Native Hawaiians in the Criminal Justice System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

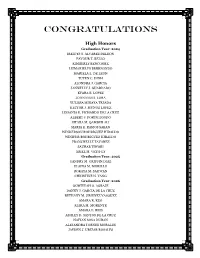

Congratulations

CONGRATULATIONS High Honors Graduation Year: 2024 IREIDYS Y. ALVAREZ DELEON FAVOUR T. BELLO KIMBERLY BENCOSME LIZMARIELYS BERREONDO MARIELA L. DE LEON TUYEN C. DINH ALONDRA J. GARCIA JANNELLY J. GUARDADO KYARA E. LOPEZ JOHNANGEL LORA YULISSA MINAYA TEJADA HECTOR J. MUNOZ LOPEZ LISSANIA E. PICHARDO DE LA CRUZ ALBERT J. PORTUHONDO SITARA M. QAMBER ALI MARIA E. RAMOS SABAN WINDERSON RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO WINIFER RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO FRANCHELLE TAVAREZ SAURAB TIWARI ARIEL M. VETH-LY Graduation Year: 2025 YANDRY M. GRIFFIN DIAZ ELAINA M. MORILLO ROKAYA M. SAHWAN CHRISTINE N. YANG Graduation Year: 2026 QOWIYYAH O. AGBAJE DANNY J. GARCIA DE LA CRUZ BETHANY M. JIMENEZ VASQUEZ AMARA R. KEO KIARA M. MORENTE AMARA E. REIS ASHLEY D. SANTOS DE LA CRUZ NAIYAN SOSA DURAN ALEJANDRA TORNES MORALES JAYDEN J. URIZAR ROSALES Honors Graduation Year: 2024 JOSELYN E. ALONZO XAVIEA S. BROWN PRECIOUS F. BUWEE WILBERT CABRAL GARCIA KALIYAN N. CHHUN JUANA CHIJAL JESSICA A. CHOCOJ CHALI DOMINGO COLAJ COLAJ MARIALYS I. CRUZ ASHLEY M. DE LA CRUZ ARIAS ARDENIS J. DEL ROSARIO GIANA N. DICENZO BRIANNA M. DOMINGUEZ FRIAS SOMALY DONG OSMERY ESTRELLA VARGAS ERICA O. FELIX HERRERA EDUARDO J. GIL ALFONSO BRYAN M. GIRON LUX VILMA GODINEZ SEBASTIANA JERONIMO ALONZO HENRY L. JOHNSON IV TATYANA JOHNSON KRISSBEILY MARTE FERREIRA GEARA D. MATOS DIEGO A. NAVAS ORTES OLIVIER NGABONZIZA MANUELA NUNEZ HERNANDEZ AMBER K. O'BRIEN NICERLIS OLIVO NUNEZ ANDERSON E. ORTEGA-LOPEZ YENEDELI E. PENA GUZMAN FRANCISCO PEREZ RAMOS RENE G. REYES EMILY A. RINDA BETHZY M. ROBLES URIZAR CRISTIAN D. ROSALES HERNANDEZ JASON S. RUSH JAMES D. SEFFENS III GENESIS SOSA ALEXANDER SUAREZ LIZZETTE M. -

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

2010 Hyundai Genesis

2010 HYUNDAI_GENESIS If you’re reading this brochure, chances are you’re the kind of automotive enthusiast who, instead of simply opening your wallet and adding a status trophy to your garage, prefers to open something else: Your mind. It’s a refreshing attitude that often leads you to discover truly rewarding experiences, from new and unexpected sources. Like Genesis, from Hyundai. Nobody was looking for Hyundai to build a luxury car that would challenge the automotive elite. But we did. Nobody expected us to benchmark the industry’s best, then apply the art and science needed to meet those marks. But we did. Nobody thought we’d charm the pants off a jury of North America’s most esteemed automotive journalists, or be named "The Most Appealing Midsize Premium Car" in 2009 by J.D. Power and Associates.1 But we did. And by doing what few people expected of us, we now find ourselves as a car company that a lot of people are starting to think about in a whole new way. It’s 2010. Welcome to Hyundai. 1 The Hyundai Genesis received the highest numerical score among midsize premium cars in the proprietary J.D. Power and Associates 2009 Automotive Performance Execution and Layout Study.SM Study based on responses from 80,930 new-vehicle owners, measuring 245 models and measures opinions after 90 days of ownership. Proprietary study results are based on experiences and perceptions of owners surveyed in February-May 2009. Your experiences may vary. Visit jdpower.com. geNesIS 3.8 IN TItaNIUM GRay metallIC MEASURE GENESIS AGAINST OTHER LUXURY SEDANS. -

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of Life's Deepest Mysteries Are Examined In

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of life’s deepest mysteries are examined in Bible stories. Through the centuries, for example, many have tried to make sense out of the narrative recorded in Genesis 22, one of the darkest, most difficult stories that humans have ever told each other. This account begins with a shout. It’s only one word long. Abraham is at home with his wife, his servants. We don’t know what he’s doing at this moment. It’s probably an ordinary day. When suddenly Abraham hears a voice. The voice says to him one word: “Abraham!” This is not just a voice. This is the voice of God, the Creator of the Universe calling to one man, to Abraham. Not for the first time, not at all. When Abraham was younger, God appeared to him and told him to leave his home, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham to go to a strange land, which he did. And then God and Abraham exchanged promises, and made a covenant together, and God told Abraham to send his first son Ishmael away into the desert, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham that he had a plan to destroy the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. This time Abraham argued with God. They went back and forth – Abraham and God. “Can’t we save those cities, or some people in those cities, or anyone in those cities?” Later God sent angels to tell of the coming of Isaac. So it wasn’t completely out of the ordinary when God came to where Abraham was and called to him. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

Genesis Sample Return

NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION Genesis Sample Return Press Kit September 2004 Media Contacts Donald Savage Policy/program management 202/358-1727 Headquarters, [email protected] Washington, D.C. DC Agle Genesis mission 818/393-9011 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, [email protected] Pasadena, Calif. Robert Tindol Principal investigator 626/395-3631 California Institute of Technology [email protected] Pasadena, Calif. Contents General Release ……................……………………………….........................………..……....… 3 Media Services Information …………………………….........................................………..…….... 5 Quick Facts…………………………………………………….......................................………....…. 6 Mysteries of the Solar Nebula ........………...…………………………......................................……7 Solar Studies Past and Present ...................................................................................... 8 NASA's Discovery Program .......................................................................................... 10 Mission Overview….………...…………...…………………………....................................…….... 12 Mid-Air Retrievals........................................................................................................... 14 Sample Return Missions ................................................................................................ 15 Spacecraft ………………………………………………………………......................................…. 26 Science Objectives ………………………………………………………....................................…. 33 The Solar Corona and -

Genesis, Evolution, and the Search for a Reasoned Faith

GENESIS EVOLUTION AND THE SEARCH FOR A REASONED FAITH Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Brian G. Henning Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu Ryan Taylor 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 3 1/3/11 12:57 PM Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover art royalty free from iStock Copyright © 2011 by Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ; Brian G. Henning; Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu; and Ryan Taylor. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. The scriptural quotations contained herein, with the exception of author transla- tions in chapter 1, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible: Catho- lic Edition. Copyright © 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 7031 (PO2844) ISBN 978-0-88489-755-2 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 4 1/3/11 12:57 PM c ontents Introduction ix .1 Genesis 1 Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Why Read the Bible in the First Place? 1 A Faithful and Rational Reading of the Bible 6 Oral Tradition and the Composition of the Bible 6 Two Stories, Not One 8 “Cosmogony” and the Ancient Near East 11 Genesis 2–3: The Yahwist Account 12 Disaster: The Babylonian Exile 27 Genesis 1: The Priestly Account 31 .2 Scientific Knowledge and Evolutionary Biology 41 Ryan Taylor Science and Its Methodology 41 The History of Evolutionary Theory 44 The Mechanisms of Evolution 46 Evidence for Evolution 60 Limits of Scientific Knowledge 64 Common Arguments against Evolution from Creationism and Intelligent Design 65 3. -

Genesis (In the Beginning...) Written By: Dennis Byrd

Genesis (In the Beginning...) written by: Dennis Byrd Spoken Intro: In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth Then the earth was without form and void And darkness was upon the face of the deep And the spirit of God - - moved upon the face of the waters. Musical Intro (4x) Unison: Genesis, Genesis, Genesis, Genesis (4x) (Parts): In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth SPOKEN: God! Musical Interlude (4x) Unison: Genesis, Genesis, Genesis, Genesis (4x) (Parts): Then the earth was without form and void And darkness was upon…the face of the deep And the spi-rit of God - - Moved upon the face of the waters. Musical Interlude (2x) Basses: Then God said Tenors: Then God said Altos: Then God said Sopranos: Then God said All: Let..there be light! Basses: And there was…light! Basses: And God saw the light Tenors: And God saw the light Altos: And God saw the light Sopranos: And God saw the light Basses: And...it…was……good! Musical Interlude (2x) Then God divided the light from the darkness The light He called day The darkness He called night And the evening and morning was the first day (2x) SPOKEN: And God said “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters” Choir: Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters SPOKEN: And God made the firmament Choir: Yes He did! SPOKEN: And God divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament And divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament SPOKEN: And God said “Let there -

GENESIS: an Agent-Based Model of Interdomain Network Formation, Traffic flow and Economics

GENESIS: An agent-based model of interdomain network formation, traffic flow and economics Aemen Lodhi Amogh Dhamdhere Constantine Dovrolis School of Computer Science CAIDA School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of California San Diego Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—We propose an agent-based network formation however, can have a global impact on the economic viability model for the Internet at the Autonomous System (AS) level. of all ASes and the structure of the Internet. The proposed model, called GENESIS, is based on realistic The Internet remains in a persistent state of flux subject to provider and peering strategies, with ASes acting in a myopic and decentralized manner to optimize a cost-related fitness function. changes in various exogenous factors. How will the Internet GENESIS captures key factors that affect the network formation change due to consolidation of content [1], large penetra- dynamics: highly skewed traffic matrix, policy-based routing, ge- tion of video streaming, falling transit prices [2], expanding ographic co-location constraints, and the costs of transit/peering geographic footprint of content providers [3], cheap local agreements. As opposed to analytical game-theoretic models, availability of peering infrastructure at IXPs [4]? We propose which focus on proving the existence of equilibria, GENESIS is a computational model that simulates the network formation a computational agent-based network formation model, called process and allows us to actually compute distinct equilibria (i.e., “GENESIS”, as a tool to study such questions. GENESIS is networks) and to also examine the behavior of sample paths modular and easily extensible, allowing researchers to exper- that do not converge. -

Ilwu/Pma Joint Disclaimer Los Angeles / Long Beach Casual Processing List

ILWU/PMA JOINT DISCLAIMER LOS ANGELES / LONG BEACH CASUAL PROCESSING LIST Attached is the List of those selected in the February 7, 2017 through March 29, 2017 random draw for potential processing toward Identified Casual status in the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach. The List will be used in sequence to fill Los Angeles/Long Beach’s need for new casuals. The Joint Port Labor Relations Committee (JPLRC) shall immediately process all ranked applicants from the list after which the list shall be terminated. Any names not initially drawn shall be purged from the process and individuals shall have no rights to consideration for casual application but shall be afforded equal opportunity with others, should a new list be established. Those to whom processing may be offered will be contacted if and when they will be offered testing for potential casual work. Candidates who satisfy all screening and testing requirements will become eligible for placement on the Identified Casual List from which longshore work is dispatched. Make sure you read and understand the full Disclaimer stated below. Submitting a postcard, interest card, or application, having a card selected in a draw, having a card sequenced and placed on a posted List, being contacted for testing/processing, and the stated procedures for casual processing do not offer or guarantee processing, employment or continued employment, particular procedures (including testing or retesting) or promotion. No reliance should be placed upon any of these steps, none of which forms a contract or creates any binding obligations upon PMA or ILWU towards you. The parties to the governing collective bargaining agreement (the “Pacific Coast Longshore Contract Document,” PCLCD), through the JPLRCs may, by joint agreement and in their discretion, at any time without notice, change or revoke the procedures for hiring, promotion, and employment in the longshore industry. -

“Amphan” Into a Super Cyclone?

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 3 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0033.v1 Did COVID-19 lockdown brew “Amphan” into a super cyclone? V. Vinoj* and D. Swain School of Earth, Ocean and Climate Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar *Email: [email protected] The world witnessed one of the largest lockdowns in the history of mankind ever, spread over months in an attempt to contain the contact spreading of the novel coronavirus induced COVID-19. As billions around the world stood witness to the staggered lockdown measures, a storm brewed up in the urns of the rather hot Bay of Bengal (BoB) in the Indian Ocean realm. When Thailand proposed the name “Amphan” (pronounced as “Um-pun” meaning ‘the sky’), way back in 2004, little did they realize that it was the christening of the 1st super cyclone (Category-5 hurricane) of the century in this region and the strongest on the globe this year. At the peak, Amphan clocked wind speeds of 168 mph (Joint Typhoon Warning Center) with the pressure drop to 925 h.Pa. What started as a depression in the southeast BoB at 00 UTC on 16th May 2020 developed into a Super Cyclone in less than 48 hours and finally made landfall in the evening hours of 20th May 2020 through the Sundarbans between West Bengal and Bangladesh. Did the impact of the COVID-19 induced lockdown drive an otherwise typical pre-monsoon tropical depression into a super cyclone? Global Warming and Tropical Cyclones Tropical cyclones are primarily fueled by the heat released by the oceans. -

Presentation to Department of Finance

Goldman Sachs Energy Credit Virtual Field Trip March 2021 Disclosures & Company Information Genesis Energy, L.P. NYSE: GEL Investor Relations Contact Common Unit Market Value ~$1.2 billion(a) [email protected] (713) 860-2500 Convertible Preferred Equity ~$0.9 billion(a) Corporate Headquarters Enterprise Value ~$5.4 billion(a) 919 Milam Street, Suite 2100 Annualized Common Unit Distribution $0.60 per unit Houston, TX 77002 Forward-Looking Statements This presentation includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 21A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Exchange Act of 1934 as amended. Except for the historical information contained herein, the matters discussed in this presentation include forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements are based on the Partnership’s current assumptions, expectations and projections about future events, and historical performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. Although Genesis believes that the assumptions underlying these statements are reasonable, investors are cautioned that such forward-looking statements are inherently uncertain and necessarily involve risks that may affect Genesis’ business prospects and performance, causing actual results to differ materially from those discussed during this presentation. Genesis’ actual current and future results may be impacted by factors beyond its control. Important risk factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from Genesis’ expectations are discussed in Genesis’ most recently filed reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Genesis undertakes no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information or future events. This presentation may include non-GAAP financial measures.