Rolling Valley Farmlands EP/Edit1/02.08.10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

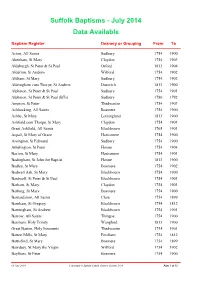

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Excursions 1997. Report and Notes on Some Findings. 19

EXCURSIONS1997 Reportand noteson somefindings 19 April. Philip Aitkens Ixworth, Garboldishamand North Lopham The towers of these three churches are believed to have been built by the 15th-century workshopof master masons,Aldrichof North Lopham, Norfolk. Acontract wasdrawn up in 1486between the churchwardens of Helmingham and Thomas Aldrich of North Lopham to construct their tower; today, it has a fine inscription at the base. North Lopham tower is believed,from evidencein wills,to have been commencedin 1479;an inscriptionby the same hand as that at Helminghamappears at mid-heighton the north side,but at the base isa band ofstone devices,flushwork-filled.Inscriptionsdated c.1480-1500are alsofound, for example, at Brockley(on the tower),Botesdale(over the north door) and Garboldisham(north porch), all by the same hand. Similardevicesin flushworkare to be found on many other churches c. 1460-80,especiallyat the basesof towers:those at Ixworth, BadwellAshand Elmswellform a notable group. SeealsoGarboldisham,Northwold,Fincham,NewBuckenham,Kenninghall and Mendlesharn. Other architectural features closelymatch, clear evidence of a common designer. These are mostlydatable by willsto c.1460-80. It is believedthat a new generation at the Aldrich workshop commences c. 1486, favouring inscriptions instead of flushwork devices. Acontract wasmade withThomas Aldrichto rebuild the east wallofThetford Priory, 1505-07. lxworth, St Mary'sChurch. The annual general meeting washeld here by kind permissionof the Revd P. Oliver. The tower was begun c. 1472, as evidenced by the 'Thomas Vyal' tile, commemorating the bequest of six marks by a prosperous localcarpenter in Decemberthat year,for workon the new`stepyr,and twotilesinscribedwiththe name ofWilliamDensy,Prior of the Augustinianhouse at Ixworth, 1467-84,one of them alsodated 1472. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

January 14 Mono Sectionbrn

Box River News Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green January 2014 Vol 14 No 1 A Very Merry Christmas and a Happy and Healthy New Year to you all Scrooge the Panto, see inside 3PR’S YVONNE HUGHES RETIRES SAND HILL DEVELOPMENT Dear Editor Parish Council Meeting 2nd December 2013 – in the School Hall Some 50 residents of the village attended this meeting to discuss the planning application for the development of the Sand Hill site. Both the Boxford Society and the YourBoxford groups submitted well thought out and professional objections to this site for affordable housing, based on existing regulations. Unfortunately none of our concerns were discussed nor were we able to put questions on the planning application to the Parish Council. It is a sad day when concerned residents who are anxious to work with the Councillors for the best outcome for villagers who are to be rehomed in Boxford, have been dismissed There were two residents who spoke in favour of the site, stating they were concerned their children would not be able to live in the village in the future. Details of our concerns and residents comments can be found on the Yourboxford.org website. If anyone still wants to add their concerns to Babergh, the end date for submitting letters is 17th December. Please write to: Mr. G. Chamberlain, quoting Application Number B/13/01200/FUL copy to Christine Thurlow who is the Corporate Manager – Development Management, at Babergh D.C. Council Offices, Corks Lane, Hadleigh IP7 6SJ. Alternately you can e-mail it to: [email protected] or [email protected] Sue Beven.Yourboxford.org Box River News Telephone: 01787 211507 Yvonne Hughes, one of 3PR responders has retired from the group. -

Babergh District Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Babergh District Council Consultation response from Babergh District Council Babergh District Council (BDC) considered the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft proposals for the warding arrangements in the Babergh District at its meeting on 21 November 2017, and made the following comments and observations: South Eastern Parishes Brantham & Holbrook – It was suggested that Stutton & Holbrook should be joined to form a single member ward and that Brantham & Tattingstone form a second single member ward. This would result in electorates of 2104 and 2661 respectively. It is acknowledged the Brantham & Tattingstone pairing is slightly over the 10% variation threshold from the average electorate however this proposal represents better community linkages. Capel St Mary and East Bergholt – There was general support for single member wards for these areas. Chelmondiston – The Council was keen to ensure that the Boundary Commission uses the correct spelling of Chelmondiston (not Chelmondistan) in its future publications. There were comments from some Councillors that Bentley did not share common links with the other areas included in the proposed Chelmondiston Ward, however there did not appear to be an obvious alternative grouping for Bentley without significant alteration to the scheme for the whole of the South Eastern parishes. Copdock & Washbrook - It would be more appropriate for Great and Little Wenham to either be in a ward with Capel St Mary with which the villages share a vicar and the people go to for shops and doctors etc. Or alternatively with Raydon, Holton St Mary and the other villages in that ward as they border Raydon airfield and share issues concerning Notley Enterprise Park. -

Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: Strategic Appraisal

Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocationsx Stage 1: strategic appraisal Final report Prepared by LUC October 2020 Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: strategic appraisal Project Number 11013 Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. Draft for review R. Brady R. Brady S. Orr 05.05.2020 M. Statton R. Howarth F. Smith Nicholls 2. Final for issue R. Brady S. Orr S. Orr 06.05.2020 3. Updated version with additional sites F. Smith Nicholls R. Brady S. Orr 12.05.2020 4. Updated version - format and typographical K. Kaczor R. Brady S. Orr 13.10.2020 corrections Bristol Land Use Consultants Ltd Landscape Design Edinburgh Registered in England Strategic Planning & Assessment Glasgow Registered number 2549296 Development Planning London Registered office: Urban Design & Masterplanning Manchester 250 Waterloo Road Environmental Impact Assessment London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment landuse.co.uk Landscape Management 100% recycled paper Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents HIA Strategic Appraisal October 2020 Contents Cockfield 18 Wherstead 43 Eye 60 Chapter 1 Copdock 19 Woolverstone 45 Finningham 62 Introduction 1 Copdock and Washbrook 19 HAR / Opportunities 46 Great Bicett 62 Background 1 East Bergholt 22 Great Blakenham 63 Exclusions and Limitations 2 Elmsett 23 Great Finborough 64 Chapter 4 Sources 2 Glemsford 25 Assessment Tables: Mid Haughley 64 Document Structure 2 Great Cornard -

Box River News Should Let Him Know How Outraged We Feel That Our Views Were Telephone: 01787 211507 E.Mail: Able to Be Completely Ignored

August 2020 Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green Vol 20 No 8 CBATESBoY ESTxATES PRLANNINiG AvPPLIeCATIrON BONXFORDe NEIwGHBOURs HOOD PLAN As I am sure you all know by now but on 17th June 2020, The dismay at the outcome of the Catesby Estates Planning Babergh’s Planning Committee approved Outline Planning Application, expressed by the Boxford Society, is certainly shared Permission for 64 houses on Sand Hill. by those working to produce Boxford’s Neighbourhood Plan. That Andrew Good, on behalf of the Boxford Society, Roger Loose, on work has inevitably been slowed but far from halted by Covid 19 behalf of the Parish Council and Bryn Hurren our District restrictions. We had planned to present ideas for sustaining our Councillor put up a valiant fight against this proposal – quite village by smaller housing developments, designed to fulfil local difficult in the 3 minutes allocated to them. However, various requirements and to be agreed at public meetings and eventually factors worked against them. by a referendum vote. The meeting was a virtual one with everyone in their own bubble. Whether or not the 64 dwelling development comes to pass, we This led to a rather fractured meeting as everyone wrestled with remain determined to proceed with producing the Neighbourhood the technology and this format did not lead to any meaningful Plan and to take our village with us in earmarking suitable discussion of the application itself. Most of the Committee locations for appropriate market and affordable housing and other seemed reluctant to approve – in fact no-one was even prepared to development while looking after our facilities and infrastructure second the motion so the Chairman had to do this - they were and laying down community led and agreed markers for the perhaps fearful of the repercussions of rejection as Babergh has future. -

7 Manningtree to Flatford and Return

o e o a S a d tr d e e t Recto ry ish Road Hill d Gan Mill Road Warren White Horse Road Wood Barn Hazel Orvi oad d R a Manningtrees to Flatford and return rd o 7 La o f R t n a l e m F a h M ann ingtree R Ded Map of walking routes o ad Braham wood B1070 Spooner's Flatfo Wood rd Road er Sto Riv ur Ba r b ste er e gh The Haugh lch Co Dedham Community Farm ane L Flatford Mill ll E Flatford ll i i s lk B H ffo abergh M s S Su e m N x uff o Ten lk dr B tha reet ing erg n St To Dedham h h ig o Bra H ex lt R Dedham s o s ad E A137 R Riv iv e B1029 e r r S S tour to u r Dedham B O N Forge Street ld River O A C r Judas Gap le o a Ma V w n nin 54 Gates m n gtree d a a S River Stour h t Road d o reet e R r D e r e st t s e e h y c wa h l se c au l o C o C e C h Park Farm T rs H Lane a ope Co l l F le Eas e t L t ill ane H e Great Eastern Main Lin e stle ain Lin a J M upes Greensm C Manningtree astern Manningtree ill H g ill n Great E ll Station i i r H d n e C T o Coxs t S m tation Ro ad a Ea n Ga st C ins La bo ne d h A Q ng Roa East ro u e Lo u v u een n T e g st r a he Ea M h s ad c n w L o ill a h y R H ue D Hill g r il n i He v o l l L e il a May's H th s x Dedham Co Heath Mil Long Road West l H Long Road East ill ad Lawford o Riverview D Church Manningtree B e hall R ar s d g h High School ge ate a C m g h u e L R r Co a n c ne o h a Hil d Road Colchester l e ill v rn Main Li i e r e iv H r D y D r a W t East te e ish a n rav d g u e Hun Cox's ld ters n Wa Cha Gre H se Lawford e d v oa M a Long R y C ich W A137 ea dwa rw ignall B a St t geshall -

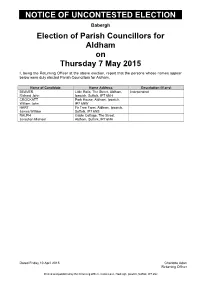

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Aldham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aldham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BEAVER Little Rolls, The Street, Aldham, Independent Richard John Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6NH CROCKATT Park House, Aldham, Ipswich, William John IP7 6NW HART Fir Tree Farm, Aldham, Ipswich, James William Suffolk, IP7 6NS RALPH Gable Cottage, The Street, Jonathan Michael Aldham, Suffolk, IP7 6NH Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Alpheton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alpheton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ARISS Green Apple, Old Bury Road, Alan George Alpheton, Sudbury, CO10 9BT BARRACLOUGH High croft, Old Bury Road, Richard Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BT KEMP Tresco, New Road, Long Melford, Independent Richard Edward Suffolk, CO10 9JY LANKESTER Meadow View Cottage, Bridge Maureen Street, Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BG MASKELL Tye Farm, Alpheton, Sudbury, Graham Ellis Suffolk, CO10 9BL RIX Clapstile Farm, Alpheton, Farmer Trevor William Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BN WATKINS 3 The Glebe, Old Bury Road, Ken Alpheton, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BS Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Assington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Assington. -

John Constable (1776-1837)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN John Constable (1776-1837) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Babergh Planning Committee, 06/12/2017 09:30

Public Document Pack COMMITTEE: PLANNING COMMITTEE VENUE: Hadleigh Town Hall, Market Place, Hadleigh DATE: Wednesday, 6 December 2017 9.30 am PLEASE NOTE CHANGE OF VENUE Members Sue Ayres Kathryn Grandon Simon Barrett John Hinton Peter Beer Michael Holt David Busby Adrian Osborne Luke Cresswell Stephen Plumb Derek Davis Nick Ridley Alan Ferguson Ray Smith The Council, members of the public and the press may record/film/photograph or broadcast this meeting when the public and the press are not lawfully excluded. Any member of the public who attends a meeting and objects to being filmed should advise the Committee Clerk. AGENDA PART 1 ITEM BUSINESS Page(s) 1 SUBSTITUTES AND APOLOGIES Any Member attending as an approved substitute to report giving his/her name and the name of the Member being substituted. To receive apologies for absence. 2 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Members to declare any interests as appropriate in respect of items to be considered at this meeting. 3 TO RECEIVE NOTIFICATION OF PETITIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE COUNCIL'S PETITION SCHEME ITEM BUSINESS Page(s) 4 QUESTIONS BY THE PUBLIC To consider questions from, and provide answers to, the public in relation to matters which are relevant to the business of the meeting and of which due notice has been given in accordance with the Committee and Sub-Committee Procedure Rules. 5 QUESTIONS BY COUNCILLORS To consider questions from, and provide answer to, Councillors on any matter in relation to which the Committee has powers or duties and of which due notice has been given in accordance with the Committee and Sub-Committee Procedure Rules. -

Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green Vol 19 No 8 RBEV Roob Mxov ESR in Iver News

August 2019 Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green Vol 19 No 8 RBEV RoOB MxOV ESR IN iver News ‘Bishop’s Move’! Revd Rob standing in front of the removals van outside the rectory in Boxford after he moved from Orpington to Boxford on 10th July. In welcoming Rob and his family to the benefice, we hope that his next ‘bishop’s move’ won’t occur for many years yet! TEAM ITFC CYCLE TO AMSTERDAM FOR PROSTATE CHARITY INSTITUTION AND INDUCTION of THE REVD ROBERT PARKER-McGEE as RECTOR OF THE BOX RIVER BENEFICE Tuesday 20 August 2019 at 7.30 pm St Lawrenceʼs Church, Little Waldingfield Guests at Stoke by Nayland Hotel, were joined by a few familiar faces on Friday 7th June, as former ITFC midfielder Simon Milton and his team of ALL ARE WELCOME TO THIS SERVICE charity cyclists rode in for lunch on their way from Ipswich to Amsterdam. WHEN ROB IS FORMALLY COMMISSIONED The annual charity bike ride in aid of Prostate Cancer UK, sees teams of fans and former professional footballers cycle from as far afield as London and TO START HIS MINISTRY AMONG US Yorkshire to Amsterdam. Team ITFC, which comprised of 21 riders including Town legends Titus DO COME ! Bramble and Alan Lee, set off from Ipswich on Friday 7th June. Cycling across the East Anglian countryside on Friday, the team stopped at the Hotel Refreshments will be served after the service. to fill up on an energising lunch, before setting off to Harwich where they arrived safely (though a little wet!) on Friday evening.