Deux `` Traductions '' Anglaises De Richard Coeur-De-Lion (1784)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

![Chapter 3 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3751/chapter-3-pdf-963751.webp)

Chapter 3 [PDF]

Chapter 3 Was There a Crisis of Opera?: The Kroll Opera's First Season, 1927-28 Beethoven's "Fidelio" inaugurated the Kroll Opera's first season on November 19, 1927. This was an appropriate choice for an institution which claimed to represent a new version of German culture - the product of Bildung in a republican context. This chapter will discuss the reception of this production in the context of the 1927-28 season. While most accounts of the Kroll Opera point to outraged reactions to the production's unusual aesthetics, I will argue that the problems the opera faced during its first season had less to do with aesthetics than with repertory choice. In the case of "Fidelio" itself, other factors were responsible for the controversy over the production, which was a deliberately pessimistic reading of the opera. I will go on to discuss the notion of a "crisis of opera", a prominent issue in the musical press during the mid-1920s. The Kroll had been created in order to renew German opera, but was the state of opera unhealthy in the first place? I argue that the "crisis" discussion was more optimistic than it has generally been portrayed by scholars. The amount of attention generated by the Kroll is evidence that opera was flourishing in Weimar Germany, and indeed was a crucial ingredient of civic culture, highly important to the project of reviving the ideals of the Bildungsbürgertum. 83 84 "Fidelio" in the Context of Republican Culture Why was "Fidelio" a representative German opera, particularly for the republic? This work has not always been viewed as political in nature. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

ROSSINI’S THE ITALIAN GIRL IN ALGIERS AN IN-DEPTH GUIDE © 2007 Michal Daniel Written by Stu Lewis ROSSINI’S WOMAN OF VALOR “Cruda sorte” – cruel fate! These are the first words we hear from Isabella, the title character of Rossini’s L’Italiana in Algeri (The Italian Girl in Algiers). Captured by pirates, looking – in vain, she believes – for her lover, soon to be forced to become part of an Arab potentate’s harem, she certainly is someone who has the right to sing the blues, or at least the nineteenth- century Italian equivalent. And so she does – for twenty-six bars – which is all the time that a Rossini heroine has for self-pity. As she moves to the up-tempo cabaletta, she reminds us that no man, however powerful, could possibly control an intelligent woman. And so it goes with the Rossini mezzo. Like Rosina in The Barber of Seville, who acts docile as long as she has her way and turns into a viper when she doesn’t, Isabella clearly has the inner resources to come out on top. Critic Andreas Richter calls her a “female Don Giovanni” – albeit, without the latter’s amorality. As the Don had the three principal female characters in the opera gravitating toward him, Isabella wins the affection of three men – one of each voice type – manipulating two of them mercilessly. (Another similarity: like Mozart’s opera, l’Italiana is labelled a “dramma giocosa” – a jolly drama). L’Italiana is a rescue opera, but, as Beethoven was to do years later in Fidelio, Rossini and Anelli turn the rescue theme on its head by making the woman the rescuer. -

Holover-Opera-Part-1.Pdf

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Item 69 Catalogue 82 OPERA SCORES from the Collection of Jerome Holover (1943-2013) Part 1: A-L 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA Telephone 516-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to insure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. v Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Fine Items & Collections Purchased v Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

From Prop to Producer

From Prop to Producer: The Appropriation of Radio Technology in Opera during the Weimar Republic Katy Vaughan Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2020 2 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 3 Katy Vaughan From Prop to Producer: The Appropriation of Radio Technology in Opera during the Weimar Republic Abstract This thesis explores the appropriation of radio technology in opera composed during the Weimar Republic. It identifies a gap in current research where opera and radio have often been examined separately in the fields of musicology and media history. This research adopts a case study approach and combines the disciplines of musicology and media history, in order to create a narrative of the use of radio as a compositional tool in Weimar opera. The journey begins with radio as a prop on stage in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny speilt auf (1927) and ends with the radio as a producer in Walter Goehr’s radio opera Malpopita (1931). Max Brand's Maschinist Hopkins (1929) provides an interlude between these two works, where its analysis serves to pinpoint compositional techniques used in radio opera. The opera case studies reflect the changing attitudes towards technology and media in Weimar musicology, as shown in the journal, Musikblätter des Anbruch (1919-1937). -

German Writers on German Opera, 1798–1830

! "# $ % & % ' % !"# $!%$! &#' !' "(&(&()(( *+*,(-!*,(."(/0 ' "# ' '% $$(' $(#1$2/ 3((&/ 14(/ Propagating a National Genre: German Writers on German Opera, 1798–1830 A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2010 by Kevin Robert Burke BM Appalachian State University, 2002 MM University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Dr. Mary Sue Morrow ABSTRACT Standard histories of Western music have settled on the phrase “German Romantic opera” to characterize German operatic developments in the early part of the nineteenth century. A consideration of over 1500 opera reviews from close to thirty periodicals, however, paints a more complex picture. In addition to a fascination with the supernatural, composers were drawn to a variety of libretti, including Biblical and Classical topics, and considered the application of recitative and other conventions most historians have overlooked because of their un-German heritage. Despite the variety of approaches and conceptions of what a German opera might look like, writers from Vienna to Kassel shared a common aspiration to develop a true German opera. The new language of concert criticism found from specialized music journals like the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung to the entertainment inserts of feuilletons like the Zeitung für die elegante Welt made the operatic endeavor of the early nineteenth century a national one rather than a regional one as it was in the eighteenth century. ii Copyright 2010, Kevin Robert Burke iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to offer gratitude to all my colleagues, friends, and family who supported me with encouraging words, a listening ear, and moments of celebration at the end of each stage. -

Carolyn Kirk Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE VIENNESE VOGUE FOR OPÉRA-COMIQUE 1790-1819 : VOL 1. Carolyn Kirk A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7282 This item is protected by original copyright The Viennese vogue for opera—comique 1790-1819 submitted by Carolyn Kirk In fulfilment of the requirements for Ph.D. degree of the University of St. Andrews, November, 1983 ii ABSTRACT In the mid-eighteenth century, Vienna, like other European cities, began to manifest the influence of modern French culture; In 1752, a troupe of French players was appointed to the Austrian court to entertain the aristocracy. Four years later, links were forged • between the Parisian and Viennese stages via Favart who corresponded with Count Durazzo in Vienna and sent opera scores and suggestions about personnel. In 1765 problems with finance and leadership led to dismissal of Vienna's first French troupe but others performed there for shorter periods between .:1765 and 1780. Opera-comique was introduced to Vienna by French players. Occasional performances of opera-comique in German translation took place in Vienna during the 1770s. When, in 1778, the Nationalsingspiel was founded, French opera formed part of the repertoire because of a lack of good German works. A renewed interest in opèra-comique began in about 1790 when fear of revolutionary France and the reigns of Leopold and Franz led to a return of interest in Italian opera at the court theatres, and the virtual disappearance of opêra-comique from its repertoire. -

Romantic Undertones in Revolutionary France: the Case for Tarare As Spark for the Revolution

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2021 Romantic Undertones in Revolutionary France: The Case for Tarare as Spark For The Revolution Sean Robert Stephenson Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2021 SEAN ROBERT STEPHENSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School ROMANTIC UNDERTONES IN REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE: THE CASE FOR TARARE AS SPARK FOR THE REVOLUTION A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Sean Robert Stephenson College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Music Performance May 2021 This Dissertation by: Sean Robert Stephenson Entitled: Romantic Undertones in Revolutionary France: The Case for Tarare as Spark for the Revolution has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the Department of Music Accepted by the Doctoral Committee _______________________________________________________ Jonathan Bellman DMA, Research Advisor _______________________________________________________ Derek Chester DMA, Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Brian Luedloff MFA, Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Jacob Melish Ph.D, Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense March 30th, 2021 Accepted by the Graduate School _________________________________________________________ -

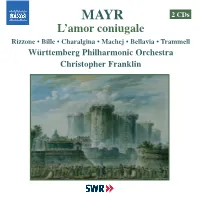

Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 12

660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 12 2 CDs Also available: MAYR L’amor coniugale Rizzone • Bille • Charalgina • Machej • Bellavia • Trammell Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Christopher Franklin 8.660203-04 8.660220-21 8.660198-99 12 660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 2 Simon MAYR (1763-1845) Also available: L’amor coniugale (1805) Farsa sentimentale in one act Libretto by Gaetano Rossi (1774-1855) after Jean Nicolas Bouilly Zeliska/Malvino . Cinzia Rizzone, Soprano Amorveno . Francescantonio Bille, Tenor Floreska . Tatjana Charalgina, Soprano Peters . Dariusz Machej, Bass Moroski . Giovanni Bellavia, Bass-baritone Ardelao . Bradley Trammell, Tenor Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Christopher Franklin 8.660037-38 Assistant: Marco Bellei Edition by Florian Bauer for performance at the ROSSINI IN WILDBAD festival, after the revised score of Arrigo Gazzaniga 8.660183-84 8.660198-99 211 8.660198-99 660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 10 Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Reutlingen CD 1 43:49 CD 2 39:08 The Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Reutlingen was established in 1 Sinfonia 7:42 1 Scena: Qual notte eterna (Amorveno) 5:35 1945, developing into one of the leading orchestras in South Germany. It has worked under the direction of, among others, Samuel Friedman, Salvador 2 Gira gira non ti stare attortigliar 2 Aria: Cara immagine adorata (Amorveno) 4:09 Mas Conde and Roberto Paternostro and, since September 2001, Norichika (Floreska, Peters) 4:29 Iimori, who led a highly successful concert tour to Japan in 2006. In addition 3 Animo... ma... cos’hai paura? (Peters, Zeliska) 1:33 to concert series in Reutlingen the orchestra broadcasts regularly with 3 Südwestrundfunk and appears in various cities of South Germany, with tours Sono qua (Zeliska, Peters, Floreska) 4:33 to Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Spain and The Netherlands, often with very 4 Romanza: Una moglie sventurata distinguished soloists. -

Gothic Opera in Britain and France: Genre, Nationalism, and Trans-Cultural Angst Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English Department 5-1-2004 Gothic Opera in Britain and France: Genre, Nationalism, and Trans-Cultural Angst Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected] Sarah Davies Cordova Marquette University Published version. Romanticism on the Net, Vol. 34-35 (May, 2004). Permalink. © 2004 University of Montreal. Used with permission. Gothic Opera in Britain and France: Genre, Nationalism, and Trans-Cultural Angst Diane Long Hoeveler Marquette University Sarah Davies Cordova Marquette University Abstract Rescue operas developed along two somewhat different lines: “tyrant” operas and “humanitarian” operas within the general category of “opera semiseria,” or “opéra comique.” The first type corresponds to the conservative British “loyalty gothic,” with its focus on the trials and tribulations of the aristocracy, while the second type draws upon the Sentimental “virtue in distress” or “woman in jeopardy” genre, with its focus on middle class characters or women as the captured or besieged. The first category emphasized political injustice or abstract questions of law and embodied the threat of tyranny in an evil man who imprisons unjustly a noble character. Etienne Méhul’s Euphrosine and H.-M. Berton’s Les rigueurs du cloître (both 1790) are typical examples of the genre. “Humanitarian” operas, on the other hand, do not depict a tyrant, but instead portray an individual—usually a woman or a worthy bourgeois—who sacrifices everything in order to correct an injustice or to obtain some person’s freedom. Dalayrac’s Raoul, Sire de Créqui (1789) or Bouilly’s and Cherubini’s Les deux journées (1800) are examples, along with Sedaine’s pre-1789 works. -

Melodramatic Voices: Understanding Music Drama

Melodramatic Voices: Understanding Music Drama Edited by Sarah Hibberd MELODRAMATIC VOICES: UNDERSTANDING MUSIC DRAMA ASHGATE INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES IN OPERA Series Editor Roberta Montemorra Marvin University of Iowa, USA Advisory Board Linda Hutcheon, University of Toronto, Canada David Levin, University of Chicago, USA Herbert Lindenberger, Emeritus Professor, Stanford University, USA Julian Rushton, Emeritus Professor, University of Leeds, UK The Ashgate Interdisciplinary Studies in Opera series provides a centralized and prominent forum for the presentation of cutting-edge scholarship that draws on numerous disciplinary approaches to a wide range of subjects associated with the creation, performance, and reception of opera (and related genres) in various historical and social contexts. There is great need for a broader approach to scholarship about opera. In recent years, the course of study has developed significantly, going beyond traditional musicological approaches to reflect new perspectives from literary criticism and comparative literature, cultural history, philosophy, art history, theatre history, gender studies, film studies, political science, philology, psycho-analysis, and medicine. The new brands of scholarship have allowed a more comprehensive interrogation of the complex nexus of means of artistic expression operative in opera, one that has meaningfully challenged prevalent historicist and formalist musical approaches. The Ashgate Interdisciplinary Studies in Opera series continues to move this important trend forward by including essay collections and monographs that reflect the ever- increasing interest in opera in non-musical contexts. Books in the series will be linked by their emphasis on the study of a single genre – opera – yet will be distinguished by their individualized and novel approaches by scholars from various disciplines/fields of inquiry. -

Opéra-Comique, Cultural Politics and Identity in Scandinavia 1760–1800

Scandinavian Journal of History ISSN: 0346-8755 (Print) 1502-7716 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/shis20 OPÉRA-COMIQUE, CULTURAL POLITICS AND IDENTITY IN SCANDINAVIA 1760–1800 Charlotta Wolff To cite this article: Charlotta Wolff (2018) OPÉRA-COMIQUE, CULTURAL POLITICS AND IDENTITY IN SCANDINAVIA 1760–1800, Scandinavian Journal of History, 43:3, 387-409, DOI: 10.1080/03468755.2018.1464631 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2018.1464631 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 15 May 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 175 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=shis20 Scandinavian Journal of History, 2018 Vol. 43, No. 3, 387–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2018.1464631 Charlotta Wolff OPÉRA-COMIQUE, CULTURAL POLITICS AND IDENTITY IN SCANDINAVIA 1760–1800 As a contribution to the history of public life and cultural practice, this article examines the political and social implications of the fondness for French comic opera in Scandinavia between 1760 and 1800. The urban elites’ interest in opéra-comique is examined as a part of the self-fashioning processes of mimetism and distinction, but also as a way to consolidate the community. Opéra-comique was promoted by the literary and diplomatic elites. It became important for the cultural politics of the Scandinavian monarchies as well as for intellectual milieus able to propose alternative models for life in society. The appropriation of opéra-comique by an expanding public transformed the nature of the supposedly aristocratic and cosmopolitan genre, which became an element in the defining of new bourgeois and patriotic identities.