1 Transcript of a Pre-Concert Talk Given By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHOPIN and JENNY LIND

Icons of Europe Extract of paper shared with the Fryderyk Chopin Institute and Edinburgh University CHOPIN and JENNY LIND NEW RESEARCH by Cecilia and Jens Jorgensen Brussels, 7 February 2005 Icons of Europe TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. INFORMATION ON PEOPLE 4 2.1 Claudius Harris 4 2.2 Nassau W. Senior 5 2.3 Harriet Grote 6 2.4 Queen Victoria 7 2.5 Judge Munthe 9 2.6 Jane Stirling 10 2.7 Jenny Lind 15 2.8 Fryderyk Chopin 19 3. THE COVER-UP 26 3.1 Jenny Lind’s memoir 26 3.2 Account of Jenny Lind 27 3.3 Marriage allegation 27 3.4 Friends and family 27 4. CONCLUSIONS 28 ATTACHMENTS A Sources of information B Consultations in Edinburgh and Warsaw C Annexes C1 – C24 with evidence D Jenny Lind’s tour schedule 1848-1849 _______________________________________ Icons of Europe asbl 32 Rue Haute, B-1380 Lasne, Belgium Tel. +32 2 633 3840 [email protected] http://www.iconsofeurope.com The images of this draft are provided by sources listed in Attachments A and C. Further details will be specified in the final version of the research paper. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2003 Icons of Europe, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. Filed with the United States Copyright Office of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 1 Icons of Europe 1. INTRODUCTION This paper recapitulates all the research findings developed in 2003-2004 on the final year of Fryderyk Chopin’s life and his relationship with Jenny Lind in 1848-1849. Comments are invited by scholars in preparation for its intended publication as a sequel to the biography, CHOPIN and The Swedish Nightingale (Icons of Europe, Brussels, August 2003). -

SCRIPT LISZT & CHOPIN in PARIS.Pdf

LISZT & CHOPIN IN PARIS Written by John Mark Based on Actual Events Tel. (941) 276-1474 e-mail:[email protected] FIRST/2 /201 DRAFT 03 7 6 LISZT & CHOPIN IN PARIS 1 EXT. ISOLA BELLA. LAKE MAGGIORE - DAY 1 Three shadowy silhouettes in a small boat dip their oars into glassy surface of the lake heading towards the island. REPORTER and his ASSISTANT step on the ground, as the sun sets on the baroque garden in front of large castle. REPORTER (knocking loud on the front door) Hello.... Anyone there? BUTLER opens the door the reporter flashes his card. REPORTER (CONT’D) Good evening! I’m from Le Figaro and we came to see Mister Rachmaninoff. Butler closes the door half way. BUTLER He’s not here Sir. You just missed them. REPORTER Do you know where they are? BUTLER Yes. They’re leaving Europe. CUT TO 2 EXT. HÔTEL RITZ-PARIS - DAY 2 A crowd of PAPARAZZI floods vintage, four-door M-335 cabriolet as it comes to STOP. SERGEI RACHMANINOFF (65) and his wife NATALIA SATINA (62) exit the car and walk to the front door in the attempt to leave the flashing photographers behind them. TITLES ROLL: PARIS 1939. PAPARAZZO #1 (following them to the door) Welcome to the Ritz Monsieur Rachmaninoff. 2. PAPARAZZO #2 We heard you’re leaving Europe. CAMERA MOVES ALONG as CROWD in the lobby intensifies and paparazzi flash their cameras. As the composer and his wife pass through the door, the throng of paparazzi gets narrower while they keep snapping pictures following them to the elevator. -

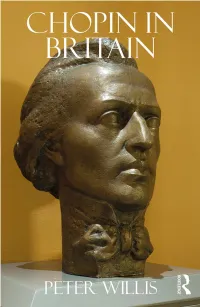

Chopin in Britain

Chopin in Britain In 1848, the penultimate year of his life, Chopin visited England and Scotland at the instigation of his aristocratic Scots pupil, Jane Stirling. In the autumn of that year, he returned to Paris. The following autumn he was dead. Despite the fascination the composer continues to hold for scholars, this brief but important period, and his previous visit to London in 1837, remain little known. In this richly illustrated study, Peter Willis draws on extensive original documentary evidence, as well as cultural artefacts, to tell the story of these two visits and to place them into aristocratic and artistic life in mid-nineteenth-century England and Scotland. In addition to filling a significant hole in our knowledge of the composer’s life, the book adds to our understanding of a number of important figures, including Jane Stirling and the painter Ary Scheffer. The social and artistic milieux of London, Manchester, Glasgow and Edinburgh are brought to vivid life. Peter Willis was an architect and Reader in the History of Architecture at Newcastle University. He completed a PhD in Music at Durham University in 2010. His pub- lications include Charles Bridgeman and the Landscape Garden, New Architecture in Scotland, and Chopin in Manchester. Chopin in Britain Peter Willis First published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Peter Willis The right of Peter Willis to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses CHOPIN IN BRITAIN Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 People, places, and activities Willis, Peter How to cite: Willis, Peter (2009) CHOPIN IN BRITAIN Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 People, places, and activities, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/179/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHOPIN IN BRITAIN Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837and 1848 PeoplQ,places, and activities Volume 2: Appendices, Bibliography, Personalia The copyright of this thesis restswith the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it shouldbe acknowledged. -

Paulina Pieńkowska

Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ No. 32 (4/2017), pp. 5–28 DOI 10.4467/23537094KMMUJ.17.008.7837 www.ejournals.eu/kmmuj Paulina Pieńkowska UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW The Role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin’s Life and in Preserving Memory and Legacy of the Composer Abstract The role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin’s life as well as in preserving his legacy is nowadays underestimated. Jane Stirling was not only Chopin’s pupil, but also his patron. She or- ganized a concert tour to England and Scotland for him and tried to support the composer financially. Moreover, she defrayed the costs of the composer’s funeral and erecting his gravestone. After his death, she focused on what Chopin had left passing away. It is thought that she purchased most of the items from his last flat; she acquired also the last piano the composer had played. She tried to protect the autograph manuscripts he had left, and attempted to arrange the publication of compositions that had been retained only in a sketch form. Keywords Jane Wilhelmina Stirling, Fryderyk Chopin, Romantic music, Chopin’s heritage 5 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ, No. 32 (1/2017) Nowadays, Jane Wilhelmina Stirling is almost forgotten. Common- ly, when we think about women that influenced Fryderyk Chopin’s life and art, we mention names of Konstancja Gładkowska, Ma- ria Wodzińska, George Sand, her daughter Solange Clésinger, Delfina Potocka or Marcelina Czartoryska. Meanwhile, Jane Stirling is not widely discussed in biographies of Chopin that are recognized as basic.1 She is usually mentioned as a person who partly caused the premature death of the composer as she organized his exhausting journey to England and Scotland, or as a student who unrequitedly loved Chopin. -

CHOPIN and HIS WORLD August 11–13 and 17–20, 2017

SUMMERSCAPE CHOPIN AND HIS WORLD August 11–13 and 17–20, 2017 BARD thank you to our donors The Bard Music Festival thanks its Board of Directors and the many donors who contributed so generously to The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Challenge Grant. We made it! Your support enabled us to complete the two-for-one match and raise $3 million for an endowment for the festival. Because of you, this unique festival will continue to present chamber and orchestral works, rediscovered pieces, talks and panels, and performances by emerging and favorite musicians for years to come. Bard Music Festival Mellon Challenge Donors Edna and Gary Lachmund Anonymous Alison L. and John C. Lankenau Helen and Roger Alcaly Glenda A. Fowler Law and Alfred J. Law Joshua J. Aronson Dr. Nancy Leonard and Dr. Lawrence Kramer Kathleen Augustine Dr. Leon M. and Fern Lerner John J. Austrian ’91 and Laura M. Austrian Mrs. Mortimer Levitt Mary I. Backlund and Virginia Corsi Catherine and Jacques Luiggi Nancy Banks and Stephen Penman John P. MacKenzie Matthew Beatrice Amy and Thomas O. Maggs Howard and Mary Bell Daniel Maki Bessemer National Gift Fund Charles Marlow Dr. Leon Botstein and Barbara Haskell Katherine Gould-Martin and Robert L. Martin Marvin Bielawski MetLife Foundation David J. Brown Kieley Michasiow-Levy Prof. Mary Caponegro ’78 Andrea and Kenneth L. Miron Anna Celenza Karl Moschner and Hannelore Wilfert Fu-Chen Chan Elizabeth R. and Gary J. Munch Lydia Chapin and David Soeiro Martin L. and Lucy Miller Murray Robert and Isobel Clark Phillip Niles Michelle R. Clayman Michael Nishball Prof. -

Chopin in Britain: Chopin's Visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 : People, Places and Activities

Durham E-Theses Chopin in Britain: Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 : people, places and activities. Willis, Peter How to cite: Willis, Peter (2009) Chopin in Britain: Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 : people, places and activities., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1386/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHOPIN IN BRITAIN Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837and 1848 People, places,and activities Volume 1: Text The copyright of this thesis restswith the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it shouldbe acknowledged. -

Paulina Pieńkowska the Role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin's Life and in Preserving Memory and Legacy Of

Paulina Pieńkowska The role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin’s life and in preserving memory and legacy of the composer Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ nr No. 32 (1), 5-28 2017 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ No. 32 (4/2017), pp. 5–28 DOI 10.4467/23537094KMMUJ.17.008.7837 www.ejournals.eu/kmmuj Paulina Pieńkowska UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW The Role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin’s Life and in Preserving Memory and Legacy of the Composer Abstract The role of Jane Wilhelmina Stirling in Fryderyk Chopin’s life as well as in preserving his legacy is nowadays underestimated. Jane Stirling was not only Chopin’s pupil, but also his patron. She or- ganized a concert tour to England and Scotland for him and tried to support the composer financially. Moreover, she defrayed the costs of the composer’s funeral and erecting his gravestone. After his death, she focused on what Chopin had left passing away. It is thought that she purchased most of the items from his last flat; she acquired also the last piano the composer had played. She tried to protect the autograph manuscripts he had left, and attempted to arrange the publication of compositions that had been retained only in a sketch form. Keywords Jane Wilhelmina Stirling, Fryderyk Chopin, Romantic music, Chopin’s heritage 5 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ, No. 32 (1/2017) Nowadays, Jane Wilhelmina Stirling is almost forgotten. Common- ly, when we think about women that influenced Fryderyk Chopin’s life and art, we mention names of Konstancja Gładkowska, Ma- ria Wodzińska, George Sand, her daughter Solange Clésinger, Delfina Potocka or Marcelina Czartoryska. -

An Analysis of Virtuosic Self-Accompanied Singing As a Historical Vocal Performance Practice

The Ideal Orpheus: An Analysis of Virtuosic Self-Accompanied Singing as a Historical Vocal Performance Practice Volume Two of Two Robin Terrill Bier Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Music September 2013 231 Contents Volume Two Contents, Volume Two 231 Appendix One. Documentation of Historical Self-Accompanied Singing 232 Newspapers and Periodicals 233 Personal Accounts 324 Literature 346 Historical Music Treatises 366 Appendix Two. Singers 374 Appendix Three. Repertoire 380 Appendix Four. Discography 401 Appendix Five. Developing a self-accompanied performance of 411 Paisiello’s ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ Conception 411 Preparation 412 Presentation 415 Performers experience 417 Audience response 417 Bibliography 418 232 Appendix One Documentation of Historical Self-Accompanied Singing This appendix catalogues evidence in primary sources that directly portrays self- accompaniment. When indirect evidence refers to a body of repertoire that is elsewhere documented having been performed self-accompanied by the same performer, or when the evidence refers to a performer or performance context known to have been exclusively self- accompanied, or the source provides specific useful context for understanding other self- accompanied performances, it may also be included here. In the case of George Henschel and Reynaldo Hahn in particular, it should be noted that while it can be assumed that any documented performance is self-accompanied, evidence that does not identify self- accompaniment explicitly or offer new contextual information may not be included. This appendix is organized according to four basic types of material: Newspapers and Periodicals (including concert advertisements and reviews, letters to the editor, obituaries and other published articles), Personal Accounts (including published and unpublished letters, diaries, autobiographies, memoirs and contemporary biographies), Literature (including novels, poems, plays, non-academic non-fiction, musical and theatrical texts and works), and Historical Music Treatises. -

Frederic Chopin As a Man and Musician, Volume 2

Frederic Chopin as a Man and Musician, Volume 2 Frederick Niecks Frederic Chopin as a Man and Musician, Volume 2 Table of Contents Frederic Chopin as a Man and Musician, Volume 2.............................................................................................1 Frederick Niecks............................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER XX. 1836¡838. .........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER XXI...........................................................................................................................................11 CHAPTER XXIII. JUNE TO OCTOBER, 1839.........................................................................................43 CHAPTER XXIV. 1839−1842....................................................................................................................53 CHAPTER XXV..........................................................................................................................................70 CHAPTER XXVI. 1843−1847....................................................................................................................85 CHAPTER XXVII.....................................................................................................................................110 CHAPTER XXVIII....................................................................................................................................125 -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Chopin in Britain: Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 : people, places and activities. Willis, Peter How to cite: Willis, Peter (2009) Chopin in Britain: Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837 and 1848 : people, places and activities., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1386/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CHOPIN IN BRITAIN Chopin's visits to England and Scotland in 1837and 1848 PeoplQ,places, and activities Volume 2: Appendices, Bibliography, Personalia The copyright of this thesis restswith the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it shouldbe acknowledged.