Mitchell's Musings April – June 2018 for Employment Policy Research Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understandingamericastudy

UnderStandingAmericaStudy UAS 154: 2018 CALIFORNIA PRE-MIDTERM ELECTION POLL Survey author(s): Jill Darling, Robert Shrum Fielded September 17, 2018 - October 14, 2018 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Topics . .3 1.2 Experiments . .3 1.3 Citation . .3 2 Survey Response And Data 4 2.1 Sample selection and response rate . .4 2.2 Timings . .4 2.3 Sample & Weighting . .5 3 Standard Variables 6 4 Background Demographics 9 5 Missing Data Conventions 13 6 Routing Syntax 14 7 Survey with Routing 15 poll............................................. 15 propositions . 25 voting . 30 election . 31 Closing . 33 1 INTRODUCTION This UAS panel survey, titled ”UAS 154: 2018 California Pre-Midterm Election poll” focuses on issues of relevance to the 2018 midterm election in California, including races for Gov- ernor, US Senate, Prop 6 (Gas tax), and Prop 10 (Rent Control). This survey is no longer in the field. Respondents were paid $4 to complete the survey. Note: A summary of all UAS midterm polls and their documentation is provided on the UAS 2018 Midterm Election Data Page (https://uasdata.usc.edu/page/UAS+2018+Midterm+Election). 1.1 Topics This survey contains questions (among others) on the following topics: Politics. A complete survey topic categorization for the UAS can be found here. 1.2 Experiments This survey includes experiment(s) of the following type(s): Auxiliary Randomization. Please refer to explanatory comments in the Routing section for detailed information. A complete survey experiment categorization for the UAS can be found here. 1.3 Citation Each publication, press release or other document that cites results from this survey must include an acknowledgment of UAS as the data source and a disclaimer such as, ‘The project described in this paper relies on data from survey(s) administered by the Under- standing America Study, which is maintained by the Center for Economic and Social Re- search (CESR) at the University of Southern California. -

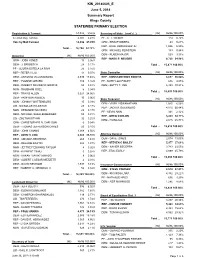

Of 477 Total Registered Voters Precinct Registration Precinct Ballots

Total Registration and Turnout LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR ATTORNEY GENERAL Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 Total Registered Voters 388,298 ELENI KOUNALAKIS 54,068 34.22% XAVIER BECERRA 92,393 60.98% Precinct Registration 388,298 JEFF BLEICH 31,295 19.81% DAVE JONES 23,515 15.52% Precinct Ballots Cast 0 0.00% ED HERNANDEZ 26,108 16.52% STEVEN C BAILEY 23,147 15.28% Vote Center Ballots Cast 12,566 3.24% COLE HARRIS 13,411 8.49% ERIC EARLY 12,466 8.23% Vote by Mail Ballots Cast 159,510 41.08% DAVID FENNELL 10,085 6.38% INSURANCE COMMISSIONER Total Ballots Cast 172,076 44.32% LYDIA ORTEGA 7,867 4.98% GAYLE MCLAUGHLIN 6,409 4.06% GOVERNOR Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 DAVID R. HERNANDEZ 3,858 2.44% TIM FERREIRA 2,462 1.56% Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 CAMERON GHARABIKLOU 1,645 1.04% RICARDO LARA 63,550 41.96% DANNY THOMAS 794 0.50% STEVE POIZNER 55,910 36.91% MARJAN S. FARIBA (W) 0 0.00% GAVIN NEWSOM 92,488 55.02% ASIF MAHMOOD 25,571 16.88% JOHN H. COX 23,378 13.91% SECRETARY OF STATE NATHALIE HRIZI 6,434 4.25% ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA 17,406 10.36% MEMBER, STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION 2ND DISTRICT JOHN CHIANG 11,890 7.07% Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 TRAVIS ALLEN 8,539 5.08% DELAINE EASTIN 5,871 3.49% Complete Precincts: 477 of 477 AMANDA RENTERIA 2,219 1.32% ALEX PADILLA 102,525 66.21% ROBERT C. -

Statewide Primary Election Summary Report 6.26.18

KIN_20180605_E June 5, 2018 Summary Report Kings County STATEWIDE PRIMARY ELECTION Registration & Turnout 51,342 Voters Secretary of State (cont'd...) (86) 86/86 100.00% Election Day Turnout 2,707 5.27% PF - C. T. WEBER 114 0.72% Vote by Mail Turnout 14,092 27.45% GRN - ERIK RYDBERG 43 0.27% REP - RAUL RODRIGUEZ JR 1,046 6.59% Total ... 16,799 32.72% GRN - MICHAEL FEINSTEIN 133 0.84% DEM - RUBEN MAJOR 529 3.33% Governor (86) 86/86 100.00% REP - MARK P. MEUSER 8,726 54.98% GRN - JOSH JONES 10 0.06% DEM - J. BRIBIESCA 28 0.17% Total ... 15,871 100.00% PF - GLORIA ESTELA LA RIVA 25 0.15% REP - PETER Y LIU 11 0.07% State Controller (86) 86/86 100.00% DEM - ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA 2,836 17.40% REP - KONSTANTINOS RODITIS 8,637 55.04% REP - YVONNE GIRARD 189 1.16% PF - MARY LOU FINLEY 636 4.05% DEM - ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS 55 0.34% DEM - BETTY T. YEE 6,420 40.91% NON - SHUBHAM GOEL 6 0.04% Total ... 15,693 100.00% REP - TRAVIS ALLEN 3,921 24.06% DEM - AKINYEMI AGBEDE 10 0.06% State Treasurer (86) 86/86 100.00% NON - JOHNNY WATTENBURG 15 0.09% DEM - VIVEK VISWANATHAN 1,025 6.56% LIB - NICKOLAS WILDSTAR 28 0.17% REP - JACK M. GUERRERO 4,815 30.84% NON - DESMOND SILVEIRA 28 0.17% PF - KEVIN AKIN 331 2.12% DEM - MICHAEL SHELLENBERGER 50 0.31% REP - GREG CONLON 5,429 34.77% LIB - ZOLTAN ISTVAN 32 0.20% DEM - FIONA MA 4,015 25.71% GRN - CHRISTOPHER N. -

Special Municipal Election June 6, 2018

RESOLUTION NO. ___ A RESOLUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SANTA BARBARA CERTIFYING THE ELECTION RESULTS OF THE OFFICIAL CANVASS FOR THE SPECIAL MUNICIPAL ELECTION HELD IN THE CITY ON JUNE 6, 2018 WHEREAS, on Tuesday, June 6, 2018, a Special Municipal Election was held in the City of Santa Barbara to elect a City Councilmember to represent District 3 for the remainder of the term expiring at the end of 2019; WHEREAS, by its Resolution No. 18-010, adopted on February 6, 2018, the City Council requested the Board of Supervisors of the County of Santa Barbara to consolidate the Special Municipal Election with the Statewide Direct Primary Election; WHEREAS, the Special Municipal Election was consolidated with the Statewide Direct Primary Election on June 6, 2018; and WHEREAS, the County Clerk, Recorder and Assessor & Registrar of Voters of the County of Santa Barbara has completed a canvass of election results and submitted to the City the Certification of Election Results of the Official Canvass. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SANTA BARBARA AS FOLLOWS: SECTION 1. The City Council does hereby certify the Election Results of the Official Canvass of the Special Municipal Election consolidated with the Statewide Primary Election held in the City of Santa Barbara on Tuesday, June 6, 2018, as shown on the attached Certification of Election Results of the Official Canvass, dated June 25, 2018, and marked as "Exhibit A." SECTION 2. The City Clerk shall certify to the passage and adoption of this Resolution and enter it into the book of original Resolutions. -

PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians and Their Government. March 2018

PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY MARCH 2018 Californians & Their Government Mark Baldassare Dean Bonner Alyssa Dykman Lunna Lopes CONTENTS Press Release 3 2018 California Election 6 State and National Issues 11 Regional Map 21 Methodology 22 Questionnaire and Results 24 Supported with funding from the James Irvine Foundation and the PPIC Donor Circle The PPIC Statewide Survey provides a voice for the public and likely voters— informing policymakers, encouraging discussion, and raising awareness on critical issues of the day. © 2018 Public Policy Institute of California The Public Policy Institute of California is dedicated to informing and improving public policy in California through independent, objective, nonpartisan research. PPIC is a public charity. It does not take or support positions on any ballot measures or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or of the staff, officers, advisory councils, or board of directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY MARCH 2018 CONTACT Susan Gluss 415-291-4412 Serina Correa 415-291-4417 News Release EMBARGOED: Do not publish or broadcast until 9:00 p.m. PDT on Wednesday, March 21, 2018 Para ver este comunicado de prensa en español, por favor visite nuestra página de internet: www.ppic.org/press-release/ PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY: CALIFORNIANS AND THEIR GOVERNMENT Newsom Solidifies Lead, Cox Gains Ground, Feinstein Maintains Edge over de León MOST LIKELY VOTERS FAVOR STATE BONDS FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING, WATER PROJECTS SAN FRANCISCO, March 21, 2018—Democrat Gavin Newsom has surged ahead of Antonio Villaraigosa in the state’s gubernatorial race, and Republican John Cox has made headway among the state’s likely voters. -

Contra Costa County Ordinance Code

TRANSPORTATION, WATER & INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE December 11, 2017 9:00 A.M. 651 Pine Street, Room 101, Martinez Supervisor Diane Burgis, Chair Supervisor Karen Mitchoff, Vice Chair Agenda Items may be taken out of order based on the business of the day and preference Items: of the Committee 1. Introductions 2. Public comment on any item under the jurisdiction of the Committee and not on this agenda (speakers may be limited to three minutes). 3. Administrative Items, if applicable. (John Cunningham, Department of Conservation and Development) pg. 4 of 228 4. REVIEW record of meeting for October 9, 2017, Transportation, Water and Infrastructure Committee. This record was prepared pursuant to the Better Government Ordinance 95-6, Article 25-205 (d) of the Contra Costa County Ordinance Code. Any handouts or printed copies of testimony distributed at the meeting will be attached to this meeting record. (John Cunningham, Department of Conservation and Development) pg. 5 of 228 5. REVIEW record of special meeting for November 7, 2017, Transportation, Water and Infrastructure Committee. This record was prepared pursuant to the Better Government Ordinance 95-6, Article 25-205 (d) of the Contra Costa County Ordinance Code. Any handouts or printed copies of testimony distributed at the meeting will be attached to this meeting record. (John Cunningham, Department of Conservation and Development) pg. 9 of 228 6. RECEIVE the report on Mobility Matters Ride’s 4 Veteran’s Program, and DIRECT staff as appropriate. (John Cunningham, Department of Conservation and Development) pg. 12 of 228 7. RECEIVE report on Sustainable Groundwater Management in Contra Costa County. -

LCF Latino California Gubernatorial Survey – January 17, 2018

LCF Latino California Gubernatorial Survey – January 17, 2018 Results Among Latino Registered Voters Statewide I'm going to read you the names of several people. After I read each one, please tell me if you have a very favorable view, somewhat favorable view, somewhat unfavorable view, or very unfavorable view of them. If you haven't heard of them or are unfamiliar with them, just tell me that. [RANDOMIZE] {Favorable} {Unfavorable} Total Total Very Some Some Very No opin Fav Unfav 1. Gavin Newsom 15 19 10 8 48 34 18 +16 2. Antonio Villaraigosa 26 35 11 8 19 61 19 +42 3. John Chiang 7 25 10 4 55 32 14 +18 4. Delaine Eastin 6 17 8 6 64 23 14 +9 5. John Cox 3 11 5 4 75 14 9 +5 6. Travis Allen 5 14 6 3 73 19 9 +10 7. Donald Trump 13 9 8 64 5 22 72 -50 8. Jerry Brown 31 35 12 14 8 66 26 +40 9. Barack Obama 58 24 6 10 2 83 16 +67 10. On the whole, what are the most important issues facing the [Hispanic/Latino] community in California that you think the next Governor of California should address? [RESPONDENT MAY SELECT ONE OR TWO – RECORD ORDER OF MENTION IF TWO] Welcoming immigrants and protecting their rights ................. 30 Creating jobs………………………………………………………………………….22 Improving public schools .......................................................... 20 Improving the economy ............................................................ 17 Improving access to health care ............................................... 14 Making college more affordable .............................................. 9 Investing in and expanding housing affordability… .................. 7 Addressing Race relations / discrimination .............................. 6 Decreasing government spending / Lower taxes .................... -

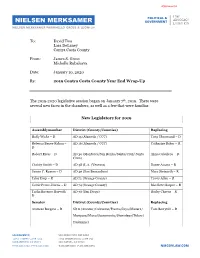

2019 State Legislative Program Year-End Report

Attachment A To: David Twa Lara DeLaney Contra Costa County From: James S. Gross Michelle Rubalcava Date: January 10, 2020 Re: 2019 Contra Costa County Year End Wrap-Up The 2019-2020 legislative session began on January 7th, 2019. There were several new faces in the chambers, as well as a few that were familiar. New Legislators for 2019 Assemblymember District (County/Counties) Replacing Buffy Wicks – D AD 15 (Alameda / CCC) Tony Thurmond – D Rebecca Bauer-Kahan – AD 16 (Alameda / CCC) Catharine Baker – R D Robert Rivas – D AD 30 (Monterey/San Benito/Santa/Cruz/ Santa Anna Caballero – D Clara) Christy Smith – D AD 38 (L.A. /Ventura) Dante Acosta – R James C. Ramos – D AD 40 (San Bernardino) Marc Steinorth – R Tyler Diep – R AD 72 (Orange County) Travis Allen – R Cottie Petrie-Norris – D AD 74 (Orange County) Matthew Harper – R Tasha Boerner Horvath – AD 76 (San Diego) Rocky Chavez – R D Senator District (County/Counties) Replacing Andreas Borgeas – R SD 8 (Amador/Calaveras/Fresno/Inyo/Madera/ Tom Berryhill – R Mariposa/Mono/Sacramento/Stanislaus/Tulare/ Tuolumne) Anna Caballero – D SD 12 (Fresno/Madera/Merced/Monterey/San Anthony Cannella – Benito/Stanislaus) R Melissa Hurtado – D SD 14 (Fresno/Kern/Kings/Tulare) Andy Vidak – R Shannon Grove – R SD 16 (Kern/Tulare/San Bernardino) Jean Fuller – R Susan Rubio – D SD 22 (L.A.) Ed Hernandez – D Maria Elena Durazno – D SD 24 (L.A.) Kevin de León – D Bob J. Archuleta – D SD 32 (L.A./Orange) Vanessa Delgado – D Tom Umberg – D SD 34 (L.A./Orange) Janet Nguyen – R VACANT (Effective 11/1) SD 28 (Riverside) Jeff Stone - R Brian Jones – R SD 38 (San Diego) Joel Anderson – R Governor Newsom’s first budget proposal…FY 2019-20 On January 10, 2019, Californians got their first substantive glimpses of Governor Newsom’s priorities. -

Newsom and Cox Now the Clear Leaders in California's Top Two

Jack Citrin Center for Public Opinion Research Institute of Governmental Studies 124-126 Moses Hall University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 Tel: 510-642-6835 Email: [email protected] Release #2018-08 For Publication: Thursday, May 31, 2018 Newsom and Cox now the clear leaders in California’s top two primary election for governor. By Mark DiCamillo, Director, Berkeley IGS Poll (o) 510-642-6835 (c) 415-602-5594 Less than a week before California holds its primary election, a new Berkeley IGS Poll finds Democrat Gavin Newsom and Republican John Cox outdistancing the large field of twenty- seven candidates running in the gubernatorial primary. The latest survey finds Newsom holding a commanding lead, with 33% of the preferences of likely voters and Cox in second, at 20%. Democrat Antonio Villaraigosa and Republican Travis Allen trail, receiving 13% and 12% of the vote, respectively. The two candidates with the most votes in the primary, regardless of party, square off against one another in the November general election. The preferences of likely voters in the governor’s race are highly partisan. The poll finds Democratic candidates receiving an aggregate 89% of the preferences of likely Democrats voters, with Newsom receiving the dominant share (50%). Similarly, Republican candidates are receiving an aggregate 86% of the GOP vote, with 53% going to Cox. The views that partisans have of the two poll leaders are also quite positive, with 68% of Democrats holding a favorable opinion of Newsom and 64% of Republicans voicing high regard for Cox. The poll finds Newsom and Cox also holding large leads among voters who say they have already voted in the primary. -

Californians and Their Government, December 2017

PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY DECEMBER 2017 Californians & Their Government Mark Baldassare Dean Bonner Lunna Lopes CONTENTS Press Release 3 2018 California Election 6 State and National Issues 13 Regional Map 20 Methodology 21 Questionnaire and Results 23 Supported with funding from the James Irvine Foundation, the California Endowment, and the PPIC Donor Circle The PPIC Statewide Survey provides a voice for the public and likely voters— informing policymakers, encouraging discussion, and raising awareness on critical issues of the day. © 2017 Public Policy Institute of California The Public Policy Institute of California is dedicated to informing and improving public policy in California through independent, objective, nonpartisan research. PPIC is a public charity. It does not take or support positions on any ballot measures or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or of the staff, officers, advisory councils, or board of directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY DECEMBER 2017 CONTACT Linda Strean 415-291-4412 Serina Correa 415-291-4417 News Release EMBARGOED: Do not publish or broadcast until 9:00 p.m. PST on Thursday, November 30, 2017. Para ver este comunicado de prensa en español, por favor visite nuestra página de internet: www.ppic.org/press-release PPIC STATEWIDE SURVEY: CALIFORNIANS AND THEIR GOVERNMENT Newsom, Villaraigosa Lead Governor’s Race—Many Are Undecided FEINSTEIN HAS TWO-TO-ONE EDGE OVER DE LEÓN IN US SENATE RACE SAN FRANCISCO, November 30, 2017—Six months before the gubernatorial primary, Democrats Gavin Newsom and Antonio Villaraigosa are leading in the top-two primary race among California’s likely voters. -

Certified List of Candidates Contact List

Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 5, 2018 Official Contact List of Candidates 3/29/2018 Page 1 of 147 GOVERNOR AKINYEMI AGBEDE Democratic 6775 SANTA MONICA BLVD #4-254 LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 (559) 230-7913 (Business) WEBSITE: www.thenextgovernorofcalifornia2018.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Mathematician J. BRIBIESCA Democratic 3298 GOVERNOR DR #22917 SAN DIEGO, CA 92122 WEBSITE: www.juanbribiesca.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Retired Medical Doctor THOMAS JEFFERSON CARES Democratic 3739 BALBOA ST #1179 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94121 (310) 421-8683 (Business) WEBSITE: www.tomcares.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Blockchain Startup CEO JOHN CHIANG Democratic 16633 VENTURA BLVD #1008 ENCINO, CA 91436 California State Treasurer DELAINE EASTIN Democratic 5940 COLLEGE AVE STE F OAKLAND, CA 94618 (510) 214-3302 (Business) WEBSITE: www.delaineforgovernor.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Educator/Youth Advocate ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS Democratic 743 OAKLAND AVE APT 11 OAKLAND, CA 94611 (510) 367-2828 (Business) WEBSITE: www.facebook.com/griff4gov E-MAIL: [email protected] Entrepreneur/Economist/Father * Incumbent Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 5, 2018 Official Contact List of Candidates 3/29/2018 Page 2 of 147 GOVERNOR ALBERT CAESAR MEZZETTI Democratic 30200 GARDEN RD MANTECA, CA 95337 (209) 825-6566 (Business) E-MAIL: [email protected] Retired Educator GAVIN NEWSOM Democratic 268 BUSH ST #4600 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94104 (415) 326-4164 (Business) WEBSITE: www.gavinnewsom.com E-MAIL: [email protected] Lieutenant -

Certified List of Candidates-Shortlist

Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 5, 2018 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/29/2018 Page 1 of 87 GOVERNOR AKINYEMI AGBEDE Democratic Mathematician J. BRIBIESCA Democratic Retired Medical Doctor THOMAS JEFFERSON CARES Democratic Blockchain Startup CEO JOHN CHIANG Democratic California State Treasurer DELAINE EASTIN Democratic Educator/Youth Advocate ROBERT DAVIDSON GRIFFIS Democratic Entrepreneur/Economist/Father ALBERT CAESAR MEZZETTI Democratic Retired Educator GAVIN NEWSOM Democratic Lieutenant Governor/Businessman AMANDA RENTERIA Democratic COO, Justice Department MICHAEL SHELLENBERGER Democratic Environmental Organization Executive KLEMENT TINAJ Democratic CEO/Educator/Artist * Incumbent Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 5, 2018 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/29/2018 Page 2 of 87 GOVERNOR ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA Democratic Public Policy Advisor TRAVIS ALLEN Republican California Assemblyman/Businessman JOHN H. COX Republican Businessman/Taxpayer Advocate YVONNE GIRARD Republican Judicial Assistant PETER Y LIU Republican No Ballot Designation ROBERT C. NEWMAN, II Republican Research Clinical Psychologist CHRISTOPHER N. CARLSON Green Puppeteer/Musician JOSH JONES Green Author ZOLTAN ISTVAN Libertarian Entrepreneur/Transhumanist Lecturer NICKOLAS WILDSTAR Libertarian Recording Artist GLORIA ESTELA LA RIVA Peace and Freedom Graphic Artist * Incumbent Statewide Direct Primary Election - June 5, 2018 Official Certified List of Candidates 3/29/2018 Page 3 of 87 GOVERNOR SHUBHAM GOEL No Party Preference Virtual Reality