Chapter 3 the Copernican Revolution Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scienza E Cultura Universitalia

SCIENZA E CULTURA UNIVERSITALIA Costantino Sigismondi (ed.) ORBE NOVUS Astronomia e Studi Gerbertiani 1 Universitalia SIGISMONDI, Costantino (a cura di) Orbe Novus / Costantino Sigismondi Roma : Universitalia, 2010 158 p. ; 24 cm. – ( Scienza e Cultura ) ISBN … 1. Storia della Scienza. Storia della Chiesa. I. Sigismondi, Costantino. 509 – SCIENZE PURE, TRATTAMENTO STORICO 270 – STORIA DELLA CHIESA In copertina: Imago Gerberti dal medagliere capitolino e scritta ORBE NOVVS nell'epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II a S. Giovanni in Laterano (entrambe le foto sono di Daniela Velestino). Collana diretta da Rosalma Salina Borello e Luca Nicotra Prima edizione: maggio 2010 Universitalia INTRODUZIONE Introduzione Costantino Sigismondi L’edizione del convegno gerbertiano del 2009, in pieno anno internazionale dell’astronomia, si è tenuta nella Basilica di S. Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri il 12 maggio, e a Seoul presso l’università Sejong l’11 giugno 2009. La scelta della Basilica è dovuta alla presenza della grande meridiana voluta dal papa Clemente XI Albani nel 1700, che ancora funziona e consente di fare misure di valore astrometrico. Il titolo di questi atti, ORBE NOVUS, è preso, come i precedenti, dall’epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II in Laterano, e vuole suggerire il legame con il “De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium” di Copernico, sebbene il contesto in cui queste parole sono tratte vuole inquadrare Gerberto nel suo ministero petrino come il nuovo pastore per tutto il mondo: UT FIERET PASTOR TOTO ORBE NOVVS. Elizabeth Cavicchi del Massachussets Institute of Technology, ha riflettuto sulle esperienze di ottica geometrica fatte da Gerberto con i tubi, nel contesto contemporaneo dello sviluppo dell’ottica nel mondo arabo con cui Gerberto era stato in contatto. -

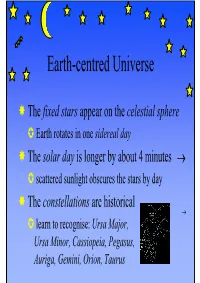

Earth-Centred Universe

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

The Longitude of the Mediterranean Throughout History: Facts, Myths and Surprises Luis Robles Macías

The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and surprises Luis Robles Macías To cite this version: Luis Robles Macías. The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and sur- prises. E-Perimetron, National Centre for Maps and Cartographic Heritage, 2014, 9 (1), pp.1-29. hal-01528114 HAL Id: hal-01528114 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01528114 Submitted on 27 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. e-Perimetron, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2014 [1-29] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 Luis A. Robles Macías* The longitude of the Mediterranean throughout history: facts, myths and surprises Keywords: History of longitude; cartographic errors; comparative studies of maps; tables of geographical coordinates; old maps of the Mediterranean Summary: Our survey of pre-1750 cartographic works reveals a rich and complex evolution of the longitude of the Mediterranean (LongMed). While confirming several previously docu- mented trends − e.g. the adoption of erroneous Ptolemaic longitudes by 15th and 16th-century European cartographers, or the striking accuracy of Arabic-language tables of coordinates−, we have observed accurate LongMed values largely unnoticed by historians in 16th-century maps and noted that widely diverging LongMed values coexisted up to 1750, sometimes even within the works of one same author. -

The Sundial Cities

The Sundial Cities Joel Van Cranenbroeck, Belgium Keywords: Engineering survey;Implementation of plans;Positioning;Spatial planning;Urban renewal; SUMMARY When observing in our modern cities the sun shade gliding along the large surfaces of buildings and towers, an observer can notice that after all the local time could be deduced from the position of the sun. The highest building in the world - the Burj Dubai - is de facto the largest sundial ever designed. The principles of sundials can be understood most easily from an ancient model of the Sun's motion. Science has established that the Earth rotates on its axis, and revolves in an elliptic orbit about the Sun; however, meticulous astronomical observations and physics experiments were required to establish this. For navigational and sundial purposes, it is an excellent approximation to assume that the Sun revolves around a stationary Earth on the celestial sphere, which rotates every 23 hours and 56 minutes about its celestial axis, the line connecting the celestial poles. Since the celestial axis is aligned with the axis about which the Earth rotates, its angle with the local horizontal equals the local geographical latitude. Unlike the fixed stars, the Sun changes its position on the celestial sphere, being at positive declination in summer, at negative declination in winter, and having exactly zero declination (i.e., being on the celestial equator) at the equinoxes. The path of the Sun on the celestial sphere is known as the ecliptic, which passes through the twelve constellations of the zodiac in the course of a year. This model of the Sun's motion helps to understand the principles of sundials. -

Lecture 25.Key

Astronomy 330: Extraterrestrial Life This class (Lecture 25): Evolution of Worldview Sean Sarcu Saloni Sheth ! ! Next Class: Lifetime Vincent Abejuela Cassandra Jensen Music: Astronomy – Metallica 2 x 2 page pdf articles due next Tues Drake Equation Frank That’s 2.7 intelligent systems/year Drake N = R* × fp × ne × fl × fi × fc × L # of # of Star Fraction of Fraction advanced Earthlike Fraction on Fraction that Lifetime of formation stars with that civilizations planets per which life evolve advanced rate planets commun- we can system arises intelligence civilizations icate contact in our Galaxy today 30 0.8 4 x 0.47 0.2 0.3 comm./ yrs/ stars/ systems/ = 1.88 life/ intel./ intel. comm. yr star planets/ planet life system • Requires civilization to undergo three steps: 1. A correct appreciation of the size and nature of the Worldview Universe 2. A realization of their place in the Universe 3. A belief that the odds for life are reasonable. The beings of Q’earth must have taken their Q’astro Intelligent ET Life must want to communicate with us 330 class and came up with a good number of communicable civilizations in the Q’drake This means they MUST equation. believe in the possibility of us (and other ET life) Requirements: ! 1) Understand size and scale of the cosmos ASTR 330 2) Realize their place in the cosmos 3) Believe the odds for life elsewhere are reasonable Alien 3 Our Worldview First worldview: Earth Centric Why? Natural observations imply we are stationary 4 • The Mayans computed the length of year to within a few Ancient Astronomy seconds (0.001%). -

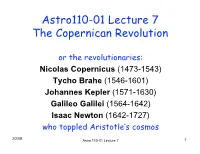

Astro110-01 Lecture 7 the Copernican Revolution

Astro110-01 Lecture 7 The Copernican Revolution or the revolutionaries: Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) Isaac Newton (1642-1727) who toppled Aristotle’s cosmos 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 1 Recall: The Greek Geocentric Model of the heavenly spheres (around 400 BC) • Earth is a sphere that rests in the center • The Moon, Sun, and the planets each have their own spheres • The outermost sphere holds the stars • Most famous players: Aristotle and Plato 2/2/09 Aristotle Plato Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 2 But this made it difficult to explain the apparent retrograde motion of planets… Over a period of 10 weeks, Mars appears to stop, back up, then go forward again. Mars Retrograde Motion 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 3 A way around the problem • Plato had decreed that in the heavens only circular motion was possible. • So, astronomers concocted the scheme of having the planets move in circles, called epicycles, that were themselves centered on other circles, called deferents • If an observation of a planet did not quite fit the existing system of deferents and epicycles, another epicycle could be added to improve the accuracy • This ancient system of astronomy was codified by the Alexandrian Greek astronomer Ptolemy (A.D. 100–170), in a book translated into Arabic and called Almagest. • Almagest remained the principal textbook of astronomy for 1400 years until Copernicus 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 4 So how does the Ptolemaic model explain retrograde motion? Planets really do go backward in this model. -

1 the Equatorial Coordinate System

General Astronomy (29:61) Fall 2013 Lecture 3 Notes , August 30, 2013 1 The Equatorial Coordinate System We can define a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Just like we can specify the latitude and longitude of a place on Earth, we can specify the coordinates of a star relative to a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Look at Figure 1.5 of the textbook for a definition of this coordinate system. The Equatorial Coordinate System is similar in concept to longitude and latitude. • Right Ascension ! longitude. The symbol for Right Ascension is α. The units of Right Ascension are hours, minutes, and seconds, just like time • Declination ! latitude. The symbol for Declination is δ. Declination = 0◦ cor- responds to the Celestial Equator, δ = 90◦ corresponds to the North Celestial Pole. Let's look at the Equatorial Coordinates of some objects you should have seen last night. • Arcturus: RA= 14h16m, Dec= +19◦110 (see Appendix A) • Vega: RA= 18h37m, Dec= +38◦470 (see Appendix A) • Venus: RA= 13h02m, Dec= −6◦370 • Saturn: RA= 14h21m, Dec= −11◦410 −! Hand out SC1 charts. Find these objects on them. Now find the constellation of Orion, and read off the Right Ascension and Decli- nation of the middle star in the belt. Next week in lab, you will have the chance to use the computer program Stellar- ium to display the sky and find coordinates of objects (stars, planets). 1.1 Further Remarks on the Equatorial Coordinate System The Equatorial Coordinate System is fundamentally established by the rotation axis of the Earth. -

Positional Astronomy Coordinate Systems

Positional Astronomy Observational Astronomy 2019 Part 2 Prof. S.C. Trager Coordinate systems We need to know where the astronomical objects we want to study are located in order to study them! We need a system (well, many systems!) to describe the positions of astronomical objects. The Celestial Sphere First we need the concept of the celestial sphere. It would be nice if we knew the distance to every object we’re interested in — but we don’t. And it’s actually unnecessary in order to observe them! The Celestial Sphere Instead, we assume that all astronomical sources are infinitely far away and live on the surface of a sphere at infinite distance. This is the celestial sphere. If we define a coordinate system on this sphere, we know where to point! Furthermore, stars (and galaxies) move with respect to each other. The motion normal to the line of sight — i.e., on the celestial sphere — is called proper motion (which we’ll return to shortly) Astronomical coordinate systems A bit of terminology: great circle: a circle on the surface of a sphere intercepting a plane that intersects the origin of the sphere i.e., any circle on the surface of a sphere that divides that sphere into two equal hemispheres Horizon coordinates A natural coordinate system for an Earth- bound observer is the “horizon” or “Alt-Az” coordinate system The great circle of the horizon projected on the celestial sphere is the equator of this system. Horizon coordinates Altitude (or elevation) is the angle from the horizon up to our object — the zenith, the point directly above the observer, is at +90º Horizon coordinates We need another coordinate: define a great circle perpendicular to the equator (horizon) passing through the zenith and, for convenience, due north This line of constant longitude is called a meridian Horizon coordinates The azimuth is the angle measured along the horizon from north towards east to the great circle that intercepts our object (star) and the zenith. -

Exercise 1.0 the CELESTIAL EQUATORIAL COORDINATE

Exercise 1.0 THE CELESTIAL EQUATORIAL COORDINATE SYSTEM Equipment needed: A celestial globe showing positions of bright stars. I. Introduction There are several different ways of representing the appearance of the sky or describing the locations of objects we see in the sky. One way is to imagine that every object in the sky is located on a very large and distant sphere called the celestial sphere . This imaginary sphere has its center at the center of the Earth. Since the radius of the Earth is very small compared to the radius of the celestial sphere, we can imagine that this sphere is also centered on any person or observer standing on the Earth's surface. Every celestial object (e.g., a star or planet) has a definite location in the sky with respect to some arbitrary reference point. Once defined, such a reference point can be used as the origin of a celestial coordinate system. There is an astronomically important point in the sky called the vernal equinox , which astronomers use as the origin of such a celestial coordinate system . The meaning and significance of the vernal equinox will be discussed later. In an analogous way, we represent the surface of the Earth by a globe or sphere. Locations on the geographic sphere are specified by the coordinates called longitude and latitude . The origin for this geographic coordinate system is the point where the Prime Meridian and the Geographic Equator intersect. This is a point located off the coast of west-central Africa. To specify a location on a sphere, the coordinates must be angles, since a sphere has a curved surface. -

Geometric Instruments for the Orientation and Measurement: the Astrolabes

Advances in Historical Studies, 2019, 8, 58-78 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 Geometric Instruments for the Orientation and Measurement: The Astrolabes Barbara Aterini University of Florence, Florence, Italy How to cite this paper: Aterini, B. (2019). Abstract Geometric Instruments for the Orientation and Measurement: The Astrolabes. Ad- The astrolabe, stereographic projection of the celestial sphere on the plane of vances in Historical Studies, 8, 58-78. the equator, simulates the apparent rotation of this sphere around the Earth, https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2019.81004 with respect to a certain latitude, and allows to establish the relative position Received: February 2, 2019 of the stars at a given moment. To understand its meaning and use it is ne- Accepted: March 16, 2019 cessary to recall out the main elements of astronomical geography. From the Published: March 19, 2019 III century BC onwards, various types of astrolabe were built. Among the tools used in the course of the centuries for orientation and measurement, it Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and is the one that perfectly performed both functions, providing measurements Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative related to different fields of investigation: astronomy, chronometry, orienta- Commons Attribution International tion, measurements (length-height-depth), astrology. License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Keywords Open Access Astrolabe, Stereographic Projection, Measuring Instruments, Astronomy 1. Introduction The tools used in the course of the centuries for orientation and measurement are varied, but what fulfilled both functions in a precise manner is certainly the astrolabe. -

Stellarium for Cultural Astronomy Research

RESEARCH The Simulated Sky: Stellarium for Cultural Astronomy Research Georg Zotti Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Susanne M. Hoffmann Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Michael-Stifel-Center/ Institut für Informatik and Physikalisch- Astronomische Fakultät, Jena, Germany [email protected] Alexander Wolf Altai State Pedagogical University, Barnaul, Russia [email protected] Fabien Chéreau Stellarium Labs, Toulouse, France [email protected] Guillaume Chéreau Noctua Software, Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract: For centuries, the rich nocturnal environment of the starry sky could be modelled only by analogue tools such as paper planispheres, atlases, globes and numerical tables. The immer- sive sky simulator of the twentieth century, the optomechanical planetarium, provided new ways for representing and teaching about the sky, but the high construction and running costs meant that they have not become common. However, in recent decades, “desktop planetarium programs” running on personal computers have gained wide attention. Modern incarnations are immensely versatile tools, mostly targeted towards the community of amateur astronomers and for knowledge transfer in transdisciplinary research. Cultural astronomers also value the possibili- ties they give of simulating the skies of past times or other cultures. With this paper, we provide JSA 6.2 (2020) 221–258 ISSN (print) 2055-348X https://doi.org/10.1558/jsa.17822 ISSN (online) 2055-3498 222 Georg Zotti et al. an extended presentation of the open-source project Stellarium, which in the last few years has been enriched with capabilities for cultural astronomy research not found in similar, commercial alternatives. -

ASTR 101L Astronomical Motions I: the Night Sky (Spring)

ASTR 101L Astronomical Motions I: The Night Sky (Spring) Early Greek observers viewed the sky as a transparent sphere which surrounded the Earth. They divided the stars into six categories of brightness and arranged the stars into groupings called constellations (as did many other cultures). Most of the names of the eighty-eight constellations we use today are based on Greek mythology and their Latin translations. Modern astronomy uses the constellation designations to map the sky. On skymaps, the size of the dot is usually related to the brightness of the object (look on your planisphere). Most only show the brightest stars. They are typically named from brightest to faintest using a letter from the Greek alphabet (α, β, γ, etc.) and the constellation name in the genitive form; e.g. alpha (α) Cygni is the brightest star in Cygnus. Many stars also have Arabic names such as Betelgeuse, Algol, and Arcturus; α Cygni is named Deneb and α Ursa Minoris is more commonly known as Polaris. Either designation is correct. In the exercise “Angles and Parallax,” you made a cross-staff and quadrant and learned how to use them to measure objects inside. Now we will use them to measure objects in the night sky, much like Tycho Brahe did in the 1500’s. Remember to record the date, time, and conditions when making any astronomical observations! All numerical data should be recorded to one decimal place. Objectives: . Measure angular separations and altitudes of objects in the night sky with instruments . Estimate angular separations and altitudes of objects in the night sky with your hands .