Usaid Grid-Scale Energy Storage Technologies Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles

Article Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles Efstathios E. Michaelides Department of Engineering, TCU, Fort Worth, TX 76132, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The global market of electric vehicles has become one of the prime growth industries of the 21st century fueled by marketing efforts, which frequently assert that electric vehicles are “very efficient” and “produce no pollution.” This article uses thermodynamic analysis to determine the primary energy needs for the propulsion of electric vehicles and applies the energy/exergy trade-offs between hydrocarbons and electricity propulsion of road vehicles. The well-to-wheels efficiency of electric vehicles is comparable to that of vehicles with internal combustion engines. Heat transfer to or from the cabin of the vehicle is calculated to determine the additional energy for heating and air-conditioning needs, which must be supplied by the battery, and the reduction of the range of the vehicle. The article also determines the advantages of using fleets of electric vehicles to offset the problems of the “duck curve” that are caused by the higher utilization of wind and solar energy sources. The effects of the substitution of internal combustion road vehicles with electric vehicles on carbon dioxide emission avoidance are also examined for several national electricity grids. It is determined that grids, which use a high fraction of coal as their primary energy source, will actually increase the carbon dioxide emissions; while grids that use a high fraction of renewables and nuclear energy will significantly decrease their carbon dioxide emissions. Globally, the carbon dioxide emissions will decrease by approximately 16% with the introduction of electric vehicles. -

Flywheel Energy Storage

Energy and the Environment Capstone Design Project { Bass Connections 2017 Flywheel Energy Storage (FES): Exploring Alternative Use Cases Randy Frank, Mechanical Engineering '17 Jessica Matthys, Mechanical Engineering '17 Caroline Ayanian, Mechanical Engineering '17 Daniel Herron, Civil and Environmental Engineering '17 Nathaniel Sizemore, Public Policy '17 Cameron Simpson, Economics '17 Dante Cordaro, Economics '18 Jack Carey, Environmental Science and Policy '17 Spring 2017 Contents 1 Abstract 3 2 Introduction 3 2.1 Energy Markets............................................3 3 Concept Generation 6 3.1 Traditional Energy Storage Methods................................6 3.2 Decision Matrix............................................7 4 Technology Background 8 4.1 Flywheel Past and Present......................................8 4.2 Flywheel Energy Storage Fundamentals..............................8 4.3 Limiting Factors to FES Storage Capacity.............................9 4.4 Additional Mechanical Components................................ 10 4.5 Electrical Components........................................ 14 5 Prototype Design 14 5.1 Prototype Overview and Goals................................... 14 5.2 Bill of Materials........................................... 15 5.3 Material Selection.......................................... 15 5.4 Motor Selection............................................ 15 5.5 Timeline................................................ 17 5.6 Prototype Assembly......................................... 17 5.7 Prototype -

Energy Storage Technology Assessment Prepared for Public Service Company of New Mexico

Energy Storage Technology Assessment Prepared for Public Service Company of New Mexico HDR Report No. 10060535-0ZP-C1001 Revision B - Draft October 30, 2017 Principal Investigators Todd Aquino, PE Chris Zuelch, PE Cristina Koss Publi c Service Company of New Mexico | Energy Storage Technology Assessment Table of Contents I. Scope .................................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Introduction / Purpose ........................................................................................................................ 3 III. The Need for Energy Storage ............................................................................................................... 6 V. Energy Storage Technologies ............................................................................................................... 7 VI. Battery Storage Technologies .............................................................................................................. 7 Lithium Ion Battery ................................................................................................................................. 13 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 13 Maturity .............................................................................................................................................. 13 Technological Characteristics -

Thermal Storage Impact on CHP Cogeneration Performance with Southwoods Case Study Edmonton, Alberta Michael Roppelt C.E.T

Thermal Storage Impact on CHP Cogeneration Performance with Southwoods Case Study Edmonton, Alberta Michael Roppelt C.E.T. CHP Cogeneration Solar PV Solar Thermal Grid Supply Thermal Storage GeoExchange RenewableAlternative & LowEnergy Carbon Microgrid Hybrid ConventionalSystemSystem System Optional Solar Thermal Option al Solar PV CNG & BUILDING OR Refueling COMMUNITY Station CHP Cogeneration SCALE 8 DEVELOPMENT Hot Water Hot Water DHW Space Heating $ SAVINGS GHG OPERATING Thermal Energy Cool Water Exchange & Storage ElectricalMicro Micro-Grid-Grid Thermal Microgrid Moving Energy not Wasting Energy Natural Gas Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Cogeneration $350,000 2,500,000 kWh RETAILINPUT OUTPUT VALUE NATURAL GAS $400,000. $100,000.30,000 Gj (85% Efficiency) CHP $50,000 Cogeneration15,000 Energy Gj Technologies CHP Unit Sizing Poorly sized units will not perform optimally which will cancel out the benefits. • For optimal efficiency, CHP units should be designed to provide baseline electrical or thermal output. • A plant needs to operate as many hours as possible, since idle plants produce no benefits. • CHP units have the ability to modulate, or change their output in order to meet fluctuating demand. Meeting Electric Power Demand Energy Production Profile 700 Hourly Average 600 353 January 342 February 500 333 March 324 April 400 345 May 300 369 June 400 July 200 402 August 348 September 100 358 October 0 362 November 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Meeting Heat Demand with CHP Cogeneration Energy Production Profile Heat Demand (kWh) Electric Demand (kWh) Cogen Heat (kWh) Waste Heat Heat Shortfall Useable Heat CHP Performance INEFFICIENCY 15% SPACE HEATING DAILY AND HEAT 35% SEASONAL ELECTRICAL 50% IMBALANCE 35% 50% DHW 15% Industry Studies The IEA works to ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its 30 member countries and beyond. -

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

Electric Battery Car Competition Rules

Colorado Middle School Car Competition Electric Battery Division The Colorado Middle School Car Competition is a classroom-based, hands-on educational program for 6th – 8th grade students. Student teams apply math, science, and creativity to construct and race model lithium-ion powered cars. The primary goals of the programs are to: • Generate enthusiasm for science and engineering at a crucial stage in the educational development of young people; • Improve students' understanding of scientific concepts and renewable energy technologies; and • Encourage young people to consider technical careers at an early age. Program description: • Students use mathematics and science principles together with their creativity in a fun, hands-on educational program. • Using engineering principles, students get excited about generating ideas in a group and then building and modifying models based on these ideas. • Students can see for themselves how changes in design are reflected in car performance. • Students work together on teams to apply problem solving and project management skills. The car competition challenges students to use scientific know-how, creative thinking, experimentation, and teamwork to design and build high-performance model electric battery vehicles. Rules Competition Structure: The Colorado competition will use preliminary time trials before progressing to a double elimination tournament for the finals. Each team will have three time trials to achieve their fastest time. Any car that does not finish in 40 seconds will be considered a Did Not Finish (DNF). Only the fastest 16 teams will progress to the double elimination tournament. In the event of a tie, teams will have a race-off to qualify for the double elimination round. -

Modeling, Testing and Economic Analysis of Wind-Electric Battery

NREL/CP-500-24920 · UC Category: 1213 Modeling, Testing and Economic Analysis of a Wind-Electric Battery Charging Station Vahan Gevorgian, David A. Corbus, Stephen Drouilhet, Richard Holz National Renewable Energy Laboratory Karen E. Thomas University of California at Berkeley Presented at Windpower '98 Bakersfield, CA April 27-May 1, 1998 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 A national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Managed by Midwest Research Institute for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC36-83CH10093 Work performed under task number WE802230 July 1998 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercialproduct, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authord expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available to DOE and DOE contractors from: Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI) P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Prices available by calling (423) 576-8401 Available to the public from: National Technical Information Service (NTIS) U.S. -

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean

Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean Raffaele Ferrari January 12, 2009 1 Energetics of a Turbulent Ocean One of the earliest theoretical investigations of ocean circulation was by Count Rumford. He proposed that the meridional overturning circulation was driven by temperature gradients. The ocean cools at the poles and is heated in the tropics, so Rumford speculated that large scale convection was responsible for the ocean currents. This idea was the precursor of the thermohaline circulation, which postulates that the evaporation of water and the subsequent increase in salinity also helps drive the circulation. These theories compare the oceans to a heat engine whose energy is derived from solar radiation through some convective process. In the 1800s James Croll noted that the currents in the Atlantic ocean had a tendency to be in the same direction as the prevailing winds. For example the trade winds blow westward across the mid-Atlantic and drive the Gulf Stream. Croll believed that the surface winds were responsible for mechanically driving the ocean currents, in contrast to convection. Although both Croll and Rumford used simple theories of fluid dynamics to develop their ideas, important qualitative features of their work are present in modern theories of ocean circulation. Modern physical oceanography has developed a far more sophisticated picture of the physics of ocean circulation, and modern theories include the effects of phenomena on a wide range of length scales. Scientists are interested in understanding the forces governing the ocean circulation, and one way to do this is to derive energy constraints on the differ- ent processes in the ocean. -

NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards, Release 1.0

NIST Special Publication 1108 NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards, Release 1.0 Office of the National Coordinator for Smart Grid Interoperability NIST Special Publication 1108 NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards, Release 1.0 Office of the National Coordinator for Smart Grid Interoperability January 2010 U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Director Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 7 1 Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................. 13 1.1 Overview and Background............................................................................................. 13 1.2 How This Report Was Produced.................................................................................... 16 1.3 Key Concepts ................................................................................................................. 18 1.3.1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 19 1.3.2 Applications and Requirements: Eight Priority Areas............................................ 20 1.4 Content Overview .......................................................................................................... 21 2 Smart Grid Vision.................................................................................................................. -

A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage

sustainability Review A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage Ioan Sarbu * ID and Calin Sebarchievici Department of Building Services Engineering, Polytechnic University of Timisoara, Piata Victoriei, No. 2A, 300006 Timisoara, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-256-403-991; Fax: +40-256-403-987 Received: 7 December 2017; Accepted: 10 January 2018; Published: 14 January 2018 Abstract: Thermal energy storage (TES) is a technology that stocks thermal energy by heating or cooling a storage medium so that the stored energy can be used at a later time for heating and cooling applications and power generation. TES systems are used particularly in buildings and in industrial processes. This paper is focused on TES technologies that provide a way of valorizing solar heat and reducing the energy demand of buildings. The principles of several energy storage methods and calculation of storage capacities are described. Sensible heat storage technologies, including water tank, underground, and packed-bed storage methods, are briefly reviewed. Additionally, latent-heat storage systems associated with phase-change materials for use in solar heating/cooling of buildings, solar water heating, heat-pump systems, and concentrating solar power plants as well as thermo-chemical storage are discussed. Finally, cool thermal energy storage is also briefly reviewed and outstanding information on the performance and costs of TES systems are included. Keywords: storage system; phase-change materials; chemical storage; cold storage; performance 1. Introduction Recent projections predict that the primary energy consumption will rise by 48% in 2040 [1]. On the other hand, the depletion of fossil resources in addition to their negative impact on the environment has accelerated the shift toward sustainable energy sources. -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

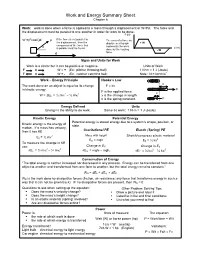

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process.