and RFK’s associates; and Robert F. Kennedy’s involvement in the 1965 New York City mayoral race, the 1966 New York gubernatorial race, and the 1967 New York constitutional convention, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Reform in New York: the Budget, the Legislature and the Governance Process

REFORM IN NEW YORK: THE BUDGET, THE LEGISLATURE AND THE GOVERNANCE PROCESS A Background Paper Prepared For The Citizens Budget Commission Conference On “Fixing New York State’s Fiscal Practices” November 13-14, 2003 by Gerald Benjamin Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, SUNY New Paltz Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Albany Triad 6 A Professional Legislature – Members and Resources 8 Legislative Majorities and Leadership Power 17 Partisanship and Persistent Divided Party Control of the Legislature 23 Action Forcing Mechanisms 29 Budgeting and an Accountable Legislature: The Need for Constitutional Change 33 Introduction New York once prided itself as being a leader in governance among the states. Now mediocrity is the norm. One 50 state study is particularly revealing. In 2001 Governing Magazine, in collaboration with the Maxwell School of Syracuse University, graded the states in five key areas of government performance – Fiscal Management, Capital Management, Human Resources, Managing for Results, and Information Technology. New York got a "C+" average, and no grade higher than a "B." Those who prefer to think of the glass as half full might be encouraged by the improvement over the state's "C-" average reported two years earlier.1 But New York's improved Governing GPA (Grade Point Average) was helped by a higher grade in Fiscal Management. Knowing this, it would be understandable if those attentive to New York's fiscal practices and condition conclude that the state's movement from C- to C+ was evidence not of progress, but of grade inflation. The focal points of criticism of New York's fiscal practices are numerous, and have been regularly advanced by the Citizens Budget Commission and others. -

The Man Who Saved New York

The Man Who Saved New York 333621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd3621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd i 55/25/10/25/10 99:16:05:16:05 AMAM 333621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd3621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd iiii 55/25/10/25/10 99:16:06:16:06 AMAM The Man Who Saved New York Hugh Carey and the Great Fiscal Crisis of 1975 Seymour P. Lachman and Robert Polner excelsioree editions State University of New York Press Albany, New York 333621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd3621_SP_LAC_FM_00i-viii.indd iiiiii 55/25/10/25/10 99:16:06:16:06 AMAM Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2010 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press Production by Ryan Morris Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lachman, Seymour. The man who saved New York : Hugh Carey and the great fi scal crisis of 1975 / Seymour P. Lachmann and Robert Polner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-3453-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Finance, Public—New York (State)—New York.