By Jjfi.2M ¿¿¿ ?... Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1935 Brown and Gold Vol 17 No 09 February 15, 1935

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 2-15-1935 1935 Brown and Gold Vol 17 No 09 February 15, 1935 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons Recommended Citation "1935 Brown and Gold Vol 17 No 09 February 15, 1935" (1935). Brown and Gold. 100. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/100 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Classes ---·-·,Dispose of Washington's Play Tickets Birthday GO liD Early! ! --- Vol. XVII, No. 9 REGISOOLLEG~DENVER, COLORADO February 15, 1935 PRESS CONVENTION BECKONS REGIS COLLEGIANS Father Herbers Spirit and ·Youthful Zest Reviews "The I DEBATING CLUB Loretto Heights Plans Large First Legion" IS ORGANIZED State Gathering; Noted Mark Sophomore Dance One of the most brilliant Catho lic plays of the year, "The First A. Andrew Hauk was elected • Legion," was reviewed by the Rev. president of the debating club on Lecturers to Speak •al mosphere at his table quite informal Joseph A. Herbers, S.J., president Feb. 13. Fred Close is vice-presi and was ably abetted by that bit College Socl of the College in the auditorium of dent and James Loughlin, secretary. of blond boisterousness, recruited Saint Joseph's Hospital last Mon- Alec Keller is in charge of arrange- Symposia and Round Table Discussions Will .W e II Atten de d from Pancretia Hall. -

Notre Dame Catholic Parish Central Office: 5100 W

Notre Dame Catholic Parish Central Office: 5100 W. Evans Ave., Denver, CO 80219 303-935-3900 Church: 2190 S. Sheridan Blvd. www.denvernotredame.org School: 2165 S. Zenobia St., Denver, CO 80219 www.notredamedenver.org September 5/6, 2020; 23rd Sunday in Ordinary “Owe no one anything, except to love one another; for he who loves his neighbor has fulfilled the law.” Romans 12: 8 Relationships: Self-assessment; Honesty; Truth; Justice; Kindness “… where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” Matthew 18: 20 The Mission of Notre Dame Parish is: To Make Disciples of Jesus Christ. Behold, I make (Matthew 28:19) all things new. Notre Dame Catholic Parish is a devout community, faithful to Christ and his Church, 2019/2020 Notre Dame that builds up his kingdom through Parish Pastoral Theme evangelization, education, and communication. 23rd Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5/6, 2020 Readings for September 6 - 13 Pastoral Services Sunday, September 6 1st Ezekiel 33: 7-9 Baptism for Baptism Preparation Sessions are held on the first 23rd Sunday in children 6 Wednesday of each month at 7:00pm in the Ministry Ordinary Time 2nd Romans 13: 8-10 years and Center. To make arrangements to attend the class and under have your child baptized, please contact Jim at Gospel Matthew 18: 15-20 [email protected] or 303-742-2351. Monday, September 7 1st 1 Corinthians 5: 1-8 Baptism for Contact Jim at [email protected] or call Gospel Luke 6: 6-11 children 7 him at 303-742-2351. -

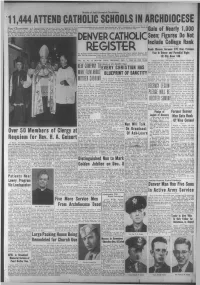

11,444 Anend CATHOLIC SCHOOLS in ARCHOIOCESE REGISTER

' 'Member of Audit Bureau of Cireulotlena 11,444 AnEND CATHOLIC SCHOOLS IN ARCHOIOCESE Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc, 1944 — Permission to Reproduce, Except on C •** Si, Francis de Sales’ high school in Denver were blessed by the MosI 1.^ C 'lV V^At4-oAI U U IIA o Bev. Archbishop Urban J. Velir, pictured below with Monsignor Charles Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M.' Friday Following Issue Hagus (left) and the Rev, Gregory Smith, pastor (right), on Dec. 4. Forty-one priests^ from the Gain of Nearly 1,000 city’s parishes attended the rile and were guests at a dinner served in the school’a new cafeteria at noon. The Rev. Robert McMahon, assistant pastor, is in the rear of the Archbishop at the left. Talks were given by the Archbishop, Father .Smith, the Rev.Hubert Newell, and Ronald Donovan, a student. D E N V E R C A T H O L I C S een; Figures Do Not Include College Rank REGISTER Grade Classes Increase 375 Over Previous The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Year In Denver and Parochial Highs Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mafl), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features^ and Wide World Photos. Of Gily Grow 146 VOL. XL. No. 14. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, DEC. 7, 1944. tl PER YEAR A gain of nearly 1,000 pupils in the Catholic schools of the Archdiocese of Denver is recorded in the enrollment Church of Air Speaker Says report of the first semest'er of the current scholastic year by the Rev. -

Jubilee Drive Definitely Going Over Top Denver Catholic

National Circulation Over 470,000; Denver Catholic Register, 21^49 JUBILEE DRIVE DEFINITELY GOING OVER TOP + + + + + + Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1940— Permission to Reproduce, Excepting on Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue in •i>* clergy procession preceding.the Solemn Pontifical Oll'Vti »/M.C/ll'tl'T o l> Mggg g( life Cathedral Wednesday, May 29, is shown below. Reading from left to right, front row, are the Rt. Rev, Hugh L. McMenamin, the Very Rev. Magnificent Affair Charles Hagus, the Very Rev. Thomas D. Coyne, GM ., and the Rt. Rev. Matthew Smith; second row, the Very Rev. William Higgins, the Very Rev. Robert Kelley, S.J.; Bishop Urban J. Vehr, the Very Rev. Harold V. Campbell, and the Rt. Rev. Abbot Leonard Schwinn, O.S.B. After the Mass a delegation o f students led by Eva Sydney Monaghan o f lx>retto Heights college pre Marks Anniversary sented the Bishop with a spiritual' bouquet and a check for |1,S00 (lower photo). Bishop Vehr an DENVER CATHOLIC nounced that the money would form the beginning o f a school children’s burse for the seminary. Shown in the picture are (left to right): First row— Monsignor J. J. Bosetti, V.G.; Eva Sydney Monaghan, Bishop Vehr,-Father Hubert Newell, diocesan superintendent of schools, and Kathleen McCormick; sec ond row— James Wilson, Florence Piute, Bernard Deidel, Dorothy Pantoski, and Daniel Foley. Of Denver Dishop REGISTER $120,051 on Hand or Pledged; More Parishes The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. -

1949-1950 Regis College Bulletin

REGIS COLLEGE BULL~TIN 1949-1950 DENVER 11, COLORADO INDEX A.B. Degree . 32, 33, 34 Glee Club and Orchestra .. 18 Academic Year ... .. ...... ... 28 Grading System .. 29 Accounting .....................42 Greek ............. 5I Administration Officers .... 6 Health Service . 24 Advanced Standing .. 26, 27 Historical Sketch .. • ...... 15 Attendance . .. 28 History 72 B.S. Degree ... 32, 34, 35, 36 Honors ...... ............ .l3 Biology . ... 60 Honors Courses 33 Biology Club ...... .......... .. 19 Jesuit Colleges .. ············· .. 81 Board of Trustees ............... 6 Laboratories . ··········· . 17 Buildings .. ...... ....... ... ...... 17 Latin ..... 5I Business Administration 45 Library .. 17 Calendar ........ ....................... 4 Literature Club . 20 Chapel Exercises ................... 20 Location ... 15 32 Chemistry .............. ......... 62 MaJOr, Concentration Mathematics . .. 65 Chemistry Club ......... .......... 18 Membership in Educational Classification of Students....... 29 Associations .. 16 Committees .............. ........... 6 Objectives, Statement of .. .. 15 Courses of Instruction......... 41 Organiz.ations .. 17·20 Credit Points ...... ......... ..... 29 Philosophy .. 75 Degrees Conferred 82, 83 Physical Education ..... 77 Degree Requirements ...... 32, 33 Physics 68 Delta Sigma .......................... 18 Pre-Dentistry, Minimum 38 Discipline ............................. 20 Pre-Law, Minimum 39 Dismissal ............................. 30 Pre-Medicine, Minimum 39, 40 Division of Language Prites, Awards -

Enew Al 34 National Convention

^ ^ e n e w a l NATIONAL 34 national COUNCILof CATHOLIC convention WOMEN ^ » i t y s ^ » 4 Archbishop’s Welcome Archbishop’s House 1536 Logan Street Denver, Colorado 80203 As Archbishop of Denver I extend my warmest welcome and that of our people to all of you Catholic Women who are assembling in our Mile High City for your National Convention. Many of you have traveled great distances at no small personal sacrifice and it is my hope that you will return to your homes exhilarated not only with the majesty of the Rockies, but more especially with the sense of accomplishment and direction to be derived from your partici pation in and carrying out of your Convention theme — 'The Parish: Renewal in Progress.” At no time has the Church been in greater need of the contribution to be made by truly Christian laywomen, who are willing not only to live life, but to renew and refresh it. To be fearful of renewal and change is to be fearful of life itself. May this renewal teach each of you to live not for yourselves, but according to the demands of the new law of charity, to adminis ter this grace you have received to others. Devotedly yours in Christ, Archbishop of Denveriver^/ Archbishop James V. Casey In Recognition: Hosts of NCCW Convention RECEPTION DENVER ARCHDIOCESAN COUNCIL OF Family Affairs Mrs. John Hinterreiter Mrs. Norman Patrick Community Affairs Mrs. Joseph Medina CATHOLIC WOMEN 1968-69 Mrs. Joseph Waters International Affairs Mrs. John E. DeMers Mrs. Albert Seep Spiritual Director Reverend Robert V. -

Work of Bishop in Into Lifo of Worid Bringing Christ Told in Sermon

special Consecration Section THE DENVER CATHOLIC REGISTER Thursday, Sept. 25, 1946 Page One Work of Bishop in Bringing Christ Into Lifo of Worid Told in Sermon APOSTOLIC SUCCESSION AND POWERS Principals in Service Shown OF HIERARCHY MASTERFULLY OUTLINED BY ORDINARY OF SALT UKE DIOCESE Following is the full text of the sermon delivered by the Most Rev. Duane G. Hunt, D.D., Bishop of Salt Lake, Wednesday, Sept. 24, in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Denver, at the consecration of the Most Rev. Hubert Michael Newell, D.D., as Coadjutor Bishop of the Diocese of Cheyenne. “ And behold, I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world.”—Matt, xxviii, 20. ' The grace of God’s friendship, the highest of all His gifts, has been offered to man in all ages of human existence. It has been fhanifested in many ways; in pat;ernal guidance, in benevolent protection, in redeeming from sin, and in the daily outpouring of mercy and love. This friendship has unfolded itself in a progressive pattern, advancing from distant to close intimacy, until we of today are blessed by its final measure of completeness. The first period of God’s relationship with man includes all the time before the coming of Cur Divine Lord. Limiting attention to the chosen people, to those who had the true faith, we note that even with them there was little close intimacy with God. He was a remote being, far away in heaven, looking down upon His people. Being a pure spirit. He was beyond the power of man to see and touch, He was spoken about only in hushed terms of reverence and fear. -

1946 Brown and Gold Vol 28 No 3 April, 1946

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 4-1-1946 1946 Brown and Gold Vol 28 No 3 April, 1946 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1946 Brown and Gold Vol 28 No 3 April, 1946" (1946). Brown and Gold. 237. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/237 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CipAiL 1946 REGIS BAZAAR REGIS GROUNDS- 52.ad and l.owell Bouleval'd MAY 1-3-4, 1946 TO BE GIVEN AWAY MAY 4 1946 DEI.UXE DE SOTO 2.-DOOB SEDAN Bam Dinael'- Thul'sday Night, May 4 Eal a Good Breaklasl REGIS VETS For your health's sake, get up five minutes earlier every morning, and eat a good break· fast-you need that energy, after your SPRING night's fast. You' ll do better class work, and better studying after a good breakfast of FROLIC fruit, cere a I, toast, eggs, and the like. • Moy 10, 1946 LAKEWOOD Country Club KE. 6297 B 0 R AN 1527 CLEVELAND PL. liND SONS CRAPE I. The BROWN and G -OLD Dedicated to the spirit of Regis, which unfailingly guides those who have departed from her venerable halls, wherever they may go--to the field of battle, to the office desk, to the law court, or to the altar. -

History of Saint Joseph Parish

HISTORYHISTORY OFOF SAINTSAINT JOSEPHJOSEPH PARISHPARISH 1 Acknowledgement This accounting gives enormous credit to Father Robert Reycraft for his thorough research in 1975 in documenting the early history of Fort Collins and the first 100 years of St. Joseph Parish. The parish is most grateful for his rich and personal chronicle of the early pioneers, missionaries and priests who shaped our area and place of worship. Many thanks to the Archdiocese of Denver and the Fort Collins Library for making available the records and documents used in researching this history. The parish owes a debt of gratitude to Dennis Sheahan for his beautiful and detailed cover drawing for this history Lastly, we cannot forget the contributions of the many parishioners, their stories, and encounters that make St. Joseph Parish the spiritual, warm, inviting and supportive community it is today. It is not possible to list each by name lest one be forgotten. -Mary Ann Burridge HANDS OF LOVE........................................................................................................................................1 AREA HISTORY..........................................................................................................................................2 FORT COLLINS ..........................................................................................................................................2 AUNTY STONE............................................................................................................................................4 -

Mass Attendance Census Planned REGISTER

T CATHOUC LAITY, 3,000 STRONG, GATHER AT TWO IMPRESSIVE EVENTS IN DENVER Some 3,000 members of the of the Catholic Parent-Teacher Savoy hotel, respectively. Shown ! Justin Hannen, grand knight of Quigg Newton; and Judge Philip Moran, Joseph O’Heron, James ward Leyden, Miss Margaret Sulli J. Canavan, John Cavanagh, Wil> Catholic laity of the Archdiocese league March 20 in the Shirley- above (left) at the speakers’ table council 539, Knights of Columbus; Gilliam of the Juvenile court. Hartman, and Charles Hagus; van, and Monsignor John Mulroy; liam Higgins, Eugene O’Sullivan, of Denver gathered in the past Savoy hotel. Close to 2,000 men at the men’s annual Communion Bishop Charles Quinn, C.M., prin- ( “Register” photo by Smyth) Lt. Gov. Gordon Alcott, Arch and second row. Monsignor John James Flanagan, William Kelly, week at two impressive events. took part in the annual Com breakfast are, left to right, the |cipal speaker; Archbishop Urban At the CPTL conference speak bishop Urban J. Vehr, Mrs. James Judnic, Mrs. Leonard Swigert, Elmer Kolka, and Gregory Smith. More than 1,000 women attended munion and breakfast March 23 Rev. (Lt. Col.) Edward Gates, V. Vehr; John Bowdern, cheir- ers’ table (right) are: First row, Foley, Bishop Hubert Newell, Mrs. Robert Rumble, and Mon ("Register” photo by Van's stu the annual all-day conference at the Cathedral and the Shirley- C.M., chaplain at Lowry field; an of the breakfast; Mayor left to right. Monsignors John Leonard Campbell, the Rev. Ed signors Harold Campbell, Walter dio) Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1952 — Permission to Reproduce, Except on Mass Attendance Census Planned Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M, Friday Following Issue Number of Communions Also to Be Recorded on Sundays of May lieve crowded conditions in the re the difficulty of getting to Mass in DENVER CATHOUC In Ian organized attempt to secure be conducted on the four Sundays after the collection. -

1938 Brown and Gold Vol 20 No 12 April 15, 1938

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 4-15-1938 1938 Brown and Gold Vol 20 No 12 April 15, 1938 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1938 Brown and Gold Vol 20 No 12 April 15, 1938" (1938). Brown and Gold. 158. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/158 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1888---GOLDEN JUBILEE---1938 ---------- ------···· PLAY-APRIL 29 GET YOUR SMOKER BID FOR APRIL 28 GOirD THE PROM ---------- ---------- z 70 VOL XX, No. 12. RE.GIS COLLEGE, DENVER, COLORADO APRIL 15, 1938 COLLEGIANS AWAIT JUNIOR PROME.NADE Seventeen students received a Two Religion Essay \Outstanding Social Event of School Year Cast Works Hard grade point ratio of two or higher at the ending of the third quarter. To Perfect Play There were two freshmen, James Contests Announced jT o Be Held At Beautiful Lakewood Country Final Touches Costello and Raymond Rodriguez; Students Vie () eight sophomores, Gerald Dorsey, b E f J d A Being Added to Hobert Kildare, Paul Miles, Wil ~:hrMA;:;~:n u on vening o ues ay, pril 26 "Let No Man" liam Potter, John Roth, Charles Announcement of the contest for Cramer's Collegiate Orchestra l With their initial perform Salmon, James Schlafly, and Fred the Bishop Vehr Award was made to Furnish Music ance set for but a few days Van Valkenburg; three juniors, this week. -

Call to Catholic Education Is New Modern Crusade DENVER

■I member of Audit Bureau of Cireulationi Call to Catholic Education Is New Modern Crusade Contonta Copyrighted by the Catholic Preai Society, Inc. 1946— Permiaeion to reproduce. Except on Articles Otherwise Marked, given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue I Increased Vacation Tlill[[ Ctt[BIIIT[ Church College Must ': I School Enrollment Bear Heavy Attack of 1ST M ISSIS III DENVER CATHOUC ;fll Expocted This Year E Forces of Secularism N of even a week-end rest period Friday to be at their mission sta Three newly ordained archdioce was taken by many Denver sisters tions Sunday morning. Some vaca san priests celebrated their first Bishop Edwin V. O’Hara Pioints Out Role in in their transition from parbchial tion schools will open later in the Solemn Masses Sunday, June 2, schools to vacation schools' this summer, but most of them began REGISTER in Denver churches. 'The Cathe week, as the 24th year of vacation this week. Pastors everywhere ex dral was the scene of the Mass The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Servicp Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Life of Ohurch Today as Loretto school activity in Colorado became pect larger enrollments because of offered by the Rev. Leonard A. Eiave Also the International News Service .(Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven SmaUer a reality. The sisters moved improved travel conditions. Abercombie, with a sermon by Services^ Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) Heights Graduates 23 quickly from their city convents Archdiocesan vacation schools the Rt. Rev. Stonsignor Hugh after parochial school closings last definitely reported to the Arch L.