The Automaton Within Man Ray's Films: From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Art on the Page

Art on the page Toward a modern illustrated book When Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard issued his first publication, Parallèlement, in 1900, a collection of poems by Paul Verlaine illustrated with lithographs by Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard, he ushered in a new form of illustrated book to mark the new century. In the following decades, he and other entrepreneurial art publishers such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Albert Skira would take advantage of a widening pool of book collectors interested in modern art by producing deluxe books that featured original prints by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, André Derain and others. These books are generally referred to as livres des artistes and, unlike the fine press publications produced by the Kelmscott Press, the Doves Press or Ashendene Press, the earliest examples were distinguished by their modernity. Breon Mitchell, in his introduction to Beyond illustration, argues that the livre d’artiste can be differentiated from the traditional book in several respects: The illustrations are, in each case, original works of art (woodcuts, lithographs, etchings, engravings) executed by the artist himself and printed under his supervision. The book thus contains original graphics of the kind which find their place on museum walls … The livre d’artiste is also defined by the stature of the artist. Virtually every major painter and sculptor of the twentieth century—Picasso, Braque, Ernst, Matisse, Kokoschka, Barlach, Miró, to name a few—has collaborated in the creation of one or more such works. In many cases, book illustration has occupied such an important place in the total oeuvre of the artist that no student of art history can safely ignore it. -

Drawing Surrealism Didactics 10.22.12.Pdf

^ Drawing Surrealism Didactics Drawing Surrealism is the first-ever large-scale exhibition to explore the significance of drawing and works on paper to surrealist innovation. Although launched initially as a literary movement with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, surrealism quickly became a cultural phenomenon in which the visual arts were central to envisioning the world of dreams and the unconscious. Automatic drawings, exquisite corpses, frottage, decalcomania, and collage are just a few of the drawing-based processes invented or reinvented by surrealists as means to tap into the subconscious realm. With surrealism, drawing, long recognized as the medium of exploration and innovation for its use in studies and preparatory sketches, was set free from its associations with other media (painting notably) and valued for its intrinsic qualities of immediacy and spontaneity. This exhibition reveals how drawing, often considered a minor medium, became a predominant mode of expression and innovation that has had long-standing repercussions in the history of art. The inclusion of drawing-based projects by contemporary artists Alexandra Grant, Mark Licari, and Stas Orlovski, conceived specifically for Drawing Surrealism , aspires to elucidate the diverse and enduring vestiges of surrealist drawing. Drawing Surrealism is also the first exhibition to examine the impact of surrealist drawing on a global scale . In addition to works from well-known surrealist artists based in France (André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, among them), drawings by lesser-known artists from Western Europe, as well as from countries in Eastern Europe and the Americas, Great Britain, and Japan, are included. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Tristan Tzara

DADA Dada and dadaism History of Dada, bibliography of dadaism, distribution of Dada documents International Dada Archive The gateway to the International Dada Archive of the University of Iowa Libraries. A great resource for information about artists and writers of the Dada movement DaDa Online A source for information about the art, literature and development of the European Dada movement Small Time Neumerz Dada Society in Chicago Mital-U Dada-Situationist, an independent record-label for individual music Tristan Tzara on Dadaism Excerpts from “Dada Manifesto” [1918] and “Lecture on Dada” [1922] Dadart The site provides information about history of Dada movement, artists, and an bibliography Cut and Paste The art of photomontages, including works by Heartfield, Höch, Hausmann and Schwitters John Heartfield The life and work of the photomontage artist Hannah Hoch A collection of photo montages created by Hannah Hoch Women Artists–Dada and Surrealism An excerpted chapter from Margaret Barlow’s illustrated book Women Artists Helios A beginner’s guide to Dada Merzheft German Dada, in German Dada and Surrealist Film A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library La Typographie Dada D.E.A. memoir in French by Breuil Eddie New York Avant-Garde, 1913-1929 New York Dada and the Armory Show including images and bibliography Excentriques A biography of Arthur Cravan in French Tristan Tzara, a Biography Excerpt from François Buot’s biography of Tzara,L’homme qui inventa la Révolution Dada Tristan Tzara A selection of links on Tzara, founder of the Dada movement Mina Loy’s lunar odyssey An online collection of Mina Loy’s life and work Erik Satie The homepage of Satie 391 Experimental art inspired by Picabia’s Dada periodical 391, with articles on Picabia, Duchamp, Ball and others Man Ray Internet site officially authorized by the Man Ray Trust to offer reproductions of the Man Ray artworks. -

Documents (Pdf)

Documents_ 18.7 7/18/01 11:40 AM Page 212 Documents 1915 1918 Exhibition of Paintings by Cézanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, Tristan Tzara, 25 poèmes; H Arp, 10 gravures sur bois, Picabia, Braque, Desseignes, Rivera, New York, Zurich, 1918 ca. 1915/16 Flyer advertising an edition of 25 poems by Tristan Tzara Flyer with exhibition catalogue list with 10 wood engravings by Jean (Hans) Arp 1 p. (folded), 15.3x12 Illustrated, 1 p., 24x16 1916 Tristan Tzara lira de ses oeuvres et le Manifeste Dada, Autoren-Abend, Zurich, 14 July 1916 Zurich, 23 July 1918 Program for a Dada event in the Zunfthaus zur Waag Flyer announcing a soirée at Kouni & Co. Includes the 1 p., 23x29 above advertisement Illustrated, 2 pp., 24x16 Cangiullo futurista; Cafeconcerto; Alfabeto a sorpresa, Milan, August 1916 Program published by Edizioni futuriste di “Poesia,” Milan, for an event at Grand Eden – Teatro di Varietà in Naples Illustrated, 48 pp., 25.2x17.5 Pantomime futuriste di Francesco Cangiullo, Rome, 1916 Flyer advertising an event at the Club al Cantastorie 1 p., 35x50 Galerie Dada envelope, Zurich, 1916 1 p., 12x15 Stationary headed ”Mouvement Dada, Zurich,“ Zurich, ca. 1916 1 p., 14x22 Stationary headed ”Mouvement Dada, Zeltweg 83,“ Zurich, ca. 1916 Club Dada, Prospekt des Verlags Freie Strasse, Berlin, 1918 1 p., 12x15 Booklet with texts by Richard Huelsenbeck, Franz Jung, and Raoul Hausmann Mouvement Dada – Abonnement Liste, Zurich, ca. 1916 Illustrated, 16 pp., 27.1x20 Subscription form for Dada publications 1 p., 28x20.5 Centralamt der Dadaistischen Bewegung, Berlin, ca. 1918–19 1917 Stationary of Richard Huelsenbeck with heading of the Sturm Ausstellung, II Serie, Zurich, 14 April 1917 Dada Movement Central Office Catalogue of an exhibition at the Galerie Dada. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Cat151 Working.Qxd

Catalogue 151 election from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. Illustrations de Jean Arp. (Collection “Pour Mes Amis.” II.) 23, (5)pp. 35 illustrations and ornaments by Arp (2 full-page), integrated with the text. -

Press Preview, Jean Arp. No. 72

I rt FOR RELEASE: Wednesday, October 8, 1958 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PRESS PREVIEW: 11 WEST S3 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. Tuesday, October 7> 1958 TIIIPHONI: CIRCLE 5-8900 11 a.m. - k p.m. No. 72 More than 100 collages, string pictures, wood reliefs and stone sculptures by Jean Arp will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street from October 8 through November 30. The retrospective of work by the 71-year old artist is one of four shows marking the re-opening of the Museum after a four month period devoted to renovating the building.. The exhibition was selected from 52 public and private collections here and abroad by James Thrall Soby, Chairman of the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture. It includes collages from 1915 when Arp joined friends in Zurich in founding the "Dada" movement, string pictures and wood reliefs of the 20's, when be exhibited with the Surrealists in France, and more than U5 sculptures in marble, limestonfi and bronze from the past two decades which have won him his place as one o the major sculptois of our century. Installation is by Rene d'Harnoncourt, Director of the Museum. "Arp's world wide fame is based in part on the authority he has brought to biomorphic forms," Kr» Soby points out. ,! 'Art, he says,, is a fruit that grows in man, like a fruit on a plant or a child in its mother's womb.' To familiar, even commonplace objects, animate and inanimate—moustaches, forks, navels, eggs, leaves, clouds, birds, snakes, shirt fronts—he gives a hieratic dignity. -

Guest Biographies Booklet

CREDITS Game Design by Mary Flanagan & Max Seidman • Illustration by Virginia Mori • Graphic Design by Spring Yu • Writing and Logistics by Danielle Taylor • Production & Web by Sukdith Punjasthitkul • Community Management by Rachel Billings • Additional Game Design by Emma Hobday • Playtesting by Momoka Schmidt & Joshua Po Special thanks to: Andrea Fisher and the Artists Rights Society The surrealists’ families and estates Hewson Chen Our Kickstarter backers Lola Álvarez Bravo LOW-la AL-vah-rez BRAH-vo An early innovator in photography in Mexico, Lola Álvarez Bravo began her career as a teacher. She learned photography as an assistant and had her first solo exhibition in 1944 at Mexico City’s Palace of Fine Arts. She described the camera as a way to show “the life I found before me.” Álvarez Bravo was engaged in the Mexican surrealist movement, documenting the lives of many fellow artists in her work. Jean Arp JON ARP (J as in mirage) Jean Arp (also known as Hans Arp), was a German-French sculp- tor, painter, and writer best known for his paper cut-outs and his abstract sculptures. Arp also created many collages. He worked, like other surrealists, with chance and intuition to create art instead of using reason and logic, later becoming a member of the “Abstraction-Création” art movement. 3 André Breton ahn-DRAY bruh-TAWN A founder of surrealism, avant-garde writer and artist André Breton originally trained to be a doctor, serving in the French army’s neuropsychiatric center during World War I. He used his interests in medicine and psychology to innovate in art and literature, with a particular interest in mental illness and the unconscious. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination. -

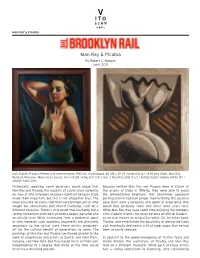

Man Ray & Picabia

MAN RAY & PICABIA Man Ray & Picabia By Robert C. Morgan April, 2021 Left: Francis Picabia, Femme à la chemise bleue, 1942-43. Oil on board, 40 3/8 x 29 1/2 inches (102.6 x 74.93 cm). Right: Man Ray, Peinture Feminine, 1954. Oil on canvas, 50 x 43 3/4 inches (127 x 111.1 cm). © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2021. Historically speaking, some observers would argue that Because neither Man Ray nor Picabia were in Zurich at Man Ray and Picabia, the subjects of a joint show currently the origins of Dada in 1915–16, they were able to avoid on view at Vito Schnabel, became important because Dada the premeditated intentions that sometimes governed made them important. But this is not altogether true. The participation in Dadaism proper. Inadvertently, this absence more accurate version is that they were brilliant artists who gave their work a longevity and depth of experience that sought out connections with Marcel Duchamp, each on a would only gradually come into focus some years later. different occasion. There is little doubt that Duchamp felt a While Man Ray may have spent time enjoying the company strong connection with them on both a deeply personal and of his Dadaist friends, he never became an official Dadaist— an artistic level. While interesting from a modernist point or, for that matter, an official Surrealist. On the other hand, of view, however, such academic arguments are ultimately Picabia, who entertained the possibility of joining the Dada secondary to the actual work these artists produced— cult, eventually declined in a fit of rage, angry that he had art for the cultural benefit of generations to come.