Re-Conceptualising Aboriginal Mobilities 5.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborigines Department

1900. WESTERN AUSTRALIA ABORIGINES DEPARTMENT. REPORT FOR FINANCIAL YEAR ENDING 30TH JUNE, 1900. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by His Excellency's Command. (.SECOND SESSION OF 1900.] PERTH: BY AUTHORITY : RICHARD PETHER, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. 1900. No. 15. Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2008-www.aiatsis.gov.au/library ABORIGINES DEPARTMENT. Report for Financial Year ending 80th June, 1900. THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE PREMIER, SIR, I beg to submit my Report on the working of the Aborigines Department for the year ending 80th June, 1900. Expenditure.—The expenditure of the Department for the said year has been £9,802 16s. 8d. The statutory vote of £5,000 appearing by previous experience to be inadequate for the duties before the Department, you were kind enough to recommend a supplementary .£5,000 on the Estimates for the year, which was voted by the Legislature; and I am glad to be able to inform you that, by the exercise of a strict supervision of the expenses, I have been able to confine the expenditure just within that amount. The balance-sheet required by Section 10 of "The Aborigines Act, 1897" (61 Vict., No. 5), which I attach for presentation to the Legislature, will show that £222 9s. 7d. remain unexpended. I am happy to be able to say that no direct complaints have been made of any distress among the Aborigines which has not been relieved, and that very few complaints of any sort have been made. By the energetic manner in which the Travelling Inspector appointed last August has carried out his duties, I am now gradually recording a very detailed register of the condition and numbers, sexes, etc., of all the working aboriginal population; and it is owing to the enormous extent of country that he must travel over that it is still incomplete, so I will not attempt this year to put forward in detail the results of his work. -

Latukefu.R02.Cs.Pdf

************************************************************** * * * WARNING: Please be aware that some caption lists contain * * language, words or descriptions which may be considered * * offensive or distressing. * * These words reflect the attitude of the photographer * * and/or the period in which the photograph was taken. * * * * Please also be aware that caption lists may contain * * references to deceased people which may cause sadness or * * distress. * ************************************************************** Scroll down to view captions LATUKEFU.R02.CS (000140850-000140987) Community portraits in the Murchison Gasgoyne region Mullewa, Yalgoo, Geraldton, Wooleen, Carnarvon, Tardun, Meeberie, Jigalong, Meekatharra, Wiluna, Warburton Ranges, W.A., 1955-1957 Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140850 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. Title: Mullewa railW.A.y line Photographer/Artist: Latukefu, Ruth Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140851 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. Title: RailW.A.y footbridge leading to camps across tracks Photographer/Artist: Latukefu, Ruth Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140852 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. Title: Mullewa camp Photographer/Artist: Latukefu, Ruth Access: Conditions apply Notes: Tents housed station visitors, more permanent residents had timber and corrugated iron shelters ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140853 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. Title: Man carting W.A.ter from the railW.A.y tap Photographer/Artist: Latukefu, Ruth Access: Conditions apply Notes: No W.A.ter near the camps in 1955-57 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140854 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. Title: Sunday morning people drinking tea at Mullewa camp Photographer/Artist: Latukefu, Ruth Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: LATUKEFU.R02.CS-000140855 Date/Place taken: 1955 : Mullewa, W.A. -

Bushfire Brigade Annual General Meeting

BUSHFIRE BRIGADE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA FOR THE SHIRE OF MINGENEW BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING TO BE HELD AT THE SHIRE CHAMBERS ON 25 MARCH 2019 COMMENCING AT 6PM. 1.0 DECLARATION OF OPENING 2.0 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE / APOLOGIES ATTENDEES To be confirmed APOLOGIES Vicki Booth – A/Area Officer – Fire Services Midwest (DFES) 3.0 CONFIRMATION OF PREVIOUS MEETING MINUTES 3.1 BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ MEETING HELD 02 OCTOBER 2018 BRIGADES’ DECISION – ITEM 3.1 Moved: Seconded: That the minutes of the Bushfire Brigades’ Annual General Meeting of the Shire of Mingenew held 02 October 2018 be confirmed as a true and accurate record of proceedings. VOTING DETAILS: 4.0 OFFICERS REPORTS 4.1 Chief Bush Fire Control Officer Report- Murray Thomas • Overview of the 2018/19 Fire Season • Gazetted change in Shires Restricted Burning Times- now changed from the 17th September to the 1st October. All other timeframes remain the same (Prohibited- 1 Nov- 31 Jan, Restricted 1 October-15 March, open season 16 March- 30 September). This means that the CBFCO can now shorten or lengthen that new restricted date by 14 days depending on seasonal conditions (so restricted timeframe can potentially be pushed out to 17 September-31 October or shortened to 14 October-31 October). 4.2 Captains Reports- All Captains to remark on level of training of its volunteers and any identified gaps or training requirements. MINGENEW BUSHFIRE ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING AGENDA – 26 September 2017 4.2.1 Yandanooka 4.2.2 Lockier 4.2.3 Guranu 4.2.4 Mingenew North 4.2.5 Mingenew Town 4.3 Shire CEO Report • 2017/18 Operating Grant has been fully expended and acquitted. -

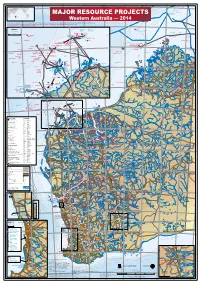

Major-Resource-Projects-Map-2014.Pdf

112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° 10° 10° JOINT PETROLEUM DEVELOPMENT AREA MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS Laminaria East Western Australia — 2014 Major projects operating or under development in 2013 with an actual/anticipated value of annual production of greater than $A10 million are shown in blue NORTHERN TERRITORY Proposed or potential major projects with a capital expenditure estimated to be greater than $A20 million are shown in red WESTERN AUSTRALIA Care and maintenance projects are shown in purple 114° 116° m 3000 Ashmore Reef West I 12° Mutineer East I INSET A Fletcher Middle I 2000 m 2000 12° Exeter Finucane TERRITORY OF ASHMORE SCALE 1:1 200 000 AND CARTIER ISLANDS INDONESIA Lambert Deep AUSTRALIA T I M O R S E A 50 km Eaglehawk Hermes Larsen Deep Egret Lambert Noblige Searipple Athena SHELF Angel Prometheus Montague m 1000 Larsen Capella Petrel Perseus Persephone Cossack Wanaea Forestier Ajax North Rankin COMMONWEALTH 'ADJACENT AREAS' BOUNDARY Chandon Gaea Hurricane Frigate Tern Keast Goodwyn Goodwyn S/Pueblo Holothuria Reef Echo/Yodel Crown Trochus I Yellowglen Rankin/Sculptor Tidepole Mimia Dockrell Kronos Concerto/Ichthys Cornea Otway Bank Urania Troughton I Io Pemberton WEST Echuca Shoals Cape Londonderry Dixon/W.Dixon Ichthys West SIR GRAHAM Cape Wheatstone Prelude MOORE Is Ta lb ot Sage Parry HarbourTroughton Passage Lesueur I Ichthys Eclipse Is Jansz Pluto Cassini I Cape Rulhieres Iago Saffron Torosa Mary I Geryon Eris 20° Browse I Oyster Rock Passage Vansittart NAPIER Blacktip Bay BROOME Io South Reindeer Cape -

Economics and Industry Standing Committee

ECONOMICS AND INDUSTRY STANDING COMMITTEE 2009-2010 ANNUAL REPORT Report No. 5 in the 38th Parliament 2010 Published by the Legislative Assembly, Parliament of Western Australia, Perth, September, 2010. Printed by the Government Printer, State Law Publisher, Western Australia. Economics and Industry Standing Committee 2009-2010 Annual Report ISBN: 978-1-921355-97-4 (Series: Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees. Economics and Industry Standing Committee. Report 5) 328.365 Copies available from: State Law Publisher 10 William Street PERTH WA 6000 Telephone: (08) 9321 7688 Facsimile: (08) 9321 7536 Email: [email protected] Copies available on-line: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/ ECONOMICS AND INDUSTRY STANDING COMMITTEE 2009-2010 ANNUAL REPORT Report No. 5 Presented by: Dr M.D. Nahan, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly on 23 September 2010 ECONOMICS AND INDUSTRY STANDING COMMITTEE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Chair Dr M.D. Nahan, MLA Member for Riverton Deputy Chair Mr W.J. Johnston, MLA Member for Cannington Members Mrs L.M. Harvey, MLA Member for Scarborough Mr M.P. Murray, MLA Member for Collie-Preston Mr J.E. McGrath, MLA Member for South Perth COMMITTEE STAFF Principal Research Officer Dr Loraine Abernethie, PhD (until 27 May 2010) Mr Tim Hughes, BA (Hons) (from 27 May 2010) Research Officer Ms Vanessa Beckingham, BA (Hons) (until 22 February 2010) Mrs Kristy Bryden, BCom, BA (from 22 February 2010) COMMITTEE ADDRESS Economics and Industry Standing Committee Legislative Assembly Tel: (08) 9222 7496 Parliament House Fax: (08) 9222 7804 Harvest Terrace Email: [email protected] PERTH WA 6000 Website: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/eisc - i - ECONOMICS AND INDUSTRY STANDING COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS COMMITTEE MEMBERS ........................................................................................................... -

Major Resource Projects, Western Australia

112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° 10° 10° JOINT PETROLEUM MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS DEVELOPMENT AREA Western Australia — 2021 Principal resource projects operating with sales >$5 million in 2019–20 are in blue text NORTHERN TERRITORY WESTERN AUSTRALIA Resource projects currently under construction are in green text m 3000 Planned mining and petroleum projects with at least a pre-feasibility study (or equivalent) completed are in red text Principal resource projects recently placed on care and maintenance, or shut are in purple text Ashmore Reef West I East I 12° 114° 116° Middle I 2000 m 2000 TERRITORY OF ASHMORE 12° INSET A AND CARTIER ISLANDS T I M O R S E A SCALE 1:1 200 000 50 km Hermes Lambert Athena m 1000 Angel Searipple Persephone Cossack INDONESIA Perseus Wanaea AUSTRALIA North Rankin SHELF COMMONWEALTH 'ADJACENT AREAS' BOUNDARY Chandon Goodwyn Holothuria Reef Keast Trochus I Sculptor Tidepole Dockrell Pyxis Lady Nora Pemberton Prelude Troughton I Cape Londonderry SIR GRAHAM Cape Wheatstone Talbot Ichthys Parry HarbourTroughton Passage MOORE IS Lesueur I Jansz–Io Eclipse Is Pluto Cassini I Cape Rulhieres WEST Mary I Iago Torosa NAPIER 20° Browse I Oyster Rock Passage Vansittart Xena BROOME Blacktip Bay Scott Reef Fenelon I BAY 200 m 200 Yankawinga I Reindeer Kingsmill Is 14° Cone Mountain RIVER JOSEPH BONAPARTE 14° Brunello Brecknock Maret Is Prudhoe Is MONTAGUE ADMIRALTY GULF 20° Chrysaor/Dionysus Turbin I SOUND GULF Reveley I Calliance Warrender Hill RIVER Carson River Buckle Head Wandoo GEORGE BIGGE I Mt Connor Mt -

1:100 000 Geological Maps

1:100 000 GEOLOGICAL MAPS Revision in progress LONDONDERRY SD 52-5 Map and Explanatory Notes TROUGHTON LONDONDERRY RUHLIERES 4170 4270 4370 Map ADMIRALTY KING MARET MONTALIVET GULF VANSITTART DRYSDALE GEORGE CASUARINA 3869 3969 4069 4169 4269 4369 4469 MONTAGUE SOUND DRYSDALE MEDUSA BANKS Digital data (captured from existing map) SD 51-12 SD 52-9 SD 52-10 BUFFON BIGGE WARRENDER KING EDWARD CARSON COLLISON BERKELEY MEDUSA KNOB PEAK 3868 3968 4068 4168 4268 4368 4468 4568 4668 Digital data (no map planned) PRINCE CHAMPAGNY BRUNSWICK FREDERICK BRADSHAW COUCHMAN ASHTON ERNEST MILLIGAN WYNDHAM CARLTON 3767 3867 3967 4067 4167 4267 4367 4467 4567 4667 Map/Digital data in preparation/progress CAMDEN SOUND PRINCE REGENT ASHTON CAMBRIDGE GULF SD 51-15 SD 51-16 SD 52-13 SD 52-14 COCKELL METHUEN PRINCE HANN WOODHOUSE CAMM BEATRICE PENTECOST ERSKINE KUNUNURRA REGENT 3866 4066 4166 4266 4366 4466 4566 4666 Fieldwork planned 3766 3966 16° DUNHAM ARGYLE ANZAC SHOAL SUNDAY YAMPI COLLIER BAY ELGEE LEVEQUE ISLAND WALCOTT EDKINS JAMESON GIBB SULLIVAN KARUNJIE RIVER DOWNS Geoscience Australia map and 3365 3465 3565 3665 3765 3865 3965 4065 4165 4265 4365 4465 4565 4665 Explanatory Notes PENDER YAMPI CHARNLEY MOUNT ELIZABETH LISSADELL SE 51-2 SE 51-3 SE 51-4 PACKHORSE SE 52-1 SE 52-2 BALEINE LACEPEDE PENDER CORNAMBIE KIMBOLTON TARRAJI MATTHEW ISDELL RANGE BARNETT SIDDINS SALMOND CHAMBERLAIN BOW LISSADELL Geoscience Australia map 3264 3364 3464 3564 3664 3764 3864 3964 4064 4164 4264 4364 4464 4564 4664 MOUNT TURKEY RICHENDA MOUNT Explanatory Notes in: Report -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community. -

QON LC 1875 – Pastoral Leases

QON LC 1875 – Pastoral leases Station Name Lease Total Station Name Lease Total Number Station Number Station Area (ha) Area (ha) ADELONG N050386 108,793 BOODARIE N050445 64,620 ALBION DOWNS N049530 140,509 N050447 9,694 ALICE DOWNS N050018 136,974 BOOGARDIE N050334 161,073 ANNA PLAINS N050392 392,324 BOOLARDY N049598 333,964 ANNEAN N050577 163,909 BOOLATHANA N050616 143,264 N050578 25,531 BOOLOGOORO N050380 3,667 ARUBIDDY N049537 314,394 N050381 65,272 ASHBURTON N050036 311,235 BOONDEROO N050420 308,923 DOWNS BOOYLGOO N050557 233,339 ATLEY N050586 353,558 SPRING AUSTIN DOWNS N050063 162,917 BOW RIVER N049619 300,878 AVOCA DOWNS N049885 121,392 BRAEMORE N049916 13,255 BADJA N049542 113,653 BRICK HOUSE N050631 224,243 BALFOUR N049548 85,926 BROOKING N050173 10,615 DOWNS N049553 345,254 SPRINGS N050174 183,258 BALGAIR N049892 289,316 BRYAH N049600 122,689 BALLADONIA N050098 46,266 BULGA DOWNS N050442 273,949 N050099 175,878 BULKA N050503 274,749 BALLYTHUNNA N050597 124,556 BULLABULLING N049612 94,038 BANJAWARN N050400 406,813 BULLARA N050158 109,501 BARRAMBIE N049557 100,564 BULLARDOO N049633 41,942 BARWIDGEE N049559 276,396 BULLOO DOWNS N049943 40,6489 BEDFORD N050413 376,963 BUNNAWARRA N049947 90,154 DOWNS BURKS PARK N049650 8,133 BEEBYN N049894 59,815 BUTTAH N049656 147,843 BEEFWOOD PARK N050113 14,831 BYRO N050480 237,872 N050132 21,535 CALLAGIDDY N050519 65,380 N050147 169,189 CALOOLI N050390 12,383 BELELE N049563 279,705 CARBLA N050530 95,193 BERINGARRA N050464 140,323 CARDABIA N049635 193,753 BIDGEMIA N050619 372,375 CAREY DOWNS N049938 -

Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment

SKA Ecological Assessment Commercial-in-Confidence Department of Industry 28-Nov-2014 Doc No. 60327857-RPT-0001 Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment G:\60327857 - SKA EcologicalSurvey\8. Issued Docs\8.1 Reports\Ecological Assessment\60327857-SKA Ecological Report_Rev0.docx Revision 0 – 28-Nov-2014 Prepared for – Department of Industry – ABN: 74 599 608 295 AECOM SKA Ecological Assessment Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment Commercial-in-Confidence Square Kilometre Array Ecological Assessment Client: Department of Industry ABN: 74 599 608 295 Prepared by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd 3 Forrest Place, Perth WA 6000, GPO Box B59, Perth WA 6849, Australia T +61 8 6208 0000 F +61 8 6208 0999 www.aecom.com ABN 20 093 846 925 28-Nov-2014 Job No.: 60327857 AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to the latest version of ISO9001, ISO14001, AS/NZS4801 and OHSAS18001. © AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM). All rights reserved. AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. -

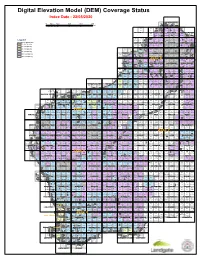

(DEM) Coverage Status Index Date : 22/05/2020

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Coverage Status Index Date : 22/05/2020 LONDONDERRY 0 62.5 125 250 375 500 4070 4170 4270 4370 km LONG REEF TROUGHTON LONDONDERRY RULHIERES 3669 3869 3969 4069 4169 4269 4369 4469 BROWSE MARET MONTALIVET ADMIRALTY GULF VANSITTART DRYSDALE KING GEORGE CASUARINA BROWSE ISLANDMONTAGUE SOUND DRYSDALE MEDUSA BANKS 3868 3968 4068 4168 4268 4368 4468 4568 4668 BUFFON BIGGE WARRENDER KING EDWARD CARSON COLLISON BERKELEY MEDUSA KNOB PEAK 3567 3667 3767 3867 3967 4067 4167 4267 4367 4467 4567 4667 BRUNSWICK Legend FRASER INLET BEAGLE REEF CHAMPAGNY BRADSHAW COUCHMAN ASHTON ERNEST MILLIGAN WYNDHAM CARLTON PRINCE FREDERICK DEM_USED_FOR_RECTIFICATION CAMDEN SOUND PRINCE REGENT ASHTON CAMBRIDGE GULF 1m Grid Spacing 3566 3666 3766 3866 3966 4066 4166 4266 4366 4466 4566 4666 ADELE MACLEAY COCKELL METHUEN PRINCE REGENT HANN WOODHOUSE CAMM BEATRICE PENTECOST ERSKINE KUNUNURRA 2m Grid Spacing 3m Grid Spacing 3365 3465 3565 3665 3765 3865 3965 4065 4165 4265 4365 4465 4565 4665 ANZAC SHOAL LEVEQUE SUNDAY ISLAND YAMPI COLLIER JAMESON GIBB SULLIVAN KARUNJIE ELGEE DUNHAM ARGYLE DOWNS 5m Grid Spacing WALCOTT EDKINS PENDER YAMPI 3864 CHARNLEY4064MOUNT ELIZABETH LISSADELL 10m Grid Spacing 3264 3364 3464 3564 3664 3764 3964 4164 4264 4364 4464 4564 4664 MATTHEW ISDELL PACKHORSE Rg. 20m Grid Spacing BALEINE LACEPEDE PENDER CORNAMBIE KIMBOLTON TARRAJI BARNETT SIDDINS SALMOND CHAMBERLAIN BOW LISSADELL 3363 3463 3563 3663 3763 3Z863 on396e3 64063 4163 4263 4363 4463 4563 4663 Mt. REMARKABLE CARNOT JOWLAENGA FRASER DERBY MEDA GLENROY TABLELAND -

A Report on the Viability of Pastoral Leases in the Northern Rangelands Region Based on Biophysical Assessment

A Report on the Viability of Pastoral Leases in the Northern Rangelands Region Based on Biophysical Assessment Dr PE Novelly - South Perth Mr D Warburton - Northam 7 September 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kimberley and Pilbara comprise Western Australia’s Northern Rangelands. The pastoral industry of both regions is becoming increasingly similar, with most formerly sheep producing properties in the Pilbara moving to cattle, more control and manipulation of herds, and enterprises with a higher proportion of breeders. The projected viability (based on a capacity to carry a minimum number of stock in an ecologically sustainable manner) of pastoral leases in this region was analysed through assessment of biophysical parameters, in particular the inherent landscape productivity and its capacity to be managed in an ecologically sustainable manner, and the impact of current rangeland condition on grazing capacity. Analysis was conducted on individual pastoral leases The effect of leases being run in combination with other leases in one business, or access to substantial non-pastoral income was ignored. Of the 154 pastoral leases assessed, applying a threshold viability level of a potential carrying capacity of 4,000 cattle units, but ignoring reduced carrying capacity caused by degraded rangeland condition: • 16 leases in the Kimberley and 37 leases in the Pilbara do not reach the viability threshold when all land systems within the lease area are considered; • 18 Kimberley leases and 40 Pilbara leases do not meet the viability threshold when land systems whose pastoral potential is so low that investment in management and infrastructure is considered non-viable are excluded. The background and arguments behind this assessment are discussed.