20Th and 21St Century Practices in the Music of Björk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sally Anne Morgan Thread

BULLY SUGAREGG CD / LP / CS SP 1363 RELEASE DATE: AUGUST 21ST, 2020 TRACKLISTING: 1. Add It On 2. Every Tradition 3. Where to Start 4. Prism 5. You 6. Let You 7. Like Fire 8. Stuck in Your Head 9. Come Down 10. Not Ashamed 11. Hours and Hours 12. What I Wanted GENRE: Alternative Rock SUGAREGG roars from the speakers and jumpstarts both heart and mind. Like My Bloody Valentine after three double espressos, opener “Add It On” zooms heavenward within seconds, epitomizing band leader Alicia Bognanno’s newfound clarity of purpose, while the bass-driven melodies and propulsive beats of “Where to Start” and CD Packaging: Digipack “Let You” are the musical equivalents of the sun piercing through a LP Packaging: Single-pocket jacket with perpetually cloudy sky. custom dust sleeve Includes mp3 coupon A very old saying goes that no one saves us but ourselves. Recognizing NON-RETURNABLE and breaking free from the patterns impeding our forward progress can be transformative. Indeed, the third Bully album, SUGAREGG, may not ever have come to fruition had Bognanno not navigated every kind of upheaval imaginable and completely overhauled her working process along the way. The artist admits that finding the proper treatment for bipolar 2 disorder radically altered her mindset, freeing her from a cycle of paranoia and insecurity about her work. “Being able to finally navigate CS Packaging: Three-panel LP Packaging: Single-pocket jacket with that opened the door for me to write about it,” she says, pointing to J-card in clear case. custom dust sleeve the sweet, swirly “Like Fire” and slower, more contemplative songs NON-RETURNABLE LOSER EDITION blue w/white smoke such as “Prism” and “Come Down” as having been born of this new vinyl - Includes mp3 coupon NON-RETURNABLE headspace. -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

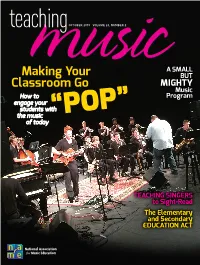

Making Your Classroom Go

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Pierrot Lunaire Translation

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Pierrot Lunaire, Op.21 (1912) Poems in French by Albert Giraud (1860–1929) German text by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905) English translation of the French by Brian Cohen Mondestrunken Ivresse de Lune Moondrunk Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder, A flots verts de la Lune coule, Flows nightly from the Moon in torrents, Und eine Springflut überschwemmt Et submerge comme une houle And as the tide overflows Den stillen Horizont. Les horizons silencieux. The quiet distant land. Gelüste schauerlich und süß, De doux conseils pernicieux In sweet and terrible words Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten! Dans le philtre yagent en foule: This potent liquor floods: Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder. A flots verts de la Lune coule. Flows from the moon in raw torrents. Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt, Le Poète religieux The poet, ecstatic, Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke, De l'étrange absinthe se soûle, Reeling from this strange drink, Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt Aspirant, - jusqu'à ce qu'il roule, Lifts up his entranced, Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürit er Le geste fou, la tête aux cieux,— Head to the sky, and drains,— Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt. Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux! The wine we drink with our eyes! Columbine A Colombine Colombine Des Mondlichts bleiche Bluten, Les fleurs -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Matmos “Ultimate Care Ii” / Klara Lewis

Press release Berlin, 19. April 2016 CTM Festival & Berghain present MATMOS “ULTIMATE CARE II” / KLARA LEWIS 1 JUNE 2016 | BERGHAIN | DOORS 20:00 | START 21:00 ADDRESS: AM WRIEZENER BAHNHOF, 10243 BERLIN TICKETS: 20 € advance: EVENTBRITE More Information: Berghain.de | ctm-festival.de | Facebook event page Presented by HHV Magazin A division of DISK / CTM – Baurhenn, Rohlf, Schuurbiers GbR • Veteranenstraße 21, 10119 Berlin, Germany | PAGE Tax Number 34/496/01492 • International VAT Number DE813561158 \* Bank Account: Berliner Sparkasse • BLZ: 10050000 • KTO: 636 24 508 • IBAN: De42 1005 0000 0063 6245 08 • BIC: BE LA DE BE MERGE The idea to make an album entirely out of the sounds of a washing machine came to Matmos’ Martin Schmidt as he drummed his fingers on the Whirlpool Ultimate Care II in his home studio, lost in abstracted contemplation of its cyclical rhythms. What began as a lark turned into a profound investigation into the creative process itself. “It started with just the sound of the washing machine itself” says Drew Daniel, the Baltimore-based duo’s other half. “We made a recording of its full cycle, but we were really disappointed.” Matmos then began experimenting, so that the album’s arc became “more and more elaborately involved in the question of: How do we turn this into an instrument?” Many experimental laundry sessions later, and with guest appearances by Dan Deacon, Max Eilbacher and Sam Haberman (Horse Lords), Jason Willett (Half Japanese) and Duncan Moore (Needle Gun), the album was released by Thrill Jockey in February 2016. Presented as one continuous track, the album is 38 minutes long, exactly the length of one wash cycle, and is titled Ultimate Care II, after its star. -

Minimalism Post-Modernism Is a Term That Refers to Events After the So

Post-Modernism - Minimalism Post-Modernism is a term that refers to events after the so-called Modern period. The term suggests that we are now using what we learned in the “modern” period, but mixing it with ideas from the more distant past. A major movement within Post-Modernism is Minimalism Minimalism mixes some Eastern philosophical principles involving chant and meditation with simple tonal materials. Basic definition of Minimalism: sustained or repetitive use of simple (often tonal) materials. The movement began with LaMonte Young (b.1935); he used simple textures and consonant materials; often called trance music. Terry Riley (b.1935) is credited with first minimalist work In C (1964). The piece has repeated high C’s on piano maintaining simple pulse. Score has 53 short motives to be played by a group any size; players play all 53 figures, repeating as many times and as frequently as desired. Performance ends when all players are done with all 53 figures. Because figures change in content, there is subtle but constantly shifting texture all the time. Steve Reich (b. 1936) prefers to call his music “Structural” not minimal. His music is influenced by his study of African drumming. Some of his early works use phasing, where a tape loop is set up: the tape records first sounds made by performer; then plays them back while performer continues to play. More layers are added, and gradually live sounds get ahead of play-back. Effect can be hypnotic: trance-like. Violin Phase (1967) is example. In Mid-70’s Reich expanded his viewpoint and his ensemble: Music for 18 Musicians is a little like In C, but there is much more variation in patterns. -

Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown: Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire Mike Fabio Introduction In September of 1912, a 37-year-old Arnold Schoenberg sat in a Berlin concert hall awaiting the premier of his 21st opus, Pierrot Lunaire. A frail man, as rash in his temperament as he was docile when listening to his music, Schoenberg watched as the lights dimmed and a fully costumed Pierrot took to the stage, a spotlight illuminating him against a semitransparent black screen through which a small instrumental ensemble could be seen. But as Pierrot began singing, the audience quickly grew uneasy, noting that Pierrot was in fact a woman singing in the most awkward of styles against a backdrop of pointillist atonal brilliance. Certainly this was not Beethoven. In a review of the concert, music critic James Huneker wrote: The very ecstasy of the hideous!…Schoenberg is…the cruelest of all composers, for he mingles with his music sharp daggers at white heat, with which he pares away tiny slices of his victim’s flesh. Anon he twists the knife in the fresh wound and you receive another thrill…. There is no melodic or harmonic line, only a series of points, dots, dashes or phrases that sob and scream, despair, explode, exalt and blaspheme.1 Schoenberg was no stranger to criticism of this nature. He had grown increasingly contemptuous of critics, many of whom dismissed his music outright, even in his early years. When Schoenberg entered his atonal period after 1908, the criticism became far more outrageous, and audiences were noted to have rioted and left the theater in the middle of pieces.