Submission to the 12Th ASEAN SUMMIT 11-14 December 2006 CEBU, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Session document 4.9.2007 B6-0337/2007 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for the debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 115 of the Rules of Procedure by Vittorio Agnoletto on behalf of the GUE/NGL Group on human rights in Burma-Myanmar RE\P6_B(2007)0337_EN.doc PE 394.758v0 EN EN B6-0337/2007 European Parliament resolution on human rights in Burma-Myanmar The European Parliament, – having regard to its previous resolutions on Burma, – having regard to the statement by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, of 25 May 2007, calling for 'restrictions on Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political figures' to be lifted, – having regard to the letter to the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, signed by 92 Burmese MPs-Elect, of 1 August 2007, which includes a proposal for National Reconciliation and democratization in Burma; – having regard to the letter of 15 May 2007 to General Than Shwe, signed by 59 former heads of State, calling for 'the immediate release of the world’s only imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi', – having regard to Rule 115(5) of its Rules of Procedure, A. whereas the NDL leader, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and Sakharov Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, has spent 11 of the last 17 years under house arrest; whereas on 25 May 2007 the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) extended the illegal detention of Aung San Suu Kyi for another year, B. -

Myanmar AI Index: ASA 16/034/2007 Date: 23 October 2007

Amnesty.org feature Eighteen years of persecution in Myanmar AI Index: ASA 16/034/2007 Date: 23 October 2007 On 24 October 2007, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi will have spent 12 of the last 18 years under detention. She may be the best known of Myanmar’s prisoners of conscience, but she is far from the only one. Amnesty International believes that, even before the recent violent crackdown on peaceful protesters, there were more than 1,150 political prisoners in the country. Prisoners of conscience among these include senior political representatives of the ethnic minorities as well as members of the NLD and student activist groups. To mark the 18th year of Aung San Suu Kyi's persecution by the Myanmar, Amnesty International seeks to draw the world's attention to four people who symbolise all those in detention and suffering persecution in Myanmar. These include Aung San Suu Kyi herself; U Win Tin, Myanmar's longest-serving prisoner of conscience; U Khun Htun Oo, who is serving a 93 year sentence; and Zaw Htet Ko Ko, who was arrested after participating in the recent demonstrations in the country. Read more about these four people: Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won the general elections in Myanmar in 1990. But, instead of taking her position as national leader, she was kept under house arrest by the military authorities and remains so today. At 62, Aung San Suu Kyi is the General Secretary and a co-founder of Myanmar’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD). -

Old and New Competition in Myanmar's Electoral Politics

ISSUE: 2019 No. 104 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |17 December 2019 Old and New Competition in Myanmar’s Electoral Politics Nyi Nyi Kyaw* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Electoral politics in Myanmar has become more active and competitive since 2018. With polls set for next year, the country has seen mergers among ethnic political parties and the establishment of new national parties. • The ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party faces more competition than in the run up to the 2015 polls. Then only the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) represented a serious possible electoral rival. • The NLD enjoys the dual advantage of the star power of its chair State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and its status as the incumbent ruling party. • The USDP, ethnic political parties, and new national parties are all potential contenders in the general elections due in late 2020. Among them, only ethnic political parties may pose a challenge to the ruling NLD. * Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore and Visiting Fellow at the University of Melbourne. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 104 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The National League for Democracy (NLD) party government under Presidents U Htin Kyaw and U Win Myint1 and State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been in power since March 2016, after it won Myanmar’s November 2015 polls in a landslide. Four years later, the country eagerly awaits its next general elections, due in late 2020. -

The Steel Butterfly: Aung San Suu Kyi Democracy Movement in Burma

presents The Steel Butterfly: Aung San Suu Kyi and the Democracy Movement in Burma Photo courtesy of First Post Voices Against Indifference Initiative 2012-2013 Dear Teachers, As the world watches Burma turn toward democracy, we cannot help but wish to be part of this historic movement; to stand by these citizens who long for justice and who so richly deserve to live in a democratic society. For 25 years, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi endured house arrest because of her unwavering belief in, and fight for, democracy for all the people of Burma. Through her peaceful yet tireless example, Madam Suu Kyi has demonstrated the power of the individual to change the course of history. Now, after 22 years, the United States of America has reopened diplomatic relations with Burma. President Barack Obama visited in November 2012, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited in December 2011 and, in July of 2012, Derek Mitchell was appointed to represent our country as Ambassador to Burma. You who are the teachers of young people, shape thinking and world views each day, directly or subtly, in categories of learning that cross all boundaries. The Echo Foundation thanks you for your commitment to creating informed, compassionate, and responsible young people who will lead us into the future while promoting respect, justice and dignity for all people. With this curriculum, we ask you to teach your students about Burma, the Burmese people, and their leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. The history of Burma is fascinating. Long in the margins of traditional studies, it deserves to come into the light so that we may join the people of Burma in their quest for a stable democracy. -

A Study of Myanmar-US Relations

INDEX A strike at Hi-Mo factory and, 146, “A Study of Myanmar-US Relations”, 147 294 All Burma Students’ Democratic abortion, 318, 319 Front, 113, 125, 130 n.6 accountability, 5, 76 All India Radio, 94, 95, 96, 99 financial management and, 167 All Mon Regional Democracy Party, administrative divisions of Myanmar, 104, 254 n.4 170, 176 n.12 allowances for workers, 140–41, 321 Africa, 261 American Centre, 118 African National Congress, 253 n.2 American Jewish World Service, 131 Agarwal, B., 308 n.7 “agency” of individuals, 307 Amyotha Hluttaw (upper house of Agricultural Census of Myanmar parliament), 46, 243, 251 (1993), 307 Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom Agricultural Ministers in States and League, 23 Regions, 171 Anwar, Mohammed, 343 n.1 agriculture, 190ff ANZ Bank (Australia), 188 loans for, 84 “Arab Spring”, 28, 29, 138 organizational framework of, “arbitrator [regime]”, 277 192, 193 Armed Forces Day 2012, 270 Ah-Yee-Taung, 309 armed forces (of Myanmar), 22, 23, aid, 295, 315 262, 269, 277, 333, 334 donors and, 127, 128 battalions 437 and 348, 288 Kachin people and, 293, 295 border areas and, 24 Alagappa, Muthiah, 261, 263, 264 constitution and, 16, 20, 24, 63, Albert Einstein Institution, 131 n.7 211, 265, 266 All Burma Federation of Student corruption and, 26, 139–40 Unions, 115, 121–22, 130 n.4, 130 disengagement from politics, 259 n.6, 148 expenditure, 62, 161, 165, 166 “fifth estate”, 270 356 Index “four cuts” strategy, 288, 293 Aung Kyaw Hla, 301 n.5 impunity and, 212, 290 Aung Ko, 60 Kachin State and, 165, 288, 293 Aung Min, 34, -

Summary of Current Situation Monthly Trend Analysis

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for February 2009 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2,128 political prisoners in Burma. 1 These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 15 Students 229 88 Generation Students Group 47 Women 186 NLD members 456 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network 42 Ethnic nationalities 203 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 20 Teachers 26 Media activists 43 Lawyers 15 In poor health 115 Since the protests in August 2007 leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1,052 activists have been arrested and are still in detention. Monthly trend analysis 250 In the month of February 2009, 4 200 activists were arrested, 5 were sentenced, and 30 were released. On 150 Arrested 20 February the military regime Sentenced 100 Released announced an amnesty for 6,313 50 prisoners, beginning 21 February. To date AAPP has been able to confirm 0 Nov-08 Dec-08 Jan-09 Feb-09 the release of just 30 political prisoners. This month the UN Special Envoy Ibrahim Gambari and the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar Tomas Ojea Quintana both visited Burma. At the time of the Special Rapporteur’s visit, political prisoners U Thura aka Zarganar, Zaw Thet Htway, Thant Sin Aung, Tin Maung Aye aka Gatone, Kay Thi Aung aka Ma Ei, Wai Myo Htoo aka Yan Naing, Su Su Nway and Nay Myo Kyaw aka Nay Phone Latt all had their sentences reduced. However they all still face long prison terms of between 8 years and 6 months, and 35 years. -

Monthly Chronology of Burma Political Prisoners for March 2009

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for March 2009 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2,146 political prisoners in Burma. 1 These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 15 Students 2722 Women 18 7 NLD members 458 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters 43 network Ethnic nationalities 203 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 21 Teachers 26 Media a ctivists 46 Lawyers 12 In poor health 113 Since the protests in August 2007 leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1,070 activists have been arrested and are still in detention. Monthly trend analysis During the month of March 2009, at least 22 arrested and still detained, 42 250 sentenced and 11 transferred, 7 released, 200 and 8 in bad health show the Burmese 150 Arrested regime continues to inflict human rights 100 Sentenced abuses. The UN Working Group on 50 Released Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion 0 S N Jan- Ma report which declared the detention of ep- ov- 09 r- Daw Aung San Su Kyi to be illegal and 08 08 09 in violation of the regime’s own laws. This is the first time the UNWG AD has declared that it violates the regime’s own laws. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention also ruled that the imprisonment of Min Ko Naing, Pyone Cho, Ko Jimmy and Min Zayar violates minimum standards of international Flaw. The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Burma released his report following his visit in February. The report recommendations call for the progressive release of all political prisoners. -

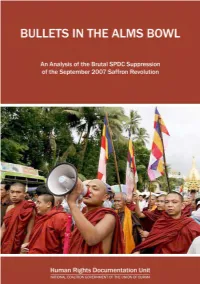

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

Vi. the Myanmar Prison System

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND......................................................................................................4 Subsequent developments..........................................................................................4 Human rights and the National Convention...............................................................6 Summary of recent arrests and releases .....................................................................8 III. UPDATE ON THE ARREST AND PRE-TRIAL DETENTION PROCESS.......10 Arbitrary arrests and detention without judicial oversight ......................................11 Torture and ill-treatment during pre-trial detention.................................................15 IV. UPDATE ON POLITICAL TRIALS AND SENTENCES...................................17 Sentencing................................................................................................................19 The death penalty.....................................................................................................20 V. UPDATE ON PROBLEMATIC LAWS................................................................25 VI. THE MYANMAR PRISON SYSTEM .................................................................30 Continuing humanitarian concerns ..........................................................................31 VII. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................34 -

The Role of Students in the 8888 Peoples Uprising in Burma

P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand e.mail: [email protected] website: www.aappb.org ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Twenty three years ago today, on 8 August 1988, hundreds of thousands of people flooded the streets of Burma demanding an end to the suffocating military rule which had isolated and bankrupted the country since 1962. Their united cries for a transition to democracy shook the core of the country, bringing Burma to a crippling halt. Hope radiated throughout the country. Teashop owners replaced their store signs with signs of protest, dock workers left behind jobs to join the swelling crowds, and even some soldiers were reported to have been so moved by the demonstrations to lay down their arms and join the protestors. There was so much promise. Background The decision of over hundreds of thousands of Burmese to take to the streets on 8 August 1988 did not happen overnight, but grew out of a growing sense of political discontent and frustration with the regime’s mismanagement of the country’s financial policies that led to deepening poverty. In 1962 General Ne Win, Burma’s ruthless dictator for over twenty years, assumed power through a bloody coup. When students protested, Ne Win responded by abolishing student unions and dynamiting the student union building at Rangoon University, resulting in the death of over 100 university students. All unions were immediately outlawed, heavily restricting the basic civil rights of millions of people. This was the beginning of a consolidation of power by a military regime which would systematically wipe out all opposition groups, starting with student unions, using Ne Win’s spreading network of informers and military intelligence officers. -

The Massive Increase in Burma's Political Prisoners September 2008

The Future in the Dark: The Massive Increase in Burma’s Political Prisoners September 2008 Jointly Produced by: Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) and United States Campaign for Burma The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) (AAPP) is dedicated to provide aid to political prisoners in Burma and their family members. The AAPP also monitors and records the situation of all political prisoners and condition of prisons and reports to the international community. For further information about the AAPP, please visit to our website at www.aappb.org. The United States Campaign for Burma (USCB) is a U.S.-based membership organization dedicated to empowering grassroots activists around the world to bring about an end to the military dictatorship in Burma. Through public education, leadership development initiatives, conferences, and advocacy campaigns at local, national and international levels, USCB works to empower Americans and Burmese dissidents-in-exile to promote freedom, democracy, and human rights in Burma and raise awareness about the egregious human rights violations committed by Burma’s military regime. For further information about the USCB, please visit to our website at www.uscampaignforburma.org 1 Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand [email protected], www.aappb.org United States Campaign for Burma 1444 N Street, NW, Suite A2, Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 234 8022, Fax: (202) 234 8044 [email protected], www.uscampaignforburma.org -

11-Monthly Chronology of Burma Political Prisoners for November 2008

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for November 2008 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2164 political prisoners in Burma. These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 17 Students 271 Women 184 NLD members 472 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network 37 Ethnic nationalities 211 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 22 Teachers 25 Media activists 42 Lawyers 13 In poor health 106 Since the protests in August 2007, leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1057 activists have been arrested. Monthly trend analysis In the month of November, at least 215 250 political activists have been sentenced, 200 the majority of whom were arrested in 1 50 Arrested connection with last year’s popular Sentenced uprising in August and September. They 1 00 Released include 33 88 Generation Students Group 50 members, 65 National League for 0 Democracy members and 27 monks. Sep-08 Oct-08 Nov-08 The regime began trials of political prisoners arrested in connection with last year’s Saffron Revolution on 8 October last year. Since then, at least 384 activists have been sentenced, most of them in November this year. This month at least 215 activists were sentenced and 19 were arrested. This follows the monthly trend for October, when there were 45 sentenced and 18 arrested. The statistics confirm reports, which first emerged in October, that the regime has instructed its judiciary to expedite the trials of detained political activists. This month Burma’s flawed justice system has handed out severe sentences to leading political activists.