A Reading of the Autobiographies of Agassi and Sampras David Zilbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS CENTRE AGAINST APARTHEID co NOTES ANQ J0DMM. NTS* i%, FEB 1I 1986 September 1985 REGISTER OF SPORTS CONTACT WITH SOUTH AFRICA 1 July - 31 December 1984 rote: Pursuant to a decision Anartheid has been publishing with South Africa. in 1980, the Special Committee against semi-annual registers of sports contacts The present register, as the previous ones, contains: A list of sports exchanges with South Africa arranged by the code of sports; A list of sportmen and sportswomen who participated in sport events in South Africa, arranged by country. Names of persons who undertake not to engage in further sports events in South Africa will be deleted from the register.7 *All materiai in these Notes and Documents may be freely reprinted. Acknowledgement, together with a copy of the publication containing the reprint, would be appreciated. United Nations. New York 10017 7/85 85-24614 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ............. ............................ 1 South African propaganda .......... .................... 1 I. THE REALITY IN SOUTH AFRICA .... ................ ..... 2 A. Media reporting ........... ........................ 2 B. Laws and regulations ............ C. Co-operation with apartheid sport ............... 3 D. Sports in schools ........... ....................... 4 E. Cricket ............ ............................ 4 F. Football ................ ...........5 G. Golf ........ ....... .............5 H. Sailing ............. ............................ 5 I. Tennis . .......... ...... ...........5 II. SOUTH AFRICA AND THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT ..... ............ 6 III. INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION BY DECEPTION ..... ........... 7 IV. THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FEDERATION ...... .............. 8 V. INTERNATIONAL ACTION AGAINST APARTHEID SPORT .... ........ 8 VI. DELETIONS FROM THE REGISTER .......................... 10 A. The case of Mr. Walter Hadlee .................... .11 13. Clarification ......... ...................... .11 Annexes I. List of sports exchanges with South Africa from 1 July to 31 Jecember 1984 II. -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

Game, Set, Watched: Governance, Social Control and Surveillance in Professional Tennis

GAME, SET, WATCHED: GOVERNANCE, SOCIAL CONTROL AND SURVEILLANCE IN PROFESSIONAL TENNIS By Marie-Pier Guay A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November, 2013 Copyright © Marie-Pier Guay, 2013 Abstract Contrary to many major sporting leagues such as the NHL, NFL, NBA, and MLB, or the Olympic Games as a whole, the professional tennis industry has not been individually scrutinized in terms of governance, social control, and surveillance practices. This thesis presents an in-depth account of the major governing bodies of the professional tennis circuit with the aim of examining how they govern, control, constrain, and practice surveillance on tennis athletes and their bodies. Foucault’s major theoretical concepts of disciplinary power, governmentality, and bio-power are found relevant today and can be enhanced by Rose’s ethico-politics model and Haggerty and Ericson’s surveillant assemblage. However, it is also shown how Foucault, Rose, and Haggerty and Ericson’s different accounts of “modes of governing” perpetuate sociological predicaments of professional tennis players within late capitalism. These modes of surveillance are founded on a meritocracy based on the ATP and WTA rankings systems. A player’s ranking affects how he or she is governed, surveilled, controlled, and even punished. Despite ostensibly promoting tennis athletes’ health protection and wellbeing, the systems of surveillance, governance, and control rely on a biased and capitalistically-driven meritocracy that actually jeopardizes athletes’ health and contributes to social class divisions, socio- economic inequalities, gender discrimination, and media pressure. -

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest for Perfection

THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER THE ROGER FEDERER STORY Quest For Perfection RENÉ STAUFFER New Chapter Press Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic Originally published in Germany under the title “Das Tennis-Genie” by Pendo Verlag. © Pendo Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich and Zurich, 2006 Published across the world in English by New Chapter Press, www.newchapterpressonline.com ISBN 094-2257-391 978-094-2257-397 Printed in the United States of America Contents From The Author . v Prologue: Encounter with a 15-year-old...................ix Introduction: No One Expected Him....................xiv PART I From Kempton Park to Basel . .3 A Boy Discovers Tennis . .8 Homesickness in Ecublens ............................14 The Best of All Juniors . .21 A Newcomer Climbs to the Top ........................30 New Coach, New Ways . 35 Olympic Experiences . 40 No Pain, No Gain . 44 Uproar at the Davis Cup . .49 The Man Who Beat Sampras . 53 The Taxi Driver of Biel . 57 Visit to the Top Ten . .60 Drama in South Africa...............................65 Red Dawn in China .................................70 The Grand Slam Block ...............................74 A Magic Sunday ....................................79 A Cow for the Victor . 86 Reaching for the Stars . .91 Duels in Texas . .95 An Abrupt End ....................................100 The Glittering Crowning . 104 No. 1 . .109 Samson’s Return . 116 New York, New York . .122 Setting Records Around the World.....................125 The Other Australian ...............................130 A True Champion..................................137 Fresh Tracks on Clay . .142 Three Men at the Champions Dinner . 146 An Evening in Flushing Meadows . .150 The Savior of Shanghai..............................155 Chasing Ghosts . .160 A Rivalry Is Born . -

Physics of Tennis Lesson 4 Energy

The Physics of Tennis Lesson 4: Energy changes when a ball interacts with different surfaces Unit Overview: In this unit students continue to develop understanding of what can be at first glance a complicated system, the game of tennis. In this activity we have taken two components of the game of tennis, the ball and court, to see if we can model the interactions between them. This activity focuses on the energy interactions between ball and court. Objectives: Students will be able to- • Describe what forces interact when the ball hits a surface. • Understand what changes occur when potential and kinetic energy conversion is taking place within a system. At the high school level students should include connections to the concept of “work =FxD” and calculations of Ek = ½ 2 mv and Ep =mgh according to the conservation of energy principal. • Identify the types of energy used in this system. (restricted to potential & kinetic energy) • Comparative relative energy losses for typical court compositions. Lesson Time Required: Four class periods Next Generation Science/Common Core Standards: • NGSS: HS-PS3-1.Create a computational model to calculate the change in the energy of one component in a system when the change in energy of the other component(s) and energy flows in and out of the system are known. • CCSS.Math. Content: 8.F.B.4 Use functions to model relationships between quantities. • Construct a function to model a linear relationship between two quantities. Determine the rate of change and initial value of the function from a description of a relationship or from two (x, y) values, including reading these from a table or from a graph. -

Tennis Glory Ever Could

A CHAMPION’S MIND For my wife, Bridgette, and boys, Christian and Ryan: you have fulfilled me in a way that no number of Grand Slam titles or tennis glory ever could Introduction Chapter 1 1971–1986 The Tennis Kid Chapter 2 1986–1990 A Fairy Tale in New York Chapter 3 1990–1991 That Ton of Bricks Chapter 4 1992 My Conversation with Commitment Chapter 5 1993–1994 Grace Under Fire Chapter 6 1994–1995 The Floodgates of Glory Chapter 7 1996 My Warrior Moment Chapter 8 1997–1998 Wimbledon Is Forever Chapter 9 1999–2001 Catching Roy Chapter 10 2001–2002 One for Good Measure Epilogue Appendix About My Rivals Acknowledgments / Index Copyright A few years ago, the idea of writing a book about my life and times in tennis would have seemed as foreign to me as it might have been surprising to you. After all, I was the guy who let his racket do the talking. I was the guy who kept his eyes on the prize, leading a very dedicated, disciplined, almost monkish existence in my quest to accumulate Grand Slam titles. And I was the guy who guarded his private life and successfully avoided controversy and drama, both in my career and personal life. But as I settled into life as a former player, I had a lot of time to reflect on where I’d been and what I’d done, and the way the story of my career might impact people. For starters, I realized that what I did in tennis probably would be a point of interest and curiosity to my family. -

My Tennis Journey

Legends Series: Randall King – My Tennis Journey Randall King never set his sights explicitly on professional tennis. A four-time US Chinese National champion, his journey began from his hometown of Portland, Oregon, before he ventured throughout the Pacific Northwest, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, globetrotting on tour, then Taiwan, and ultimately landed in Hong Kong, a place where he has called home since joining Citibank here in 1980. His game found a new lease of life and immediately became an ever-present force on the local tennis scene, winning seven singles and nine doubles titles in local majors during a 6- year span. He made his presence felt immediately the first time he played Davis Cup for Hong Kong, when he helped steer a young local contingent, whose starters were barely out of high school, to its maiden victory in 1984. This is his story. Born on April 2, 1950, King grew up at a time when the undercurrent of the Chinese Exclusion Act was still prevalent in the States. It was a federal law passed in 1882 that prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers in the aftermath of the great influx caused by the Gold Rush. It was then subsequently extended several times before it was finally repealed in 1943. Although he did not experience this manner of push-back on a personal level, his early tennis years did not begin at the swanky country clubs, but instead at the public park tennis courts where he was a tag-along with his father to his regular get-togethers and he started to play the game against kids brought by other parents. -

The Tim & Tom Gullikson USTA/Midwest Section Scholarship

Tim & Tom Gullikson USTA/Midwest Section Scholarship Photo by Russ Adams Production Tim Gullikson Photo by Russ Adams Production Photo by Russ Adams Production Tom Gullikson Tom Gullikson Tim Gullikson Tim Gullikson was named the ATP Newcomer of the Year in 1977. He went on to capture four singles titles in his professional career and reached the finals in 11 singles events. He had a career-best year-end world ranking of number 18 in 1978 and was ranked among the top 50 in the world in six of seven years between 1977 and 1983. Tim teamed with his brother Tom to form the winningest brother doubles combination in the open era winning ten doubles titles together. They reached the Wimbledon Men’s Doubles Semifinals in 1982 and the Men’s Doubles Final in 1983. They also reached the US Open Men’s Doubles Semifinals in 1982. In all, Tim won 16 doubles titles and reached the finals in 13 others. He won five over-35 titles in 1991 including Wimbledon. He also won 21 over-35 doubles titles. Tim served as Pete Sampras’ coach helping Sampras to a number one world ranking. Tim passed away in May of 1996 from brain cancer. He was posthumously inducted into the USTA/Midwest Section Hall of Fame in 1997. Photograph by Russ Adams Production Tom Gullikson During his professional playing career, Tom Gullikson reached at least the third round of all four Grand Slam Championships, the doubles semifinals in three of the four Grand Slams, and he teamed with Manuela Maleeva to win the 1984 US Open Mixed Doubles Championship. -

Teams by Year

World TeamTennis - teams by year 1974 LEAGUE CHAMPIONS: DENVER RACQUETS EASTERN DIVISION Atlantic Section Baltimore Banners: Byron Bertram, Don Candy, Bob Carmichael, Jimmy Connors, Ian Crookenden, Joyce Hume, Kathy Kuykendall, Jaidip Mukerjea, Audrey Morse, Betty Stove. Boston Lobsters: Pat Bostrom, Doug Crawford, Kerry Melville, Janet Newberry, Raz Reid, Francis Taylor, Roger Taylor, Ion Tiriac, Andrea Volkos, Stephan Warboys. New York Sets: Fiorella Bonicelli, Carol Graebner, Ceci Martinez, Sandy Mayer, Charlie Owens, Nikki Pilic, Manuel Santana, Gene Scott, Pam Teeguarden, Virginia Wade, Sharon Walsh. Philadelphia Freedoms: Julie Anthony, Brian Fairlie, Tory Fretz, Billie Jean King, Kathy Kuykendall, Buster Mottram, Fred Stolle. COACH: Billie Jean King Central Section Cleveland Nets: Peaches Bartkowicz, Laura DuPont, Clark Graebner, Nancy Gunter, Ray Moore, Cliff Richey, Pat Thomas, Winnie Wooldridge. Detroit Loves: Mary Ann Beattie, Rosie Casals, Phil Dent, Pat Faulkner, Kerry Harris, Butch Seewagen, Lendward Simpson, Allan Stone. Pittsburgh Triangles: Gerald Battrick, Laura DuPont, Isabel Fernandez, Vitas Gerulaitis, Evonne Goolagong, Peggy Michel, Ken Rosewall. COACH: Ken Rosewall Toronto/Buffalo Royals: Mike Estep, Ian Fletcher, Tom Okker, Jan O’Neill, Wendy Overton, Laura Rossouw. WESTERN DIVISION Gulf Plains Section Chicago Aces: Butch Buchholz, Barbara Downs, Sue Eastman, Marcie Louie, Ray Ruffels, Sue Stap, Graham Stilwell, Kim Warwick, Janet Young. Florida Flamingos: Mike Belkin, Maria Esther Bueno, Mark Cox, Cliff Drysdale, Lynn Epstein, Donna Fales, Frank Froehling, Donna Ganz, Bettyann Stuart. Houston EZ Riders: Bill Bowrey, Lesley Bowrey, Cynthia Doerner, Peter Doerner, Helen Gourlay- Cawley, Karen Krantzcke, Bob McKinley, John Newcombe, Dick Stockton. Minnesota Buckskins: Owen Davidson, Ann Hayden Jones, Bob Hewitt, Terry Holladay, Bill Lloyd, Mona Guerrant Wendy Turnbull. -

![[Click Here and Type in Recipient's Full Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7514/click-here-and-type-in-recipients-full-name-2847514.webp)

[Click Here and Type in Recipient's Full Name]

News Release 11 November 2018 DJOKOVIC PRESENTED YEAR-END ATP WORLD TOUR NO. 1 TROPHY AT 2018 NITTO ATP FINALS LONDON — Novak Djokovic was today presented with the 2018 year-end ATP World Tour No. 1 trophy during an on-court presentation at the Nitto ATP Finals, the season finale at The O2 in London. The Serbian is one of only four players in ATP Rankings history (since 1973) to have clinched the year-end top spot on five (or more) occasions, joining Pete Sampras (six), Jimmy Connors and Roger Federer (both five times). Djokovic, who replaced Spain’s Rafael Nadal at No. 1 on 5 November, has completed a remarkable comeback to top form in 2018, capturing four titles—including two Grand Slams and two ATP World Tour Masters 1000s – from six tour-level finals. Aged 31 and six months, Djokovic is the oldest player to finish year-end No. 1 in ATP Rankings history. Having previously finished at the top in 2011-12, 2014-15, he is the second player — after Nadal (2008, 2010, 2013 and 2017) — with three stints as year-end No. 1. He is also the first player to be ranked outside the Top 20 and finish the same season at No. 1 in the history of the ATP Rankings. Russia’s Marat Safin was as low at No. 38 on 28 February 2000 before becoming No. 1 on 20 November that year, but he did not finish the season at No. 1. When Djokovic fell to No. 22 on 21 May 2018, it was his lowest ranking since he was No. -

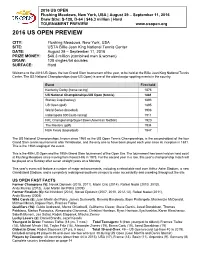

2016 Us Open Preview

2016 US OPEN Flushing Meadows, New York, USA | August 29 – September 11, 2016 Draw Size: S-128, D-64 | $46.3 million | Hard TOURNAMENT PREVIEW www.usopen.org 2016 US OPEN PREVIEW CITY: Flushing Meadows, New York, USA SITE: USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center DATE: August 29 – September 11, 2016 PRIZE MONEY: $46.3 million (combined men & women) DRAW: 128 singles/64 doubles SURFACE: Hard Welcome to the 2016 US Open, the last Grand Slam tournament of the year, to be held at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. The US National Championships (now US Open) is one of the oldest major sporting events in the country: Event First held Kentucky Derby (horse racing) 1875 US National Championships/US Open (tennis) 1881 Stanley Cup (hockey) 1893 US Open (golf) 1895 World Series (baseball) 1903 Indianapolis 500 (auto racing) 1911 NFL Championship/Super Bowl (American football) 1920 The Masters (golf) 1934 NBA Finals (basketball) 1947 The US National Championships, known since 1968 as the US Open Tennis Championships, is the second-oldest of the four Grand Slam tennis tournaments after Wimbledon, and the only one to have been played each year since its inception in 1881. This is the 136th staging of the event. This is the 49th US Open and the 195th Grand Slam tournament of the Open Era. The tournament has been held on hard court at Flushing Meadows since moving from Forest Hills in 1978. For the second year in a row, this year’s championship match will be played on a Sunday after seven straight years on a Monday. -

Last Year Tennis Rocketed to New Heights

by Mark Preston and 2001 Chris OdysseyATennis Nicholson Last year tennis rocketed to new heights. BEST MATCH: It was, simply, what it was always supposed to have been—brilliant. In one unforget- table evening, we remembered how the Pete Sampras-Andre Agassi “rivalry” had long ago been scripted. The two men had met 31 times coming into this US Open quarterfinal, with Sampras winning 17 of those meetings, but none had ever been as closely contested or as per- fectly played out as this. Here was Sampras, the game’s supreme server and Agassi, its greatest returner, not only excelling at their respective strengths but at each others’ as well. For three hours and 33 minutes, each man played at a level that seemed impossible to sustain—and yet somehow, each did. No breaks of serve, four tie-breaks, countless thrills. In the wee hours of the morning, the 6-7, 7-6, 7-6, 7-6 victory went to Sampras. There was no loser. T WAS A YEAR of comebacks and coming-out parties; win over Pete Sampras in the third round of the Ericsson Open in a year illuminated by the brilliance of a legion of young March. “He’s the real thing,” said Sampras of Roddick, who went on Istars and the undiminished glow of the game’s estab- to win three singles titles, reach the quarters of the US Open and fin- lished luminaries. ish the year ranked No. 14. In 2001, all across the country, people were talking ten- nis—and playing it. Participation and fan interest soared.