I Walked with a Zombie: Colonialism and Intertextuality*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Papers of Val Lewton [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2233/papers-of-val-lewton-finding-aid-library-of-congress-82233.webp)

Papers of Val Lewton [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Val Lewton A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Mary A. Lacy Revised by Mary A. Lacy with the assistance of Michael W. Giese Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2004 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004005 Latest revision: 2004-07-01 Collection Summary Title: Papers of Val Lewton Span Dates: 1924-1982 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1926-1951) ID No.: MSS81531 Creator: Lewton, Val Extent: 90 items; 3 containers plus 4 oversize; 6.2 linear feet; 5 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Motion picture producer, screenwriter, and novelist. Correspondence, film scripts, scrapbooks, and other papers pertaining chiefly to Lewton's career as a publicity writer and as a story editor for David O. Selznick at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1928-1942); as scriptwriter and producer of Cat People and other horror films for RKO Radio Pictures (1942-1947); and as novelist, especially as author of No Bed of Her Own (1932). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Names: Lewton, Val Selznick, David O., 1902-1965 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer RKO Radio Pictures, inc. Lewton, Val. No bed of her own (1932) Subjects: Cat people (Motion picture) Horror films Motion picture industry--United States Publicity Occupations: Motion picture producers and directors Novelists Screenwriters Administrative Information Provenance: The papers of Val Lewton, motion picture producer, screenwriter, and novelist, were given to the Library of Congress by his son, Val Edwin Lewton, in 1992. -

Bodies Without Borders: Body Horror As Political Resistance in Classical

Bodies without Borders: Body Horror as Political Resistance in Classical Hollywood Cinema By Kevin Chabot A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2013 Kevin Chabot Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94622-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94622-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

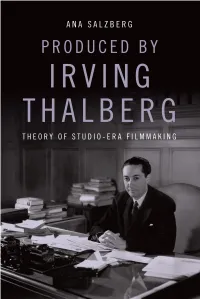

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

The Tragedy of 3D Cinema

Film History, Volume 16, pp. 208–215, 2004. Copyright © John Libbey Publishing ISSN: 0892-2160. Printed in United States of America The tragedy of 3-D cinema The tragedy of 3-D cinema Rick Mitchell lmost overlooked in the bicoastal celebrations The reason most commonly given was that of the 50th anniversary of the introduction of audiences hated to wear the glasses, a necessity for ACinemaScope and the West Coast revivals of 3-D viewing by most large groups. A little research Cinerama was the third technological up- reveals that this was not totally true. According to heaval that occurred fifty years ago, the first serious articles that appeared in exhibitor magazines in attempt to add real depth to the pallet of narrative 1953, most of the objections to the glasses stemmed techniques available to filmmakers. from the initial use of cheap cardboard ones that Such attempts go back to 1915. Most used the were hard to keep on and hurt the bridge of the nose. anaglyph system, in which one eye view was dyed or Audiences were more receptive to plastic rim projected through red or orange filters and the other glasses that were like traditional eyeglasses. (The through green or blue, with the results viewed cardboard glasses are still used for anaglyph pres- through glasses with corresponding colour filters. entations.) The views were not totally discrete but depending on Another problem cited at the time and usually the quality of the filters and the original photography, blamed on the glasses was actually poor projection. this system could be quite effective. -

'The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen Upon Us'

‘The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen upon Us’. The Representation of Gender in Zombie Films, 1968-2013 Leon van Amsterdam Student number: s1141627 Leiden University MA History: Cities, Migration and Global Interdependence Thesis supervisor: Marion Pluskota 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Theory ................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 9 Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 Method ............................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: A history of the zombie and its cultural significance ............................................. 18 Race and gender representations in early zombie films .................................................. 18 The sci-fi zombie and Romero’s ghoulish zombie ............................................................ 22 The loss and return of social anxiety in the zombie genre .............................................. 26 Chapter 3: (Post)feminism in American politics and films ....................................................... 30 Protofeminism ................................................................................................................. -

Heidegger, the Uncanny, and Jacques Tourneur's Horror Films

Heidegger, the Uncanny, and Jacques Tourneur’s Horror Films Curtis Bowman Most horror films are not very horrifying, and many of them are not especially frightening. This is true, of course, of the bad or mediocre productions that populate the genre. Since the failure rate among horror films is very high, it should come as no surprise that we frequently remain unmoved by what we see on the screen. But if we are honest about our reactions, then we must admit that even some of the classics neither horrify nor frighten us. They must have acquired their classic status by moving us in some significant way, but how they managed to do so is not always obvious. We need an explanation of the fact that some of the most successful horror films fail to move us as the genre seems to dictate they should. After all, we typically think that horror films are supposed to horrify and, by implication, to frighten us.1 Excessive familiarity with some films tends to deaden our response. However much we might admire the original Frankenstein (1931), it is difficult for us to be horrified or frightened by it any longer. We respond favorably to the production values, director James Whale’s magnificent visual sense, Boris Karloff’s performance as the monster, and so forth. The film no longer horrifies or frightens us, yet we still consider it a successful horror movie, and thus not merely of historical interest for fans and admirers of the genre. We can still be moved by it in ways that depend on its possessing the features that we expect to find in a horror film. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR in FILM

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Dr. Patrick Warfield, Musicology The horror film soundtrack is a complex web of narratological, ethnographic, and semiological factors all related to the social tensions intimated by a film. This study examines four major periods in the zombie’s film career—the Voodoo zombie of the 1930s and 1940s, the invasion narratives of the late 1960s, the post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s, and the modern post-9/11 zombie—to track how certain musical sounds and styles are indexed with the content of zombie films. Two main musical threads link the individual films’ characterization of the zombie and the setting: Othering via different types of musical exoticism, and the use of sonic excess to pronounce sociophobic themes. COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Patrick Warfield, Chair Professor Richard King Professor John Lawrence Witzleben ©Copyright by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez 2014 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 Introduction 1 Why Zombies? 2 Zombie Taxonomy 6 Literature Review 8 Film Music Scholarship 8 Horror Film Music Scholarship -

Probablemente El Diablo: El Terror Elíptico De La Séptima Víctima

PROBABLEMENTE EL DIABLO: EL TERROR ELÍPTICO DE LA SÉPTIMA VÍCTIMA Francisco García Gómez Universidad de Málaga RESUMEN La séptima víctima, la primera película dirigida por Mark Robson, constituye un magnífico ejemplo de la concepción del terror que tenía el productor Val Lewton. Su cuarto filme para la RKO, el primero no dirigido por Jacques Tourneur, pone de manifiesto que Lewton era el auténtico responsable de su ciclo fantástico. PALABRAS CLAVE: RKO, Val Lewton, Mark Robson, serie B, terror, satanismo, paladismo. ABSTRACT «Probably the Devil: The Elliptical Terror in The Seventh Victim». The Seventh Victim, first film directed by Mark Robson, is a magnificent example of the producer Val Lewton’s terror concept. His fourth RKO film, the first without Jacques Tourneur, reveals that Lewton was the genuine responsible of his fantastic cycle. KEY WORDS : RKO, Val Lewton, Mark Robson, B Film, terror, satanism, paladism. 163 Una película a redescubrir y reivindicar, ése es el caso de La séptima víctima (The Seventh Victim, 1943), la cuarta del ciclo de nueve cintas de terror de serie B producidas por Val Lewton en la RKO entre 1942 y 19461. Dirigida por Mark Robson en su debut como realizador, fue además la primera cuya dirección no corrió a cargo de Jacques Tourneur, tras La mujer pantera (Cat People, 1942), Yo anduve con un zombi (I Walked with a Zombie, 1943) y El hombre leopardo (The Leopard Man, 1943). Precisamente a consecuencia de los grandes éxitos de público obtenidos con estas tres, el estudio decidió separar al tándem Lewton-Tourneur, convencido de que rendirían el doble por separado, poniendo en seguida al francés al frente de mayores presupuestos. -

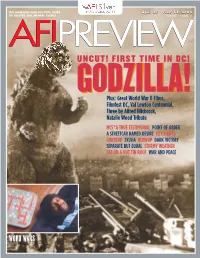

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

The Emergence and Development of the Sentient Zombie: Zombie

The Emergence and Development of the Sentient Zombie: Zombie Monstrosity in Postmodern and Posthuman Gothic Kelly Gardner Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Literature and Languages University of Stirling 31st October 2015 1 Abstract “If you’ve never woken up from a car accident to discover that your wife is dead and you’re an animated rotting corpse, then you probably won’t understand.” (S. G. Browne, Breathers: A Zombie’s Lament) The zombie narrative has seen an increasing trend towards the emergence of a zombie sentience. The intention of this thesis is to examine the cultural framework that has informed the contemporary figure of the zombie, with specific attention directed towards the role of the thinking, conscious or sentient zombie. This examination will include an exploration of the zombie’s folkloric origin, prior to the naming of the figure in 1819, as well as the Haitian appropriation and reproduction of the figure as a representation of Haitian identity. The destructive nature of the zombie, this thesis argues, sees itself intrinsically linked to the notion of apocalypse; however, through a consideration of Frank Kermode’s A Sense of an Ending, the second chapter of this thesis will propose that the zombie need not represent an apocalypse that brings devastation upon humanity, but rather one that functions to alter perceptions of ‘humanity’ itself. The third chapter of this thesis explores the use of the term “braaaaiiinnss” as the epitomised zombie voice in the figure’s development as an effective threat within zombie-themed videogames. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing