Intractable Conflict, Adaptable Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DJ Playlist.Djp

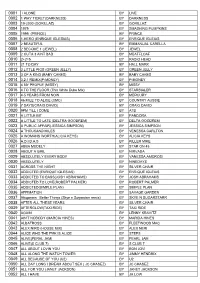

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Keyfinder V2 Dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014

KeyFinder v2 dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014 ARTIST TITLE KEY 10CC Dreadlock Holiday Gm 187 Lockdown Gunman (Natural Born Chillers Remix) Ebm 4hero Star Chasers (Masters At Work Main Mix) Am 50 Cent In Da Club C#m 808 State Pacifc State Ebm A Guy Called Gerald Voodoo Ray A A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? (Boilerhouse Mix) Em A Tribe Called Quest Find A Way Ebm A Tribe Called Quest Vivrant Thing (feat Violator) Bbm A-Skillz Drop The Funk Em Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? Dm AC-DC Back In Black Em AC-DC You Shook Me All Night Long G Acid District Keep On Searching G#m Adam F Aromatherapy (Edit) Am Adam F Circles (Album Edit) Dm Adam F Dirty Harry's Revenge (feat Beenie Man and Siamese) G#m Adam F Metropolis Fm Adam F Smash Sumthin (feat Redman) Cm Adam F Stand Clear (feat M.O.P.) (Origin Unknown Remix) F#m Adam F Where's My (feat Lil' Mo) Fm Adam K & Soha Question Gm Adamski Killer (feat Seal) Bbm Adana Twins Anymore (Manik Remix) Ebm Afrika Bambaataa Mind Control (The Danmass Instrumental) Ebm Agent Sumo Mayhem Fm Air Sexy Boy Dm Aktarv8r Afterwrath Am Aktarv8r Shinkirou A Alexis Raphael Kitchens & Bedrooms Fm Algol Callisto's Warm Oceans Am Alison Limerick Where Love Lives (Original 7" Radio Edit) Em Alix Perez Forsaken (feat Peven Everett and Spectrasoul) Cm Alphabet Pony Atoms Em Alphabet Pony Clones Am Alter Ego Rocker Am Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (2001 digital remaster) Am Alton Ellis Black Man's Pride F Aluna George Your Drums, Your Love (Duke Dumont Remix) G# Amerie 1 Thing Ebm Amira My Desire (Dreem Teem Remix) Fm Amirali -

Beastie Boys Solid Gold Hits Mp3, Flac, Wma

Beastie Boys Solid Gold Hits mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Solid Gold Hits Country: US Released: 2005 MP3 version RAR size: 1358 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1839 mb WMA version RAR size: 1372 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 117 Other Formats: AIFF AC3 TTA AAC DXD DMF WAV Tracklist Hide Credits CD-1 So What'cha Want 3:37 CD-2 Brass Monkey 2:38 CD-3 Ch-Check It Out 3:10 CD-4 No Sleep Till Brooklyn 4:06 CD-5 Hey Ladies 3:48 CD-6 Pass The Mic 4:17 CD-7 An Open Letter To NYC 4:13 CD-8 Root Down 3:31 CD-9 Shake Your Rump 3:17 CD-10 Intergalactic 3:30 CD-11 Sure Shot 3:18 Body Movin' (Fatboy Slim Remix) CD-12 4:08 Engineer – Simon ThorntonProducer – Mario Caldato Jr.Remix – Fatboy Slim CD-13 Triple Trouble 2:43 CD-14 Sabotage 2:58 CD-15 Fight For Your Right 3:30 So What'cha Want DVD-1 3:38 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* Brass Monkey DVD-2 2:29 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* Ch-Check It Out DVD-3 5:06 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* No Sleep Till Brooklyn DVD-4 4:41 Film Director [Video Director] – Adam Dubin, Rick Menello Hey Ladies DVD-5 3:49 Other [Video Director] – Adam Bernstein Pass The Mic DVD-6 4:05 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* An Open Letter To NYC DVD-7 4:19 Other [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* Root Down DVD-8 3:34 Film Director [Video Director] – Evan Bernard Shake Your Rump DVD-9 3:38 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial Hörnblowér* Intergalactic DVD-10 4:34 Film Director [Video Director] – Nathanial -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

Song Name Artist

Sheet1 Song Name Artist Somethin' Hot The Afghan Whigs Crazy The Afghan Whigs Uptown Again The Afghan Whigs Sweet Son Of A Bitch The Afghan Whigs 66 The Afghan Whigs Cito Soleil The Afghan Whigs John The Baptist The Afghan Whigs The Slide Song The Afghan Whigs Neglekted The Afghan Whigs Omerta The Afghan Whigs The Vampire Lanois The Afghan Whigs Saor/Free/News from Nowhere Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 1 Afro Celt Sound System Inion/Daughter Afro Celt Sound System Sure-As-Not/Sure-As-Knot Afro Celt Sound System Nu Cead Againn Dul Abhaile/We Cannot Go... Afro Celt Sound System Dark Moon, High Tide Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 2 Afro Celt Sound System House Of The Ancestors Afro Celt Sound System Eistigh Liomsa Sealad/Listen To Me/Saor Reprise Afro Celt Sound System Amor Verdadero Afro-Cuban All Stars Alto Songo Afro-Cuban All Stars Habana del Este Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba le Gusta Afro-Cuban All Stars Fiesta de la Rumba Afro-Cuban All Stars Los Sitio' Asere Afro-Cuban All Stars Pío Mentiroso Afro-Cuban All Stars Maria Caracoles Afro-Cuban All Stars Clasiqueando con Rubén Afro-Cuban All Stars Elube Chango Afro-Cuban All Stars Two of Us Aimee Mann & Michael Penn Tired of Being Alone Al Green Call Me (Come Back Home) Al Green I'm Still in Love With You Al Green Here I Am (Come and Take Me) Al Green Love and Happiness Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green I Can't Get Next to You Al Green You Ought to Be With Me Al Green Look What You Done for Me Al Green Let's Get Married Al Green Livin' for You [*] Al Green Sha-La-La -

Beastie Boys Get It Together / Sabotage Mp3, Flac, Wma

Beastie Boys Get It Together / Sabotage mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Rock / Pop Album: Get It Together / Sabotage Country: UK Released: 1994 Style: Alternative Rock, Cut-up/DJ, Pop Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1428 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1918 mb WMA version RAR size: 1777 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 712 Other Formats: VOC MP1 AIFF AU VOX WMA XM Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Get It Together 4:07 2 Sabotage 3:00 Get It Together (Beastie Boys Remix) 3 4:07 Remix – Mario Caldato Jr. 4 Resolution Time 2:48 Credits Engineer – Mario Caldato Jr. (tracks: 1, 3) Producer – Beastie Boys, Mario Caldato Jr. Rap – Q Tip* (tracks: 1, 3) Written-By – Beastie Boys, J. Davis* (tracks: 1, 3) Notes In card wallet Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 724388142526 Matrix / Runout: 881425 2.1 EMI SWINDON Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Capitol Records, 7243 8 58185 6 Capitol Records, 7243 8 58185 6 Beastie Get It Together 1, Y 7243 8 Brooklyn Dust 1, Y 7243 8 US 1994 Boys (12", Single) 58185 6 1 Music, Grand 58185 6 1 Royal CDEMS (WS) 1 CDEMS (WS) 1 Beastie Get It Together Grand Royal, South , 7 243881 , 7 243881 1994 Boys (CD, Maxi, Car) Capitol Records Africa 554276 554276 Get It Together Beastie CDCLDJ 716 (CD, Single, Capitol Records CDCLDJ 716 UK 1994 Boys Promo) Get It Together Beastie Grand Royal, CL 716 (7", Single, Ltd, CL 716 UK 1994 Boys Capitol Records Gre) 7243 8 81425 4 Beastie Get It Together 7243 8 81425 4 Capitol Records UK 1994 0 Boys (Cass, Maxi) 0 Comments about Get It Together / Sabotage - Beastie Boys Brialelis Get It Together - (Beastie Boys Mix) is the same as the (A.B.A. -

The Beacon, October 21, 2004 Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) Special Collections and University Archives 10-21-2004 The Beacon, October 21, 2004 Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Florida International University, "The Beacon, October 21, 2004" (2004). The Panther Press (formerly The Beacon). 129. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper/129 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Football loses The Student Newspaper to Division I-A of Florida team. 8 International University THE BEACON Vol. 17, Issue 16 WWW.BEACONNEWSPAPER.COM October 21, 2004 Democrat says Bush policies ignore Latinos By C. JOEL MARINO News Editor As the war in Iraq makes the American public turn its attention to the Middle East, many feel U.S. policy has ignored other regions of the world in the last few years. In a lecture on Oct. 18 in the Uni- versity Park’s Graham Center Ballroom, Robert Menendez, Democratic congress- man for New Jersey, stated the ignorance of other world regions to be a major election year problem, especially when it comes to policies dealing with South PARTY ANIMALS: Christian Torres (center) of Panamanian band Rabanes performs at the annual Latin Fusion Explosion concert. America and the Caribbean. JEFFRIEY BARRY/THE BEACON The son of Cuban immigrants, Menen- dez is the chairman of the Democratic Caucus and the third-highest ranking Democrat in the U.S. -

Beastie Boys to the 5 Boroughs Mp3, Flac, Wma

Beastie Boys To The 5 Boroughs mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: To The 5 Boroughs Country: Russia Style: Pop Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1794 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1712 mb WMA version RAR size: 1391 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 988 Other Formats: FLAC AAC XM MIDI MOD VQF AAC Tracklist 1 Ch-Check It Out 3:12 2 Right Right Now Now 2:47 3 3 The Hard Way 2:48 4 Time To Build 3:12 5 Rhyme The Rhyme Well 2:47 6 Triple Trouble 2:43 7 Hey Fuck You 2:22 8 Oh Word? 3:00 9 That's It That's All 2:29 10 All Lifestyles 2:34 11 Shazam! 2:27 12 An Open Letter To NYC 4:19 13 Crawlspace 2:54 14 The Brouhaha 2:13 15 We Got The 2:27 Notes 10 pages booklet. Jewel case with transparent tray. ℗ 2004 The copyright in this recording is owned by Capitol Records, Inc. and Beastie Boys. © 2004 Capitol Records, Inc. and Beastie Boys. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 7 2435-70854-2 7 Barcode (String): 724357085427 Matrix / Runout: EMI UDEN 5708542 @ 1 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L046 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year To The 5 Boroughs CDP 72435 Beastie Capitol CDP 72435 (CD, Album, Copy US 2004 84571 0 0 Boys Records 84571 0 0 Prot., Enh, Dig) To The 5 Boroughs Beastie Capitol TOCP-66300 (CD, Album, Copy TOCP-66300 Japan 2004 Boys Records Prot.) To The 5 Boroughs EMI, Capitol Beastie 7243 5 70854 2 7 (CD, Album, Copy Records, 7243 5 70854 2 7 Canada 2004 Boys Prot.) Chrysalis To The 5 Boroughs CDP 72435 Beastie Capitol CDP 72435 (CD, Album, Copy US 2004 84571 0 0 Boys Records 84571 0 0 Prot., Enh, Jew) To The 5 Boroughs Beastie Capitol 7243 5 70856 2 5 (CD, Album, Enh, 7243 5 70856 2 5 Europe 2004 Boys Records Cle) Related Music albums to To The 5 Boroughs by Beastie Boys Beastie Boys - Ch-Check It Out Beastie Boys - Remote Control / 3 MCs & 1 DJ Beastie Boys - Triple Trouble Beastie Boys - The In Sound From Way Out! Beastie Boys - Remote Control Beastie Boys - Make Some Noise, Bboys! Beastie Boys - The Mix-Up Beastie Boys - BB Retail Listening Post Cd. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title (Aerosmith) 02)Nwa 10 Years I Dont Wanna Miss A Thing Real Niggas Don't Die Through The Iris (Busta Rhymes Feat Mariah 03 Waking Up Carey) If You Want Me To Stay Wasteland I Know What You Want (Remix) 100% Funk (Ricky Martin) 04 Play That Funky Music White Living La Vida Loca Behind The Sun (Ben Boy (Rose) Love Songs Grosse Mix) 101bpm Ciara F. Petey Eric Clapton - You Look 04 Johnny Cash Pablo Wonderful Tonight In The Jailhouse Goodies Lethal Weapon (Soplame.Com ) 05 11 The Platters - Only You Castles Made Of Sand (Live) Police Helicopter (Demo) (Vitamin C) 05 Johnny Cash 11 Johnny Cash Graduation (Friends Forever) Ring Of Fire Sunday Morning C .38 Special 06 112 Featuring Foxy Brown Caught Up In You Special Secret Song Inside U Already Know [Huey Lewis & The News] 06 Johnny Cash 112 Ft. Beanie Sigel I Want A New Drug (12 Inch) Understand Your Dance With Me (Remix) [Pink Floyd] 07 12 Comfortably Numb F.U. (Live) Nevermind (Demo) +44 07 Johnny Cash 12 Johnny Cash Baby Come On The Ballad Of Ir Flesh And Blood 01 08 12 Stones Higher Ground (12 Inch Mix) Get Up And Jump (Demo) Broken-Ksi Salt Shaker Feat. Lil Jon & Godsmack - Going Down Crash-Ksi Th 08 Johnny Cash Far Away-Ksi 01 Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Bl Lie To Me I Still Miss Som 09 Photograph-Ksi 01 Muddy Waters Out In L.A. (Demo) Stay-Ksi I Got My Brand On You ¼‚½‚©Žq The Way I Feel-Ksi 02 Another Birthday 13 Hollywood (Africa) (Dance ¼¼ºñÁö°¡µç(Savage Let It Shine Mix) Garden) Sex Rap (Demo) 02 Johnny Cash I Knew I Loved You 13 Johnny Cash The Legend -

Thomas Phleps

9/11 UND DIE FOLGEN IN DER POPMUSIK IV. EINE AUSWAHLDISKOGRAPHIE Thomas Phleps Die nachfolgende Diskographie bietet nur einen kleinen Ausschnitt aus der 9/11 und die Folgen betreffenden Musikproduktion. Nur in ganz geringem Umfang bspw. sind Songs der vor allem von Amateuren bis Semiprofis be- stückten Musikportale für den kostenlosen Download von MP3s oder anderen Audioformaten (wie MP3.com, Iuma.com, Soundclick.com oder Besonic. com) aufgeführt — hier zeigt sich am deutlichsten die Flüchtigkeit des Internets, da zahlreiche dieser immerhin rund 1300 Songs (und so manche der unten aufgeführten) u.a. durch den Wechsel der Besitzverhältnisse an der Domain MP3.com, dem größten dieser Portale, über ihre einstigen Adressen nicht mehr abrufbar sind (vgl. S. 64). Diese mitunter arg amateur- haften Musikproduktionen wurden vor allem in den ersten Monaten nach 9/11 und im Umfeld des Afghanistankrieges ins Netz gestellt; zu Zeiten der sich zuspitzenden Irakkrise resp. der US-Kriegsvorbereitungen, im Februar/ März 2003 also entwickelte sich das WorldWideWeb zu einer alternativen Publikationsmöglichkeit auch für die Profis, die ihre engagierten Protest- songs unzensiert, ohne kommerziellen Hintergrund und vorzugsweise im MP3-Format allen Interessierten über ihre eigenen Homepages und — sehr schnell — zahlreiche Musikportale meist im MP3-Format frei zugänglich machten. Die diskographischen Unterteilungen in Tribute, Pro War oder Anti War Songs dienen eher der Orientierung und wollen nicht die Songs in Schub- laden ablegen. Nicht selten auch sind diese Einordnungen weniger vom Song selbst als den ihn umgebenden Zuschreibungen bestimmt. Die diskographi- schen Angaben sortieren sich wie folgt: Interpret(en): Song- resp. Albumtitel (Tonträgerformat, Erscheinungs- datum resp. Kompositions- oder Aufnahmedatum) [Genre] [Internetadresse zu Musik und/oder Text oder auch nur zu weiterführenden Informationen; entfällt bei CD-Veröffentlichungen bekannter Interpreten]. -

Groove 5 • 2004

Nummer 5 • 2004 Sveriges största musiktidning Beastie Boys Groove 5 • 2004 Niccokick sidan 6 Att brinna är Tre frågor till Safari sidan 6 Språklig jämställdhet sidan 6 enda alternativet Omslag Skinny Puppy sidan 8 Tsuyoshi Ando Tacka Bush för det sidan 8 I en tv-sänd Nick Cave-dokumen- gör på sina hotellrum känns i sam- tär nyligen pratade Blixa Bargeld manhanget helt ointressant. Men Groove Ett subjektivt alfabet sidan 10 om hur man gör för att inte ätas hur Sonic Youth, Beastie Boys och Box 112 91 404 26 Göteborg Di Leva sidan 10 upp av myten om att vara rock- Di Leva uppfattar sin situation och stjärna. Det finns två val: antingen hur de formulerar sitt uppdrag vill Telefon 031–833 855 Ebon Tale sidan 12 så inser man att det finns annat som jag gärna få reda på. Därför kan Elpost [email protected] Kristoffer Janzon sidan 12 kan vara lika viktigt i livet eller så du läsa om dem i detta nummer av http://www.groove.se slutar man brinna. Det senare för- Groove. Men det är även intres- Quant sidan 13 utsätter självklart att man någon sant att uppmärksamma artister Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare Gary Andersson, [email protected] Slagsmålsklubben sidan 13 gång brunnit för det man gör, men i början av sin karriär. Därför är att man inte längre orkar bry sig. jag alltid spänd över vad som ska Redaktör Wendy sidan 13 Men visst är det skönt med artis- hamna under vår vinjett Blågult Niklas Simonsson, [email protected] The (International) ter som fortsätter att bry sig! Få Guld.