Current and Emerging Therapeutics of Anxiety and Stress Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novel Neuroprotective Compunds for Use in Parkinson's Disease

Novel neuroprotective compounds for use in Parkinson’s disease A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science By Ahmed Shubbar December, 2013 Thesis written by Ahmed Shubbar B.S., University of Kufa, 2009 M.S., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by ______________________Werner Geldenhuys ____, Chair, Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________,Altaf Darvesh Member, Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________,Richard Carroll Member, Master’s Thesis Committee ___Eric_______________________ Mintz , Director, School of Biomedical Sciences ___Janis_______________________ Crowther , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents List of figures…………………………………………………………………………………..v List of tables……………………………………………………………………………………vi Acknowledgments.…………………………………………………………………………….vii Chapter 1: Introduction ..................................................................................... 1 1.1 Parkinson’s disease .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Monoamine Oxidases ........................................................................................... 3 1.3 Monoamine Oxidase-B structure ........................................................................... 8 1.4 Structural differences between MAO-B and MAO-A .............................................13 1.5 Mechanism of oxidative deamination catalyzed by Monoamine Oxidases ............15 1 .6 Neuroprotective effects -

The Effects of Phenelzine and Other Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor

British Journal of Phammcology (1995) 114. 837-845 B 1995 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0007-1188/95 $9.00 The effects of phenelzine and other monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants on brain and liver 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors Regina Alemany, Gabriel Olmos & 'Jesu's A. Garcia-Sevilla Laboratory of Neuropharmacology, Department of Fundamental Biology and Health Sciences, University of the Balearic Islands, E-07071 Palma de Mallorca, Spain 1 The binding of [3H]-idazoxan in the presence of 106 M (-)-adrenaline was used to quantitate 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver after chronic treatment with various irre- versible and reversible monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors. 2 Chronic treatment (7-14 days) with the irreversible MAO inhibitors, phenelzine (1-20 mg kg-', i.p.), isocarboxazid (10 mg kg-', i.p.), clorgyline (3 mg kg-', i.p.) and tranylcypromine (10mg kg-', i.p.) markedly decreased (21-71%) the density of 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver. In contrast, chronic treatment (7 days) with the reversible MAO-A inhibitors, moclobemide (1 and 10 mg kg-', i.p.) or chlordimeform (10 mg kg-', i.p.) or with the reversible MAO-B inhibitor Ro 16-6491 (1 and 10 mg kg-', i.p.) did not alter the density of 12 imidazoline-preferring receptors in the rat brain and liver; except for the higher dose of Ro 16-6491 which only decreased the density of these putative receptors in the liver (38%). 3 In vitro, phenelzine, clorgyline, 3-phenylpropargylamine, tranylcypromine and chlordimeform dis- placed the binding of [3H]-idazoxan to brain and liver I2 imidazoline-preferring receptors from two distinct binding sites. -

Long-Lasting Analgesic Effect of the Psychedelic Drug Changa: a Case Report

CASE REPORT Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(1), pp. 7–13 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.001 First published online February 12, 2019 Long-lasting analgesic effect of the psychedelic drug changa: A case report GENÍS ONA1* and SEBASTIÁN TRONCOSO2 1Department of Anthropology, Philosophy and Social Work, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain 2Independent Researcher (Received: August 23, 2018; accepted: January 8, 2019) Background and aims: Pain is the most prevalent symptom of a health condition, and it is inappropriately treated in many cases. Here, we present a case report in which we observe a long-lasting analgesic effect produced by changa,a psychedelic drug that contains the psychoactive N,N-dimethyltryptamine and ground seeds of Peganum harmala, which are rich in β-carbolines. Methods: We describe the case and offer a brief review of supportive findings. Results: A long-lasting analgesic effect after the use of changa was reported. Possible analgesic mechanisms are discussed. We suggest that both pharmacological and non-pharmacological factors could be involved. Conclusion: These findings offer preliminary evidence of the analgesic effect of changa, but due to its complex pharmacological actions, involving many neurotransmitter systems, further research is needed in order to establish the specific mechanisms at work. Keywords: analgesic, pain, psychedelic, psychoactive, DMT, β-carboline alkaloids INTRODUCTION effects of ayahuasca usually last between 3 and 5 hr (McKenna & Riba, 2015), but the effects of smoked changa – The treatment of pain is one of the most significant chal- last about 15 30 min (Ott, 1994). lenges in the history of medicine. At present, there are still many challenges that hamper pain’s appropriate treatment, as recently stated by American Pain Society (Gereau et al., CASE DESCRIPTION 2014). -

POISONING with ANTIDEPRESSANTS and DEPRIVATION (1999-2003) • Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

ADMISSION EPISODES TO POISONS TREATMENT POISONING WITH UNIT, CARDIFF 1997 ANTIDEPRESSANTS SIMPLE AND NARCOTIC ANALGESICS 57% HYPNOTICS/ANXIOLYTICS 33% ANTIDEPRESSANTS 22% NEUROLEPTIC DRUGS 7% ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS 6% Philip A Routledge Dept Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Toxicology 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Wales College of Medicine Number of admission episodes Cardiff University WALES, UK WHY ARE ANTIDEPRESSANTS MORTALITY FOR ANTIDEPRESSANT STILL USED? POISONING BY ENGLISH STRATEGIC HEALTH AUTHORITY, 2000-2003 • Depression is common • The morbidity and mortality is high • Non-drug treatments are often unsatisfactory Morgan O et al. Health Statistics Quarterly 2005; 27: 6-12 MORTALITY FOR ANTIDEPRESSANT POISONING POISONING WITH ANTIDEPRESSANTS AND DEPRIVATION (1999-2003) • Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors • Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) • Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) • Others Morgan O et al. Health Statistics Quarterly 2005; 27: 6-12 1 MONOAMINE OXIDASE ENZYMES MONOAMINE OXIDASE (MAOs) INHIBITORS (MAOIs) Dopamine Phenylephrine Tyramine Serotonin (5HT) Norepinephrine Norepinephrine Tyramine • First generation MAOIs Dopamine – Phenelzine (Nardil) Phenylephrine – Tranylcypromine Tyramine – Isocarboxazid MAOI -A MAOI-B • Reversible inhibitors (RIMAs) – Moclobemide (Manerix) MAOI FIRST GENERATION MONOAMINE REVERSIBLE INHIBITORS OF OXIDASE INHIBITORS (MAOIs) RIMA MONOAMINE OXIDASE A (RIMAs) Dopamine Dopamine Phenylephrine Phenylephrine Tyramine Serotonin Serotonin (5HT) (5HT) Norepinephrine Norepinephrine Norepinephrine Norepinephrine -

Package Leaflet: Information for the User Moclobemide 150 Mg Film

Package leaflet: Information for the user Moclobemide 150 mg film-coated tablets Moclobemide 300 mg film-coated tablets Moclobemide Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Moclobemide is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Moclobemide 3. How to take Moclobemide 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Moclobemide 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Moclobemide is and what it is used for Moclobemide film-coated tablets contain the active substance moclobemide. This active substance should make your symptoms better. Moclobemide belongs to a group of medicines known as ‘reversible monoamine oxidase A inhibitors’. These increase the levels of some of the chemical messengers in the brain, for example serotonin and dopamine. This should help to improve your depression (feeling sad, low, worthless or incapable). Medicines which have this effect are called antidepressants. Moclobemide is used to treat major bouts of depression (feeling very low or sad) 2. What you need to know before you take Moclobemide DO NOT take Moclobemide if you are allergic to moclobemide or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6). -

Antidepressants the Old and the New

Antidepressants The Old and The New October, 1998 iii In 1958 researchers discovered that imipramine had antidepressant 1 activity. Since then, a number of antidepressants have been HIGHLIGHTS developed with a variety of pharmacological mechanisms and side effect profiles. All antidepressants show similar efficacy in the treatment of depression when used in adequate dosages. Choosing the most PHARMACOLOGY & CLASSIFICATION appropriate agent depends on specific patient variables, The mechanism of action for antidepressants is not entirely clear; concurrent diseases, concurrent drugs, and cost. however they are known to interfere with neurotransmitters. Non-TCA antidepressants such as the SSRIs have become Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) block the reuptake of both first line agents in the treatment of depression due to their norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5HT). The relative ratio of relative safety and tolerability. Each has its own advantages and their effect on NE versus 5HT varies. The potentiation of NE and disadvantages for consideration in individualizing therapy. 5HT results in changes in the neuroreceptors and is thought to be TCAs may be preferred in patients who do not respond to or the primary mechanism responsible for the antidepressant effect. tolerate other antidepressants, have chronic pain or migraine, or In addition to the effects on NE and 5HT, TCAs also block for whom drug cost is a significant factor. muscarinic, alpha1 adrenergic, and histaminic receptors. The extent of these effects vary with each agent resulting in differing Secondary amine TCAs (desipramine and nortriptyline) have side effect profiles. fewer side effects than tertiary amine TCAs. Maintenance therapy at full therapeutic dosages should be Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) block the 2 considered for patients at high risk for recurrence. -

Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20 Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca Helle Kaasik , Rita C. Z. Souza , Flávia S. Zandonadi , Luís Fernando Tófoli & Alessandra Sussulini To cite this article: Helle Kaasik , Rita C. Z. Souza , Flávia S. Zandonadi , Luís Fernando Tófoli & Alessandra Sussulini (2020): Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 View supplementary material Published online: 08 Sep 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujpd20 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1815911 Chemical Composition of Traditional and Analog Ayahuasca Helle Kaasik a, Rita C. Z. Souzab, Flávia S. Zandonadib, Luís Fernando Tófoli c, and Alessandra Sussulinib aSchool of Theology and Religious Studies; and Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; bLaboratory of Bioanalytics and Integrated Omics (LaBIOmics), Institute of Chemistry, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil; cInterdisciplinary Cooperation for Ayahuasca Research and Outreach (ICARO), School of Medical Sciences, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Traditional ayahuasca can be defined as a brew made from Amazonian vine Banisteriopsis caapi and Received 17 April 2020 Amazonian admixture plants. Ayahuasca is used by indigenous groups in Amazonia, as a sacrament Accepted 6 July 2020 in syncretic Brazilian religions, and in healing and spiritual ceremonies internationally. -

Chapter 151 – Antidepressants

Crack Cast Show Notes – Skin and Soft Tissue Infections www.canadiem.org Chapter 151 – Antidepressants Key Concepts ❏ Although rarely used for depression, MAOIs are used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease ❏ Because serious symptoms can occur after a lengthy latent period, patients with reported MAOI overdose should be admitted for 24 hours, regardless of symptoms. Symptoms are characterized by tachycardia, hypertension, and CNS changes, and later cardiovascular collapse. ❏ The primary manifestations of TCA toxicity are seizures, tachycardia, and intraventricular conduction delay. IV sodium bicarbonate should be administered for QRS prolongation. ❏ DO NOT USE PHYSOSTIGMINE IN TCA OVERDOSE ❏ SSRIs are comparatively benign in overdose. ❏ SNRI ingestions can result in seizures, tachycardia, and occasionally intraventricular conduction delay. ❏ The hallmark feature of serotonin syndrome is lower extremity rigidity (spasticity) with spontaneous or inducible clonus, especially at the ankles. ❏ Serotonin syndrome is primarily treated with supportive care, including discontinuation of the offending agent, and benzodiazepines. Sign Post 1) List 7 pharmacodynamic effects of cyclic antidepressants and describe the physiologic result 2) What are the ECG findings associated with TCA toxicity and what are their implications 3) Describe the management of TCA toxicity 4) What are the diagnostic criteria for Serotonin Syndrome? 5) How can you discern between NMS and Serotonin Syndrome? 6) What are the common meds causing Serotonin Syndrome? 7) Describe the management of Serotonin Syndrome 8) What is the primary risk of toxicity in Bupropion? 9) What are the 3 mechanisms by which MAOI toxicity can occur? And what is the clinical syndrome? 10) List 5 foods and 5 classes of meds that can interact to cause MAOI toxicity 11) Describe the management of MAOI toxicity. -

New Zealand Data Sheet

1 PARNATE tranylcypromine film-coated tablets 10 mg New Zealand Data Sheet 1 PARNATE® (10 MG FILM-COATED TABLETS) PARNATE 10 mg film-coated tablets. 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Parnate 10 mg film-coated tablets: each tablet contains tranylcypromine sulfate equivalent to 10 mg of tranylcypromine. Excipients with known effect: each tablet contains sucrose 6 mg. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Parnate 10 mg film-coated tablets contain "geranium rose" coloured, biconvex, film-coated tablets. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Parnate is indicated for the treatment of symptoms of depressive illness especially where treatment with other types of anti-depressants has failed. It is not recommended for use in mild depressive states resulting from temporary situational difficulties. 4.2 Dose and method of administration Adults Begin with 20 mg a day given as 10 mg in the morning and 10 mg in the afternoon. If there is no satisfactory response after two weeks, add one more tablet at midday. Continue this dosage for at least a week. A dosage of 3 tablets a day should only be exceeded with caution. When a satisfactory response is established, dosage may be reduced to a maintenance level. Some patients will be maintained on 20 mg per day, some will need only 10 mg daily. If no improvement occurs, continued administration is unlikely to be beneficial. 1 2 PARNATE tranylcypromine film-coated tablets 10 mg When given together with a tranquilliser, the dosage of Parnate is not affected. When the medicine is given concurrently with electroconvulsive therapy, the recommended dosage is 10 mg twice a day during the series and 10 mg a day afterwards as maintenance therapy. -

Serotonin Syndrome): Warning of Potential for Fatalities If Combined with Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitors

1 PsychoTropical Commentaries (2018):6;22-32 1 New data on Metaxalone (Skelaxin) and serotonin toxicity (serotonin syndrome): warning of potential for fatalities if combined with serotonin re-uptake inhibitors Gillman, P. K. PsychoTropical Research, Bucasia, Queensland, Australia Abstract Evidence has emerged that Metaxalone (Skelaxin) is a weak monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) which when used in large doses may be sufficiently potent to induce serotonin toxicity (ST) (aka Serotonin Syndrome), but only if and when it is combined with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI). Metaxalone was introduced just over 50 years ago and is used widely for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. It was approved in the days when less extensive pharmacological data concerning drugs existed. Now, theoretical computational (in silico) techniques allow a degree of useful prediction of the likely receptor and enzyme targets of drugs (this in silico modelling has indicated metaxalone is likely to be a weak MAOI — see below). Also, it is an ‘oxazolidinone’, structurally and pharmacologically related to antibiotics like linezolid, which definitely do exhibit both MAOI potency, and also the clinical effect of inducing ST. That strongly suggests the wisdom of vigilance concerning the probability of ST with metaxalone. As of June of 2018 several case reports have described what is probably severe ST in patients who have received metaxalone in combination with an SRI. The fact that such reports have only recently emerged may, at least partly, reflect the increasing knowledge and understanding of ST. The importance of such understanding has been highlighted recently by various incorrect and misleading warnings emanating from several drug regulatory agencies (WHO, FDA etc.) concerning ST, as well as continuing publication of ‘reviews’ which do not reflect current expert knowledge of those drug interactions that are capable of precipitating ST: a recent egregious example being the review by Werneke et al. -

Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidase Activity by Antidepressants and Mood Stabilizers

Biogenic Amines Vol. 25, issue 1 (2011), pp. 59–81 BIA250111A02 Inhibition of monoamine oxidase activity by antidepressants and mood stabilizers Reprinted from: Neuroendocrinology Letters 2010; 31(5): 645–656. Zdeněk Fišar, Jana Hroudová, Jiří Raboch Department of Psychiatry, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague and General University Hospital in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic. Key words: antidepressive agents; monoamine oxidase inhibitors; mood stabilizers Abstract Monoamine oxidase (MAO), the enzyme responsible for metabolism of mono- amine neurotransmitters, has an important role in the brain development and function, and MAO inhibitors have a range of potential therapeutic uses. We investigated systematically in vitro effects of pharmacologically different antide- pressants and mood stabilizers on MAO activity. Effects of drugs on the activity of MAO were measured in crude mitochondrial fraction isolated from cortex of pig brain, when radiolabeled serotonin (for MAO-A) or phenylethylamine (for MAO-B) was used as substrate. The several antidepressants and mood stabilizers were compared with effects of well known MAO inhibitors such as moclobemide, iproniazid, pargyline, and clorgyline. In general, the effect of tested drugs was found to be inhibitory. The half maximal inhibitory concentration, parameters of enzyme kinetic, and mechanism of inhibi- tion were determined. MAO-A was inhibited by the following drugs: pargyline > clorgyline > iproniazid > fluoxetine > desipramine > amitriptyline > imipramine > citalopram > venlafaxine > reboxetine > olanzapine > mirtazapine > tianeptine > moclobemide, cocaine >> lithium, valproate. MAO-B was inhibited by the following drugs: pargyline > clorgyline > iproniazid > fluoxetine > venlafaxine > amitriptyline > olanzapine > citalopram > desipramine > reboxetine > imipramine > tianeptine > mirtazapine, cocaine >> moclobemide, lithium, valproate. The mechanism of inhibition of MAOs by several antidepressants was found various. -

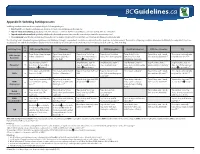

Appendix D: Switching Antidepressants Switching Antidepressants Can Be Accomplished by the Following Strategies: 1

Appendix D: Switching Antidepressants Switching antidepressants can be accomplished by the following strategies: 1. Direct switch: stop the first antidepressant abruptly and start new antidepressant the next day. 2. Taper & switch immediately: gradually taper the first antidepressant, then start the new antidepressant immediately after discontinuation. 3. Taper & switch after a washout: gradually withdraw the first antidepressant, then start the new antidepressant after a washout period. 4. Cross-tapering: taper the first antidepressant (usually over 1-2 week or longer), and build up the dose of the new antidepressant simultaneously. The following table is intended for general guidance only. Whichever strategy is used, patients should be closely monitored for symptoms and adverse events. The duration of tapering should be determined individually for each patient. Physicians should balance the risk of discontinuation symptoms versus risk of delay in new treatment. The washout period is mostly dependent on the t1/2 of the first drug. To Switching From ➞ SSRIs (except fluoxetine) Fluoxetine SNRIs NDRI (bupropion) NaSSA (mirtazapine) RIMA (moclobemide) TCA Taper & stop, then start new Taper & stop, then start Taper & stop5 (or to low Taper & stop5 (or to low Taper & stop5 (or to Taper & stop, wait 1 week, Cross-taper cautiously with SSRIs (except ➞ SSRI at a low dose1,† fluoxetine at low dose dose),1 then start low dose dose),2 then start bupropion. low dose),1 then start then start moclobemide.1,5 very low dose TCA.1,3,5,‡,§ fluoxetine) (10 mg daily)1,† SNRI & very slowly.1,3,5,† mirtazapine cautiously. Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 5 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Fluoxetine* ➞ days.