Court of Appeals of the State Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King County Official Local Voters' Pamphlet

August 2, 2016 Primary and Special Election King County Official Local Voters’ Pamphlet Your ballot will arrive by July 18 206-296-VOTE (8683) | kingcounty.gov/elections Reading the local From the voters’ pamphlet Director Why are there measures in the local voters’ pamphlet that are not on my ballot? Dear Friends. The measures on your ballot refl ect the districts in which you are registered to This is a big year for King County Elections. To vote. The local voters’ pamphlet may cover start, we are on track to hit 10 million ballots multiple districts and include measures counted without a single discrepancy this fall. outside of your districts. We expect to process over 1 million ballots this November alone. What is the order of candidates in the local voters’ pamphlet? I’m eager to continue our track record of transparency and accuracy – especially in light of Candidates in the local voters’ pamphlet this year’s Presidential Election – and I am also appear in the order they will appear on the excited about several projects that will mean ballot. transformative change for elections. For this Primary Election you will now have access to Are candidate statements fact checked 29 permanent ballot drop boxes that are open before they are published? 24-hours-a-day. November will see that number No. King County Elections is not responsible increase to 43 ballot drop boxes, meaning that for the content or accuracy of the 91.5% of King County residents will live within 3 statements, and we print them exactly as miles of a drop-off location. -

Enforcement of Music, Movie Licensing Is Stepped up Unbelted Bus Drivers

June 15, 2010 Enforcement of music, movie licensing is stepped up NEW YORK CITY — The minding them if they play record- movies and television programs primer on music and movie from the license holder. three organizations that license bar, ed music or show movies or televi- for artists, writers, and studios. licensing. “By playing pre-recorded music elevator and motorcoach operators sion programs for their onboard The notices have been so wide- The association pointed out (and movies) to the passengers on to play recorded music, videos, customers they must pay a licens- spread the United Motorcoach As- that music and movies are like all your coach, you are essentially pro- DVDs, CDs and tapes for their cus- ing fee. sociation has been inundated with property: they belong to the people viding a public performance of that tomers have stepped up enforce- The notifications to coach op- calls from members with questions who created and own them. To le- (material),” UMA points out. ment of federal copyright laws. erators have come from ASCAP, about the licensing. gally play recorded music or show It doesn’t matter if a passenger Motorcoach operators across BMI and Motorcoach Movies UMA issued an electronic flyer movies to the public, operators brings the music or movie onboard; the U.S. have been sent notices re- which handle licensing of music, to members, providing them with a must, by law, obtain permission CONTINUED ON PAGE 10 c NW operators embrace rival to Sen. Murray SEATTLE — Motorcoach op- erators here may have found a can- didate they can support in their ef- fort to defeat their No. -

Voters.Indd Clallam

2 FOR THE ELECTION O F NOVEMBER 4, 2008 VOTE ! 2008 VOTER GUIDE PENINSULA DAILY NEWS S T A T E O F W A S H I N G T O N Introduction: Election ends Nov. 4 at 8 p.m. THIS SPECIAL SECTION tionnaires were limited to 75 ballot in the official return enve- house. of the Peninsula Daily News, also words per question and were lope, and don’t forget to sign the ■ Nov. 3: Last day for write-in available at no charge at the edited for length, grammar and envelope. candidates to file a Declaration county courthouse, libraries and spelling. Fill in the square next to your of Candidacy for the Nov. 4 elec- other public places across Clal- Races in which there is only choice. And make no identifying tion. lam County, provides voters with one candidate are not profiled in marks on your ballot. ■ Nov. 25: Deadline for information about the Nov. 4 this section. Neither are write-in Putting more than one ballot County Canvassing Board to cer- general election. candidates. in a return envelope, signifying tify the general election returns. It profiles the candidates for In Clallam County, all voting your choice with an X or check ■ Nov. 26: Last day for county countywide and local races in is done by mail. There is no Elec- mark (✔) instead of completely to mail abstract of general elec- which there are more than two tion Day precinct polling. inking in the square, or placing tion returns to state. candidates, and also discusses Mail-in ballots were sent to an identifying mark on a ballot ■ Dec. -

Edition 15F Introduction to the 2008 Primary Voters’ Pamphlet

STATE OF WASHINGTON Look inside for more about the Top 2 Primary VOTERS’’PAMPHLET VOTERS PAMPHLET August 19, 2008 Primary Washington’s New Top 2 Primary Washington has a new primary. You do not have Each candidate for partisan offi ce may state a political to pick a party. In each race, you may vote for any party that he or she prefers. A candidate’s preference one of the candidates listed. Th e two candidates does not imply that the candidate is nominated or who receive the most votes in the August Primary endorsed by the party, or that the party approves will advance to the November General Election. of or associates with that candidate. Look inside for more about the Top 2 Primary. PUBLISHED BY THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE AND KING COUNTY ELECTIONS EDITION 15F Introduction to the 2008 Primary Voters’ Pamphlet It’s your choice … it’s your voice. Dear King County voter: Congratulations on exercising your privilege and responsibility A lot has changed since the last presidential election in 2004. to take part in Washington’s elections − never more important Since then, King County Elections has worked tirelessly to than in this watershed 2008 election year. Our new Top 2 implement more than 300 reforms and recommendations Primary on August 19 will give you maximum choice, allowing resulting from outside audits, election experts, and the you the independence and freedom to “vote for the person, innovative work of elections staff. With these changes and not the party.” 19 successful elections behind us, King County is ready and energized for the August 19 primary. -

No Guessing Allowed: Washington Rejects Proportionate Deduction in Election Contests

RAVA - FINAL EDIT6.DOC 4/26/2006 7:15:17 PM NO GUESSING ALLOWED: WASHINGTON REJECTS PROPORTIONATE DEDUCTION IN ELECTION CONTESTS William C. Rava & Rebecca S. Engrav* Eight months after the votes had been cast, and after two recounts1 and no fewer than nine lawsuits,2 the 2004 Washington * Mr. Rava is a partner and Ms. Engrav is an associate at Perkins Coie LLP in Seattle. A team of lawyers, including Mr. Rava, Ms. Engrav, and others, represented the Washington State Democratic Central Committee in all of the litigation regarding the 2004 general election, including the election contest described in this essay. 1 Republican Dino Rossi won the initial count by 261 votes over Democrat Christine Gregoire, triggering an automatic machine recount pursuant to section 29A.64.021(1) of the Revised Code of Washington Annotated. See In re Election Contest of Coday, 2006 WL 572831, at *1 (Wash. Mar. 9, 2006). After the machine recount narrowed Rossi’s lead to only forty-two votes, the Washington State Democratic Central Committee requested a second manual recount of all votes cast in the governor’s race pursuant to section 29A.64.011 of the Revised Code of Washington Annotated. See Coday, 2006 WL 572831, at *1; News Release, Wash. Sec’y of State, Reed to Issue Recount Order Monday (Dec. 3, 2004), http://www.secstate.wa.gov/office/osos_news.aspx?i=1hOl46bKPVHBqzrKlJtzCg%3D%3D. Gregoire won the manual recount by 129 votes. See Coday, 2006 WL 572831, at *2. For more information about the two recounts and the history of recounts in Washington, see Washington Secretary of State, Washington State 2004 General Elections, http://vote.wa.gov/general (last visited Jan. -

2016 POLITICAL DONATIONS Made by WEYERHAEUSER POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (WPAC)

2016 POLITICAL DONATIONS made by WEYERHAEUSER POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (WPAC) ALABAMA U.S. Senate Sen. Richard Shelby $2,500 U.S. House Rep. Robert Aderholt $5,000 Rep. Bradley Byrne $1,500 Rep. Elect Gary Palmer $1,000 Rep. Martha Roby $2,000 Rep. Terri Sewell $3,500 ARKANSAS U.S. Senate Sen. John Boozman $2,000 Sen. Tom Cotton $2,000 U.S. House Rep. Elect Bruce Westerman $4,500 FLORIDA U.S. House Rep. Vern Buchanan $2,500 Rep. Ted Yoho $1,000 GEORGIA U.S. Senate Sen. Johnny Isakson $3,000 U.S. House Rep. Rick Allen $1,500 Rep. Sanford Bishop $2,500 Rep. Elect Buddy Carter $2,500 Rep. Tom Graves $2,000 Rep. Tom Price $2,500 Rep. Austin Scott $1,500 IDAHO U.S. Senate Sen. Mike Crapo $2,500 LOUISIANA U.S. Senate Sen. Bill Cassidy $1,500 U.S. House Rep. Ralph Abraham $5,000 Rep. Charles Boustany $5,000 Rep. Garret Graves $1,000 Rep. John Kennedy $2,500 Rep. Stephen Scalise $3,000 MAINE U.S. Senate Sen. Susan Collins $1,500 Sen. Angus King $2,500 U.S. House Rep. Bruce Poliquin $2,500 MICHIGAN U.S. Senate Sen. Gary Peters $1,500 Sen. Debbie Stabenow $2,000 MINNESOTA U.S. Senate Sen. Amy Klobuchar $2,000 U.S. House Rep. Rick Nolan $1,000 Rep. Erik Paulsen $1,000 Rep. Collin Peterson $1,500 MISSISSIPPI U.S. Senate Sen. Roger Wicker $4,000 U.S. House Rep. Gregg Harper $4,000 Rep. Trent Kelly $3,000 Rep. -

Notice of Elections

Sherril Huff, Director Elections Division NOTICE OF ELECTIONS NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that on Tuesday, August 19, 2008, in King County, State of Washington, at the polling places listed separately, there will be held a Primary Election for the purpose of electing candidates for the offices listed below and Special Elections for submitting to the voters for their approval or rejection the ballot measures as listed. The names and addresses of candidates and the offices for which they have been nominated are: Top 2: A new voting process for Washington’s August 19 primary Cheryl Pflug Legislative District No. 36 Legislative District No. 47 Special elections held in conjunction with the (Prefers Republican Party) Partisan Offices Partisan Offices August 19, 2008, primary election 23705 230th Pl SE You do not have to pick a party. State Representative Position No. 1 State Representative Position No. 1 Maple Valley, WA 98038 John Burbank Leslie Kae Hamada KING COUNTY In each race, you may vote for any candidate listed. Representative Position No. 1 (Prefers Democratic Party) (Prefers Democratic Party) INITIATIVE 26 AND COUNCIL-PROPOSED Jon Viebrock 6755 Sycamore Ave NW 28026 189th Ave SE ALTERNATIVE The two candidates who receive the most votes in the August (Prefers Democratic Party) Seattle, WA 98117 Covington, WA 98042 The following initiative proposed ordinance (Initiative PO Box 2015 primary will advance to the November General Election. Leslie Bloss Geoff Simpson 26) and council proposed alternative ordinance Issaquah, WA 98027 (Prefers G O P Party) (Prefers Democratic Party) (Council-Proposed Alternative) concern the election Each candidate for partisan office may state a political party that Jay Rodne PO Box 50135 16624 SE 254th Pl of nonpartisan county officials and the nonpartisan he or she prefers. -

2018 Senate Ratings 2018 S

This issue brought to you by North Dakota Senate: Heitkamp Hoping for Another Home Run Campaign MAY 4, 2018 VOLUME 2, NO. 9 By Leah Askarinam The map of competitive Senate races has opened up to some unexpected places. One year ago, it seemed unlikely that we’d be 2018 Senate Ratings discussing2018 whether Democrats Senate could win a RatingsSenate seat in Tennessee or Toss-Up Texas, let alone that the GOP would lose a seat in Alabama. But North Dakota has been on the map sinceToss-Up the day after the November 2012 Donnelly (D-Ind.) McCaskill (D-Mo.) election,Donnelly when (D-Ind.) Heidi Heitkamp squeakedManchin out a(D-W.Va.) victory to keep the seat in Heitkamp (D-N.D.) Nelson (D-Fla.) Democratic hands. Heitkamp (D-N.D.) McCaskill (D-Mo.) Heller (R-Nev.) AZ Open (Flake, R) Just a couple years before Heitkamp ran for Senate, North Dakota’s Manchin (D-W.Va.) congressionalHeller (R-Nev.)# delegation was entirely Democratic. Two of those seats fell Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican toTilt Republicans Democratic before Heitkamp tookTilt office—one Republican was ousted by a GOP challenger, and another retired. Republicans were confident that they’d Baldwin (D-Wis.) Baldwin (D-Wis.) take over the third seat in a state where President Barack Obama was Nelson (D-Fla.) Tester (D-Mont.) unpopular. But Heitkamp ran a near-perfect campaign and Democrats Lean Democratic Lean Republican heldTester the (D-Mont.) seat by nine-tenths of a percentage point. Brown (D-Ohio) TN Open (Corker, R) LeanThis Democratictime around, a couple thingsLean remain Republican the same. -

2010 Primary Election – Sample Ballot Thurston County, WA

2010 Primary Election – Sample Ballot Thurston County, WA Primary Election, Sample Ballot Thurston County, Washington August 17, 2010 This sample ballot contains all candidates and measures certified to appear on the August 17, 2010 Primary Election ballot. Be sure to follow all instructions on your regular ballot. Ballots will begin arriving on July 29, 2010. If you require a replacement ballot, please contact our office at (360) 786-5408. READ: Each candidate for partisan office may state a political party that he or she prefers. A candidate’s preference does not imply that the candidate is nominated or endorsed by the party, or that the party approves of or associates with that candidate. 2010 Primary Election – Sample Ballot Thurston County, WA Federal Partisan Offices U. S. Senator Six Year Term Vote for One Norma D. Gruber (Prefers Republican Party) Mohammad H. Said (Prefers Centrist Party) Goodspaceguy (Prefers Democratic Party) Mike The Mover (Prefers Democratic Party) Paul Akers (Prefers Republican Party) Mike Latimer (Prefers Republican Party) James (Skip) Mercer (States No Party Preference) Clint Didier (Prefers Republican Party) Schalk Leonard (States No Party Preference) Patty Murray (Prefers Democratic Party) Bob Burr (Prefers Democratic Party) William Edward Chovil (Prefers Republican Party) Dino Rossi (Prefers Republican Party) Charles Allen (Prefers Democratic Party) Will Baker (Prefers Reform Party) _______________ Write in U. S. Representative, District No. 3 Two Year Term Vote for One Jaime Herrera (Prefers Republican Party) Denny Heck (Prefers Democratic Party) David W. Hedrick (Prefers Republican Party) David B. Castillo (Prefers Republican Party) Cheryl Crist (Prefers Democratic Party) Norma Jean Stevens (Prefers Independent Party) _______________ Write in U. -

Murray Still up Two Over Rossi

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 19, 2010 INTERVIEWS: DEAN DEBNAM 888-621-6988 / 919-880-4888 (serious media inquiries only please, other questions can be directed to Tom Jensen) QUESTIONS ABOUT THE POLL: TOM JENSEN 919-744-6312 Murray Still Up Two Over Rossi Raleigh, N.C. – In PPP’s first look at the Washington Senate race since employing a likely voter screen, the picture looks almost the same as with registered voters before the August primary: incumbent Democrat Patty Murray at 49% and hanging onto a narrow lead over Republican victor and perennial candidate Dino Rossi. Murray tops Rossi, 49-47. In a poll taken July 27th to August 1st, she was up, 49-46. While Murray has halved her previous 12-point deficit with independents, unaffiliateds now comprise a smaller portion of the electorate, at 29%, than in August (35%), with Republicans making up significantly more, at 34% versus 29%. Democrats are up to 37% from 36%. Both candidates have over 90% of their respective party bases behind them, though Murray is taking slightly more Republicans than Rossi is Democrats. The projected electorate reports voting for Barack Obama over John McCain by only 7 points, 10 less than his actual margin of victory in 2008. The previous poll reflected a 10-point Obama lead. Were turnout like 2008’s, Murray would have a 53-43 edge. 14% of respondents claim to have already cast ballots in this vote-by-mail state. Murray is cushioning herself against a possible late Rossi surge, with early voters favoring her, 52-47. Based entirely on a ten-point GOP edge with independents, Washington voters are split just slightly in favor of Republican control of the Senate, 47-46 over Democrats, a sentiment on which Rossi is not capitalizing. -

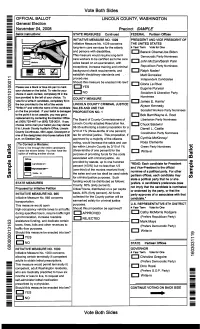

2008 General Sample

Vote Both Sides OFFICIAL BALLOT LINCOLN COUNTY, WASHINGTON General Election November 04,2008 Precinct SAMPLE Ballot Instructions: STATE MEASURES Continued FEDERAL Partisan Offices INITIATIVE MEASLIRE NO. 1029 PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT OF Initiative Measure No. 1029 concerns THE UNITED STATES long-term care services for the elderly 4 Year Term Vote for One and persons with disabilities. 1Barack ObamalJoe Biden This measure would require long-term Democratic Party Nominees care workers to be certified as home care John McCainlSarah Palin aides based on an examination, with 1 exceptions; increase training and criminal Republican Party Nominees background check requirements; and Ralph Naderl establish disciplinary standards and , Matt Gonzalez procedures. Independent Candidates Should this measure be enacted into law? 0Gloria La Rival Please use a black or blue Ink pen to mark a YES Eugene Puryear your choices on the ballot. To vote for your choice In each contest, completely fill in the 0NO Socialism & Liberation Party Nominees box provided to the left of your chol~e.TO COUNTY MEASURE vote for a write-in candidate, completely fill in . 1James E. Harris1 the box provided to the left of the words LINCOLN COUNTY CRIMINAL JUSTICE Alyson Kennedy "Write-inwand write the name of the candidate SALES AND USE TAX Socialist Workers Party Nominees on the line provided. If your ballot is damaged p~opo~l~lo~NO. 1 to the point It Is not useable, you may get a Bob BarrMlayne A. Root replacement by contacting the Election Office ~h~ ~~~~dof county ~~~~i~~i~~~~~of Libertarian Party Nominees at: (509) 725-4971 Or (800) 7253031* If you Lincoln County adopted Resolution No. -

United States

United States US Senator Education: Warren received a Navy scholarship to and graduated from Oregon State University in Chemical Engineering. Before college he was a national guards- man and after graduation served eighteen years as a commissioned naval officer and received training in nuclear - biological - chemical defense and deep sea diving. Occupation: Warren commercially fished for salmon in Washington and Alaska for forty plus years and currently is working as a casual longshoreman at the Tacoma and Seattle ports. Professional Qualifications: Warren’s military service, mental and physical strengths, life experiences, hard work. Plus willingness to accept difficult tasks qualifies him to meet the challenges of this office. Personal Information: Warren is a single man of excellent health with an active Warren E. Hanson mind, spirit and body. He is the father of three healthy daughters with two excellent Democratic sons-in-laws, three grandchildren and one additional young lady, a mother of four, PMB 444 who is like a fourth daughter. 4320 196th St SW Community Involvement: Warren has served in many church capacities, as a Red Cross Board Member and is a frequent blood donor. Lynnwood, WA 98036 Personal Views: Warren will work forcefully to secure our boarders, to drastically (425) 418-2736 reduce illegals, to be more selective in legal entries and to solve the many problems that interfere with a good life for all citizen Americans. Education: Occupation: Professional Qualifications: Personal Information: Community Involvement: Personal Views: Washington state is a great place to live and raise a family. We must preserve and build on the things that make us strong.