The Greek Chorus Reinterpreted in Repo! the Genetic Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] 6iThe Adaptation of Literature to the Musical Stage: The Best of the Golden Age” b y Lee Ann Bratten M. Phil, by Research University of Glasgow Department of English Literature Supervisor: Mr. AE Yearling Ju ly 1997 ProQuest Number: 10646793 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uesL ProQuest 10646793 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

Scenes from Opera and Musical Theatre

LEON WILSON CLARK OPERA SERIES SHEPHERD SCHOOL OPERA presents an evening of SCENES FROM OPERA AND MUSICAL THEATRE Debra Dickinson, stage director Thomas Jaber, musical director and pianist January 30 and 31, February 1 and 2, 1998 7:30 p.m. Wortham Opera Theatre RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM DER FREISCHOTZ Music by Carl Maria von Weber; libretto by Johann Friedrich Act II, scene 1: Schelm, halt' fest// Kommt ein schlanker Bursch gegangen. Agatha: Leslie Heal Annie: Laura D 'Angelo CANDIDE Music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by John Latouche, Dorothy Parker, Stephen Sondheim, Richard Wilbur OHappyWe Candide: Matthew Pittman Cunegonde: Sibel Demirmen \. THE THREEPENNY OPERA Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Bertolt Brecht The Jealousy Duet Lucy Brown: Aidan Soder Polly Peachum: Kristina Driskill MacHeath: Adam Feriend DON GIOVANNI Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte Act I, scene 3: Laci darem la mano/Ah! fuggi ii traditor! Don Giovanni: Christopher Holloway Zerlina: Elizabeth Holloway Donna Elvira: Michelle Herbert STREET SCENE Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Elmer Rice Act/I Duet Rose: Adrienne Starr Sam: Matthew Pittman MY FAIR LADY Music by Frederick Loewe; lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner On the Street Where You Live/Show Me Freddy Eynsford Hill: David Ray Eliza Doolittle: Dawn Bennett LA BOHEME Music by Giacomo Puccini; libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Act/II Mimi: Kristin Nelson Marcello: Matthew George Rodolfo: Creighton Rumph Musetta: Adrienne Starr Directed by Elizabeth Holloway INTERMISSION LE NOZZE DI FIGARO -

South-Pacific-Script.Pdf

RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN'S SOUTH PACIFIC First Perfol'mance at the 1vlajestic Theatre, New York, A pril 7th, 1949 First Performance in London, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, November 1st, 1951 THE CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) NGANA JEROME HENRY ENSIGN NELLIE FORBUSH EMILE de BECQUE BLOODY MARY BLOODY MARY'S ASSISTANT ABNER STEWPOT LUTHER BILLIS PROFESSOR LT. JOSEPH CABLE, U.S.M.C. CAPT. GEORGE BRACKETT, U.S.N. COMMDR. WILLIAM HARBISON, U.S.N. YEOMAN HERBERT QUALE SGT. KENNETH JOHNSON SEABEE RICHARD WEST SEABEE MORTON WISE SEAMAN TOM O'BRIEN RADIO OPERATOR, BOB McCAFFREY MARINE CPL. HAMILTON STEEVES STAFF-SGT. THOMAS HASSINGER PTE. VICTOR JEROME PTE. SVEN LARSEN SGT. JACK WATERS LT. GENEVIEVE MARSHALL ENSIGN LISA MANELLI ENSIGN CONNIE WALEWSKA ENSIGN JANET McGREGOR ENSIGN BESSIE NOONAN ENSIGN PAMELA WHITMORE ENSIGN RITA ADAMS ENSIGN SUE YAEGER ENSIGN BETTY PITT ENSIGN CORA MacRAE ENSIGN DINAH MURPHY LIAT MARCEL (Henry's Assistant) LT. BUZZ ADAMS Islanders, Sailors, Marines, Officers The action of the play takes place on two islands in the South Pacific durin~ the recent war. There is a week's lapse of time between the two Acts. " SCENE I SOUTH PACIFIC ACT I To op~n.o House Tabs down. No.1 Tabs closed. Blackout Cloth down. Ring 1st Bar Bell, and ring orchestra in five minutes before rise. B~ll Ring 2nd Bar three minutes before rise. HENRY. A Ring 3rd Bar Bell and MUSICAL DIRECTOR to go down om minute before rise. NGANA. N Cue (A) Verbal: At start of overt14re, Music No.1: House Lights check to half. -

Street Scene

U of T Opera presents Kurt Weill’s Street Scene Artwork: Fred Perruzza November 22, 23 & 24, 2018 at 7:30 pm November 25, 2018 at 2:30 pm MacMillan Theatre, 80 Queen’s Park Made possible in part by a generous gift from Marina Yoshida. This performance is funded in part by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land. Street Scene Based on Street Scene by Elmer Rice Music by Kurt Weill Lyrics by Langston Hughes Conductor: Sandra Horst Director: Michael Patrick Albano Set and Lighting Design: Fred Perruzza Costume Design: Lisa Magill Choreography: Anna Theodosakis* Stage Manager: Susan Monis Brett* +Peter McGillivray’s performance is made possible by the estate of Morton Greenberg. *By permission of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc. promotes and perpetuates the legacies of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya by encouraging an appreciation of Weill’s music through support of performances, recordings, and scholarship, and by fostering an understanding of Weill’s and Lenya’s lives and work within diverse cultural contexts. It administers the Weill-Lenya Research Center, a Grant and Collaborative Performance Initiative Program, the Lotte Lenya Competition, the Kurt Weill/Julius Rudel Conducting Fellowship, the Kurt Weill Prize for scholarship in music theater; sponsors and media. -

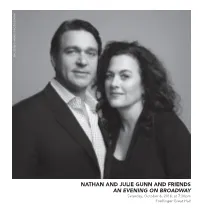

Nathan and Julie Gunn and Friends an Evening On

PHOTO BY SHARKEY PHOTOGRAPHY SHARKEY BY PHOTO NATHAN AND JULIE GUNN AND FRIENDS AN EVENING ON BROADWAY Saturday, October 6, 2018, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM NATHAN AND JULIE GUNN AND FRIENDS AN EVENING ON BROADWAY FEATURING PRODUCTION CREDITS Molly Abrams Sarah Wigley, dramatic coordinator Lara Semetko-Brooks Elliot Emadian, choreography Colleen Bruton Michael Williams, lighting Elliot Emadian Alec LaBau, audio Olivia Gronenthal Madelyn Gunn, production assistant Ryan Bryce Johnson Adeline Snagel, stage manager Nole Jones Savanna Rung, assistant stage manager Gabrielle LaBare J.W. Morrissette Logan Piker Andrew Turner Rachel Weinfeld ORCHESTRA Zachary Osinski, flute Emma Olson, oboe J. David Harris, clarinet Robert Brooks, saxophone Ronald Romm, trumpet Robert Sears, trumpet Michael Beltran, trombone Trevor Thompson, violin Amanda Ramey, violin Jacqueline Scavetta, viola Jordan Gunn, cello Lawrence Gray, bass Mary Duplantier, harp Ricardo Flores, percussion Julie Jordan Gunn, piano 2 Kurt Weill, music Street Scene (1946) Langston Hughes, lyrics Ice Cream Sextet Elmer Rice, book Ryan Bryce Johnson, Molly Abrams, Nole Jones, Gabrielle LaBare, Elliot Emadian, Andrew Turner Wouldn’t You Like to Be on Broadway? Lara Semetko-Brooks, Nathan Gunn What Good Would the Moon Be? Lara Semetko-Brooks, J.W. Morrissette Moon Faced, Starry Eyed Logan Piker, Elliot Emadian Frank Loesser, music and lyrics Guys and Dolls (1950) Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows, book Fugue for Tin Horns Nathan Gunn, Andrew Turner, Nole Jones Adelaide’s Lament Colleen Bruton Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat Nole Jones, Andrew Turner, Ryan Bryce Johnson, Elliot Emadian, Logan Piker Richard Rodgers, music Carousel (1945) Oscar Hammerstein II, book and lyrics Bench Scene Rachel Weinfeld, Nathan Gunn Carrie/Mr. -

Script Olivia Senior.Pdf

Olivia! Senior Script by Malcolm Sircom Ideal Cast Size 60 Speaking Roles 35 Minimum Cast Size 40 Duration (minutes) 120 2/120916/30 ISBN: 978 1 84237 095 7 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B77 5BY 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com No part of this publication may be transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, manuscript, typesetting, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. It is an infringement of the copyright to give any public performance or reading of this show either in its entirety or in the form of excerpts, whether the audience is charged an admission or not, without the prior consent of the copyright owners. Dramatic musical works do not fall under the licence of the Performing Rights Society. Permission to perform this show from the publisher ‘MUSICLINE PUBLICATIONS’ is always required. An application form, for permission to perform, is supplied at the back of the script for this purpose. To perform this show without permission is strictly prohibited. It is a direct contravention of copyright legislation and deprives the writers of their livelihood. Anyone intending to perform this show should, in their own interests, make application to the publisher for consent, prior to starting rehearsals. All Rights Strictly Reserved. Olivia Senior – Script 1 CONTENTS Cast List .............................................................................................................................. -

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre

Developmental Cross Training Repertoire for Musical Theatre Women The repertoire suggestions below target specific developmental goals. It is important to keep in mind however that the distinguishing characteristic of musical theatre singing is the variability of tonal resonance within any given song. A predominantly soprano song might suddenly launch into a belt moment. A chest dominant ballad may release into a tender soprano. Story always pre-empts musical choices. “Just You Wait” from My Fair Lady is part of the soprano canon but we would be disappointed if Eliza could not tell Henry Higgins what she really felt. In order to make things easier for beginning students, it’s a good idea to find repertoire with targeted range and consistent quality as students develop skill in coordinating registration. Soprano Mix—Beginner, Teens to Young Adult Examples of songs to help young sopranos begin to feel functionally confident and enthusiastic about characters and repertoire. Integrating the middle soprano is a priority and it is wise to start there. My Ship Lady in the Dark Weill Far from the Home I Love Fiddler on the Roof Bock/ Harnick Ten Minutes Ago Cinderella Rodgers/Hammerstein Mr. Snow Carousel Rodgers/Hammerstein Happiness is a Thing Called Joe Cabin in the Sky Arlen/Harburg One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Dream with Me Peter Pan Bernstein Just Imagine Good News! DeSylva/Brown So Far Allegro Rodgers/Hammerstein A Very Special Day Me and Juliet Rodgers/Hammerstein How Lovely to be a Woman Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams One Boy Bye Bye Birdie Strouse/Adams Lovely Funny Thing. -

NE Top Honors POSTING LIST

North East Regional Top Honors Showcase Video Event School Selection Showcase 1 Showcase 1 1 Senior NE Duet Acting ALLEN D NEASE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Chicken Bones For The Teenage Soup - Alan Haehnel Showcase 1 2 Senior NE Small Group Musical ASTRONAUT HIGH SCHOOL On the Verge- Women On the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown V Showcase 1 3 Senior NE Solo BARTRAM TRAIL HIGH SCHOOL Calm - Ordinary Days Showcase 1 4 Senior NE Publicity Direction Boca Raton Christian School Tuck Everlasting Showcase 1 5 Senior NE Duet Acting CELEBRATION HIGH SCHOOL Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead - Tom Stoppard Showcase 1 6 Senior NE Monologue CHARLOTTE HIGH SCHOOL Thoroughly Modern Millie by Richard Morris and Street Scene by Elmer Rice Showcase 1 7 Senior NEMonologue DOUGLAS ANDERSON SCHOOL OF THE ARTS Reasons to be Pretty - Neil Labute Happenstance - Craig Rospisil Showcase 1 8 Senior NE Solo EPISCOPAL SCHOOL OF JACKSONVILLE(HS) When It All Falls Down - Chaplin Showcase 1 9 Senior NE Duet Acting FLAGLER-PALM COAST HIGH SCHOOL Wait Wait Bo Bait - Lindsay Price Showcase 1 10 Senior NE Duet Acting HAGERTY HIGH SCHOOL Stop Kiss - Diana Son Showcase 1 11 Senior NE Costume Design LAKE HOWELL HIGH SCHOOL Grease the Musical Showcase 1 12 Senior NE Duet Musical LAKE HOWELL HIGH SCHOOL I will Never Leave you-Sideshow Showcase 1 13 Senior One act LAKE MARY HIGH SCHOOL For Whom the Southern Belle Tolls- Christopher Durang Showcase 1 14 Senior NE Duet Acting LYMAN HIGH SCHOOL True West Showcase 1 15 Senior NE Make-up Design MANDARIN HIGH SCHOOL Alice in Wonderland -L S D SA V RC P Showcase 1 16 Senior NE Solo PALM BAY SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Im Alive - NEXT TO NORMAL Showcase 1 17 Senior NE Costume Construction RIDGEVIEW HIGH SCHOOL The Addams Family by Rick Elice and Marshall Brickman Showcase 1 18 Senior NE Solo ROCKLEDGE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Fly Fly Away - Catch Me If You Can Religious Showcase 1 19 Senior NE Duet Acting SEMINOLE HIGH SCHOOL Mr Luckys - Stephen Fife Showcase 1 20 Senior NE Ensemble Acting ST. -

Street Scene

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene A Study Guide prepared by VIRGINIA OPERA 1 Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of World Premiere 3 Cast of Characters 3 Musical numbers 4 Brief plot summary 5 Full plot synopsis with musical examples 5 Historical background 12 The creation of the opera 13 Relevance of social themes in 21st century America 15 Notable features of musical style 16 Discussion questions 19 3 STREET SCENE AN AMERICAN OPERA Music by KURT WEILL Book by ELMER RICE, adapted from his play of the same name Lyrics by LANGSTON HUGHES Premiere First performance on January 9, 1947 at the Adelphi Theater in New York City Setting The action takes place outside a tenement house in New York City on an evening in June 1946. -

LOVE LIFE Your Personal Guide to the Production

NEW YORK CITY CENTER EDUCATION MARCH 2020 BEHIND THE CURTAIN: Wiseman Art by Ben ENCORES! LOVE LIFE Your personal guide to the production. TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTEXT 2 A Note from Jack Viertel, Encores! Artistic Director 3 Meet the Creative Team 4 Meet the Cast 5 An Interview with Costume Designer Tracy Christensen 7 Love Life in the 21st Century by Rob Berman and Victoria Clark RESOURCES & ACTIVITIES 10 Before the Show 11 Intermission Activity 13 After the Show 14 Glossary 15 Up Next for City Center Education CONTEXT Selecting shows for Encores! has always been a wonderfully A NOTE FROM enjoyable but informal process, in which Rob Berman, our Music Director and I toss around ideas and titles until we feel like we’ve achieved as perfect a mix as possible: three shows that we are as eager to see as we are to produce, and three JACK that are nothing alike. This year was different only in that we were joined by Lear deBessonet, who will begin her tenure as my successor next season. That only made it more fun, and VIERTEL, we proceeded as if it were any other season. ENCORES! Although we never considered the season a “themed” one— it turned out to have a theme: worlds in transition. And I ARTISTIC suppose my world, and maybe the world of Encores! itself are DIRECTOR about to change too—so it seems appropriate. Love Life is a case in point. Produced in 1948, it is Alan Jay Lerner and Kurt Weill’s only collaboration (they had tremendous success in other collaborations, including My Fair Lady and The Threepenny Opera). -

A Performer's Guide to the American Theater Songs of Kurt Weill

A Performer's Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Morales, Robin Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:09:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194115 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATER SONGS OF KURT WEILL (1900-1950) by Robin Lee Morales ________________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As member of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read document prepared by Robin Lee Morales entitled A Performer’s Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Faye L. Robinson_________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Edmund V. Grayson Hirst__________________ Date: May 5, 2008 John T. Brobeck _________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

SANIBEL MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM NOTES Opera Theater of Connecticut Andrew Lloyd Webber Superstar of Song and Stage Kate A

SANIBEL MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM NOTES Opera Theater of Connecticut Andrew Lloyd Webber Superstar of Song and Stage Kate A. Ford, General Director ~ Alan Mann, Artistic Director Eric Trudel, Music Director and Piano, Carly Callahan, Sarah Callinan, Matt Morgan, Charles Widmer, Mark Womack Tuesday, March 24, 2020 PROGRAM ASPECTS OF LOVE book and music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics by Don Black and Charles Hart Love Changes Everything………………………………………………………... Ensemble THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics by Charles Hart, book by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Richard Stilgoe Think of Me………………………………………………………………..Sarah Callinan All I Ask of You……………………………………………..Sarah Callinan, Matt Morgan The Music of the Night……………………………………………………Mark Womack The Phantom of the Opera………………………………Sarah Callinan, Mark Womack JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics by Tim Rice Pilate’s Dream……………………………………………………………..Mark Womack Herod’s Song………………………………………………………………...Matt Morgan I Don’t Know How to Love Hi……………………………………………Carly Callahan My Mind is Clearer Now………………………………………………..Charles Widmer Gethsemane………………………………………………………………….Matt Morgan Superstar………………………………………………………………………...Ensemble ~INTERMISSION~ EVITA music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics and book by Tim Rice The Lady’s Got Potential…………Charles Widmer, Sarah Callinan, Carly Callahan I’d Be Surprisingly Good for You……………………….Carly Callahan, Mark Womack High Flying, Adore……………………………………………………...Charles Widmer You Must Love Me………………………………………………………..Carly Callahan Another Suitcase…………………………………………………………..Sarah Callinan Don’t Cry for Me Argentina……………………………………………...Carly Callahan CATS Music and book by Andrew Lloyd Webber, lyrics by Andrew Lloyd Webber, based on the 1939 poetry collection Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T. S. Eliot. Memory……………………………………………………………………...Sarah Callinan WHISTLE DOWN THE WIND music by Andrew Lloyd Webber, book by Andrew Lloyd Webber, Patricia Knop, and Gale Edwards, lyrics by Jim Steinman.