Social World Sensing Via Social Image Analysis from Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mercury(II) Heterobimetallic Complexes Using a Hybrid Ligand, 1, 2-Bis(Diphenylphosphino) Ethane Monoxide

37 Sciencia Acta Xaveriana Volume 5 An International Science Journal No. 1 ISSN. 0976-1152 pp. 37-46 March 2014 Synthesis of organotin(IV) - mercury(II) heterobimetallic complexes using a hybrid ligand, 1, 2-bis(diphenylphosphino) ethane monoxide E. M. Mothia* and K. Panchantheswaranb a Department of Chemistry, Saveetha School of Engineering, Saveetha University, Thandalam, Chennai 602 105, India b School of Chemistry, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli 620 024, India *Email : [email protected] Abstract : The reaction of 1, 2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane monoxide, a hybrid ligand containing both soft (P) and hard (O) Lewis base centers in the same molecule, with organotin(IV) chloride and mercury(II) chloride has been carried out using dichloromethane as solvent. The products [HgCl2.(dppeO).R2SnCl2]n [R = Me (1), Ph (2) and CH2Ph (3)] have been obtained in excellent yields and are characterized using IR, 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopic methods. Based on the spectral data it is proposed that the structure may contain -Hg-P-O-Sn-O-P- Hg- polymeric array. Keywords : hybrid ligands, organotin, mercury, phosphine, phosphine oxide (Received : January 2014, Accepted February 2014) 38 Synthesis of organotin(IV) - mercury(II) heterobimetallic complexes using a hybrid ligand 1. Introduction Hybrid ligands are polydentate ligands that contain at least two different types of chemical functionality capable of binding to metal centers. These functionalities are often chosen to be very different from each other to increase the difference between their resulting interactions with metal centers and thereby contribute to chemoselectivity. Combining hard and soft donors in the same ligand has marked the evolution of different and contrasting chemistries, thus leading to novel and unprecedented properties for the resulting metal complexes.1An important class of such hybrid ligands are bis-phosphine monoxides (BPMOs) of the general formula R1R2P-Y-P(O)R3R4, where Y is a divalent spacer. -

BLUE HEN CHEMIST University of Delaware, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Annual Alumni Newsletter Number 41 August 2014 John L

BLUE HEN CHEMIST University of Delaware, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Annual Alumni Newsletter NUMBER 41 AUGUST 2014 JOHN L. BURMEISTER, EDITOR ON THE COVER THREE Newly Renovated Organic Laboratories! # 3 8 - P AGE I BLU E H E N C H E MIST ON THE COVER One of the three newly-renovated Organic Chemistry teaching laboratories (QDH 302) is shown. Work on the labs (QDH 112, 318, 320) started on May, 2013 and was completed in February of this year. The refurbishment of the labs was a crucial step in the ongoing revision of the Organic Chemistry laboratory curricula. The additional fume hoods allow each student to conduct experiments individually while minimizing their exposure to chemical reagents. The transparent glass construction helps teaching assistants observe students while they work. The hoods are equipped with inert-gas lines, which can allow the students to work with air-sensitive compounds and learn advanced laboratory techniques. The hoods are also equipped with vacuum lines, which obviate the need for water aspirators and dramatically reduce the labs' water usage. The lab design also allows for instrumentation modules to be swapped in and out according to the needs of the experiment. Carts are designed to house instruments such as gas chromatographs and infrared spectrometers as well as any necessary computer equipment. These carts can then be wheeled into docking areas that have been fitted with the necessary inert gas and electrical lines. The design expands the range of possible instrumentation the students can use while occupying a small footprint of lab space. The labs also feature large flat screen monitors, wireless internet, and computer connectivitiy that will enable the use of multimedia demonstrations and tablet computing. -

DUPONT DATA BOOK SCIENCE-BASED SOLUTIONS Dupont Investor Relations Contents 1 Dupont Overview

DUPONT DATA BOOK SCIENCE-BASED SOLUTIONS DuPont Investor Relations Contents 1 DuPont Overview 2 Corporate Financial Data Consolidated Income Statements Greg Friedman Tim Johnson Jennifer Driscoll Consolidated Balance Sheets Vice President Director Director Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows (302) 999-5504 (515) 535-2177 (302) 999-5510 6 DuPont Science & Technology 8 Business Segments Agriculture Electronics & Communications Industrial Biosciences Nutrition & Health Performance Materials Ann Giancristoforo Pat Esham Manager Specialist Safety & Protection (302) 999-5511 (302) 999-5513 20 Corporate Financial Data Segment Information The DuPont Data Book has been prepared to assist financial analysts, portfolio managers and others in Selected Additional Data understanding and evaluating the company. This book presents graphics, tabular and other statistical data about the consolidated company and its business segments. Inside Back Cover Forward-Looking Statements Board of Directors and This Data Book contains forward-looking statements which may be identified by their use of words like “plans,” “expects,” “will,” “believes,” “intends,” “estimates,” “anticipates” or other words of similar meaning. All DuPont Senior Leadership statements that address expectations or projections about the future, including statements about the company’s strategy for growth, product development, regulatory approval, market position, anticipated benefits of recent acquisitions, timing of anticipated benefits from restructuring actions, outcome of contingencies, such as litigation and environmental matters, expenditures and financial results, are forward looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are based on certain assumptions and expectations of future events which may not be realized. Forward-looking statements also involve risks and uncertainties, many of which are beyond the company’s control. -

Outgassing of Technical Polymers PEEK, Kapton, Vespel & Mylar

Ivo Wevers Outgassing of Technical Polymers PEEK, Kapton, Vespel & Mylar Vacuum, Surfaces & Coatings Group Technology Department Outline • Part 1: Introduction • Polymers in vacuum technology • Outgassing of water : metallic surface vs polymer • Part 2: Outgassing at Room Temperature • Outgassing measurements of PEEK, Kapton, Mylar and Vespel samples • Fitting with 2-step and 3-step models • Diffusion coefficient, moisture content and decay time constant • Part 3: Attenuation of Polymers Outgassing • Effects of bakeout and venting on pump-down curves • Effects of desication with silica gel • Conclusions & Future Vacuum, Surfaces & Coatings Group Ivo Wevers ARIES 2021 Technology Department 2 Part 1: Introduction • Polymers in vacuum technology • Outgassing of water : metallic surface vs polymer Vacuum, Surfaces & Coatings Group Ivo Wevers ARIES 2021 Technology Department 3 Polymers in vacuum technology Polymers are sometimes the only option as seal/insulator PEEK, Kapton and Vespel -> bakeout temperatures of 150-200C° Vacuum, Surfaces & Coatings Group Ivo Wevers ARIES 2021 Technology Department 4 Polymers in vacuum technology Polymers are sometimes the only option as seal/insulator PEEK, Kapton and Vespel -> bakeout temperatures of 150-200C° Guarantee a certain beam lifetime or certain operation conditions Outgassing limit (maximum pressure to be reached in 24 hours) is defined for each machine AND the residual gas analysis free of contaminants Acceptance test prior to installation: - Pumpdown will define the outgassing rate and variation -

Plasticulture in California Vegetable Production

PUBLICATION 8016 Plasticulture in California Vegetable Production WAYNE L. SCHRADER, UC Cooperative Extension Vegetable Farm Advisor, San Diego County Plasticulture is the art of using plastic materials to modify the production environ- UNIVERSITY OF ment in vegetable crop production. Plasticulture began in the 1950s and early 1960s with the introduction and use of plastic films, mulches, and drip irrigation systems. CALIFORNIA Vegetable growers frequently use plastics in pest management, stand establishment, Division of Agriculture harvesting, and postharvest handling operations, and in containers for marketing. and Natural Resources Plasticulture system components can include http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu • plastic mulches to control soil temperature, control weeds, and repel insects • plastic films for erosion control, soil fumigation, or solarization • row covers for temperature control, wind or frost protection, and insect exclusion • drip irrigation for improved water management and for the application of chemi- cals (chemigation) and fertilizers (fertigation) during irrigation • plastic windbreaks • plastic barriers against vertebrate pests Plasticulture has developed into management systems that allow growers to achieve higher-quality produce, superior yields, and extended production cycles. Growers using plasticulture can produce vegetables for markets during the winter, early spring, and late fall that would otherwise be impossible to address. Benefits of plasticulture include • earlier production (7 to 30 days earlier) • increased -

CO2 Derivatives of Molecular Tin Compounds. Part 1: † Hemicarbonato and Carbonato Complexes

inorganics Review CO2 Derivatives of Molecular Tin Compounds. Part 1: y Hemicarbonato and Carbonato Complexes Laurent Plasseraud Institut de Chimie Moléculaire de l’Université de Bourgogne (ICMUB), UMR-CNRS 6302, Université de Bourgogne Franche-Comté, 9 avenue A. Savary, F-21078 Dijon, France; [email protected] Paper dedicated to Professor Georg Süss-Fink on the occasion of his 70th birthday. y Received: 31 March 2020; Accepted: 24 April 2020; Published: 29 April 2020 Abstract: This review focuses on organotin compounds bearing hemicarbonate and carbonate ligands, and whose molecular structures have been previously resolved by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Most of them were isolated within the framework of studies devoted to the reactivity of tin precursors with carbon dioxide at atmospheric or elevated pressure. Alternatively, and essentially for the preparation of some carbonato derivatives, inorganic carbonate salts such as K2CO3, Cs2CO3, Na2CO3 and NaHCO3 were also used as coreagents. In terms of the number of X-ray structures, carbonate compounds are the most widely represented (to date, there are 23 depositions in the Cambridge Structural Database), while hemicarbonate derivatives are rarer; only three have so far been characterized in the solid-state, and exclusively for diorganotin complexes. For each compound, the synthesis conditions are first specified. Structural aspects involving, in particular, the modes of coordination of the hemicarbonato and carbonato moieties and the coordination geometry around tin are then described and illustrated (for most cases) by showing molecular representations. Moreover, when they were available in the original reports, some characteristic spectroscopic data are also given for comparison (in table form). -

Synthesis and Kinetics of Novel Ionic Liquid Soluble Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reagents

Synthesis and kinetics of novel ionic liquid soluble hydrogen atom transfer reagents Thomas William Garrard Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 School of Chemistry The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper ORCID: 0000-0002-2987-0937 Abstract The use of radical methodologies has been greatly developed in the last 50 years, and in an effort to continue this progress, the reactivity of radical reactions in greener alternative solvents is desired. The work herein describes the synthesis of novel hydrogen atom transfer reagents for use in radical chemistry, along with a comparison of rate constants and Arrhenius parameters. Two tertiary thiol-based hydrogen atom transfer reagents, 3-(6-mercapto-6-methylheptyl)-1,2- dimethyl-3H-imidazolium tetrafluoroborate and 2-methyl-7-(2-methylimidazol-1-yl)heptane-2-thiol, have been synthesised. These are modelled on traditional thiol reagents, with a six-carbon chain with an imidazole ring on one end and tertiary thiol on the other. 3-(6-mercapto-6-methylheptyl)- 1,2-dimethyl-3H-imidazolium tetrafluoroborate comprises of a charged imidazolium ring, while 2- methyl-7-(2-methylimidazol-1-yl)heptane-2-thiol has an uncharged imidazole ring in order to probe the impact of salt formation on radical kinetics. The key step in the synthesis was addition of thioacetic acid across an alkene to generate a tertiary thioester, before deprotection with either LiAlH4 or aqueous NH3. Arrhenius plots were generated to give information on rate constants for H-atom transfer to a primary alkyl radical, the 5-hexenyl radical, in ethylmethylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide. -

Space Environment Exposure Results from the Misse 5 Polymer Film Thermal Control Experiment on the International Space Station

SPACE ENVIRONMENT EXPOSURE RESULTS FROM THE MISSE 5 POLYMER FILM THERMAL CONTROL EXPERIMENT ON THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION Sharon K.R. Miller(1), Joyce A. Dever(2) (1)NASA Glenn Research Center, 21000 Brookpark Rd. MS 309-2, Cleveland, OH, 44135, U.S.A., Phone: 1-216-433- 2219, E-mail: [email protected] (2)NASA Glenn Research Center, 21000 Brookpark Rd. MS 106-1, Cleveland, OH, 44135, U.S.A., Phone: 1-216-433- 6294, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Station Experiment (MISSE) 1, was designed to expose tensile specimens of a small selection of polymer films It is known that polymer films can degrade in space on ram facing and non-ram facing surfaces of MISSE 1 due to exposure to the environment, but the magnitude [2]. A more complete description of the NASA Glenn of the mechanical property degradation and the degree Resarch Center MISSE 1-7 experiments is contained in to which the different environmental factors play a role a publication by Kim de Groh et al [3]. The PFTC was in it is not well understood. This paper describes the expanded and flown as one of the experiments on the results of an experiment flown on the Materials nadir facing side of MISSE 5 in order to examine the International Space Station Experiment (MISSE) 5 to long term effects of the space environment on the determine the change in tensile strength and % mechanical properties of a wider variety of typical elongation of some typical polymer films exposed in a spacecraft polymers exposed to the anti-solar or nadir nadir facing environment on the International Space facing space environment. -

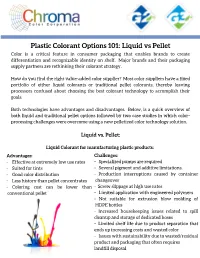

Liquid Vs Pellet Color Is a Critical Feature in Consumer Packaging That Enables Brands to Create Differentiation and Recognizable Identity on Shelf

Plastic Colorant Options 101: Liquid vs Pellet Color is a critical feature in consumer packaging that enables brands to create differentiation and recognizable identity on shelf. Major brands and their packaging supply partners are rethinking their colorant strategy. How do you find the right value-added color supplier? Most color suppliers have a fixed portfolio of either liquid colorants or traditional pellet colorants, thereby leaving processors confused about choosing the best colorant technology to accomplish their goals. Both technologies have advantages and disadvantages. Below, is a quick overview of both liquid and traditional pellet options followed by two case studies in which color- processing challenges were overcome using a new pelletized color technology solution. Liquid vs. Pellet: Liquid Colorant for manufacturing plastic products: Ad vantages: Challenges: - Effective at extremely low use rates - Specialized pumps are required - Suited for tints - Several pigment and additive limitations. - Good color distribution - Production interruptions caused by container - Less history than pellet concentrates changeover - Coloring cost can be lower than - Screw slippage at high use rates conventional pellet - Limited application with engineered polymers - Not suitable for extrusion blow molding of HDPE bottles - Increased housekeeping issues related to spill cleanup and storage of dedicated hoses - Limited shelf life due to product separation that ends up increasing costs and wasted color - Issues with sustainability due to wasted/residual -

Exploring the Influence of Entropy on Dynamic Macromolecular Ligation

Exploring the Influence of Entropy on Dynamic Macromolecular Ligation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (Dr. rer. nat.) der KIT-Fakultät für Chemie und Biowissenschaften des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT) genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl.-Chem. Kai Pahnke aus Nagold, Deutschland KIT-Dekan: Prof. Dr. Willem M. Klopper Referent: Prof. Dr. Christopher Barner-Kowollik Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Manfred Wilhelm Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 22.07.2016 Die vorliegende Arbeite wurde im Zeitraum von Februar 2013 bis Juni 2016 im Rahmen einer Kollaboration zwischen dem KIT und der Evonik Industries AG unter der Betreuung von Prof. Dr. Christopher Barner-Kowollik durchgeführt Only entropy comes easy. Anton Chekhov ABSTRACT The present thesis reports a novel, expedient linker species as well as previously unforeseen effects of physical molecular parameters on reaction entropy and thus equilibria with extensive implications on diverse fields of research via the study of dynamic ligation chemistries, especially in the realm of macromolecular chemistry. A set of experiments investigating the influence of different physical molecular parameters on reaction or association equilibria is designed. Initially, previous findings of a mass dependant effect on the reaction entropy – resulting in a more pronounced debonding of heavier or longer species – are reproduced and expanded to other dynamic ligation techniques as well as further characterization methods, now including a rapid and catalyst- free Diels–Alder reaction. The effects are evidenced via high temperature nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (HT NMR) as well as temperature dependent size exclusion chromatography (TD SEC) and verified via quantum chemical ab initio calculations. Next, the impact of chain mobility on entropic reaction parameters and thus the overall bonding behavior is explored via the thermoreversible ligation of chains of similar mass and length, comprising isomeric butyl side-chain substituents with differing steric demands. -

DE-FOA-0001954 Modification 20

FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE FUNDING OPPORTUNITY ANNOUNCEMENT ADVANCED RESEARCH PROJECTS AGENCY – ENERGY (ARPA-E) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY SOLICITATION ON TOPICS INFORMING NEW PROGRAM AREAS SBIR/STTR Announcement Type: Modification 19 20 Funding Opportunity No. DE-FOA-0001954 CFDA Number 81.135 FOA Issue Date: December 20, 2018 FOA Close Date: Open continuously until otherwise amended. Application Due Date: See Targeted Topics Table for topic-specific application due dates. Total Amount to Be Awarded Approximately $114.75 million, subject to the availability of appropriated funds to be shared between FOAs DE-FOA-0001953 and DE-FOA-0001954. See Targeted Topics Table for topic-specific information. Anticipated Awards ARPA-E may issue one, multiple, or no awards under this FOA. Awards may vary between $100,000 and $3,721,115 . See Targeted Topics Table for topic-specific award amount requirements. • For eligibility criteria, see Section III.A – III.D of the FOA. • For cost share requirements under this FOA, see Section III.E of the FOA. • To apply to this FOA, Applicants must register with and submit application materials through ARPA-E eXCHANGE (https://arpa-e-foa.energy.gov/Registration.aspx). For detailed guidance on using ARPA-E eXCHANGE, see Section IV.F.1 of the FOA. • Applicants are responsible for meeting the submission deadline associated with each Targeted Topic. Applicants are strongly encouraged to submit their applications at least 48 hours in advance of the Targeted Topic submission deadline. • For detailed guidance on compliance and responsiveness criteria, see Sections III.F.1 through III.F.3 of the FOA. Questions about this FOA? Check the Frequently Asked Questions available at http://arpa-e.energy.gov/faq . -

Checking out on Plastics III

Checking Out on Plastics III January 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABOUT EIA ABOUT GREENPEACE EIA UK CONTENTS 62-63 Upper Street, With support from John Ellerman We investigate and campaign against Greenpeace defends the natural Executive Summary 4 London N1 0NY UK Foundation. environmental crime and abuse. world and promotes peace by Introduction 6 T: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 investigating, exposing and Background 7 “We aim to advance the wellbeing Our undercover investigations E: [email protected] confronting environmental abuse Methodology 8 of people, society and the natural expose transnational wildlife crime, eia-international.org and championing responsible Summary of results 10 world by focusing on the arts, with a focus on elephants and solutions for our fragile Targets 12 environment and social action. tigers, and forest crimes such as Environmental Investigation Agency UK environment. The plastic packaging footprint 13 We believe these areas can make illegal logging and deforestation for UK Charity Number: 1182208 Own-brand versus branded reductions 14 an important contribution to cash crops like palm oil. We work to Company Number: 07752350 Overall trends in this year’s survey 16 wellbeing.” safeguard global marine ecosystems Registered in England and Wales Retailer snapshot: highlights and lowlights 18 by addressing the threats posed Plastic bags 20 by plastic pollution, bycatch Single-use items 24 and commercial exploitation of Fruit and vegetables 28 whales, dolphins and porpoises. Reuse and refill 30 Finally, we reduce the impact of Recycling and recycled content 32 climate change by campaigning Online 33 to eliminate powerful refrigerant Convenience retailers 34 greenhouse gases, exposing related Conclusions 35 illicit trade and improving energy Recommendations 36 efficiency in the cooling sector.