Intellectual Property in Transition Economies: Assessing the Latvian Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATVIA in REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30

LATVIA IN REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30 CONTENTS Government Latvia's Civic Union and New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party About 1,700 people Have Expressed Wish to Join Latvia's Newly-Founded ZRP Party President Bērziņš to Draft Legislation Defining Criteria for Selection of Ministers Parties Represented in Current Parliament Promise Clarity about Candidates This Week Procedure Established for President’s Convening of Saeima Meetings Economics Bank of Latvia Economist: Retail Posts a Rapid Rise in June Latvian Unemployment Down to 12.3% Fourteen Latvian Banks Report Growth of Deposits in First Half of 2011 European Commission Approves Cohesion Fund Development Project for Rīga Airport Private Investments Could Help in Developing Rīga and Jūrmala as Tourist Destinations Foreign Affairs Latvian State Secretary Participates in Informal Meeting of Ministers for European Affairs Cabinet Approves Latvia’s Initial Negotiating Position Over EU 2014-2020 Multiannual Budget President Bērziņš Presents Letters of Accreditation to New Latvian Ambassador to Spain Society Ministry of Culture Announces Idea Competition for New Creative Quarter in Rīga Unique Exhibit of Sand Sculptures Continues on AB Dambis in Rīga Rīga’s 810 Anniversary to Be Celebrated in August with Events Throughout the Latvian Capital Labadaba 2011 Festival, in the Līgatne District, Showcases the Best of Latvian Music Latvian National Opera Features Special Summer Calendar of Performances in August Articles of Interest Economist: “Same Old Saeima?” Financial Times: “Crucial Times for Investors in Latvia” L’Express: “La Lettonie lutte difficilement contre la corruption” Economist: “Two Just Men: Two Sober Men Try to Calm Latvia’s Febrile Politics” Dezeen magazine: “House in Mārupe by Open AD” Government Latvia's Civic Union, New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party At a party congress on July 30, Latvia's Civic Union party voted to participate in the foundation of the Unity party, Civic Union reported in a statement on its website. -

Worldnewmusic Magazine

WORLDNEWMUSIC MAGAZINE ISCM During a Year of Pandemic Contents Editor’s Note………………………………………………………………………………5 An ISCM Timeline for 2020 (with a note from ISCM President Glenda Keam)……………………………..……….…6 Anna Veismane: Music life in Latvia 2020 March – December………………………………………….…10 Álvaro Gallegos: Pandemic-Pandemonium – New music in Chile during a perfect storm……………….....14 Anni Heino: Tucked away, locked away – Australia under Covid-19……………..……………….….18 Frank J. Oteri: Music During Quarantine in the United States….………………….………………….…22 Javier Hagen: The corona crisis from the perspective of a freelance musician in Switzerland………....29 In Memoriam (2019-2020)……………………………………….……………………....34 Paco Yáñez: Rethinking Composing in the Time of Coronavirus……………………………………..42 Hong Kong Contemporary Music Festival 2020: Asian Delights………………………..45 Glenda Keam: John Davis Leaves the Australian Music Centre after 32 years………………………….52 Irina Hasnaş: Introducing the ISCM Virtual Collaborative Series …………..………………………….54 World New Music Magazine, edition 2020 Vol. No. 30 “ISCM During a Year of Pandemic” Publisher: International Society for Contemporary Music Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik / Société internationale pour la musique contemporaine / 国际现代音乐协会 / Sociedad Internacional de Música Contemporánea / الجمعية الدولية للموسيقى المعاصرة / Международное общество современной музыки Mailing address: Stiftgasse 29 1070 Wien Austria Email: [email protected] www.iscm.org ISCM Executive Committee: Glenda Keam, President Frank J Oteri, Vice-President Ol’ga Smetanová, -

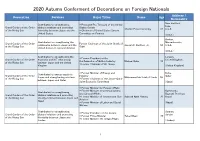

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals Address / Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age Nationality New Hartford, Contributed to strengthening * President Pro Tempore of the United Iowa, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting States Senate Charles Ernest Grassley 87 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun friendship between Japan and the * Chairman of United States Senate United States Committee on Finance (U.S.A.) Boston, Contributed to strengthening the Massachusetts, Grand Cordon of the Order Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of relationship between Japan and the Joseph F. Dunford Jr. 64 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun Staff United States on national defense (U.S.A.) Contributed to strengthening the London, * Former President of the Grand Cordon of the Order economic and ICT relationship United Kingdom Confederation of British Industry Michael Rake 72 of the Rising Sun between Japan and the United * Former Chairman of BT Group Kingdom (United Kingdom) * Former Minister of Energy and Doha, Contributed to energy supply to Grand Cordon of the Order Industry Qatar Japan and strengthening relations Mohammed bin Saleh Al Sada 59 of the Rising Sun * Former Chairman of the Japan-Qatar between Japan and Qatar Joint Economic Committee (Qatar) * Former Minister for Foreign Affairs * Former Minister of Communications Kathmandu, Contributed to strengthening and General Affairs Bagmati Province, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting * Former Minister of Tourism and Civil Ramesh Nath Pandey 76 Nepal of -

Dzintari Concert Hall with His Solo Concert and Magnificent Show

JŪRMALA RECOMMENDS Publisher: Jūrmala City Council Print: Corporate Photography: Dzintaru Concert Hall, Ģirts Raģelis, Ivars Ķezbers, Krišjānis Eihmanis, Grilbar “Lighthouse“, Adventure Park “Jūrmalas Tarzāns” Jūrmala recommends Jūrmala recommends INTARS BUSULIS CONCERT “THE NEXT STOP” JUNE 17 TH AND 18TH, 20:00 The program of the concerts has been formed of the best, well known and beloved songs in Latvia and Russia of the last years, as well as songs from the upcoming album of Intars Busulis, that has been recorded here, in Latvia. The authors of music of the songs are Kārlis Lācis and Intars Busulis. The first single of the album – “Miglas rīts” (Morning of mist) became very favoured by the listeners and stayed at the peaks of music tops for several weeks. HUMOUR SHOW “KVARTAL 95” JULY 9 TH, 19:30 Humour is fresh and current, sharp and precise. That is exactly why humourists are sometimes called the antidepressants. The most popular Ukrainian humour- ists after triumphant tour in America and Australia are ready for Latvia. Vladimir Zelyenskiy, Evgeniy Koshevoi, Juriy Krapov and all the rest of the Kvartal`s team with new characters, fresh jokes and topical parodies – everything in one concert and on one stage. SHOW “STAND UP TNT” JULY 24TH, 19:30 All the best comics of the project – Stas Starovoitov, Viktor Komarov, Slava Ko- misarenko, Ruslan Beliy, Julia Ahmedova, Timur Karginov, Nurlan Saburov – will cheer up the guests with funny monologues on everyday situations that we all have experienced. Stand Up comics turn into jokes the problems, which usually spoil one`s mood, that is why in the new solo program of the performers there is even more humour on everything that is important, provocative and characteristic to life. -

Xiami Music Genre 文档

xiami music genre douban 2021 年 02 月 14 日 Contents: 1 目录 3 2 23 3 流行 Pop 25 3.1 1. 国语流行 Mandarin Pop ........................................ 26 3.2 2. 粤语流行 Cantopop .......................................... 26 3.3 3. 欧美流行 Western Pop ........................................ 26 3.4 4. 电音流行 Electropop ......................................... 27 3.5 5. 日本流行 J-Pop ............................................ 27 3.6 6. 韩国流行 K-Pop ............................................ 27 3.7 7. 梦幻流行 Dream Pop ......................................... 28 3.8 8. 流行舞曲 Dance-Pop ......................................... 29 3.9 9. 成人时代 Adult Contemporary .................................... 29 3.10 10. 网络流行 Cyber Hit ......................................... 30 3.11 11. 独立流行 Indie Pop ......................................... 30 3.12 12. 女子团体 Girl Group ......................................... 31 3.13 13. 男孩团体 Boy Band ......................................... 32 3.14 14. 青少年流行 Teen Pop ........................................ 32 3.15 15. 迷幻流行 Psychedelic Pop ...................................... 33 3.16 16. 氛围流行 Ambient Pop ....................................... 33 3.17 17. 阳光流行 Sunshine Pop ....................................... 34 3.18 18. 韩国抒情歌曲 Korean Ballad .................................... 34 3.19 19. 台湾民歌运动 Taiwan Folk Scene .................................. 34 3.20 20. 无伴奏合唱 A cappella ....................................... 36 3.21 21. 噪音流行 Noise Pop ......................................... 37 3.22 22. 都市流行 City Pop ......................................... -

Glendale's Mayor

SEPTEMBER 23, 2017 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVIII, NO. 10, Issue 4504 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Military Hospitals in Nicole Babikian Hajjar Leads Mirror Armenia to Be Merged With Civic Ones 85th Anniversary Gala Benefit YEREVAN (Arka.am) – Military hospitals in Armenia will be integrated with civilian hospitals, WATERTOWN – The Armenian Armenian Defense Minister Vigen Sargsyan said at By Sara Janjigian Trifiro Mirror-Spectator will mark its the 6th Armenia-Diaspora forum that started in 85th anniversary with a two-day Yerevan on September 18. “Military hospitals are celebration including a sympo- often better equipped and have more resources sium titled “Journalism and Fake News: The Armenian Genocide and Karabagh” on than district hospitals. Together with the ministry November 2 at Wellesley College, and a gala benefit under the theme of “Reflecting. of health we will launch a pilot project to merge Connecting. Inspiring” on November 3 at the Boston Marriott Newton. These cele- military and civic hospitals in Sisian, Berd and bratory events will feature an impressive line-up of speakers and honorees, includ- Vardenis,” he said. He said the planned merger will ing internationally acclaimed British journalist Robert Fisk, Middle East corre- allow the army to help ordinary citizens, adding spondent for The Independent and that military hospitals too have problems. One of seven-time recipient of the British Press these problems, he said, is modernization of the Awards’ “Reporter of the Year”; colum- Central Military Clinical Hospital. “We have the nist for Diken and Al Monitor and former best resuscitation and surgical departments. -

The Emigrant Communities of Latvia

IMISCOE Research Series Rita Kaša Inta Mieriņa Editors The Emigrant Communities of Latvia National Identity, Transnational Belonging, and Diaspora Politics IMISCOE Research Series This series is the official book series of IMISCOE, the largest network of excellence on migration and diversity in the world. It comprises publications which present empirical and theoretical research on different aspects of international migration. The authors are all specialists, and the publications a rich source of information for researchers and others involved in international migration studies. The series is published under the editorial supervision of the IMISCOE Editorial Committee which includes leading scholars from all over Europe. The series, which contains more than eighty titles already, is internationally peer reviewed which ensures that the book published in this series continue to present excellent academic standards and scholarly quality. Most of the books are available open access. For information on how to submit a book proposal, please visit: http://www. imiscoe.org/publications/how-to-submit-a-book-proposal. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13502 Rita Kaša • Inta Mieriņa Editors The Emigrant Communities of Latvia National Identity, Transnational Belonging, and Diaspora Politics Editors Rita Kaša Inta Mieriņa Stockholm School of Economics in Riga Institute of Philosophy and Sociology Riga, Latvia University of Latvia Riga, Latvia ISSN 2364-4087 ISSN 2364-4095 (electronic) IMISCOE Research Series ISBN -

From Opposition to Independence: Social Movements in Latvia, 1986- 199 1

FROM OPPOSITION TO INDEPENDENCE: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN LATVIA, 1986-199 1 by Daina Stukuls #569 March 1998 CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON SOCIAL ORGANIZATION WORKING PAPER SERIES The Center for Research on Social Organization is a facility of the Department of Sociology, The University of Michigan. Its primary mission is to support the research of faculty and students in the department's Social Organization graduate program. CRSO Working Papers report current research and reflection by affiliates of the Center To request copies of working papers, or for hrther information about Center activities, write us at 4501 LS&A Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 48109, send e-mail to [email protected], or call (734) 764-7487. Introduction Prior to 1987, independent mass demonstrations in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia, indeed, in the entire Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, were unheard of. Not only were they strictly forbidden by Soviet authorities, but the fear wrought by decades of repression seemed to make oppositional collective action very unlikely. While pockets of resistance and individual dissident efforts dotted the Soviet historical map, the masses were docile, going out on to the streets only in response to compulsory parades and marches designed to commemorate holidays like May Day. In 1986, a policy of greater openness in society, glasnost', was initiated by the new Secretary General of the Communist Party of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev. Among the changes brought about by glasnost' was a greater tolerance by authorities of open expression in society, though this too was limited, as the policy was intended to strengthen rather than weaken the union. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Soundtrack of Stagnation: Paradoxes Within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5jm0m00m Author Grabarchuk, Alexandra Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Soundtrack of Stagnation: Paradoxes within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Alexandra Grabarchuk 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Soundtrack of Stagnation: Paradoxes within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970s by Alexandra Grabarchuk Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor David MacFadyen, Chair The “underground” Soviet rock scene of the 1980s has received considerable scholarly attention, particularly after the fall of the USSR when available channels of information opened up even more than in the glasnost years. Both Russian and American academics have tackled the political implications and historical innovations of perestroika-era groups such as Akvarium, Mashina Vremeni, and DDT. Similarly, the Beatles craze of the 1960s is also frequently mentioned in scholarly works as an enormous social phenomenon in the USSR – academics and critics alike wax poetic about the influence of the Fab Four on the drab daily lives of Soviet citizens. Yet what happened in between these two moments of Soviet musical life? Very little critical work has been done on Soviet popular music of the 1970s, its place in Soviet society, or its relationship to Western influences. -

The Geopolitics of History in Latvian-Russian Relations

The Geopolitics of History in Latvian-Russian Relations Editor Nils Muižnieks Academic Press of the University of Latvia 2011 UDK 327(474.3+70)(091) Ge 563 Reviewed by: Prof. Andrejs Plakans, Ph. D., USA Prof. Juris Rozenvalds, Ph. D., Latvia The preparation and publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Latvia and the Baltisch-Deutsches Hochschulkontor with the support of funding from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Layout: Ilze Reņģe Cover design: Agris Dzilna The photographs on the cover are by Klinta Ločmele, Olga Procevska and Vita Zelče. © University of Latvia, 2011 © Agris Dzilna, cover design, 2011 ISBN 978-9984-45-323-1 Contents Nils Muižnieks. History, Memory and Latvian Foreign Policy ........... 7 Part I: Latvia in Russia’s Historical Narrative Kristīne Doroņenkova. Official Russian Perspectives on the Historical Legacy: A Brief Introduction .................... 21 Vita Zelče. Latvia and the Baltic in Russian Historiography . 31 Solvita Denisa-Liepniece. From Imperial Backwater to Showcase of Socialism: Latvia in Russia’s School Textbooks . 59 Dmitrijs Petrenko. The Interpretation of Latvian History in Russian Documentary Films: The Struggle for Historical Justice ............ 87 Part II: Russian-Latvian Comparisons and “Dialogues” Klinta Ločmele, Olga Procevska, Vita Zelče. Celebrations, Commemorative Dates and Related Rituals: Soviet Experience, its Transformation and Contemporary Victory Day Celebrations in Russia and Latvia ............................... 1 0 9 Ojārs Skudra. Historical Themes and Concepts in the Newspapers Diena and Vesti Segodnya in 2009 ..................... 139 Ivars Ijabs. The Issue of Compensations in Latvian–Russian Relations . 175 Toms Rostoks. Debating 20th Century History in Europe: The European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Compared ............................ -

Juris Podnieks and Latvian Documentary Cinema

FROM THE PERSONAL TO THE PUBLIC: JURIS PODNIEKS AND LATVIAN DOCUMENTARY CINEMA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Maruta Zane Vitols, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor J. Ronald Green, Adviser Professor Lisa Florman _________________________________ Professor Judith Mayne Adviser History of Art Graduate Program Copyright by Maruta Zane Vitols 2008 ABSTRACT In recent decades and particularly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, cinema scholars have devoted a considerable amount of attention to Eastern European films and filmmakers. Yet, the rich film tradition of the Baltic States, particularly the thriving Latvian national cinema, remains foreign to western cinema scholars. One finds very little written in academia in this subject area, although the rapidly growing economies and the increase of the political currency of the Baltic States have sparked a new awareness of this geographical area. A fresh interest in Latvian filmmakers as the voices of their society is emerging, stemming from the country’s rich cinema history. Within the realm of Latvian documentary filmmaking, one figure from recent years shines as a star of the genre. Juris Podnieks (1950-1992) and his films hold a privileged place in Latvian culture and history. His breakthrough feature Is It Easy to Be Young? (1986) heralded the advent of a new era for Latvian and Soviet documentary filmmaking accompanying the implementation of Gorbachev’s glasnost plan in the Soviet Union. Podnieks took advantage of the new policy of openness and employed Is It Easy to Be Young? as a vehicle for exploring the state of youth culture under a non-democratic regime. -

Party Music in Latvia in the 20Th Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems Party Music in Latvia in the 20th Century ĒVALDS DAUGULIS Daugavpils University Anotācija. Ballīšu mūzika Latvijā ir nesaraujami saistīta ar tās vēstures līklo- čiem – kā spogulī te varam ieraudzīt visu sarežģīto un neviennozīmīgo 20. ga- dsimta gaitu. Tā mainījās laika gaitā, bet nemainījās savā būtībā: vienkāršībā un pieejamībā. Arī deju mūzikā parādījās viens no svarīgākiem mūzikas ra- dīšanas principiem un mehānismiem, kas aktuāls arī šobaltdien: pārņemt no akadēmiskās mūzikas stilistiskos modeļus, paņēmienus un izteiksmes līdzekļus un pārcelt tos citā vidē. Ballīšu mūzika Latvijā 20. gadsimta I pusē laukos un pilsētā. Repertuārs, instrumentārijs, stils, funkcionālā piesaiste. Deju mūzikas karaļi Alfrēds Vinters, brāļi Laivinieki, par tango karali dēvētais Oskars Stroks u.c. Būtiskas pārmaiņas deju mūzikā pēc Otrā pasaules kara. Atslēgas vārdi: ballīšu mūzika, evolūcija, instrumentārijs, repertuārs. Abstract. Party music in Latvia can hardly be considered separately from the turns and twists of its history – as a mirror it reflects the whole intricate and complicated course of the 20th century. The music changed in the course of time, but it did not change in its essence, namely, its simplicity and availability. Party music experienced the appearance of one of the most significant princi- ples and mechanisms of composing, which is topical up to date: to take over the stylistic models, techniques and means of expression of academic music and adapt them to a different environment. Party music in the 1st part of the 20th century in Latvian towns and countryside.