Open Jpatonmathesis Finalversion.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISF Fall 2009.Indd

English/Español Sommaire français en pages 13 et 14 September - December 2009 Volume 37 Number 3 Official Official Publication of the International Softball Federation Show your support for the Olympic reinstatement campaign. Visit the Back Softball website for more information and click on the merchandise link to help the drive to 2016 at www.BackSoftball.com An Initiative Of INTERNATIONAL SOFTBALL FEDERATION 1900 So. Park Road • Plant City, FL 33563 USA Telephone: (+1.813) 864.0100 • Fax: (+1.813) 864.0105 President’s Message Published at the Secretariat of the International Softball Federation Executive Council President Don E. Porter Secretary General Andrew S. Loechner, Jr. uly, August, and September were big and important months for softball First Vice President Clovis M. Lodewijks with many regional and world competitions being played and, in conclusion, all were successful. Deputy Secretary General Ms. Low Beng Choo J Vice Presidents Not only the competitive side has been successful but the sport’s Africa Marumo Morule development continues to make inroads into many countries with new Asia Steven S. W. Huang national federations being formed and active competitions being started. Masanori Ozaki Europe Mrs. Jelena Cusak Mike Jennings While the sport continues its efforts in development it will also continue Latin America Dr. Fernando Jorge Aren to work to bring back Olympic recognition, which to-date has seen four Jesús Suniaga Olympiads where overall softball was successful in giving Olympic dreams North America Dale McMann and opportunities to numerous young athletes. Oceania Bob Leveloff Council Members at Large Beatrice Allen Annie Constantinides As softball continues to expand on a global basis it will take more effort Meliton Sanchez and work by member federations and the International Softball Federation Ms. -

Annual R Eport 2013

2014 Under 19 Women’s National Champions 2013 - 2014 Report Annual Annual ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 14 O FFICE B EARERS C ONTENTS PATRON ARTICLE PAGE # The Honourable Campbell Newman MP Office Bearers 1 Premier of Queensland Strategic Plan 2 PRESIDENT President’s Message 3 Mark Jeppesen Sponsors & Supporters 4 Year In Review 5 VICE PRESIDENT Associate Members 8 Jenny Vandenhurk Recruitment 10 EXECUTIVE MEMBER Swing Into Softball 11 Stephen Wagner OzPitch 12 Kumbia Centenary 13 BOARD OF MANAGEMENT Steve Armitage Marketing 14 John Bright Awards & Recognition 15 Heather Law OAM Honour Role 16 Samantha Mathers (until 06/07/2013) Committees & Affiliates 17 Alicia Northcott (from (06/07/2013) High Performance Committee & 18 Coaching Technical Directorate STATE TECHNICAL DIRECTORS/CHAIR Lexie Pearce - Coaching Scoring Technical Directorate 20 Matt Denkel - Scoring Umpiring Technical Directorate 22 Darren Sibraa - Umpiring State Championship Results 26 State Team Lists & Results 30 ADMINISTRATION STAFF Australian Representation 36 Sue Nisbet - General Manager QLD School Sport Softball 38 Joan Jackson - Finance Manager Southern Cross Challenge 37 Nicole Watts - Operations Manager (on leave from 31/01/2014) SQ Masters Tournament 40 Nicki Riley - Events Co-Ordinator Participation Analysis - 2013/14 43 John Butterworth - Development Officer Finance Report 44 Karen Robe - Association Co-Ordinator District Associations Reports 54 Joy Leach - Database Manager Fabian Barlow - Elite Program Head Coach Kelsey Naylor - Administration Officer (contract from 15/01/2014) CONTACT DETAILS Softball Queensland Inc. Sports House South 1/866 Main Street Woolloongabba Q 4102 Phone: (07) 3391 2447 Fax: (07) 3391 4734 Email: [email protected] Website: www.qld.softball.org.au 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 14 S TRATEGIC P LAN VISION KEY PERFORMANCE AREAS To grow softball in Queensland as a sport for everyone’s enjoyment. -

City Water Funds Probe Hits Home

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U WEATHER, A2 • TRIBUTES, A5 • WORLD, A8 • CLASSIFIEDS, B5 • SOCIETY, C2 • PUZZLES & TV, C3 JUNIORS SHISHINE AT SALEM HILLS BRIDGE TO SUCCESS KIDMAN ‘BEGUILED’ Several more qualify for tournament City schools’ program targets freshmen New fi lm puts female spin on Civil War SPORTS | B1 LOCAL | A3 VALLEY LIFE | C1 8 M D ORE RVE THA S SE N 14,000 VALLEY GOLFER FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 U 75¢ City, arena, TRUMP, PUTIN AT G20 YSU work CITY WATER FUNDS to lessen Trump Putin parking PROBE HITS HOME Anxiety, hassles hope run By DAVID SKOLNICK [email protected] YOUNGSTOWN With numerous events this high for weekend downtown and at Youngstown State Univer- sity – attracting thousands of people with some main roads meeting either closed or restricted to vehicular traffic – finding Associated Press parking could prove to be a MOSCOW bit challenging. For Russian President Vladimir Pu- But event coordinators tin, a meeting with U.S. counterpart and city officials are trying Donald Trump on to ease the potential parking the sidelines of the problems people may find Group of 20 sum- INSIDE coming to various festivals mit in Germany U President and other special events. offers a long- Trump waffl es After 4 p.m. today until 8 sought opportu- on Russian med- a.m. Monday, all on-street nity to negotiate dling. A2 parking in the downtown a rapprochement area is free, said Michael with Washington. McGiffin, the city’s direc- But controversy tor of downtown events and over the Trump campaign’s ties with citywide special projects. -

Usssa Fastpitch Rule Book

OFFICIAL FASTPITCH PLAYING RULES and BY-LAWS Fourteenth Edition USSSA, LLC 611 Line Dr Kissimmee, FL 34744 (800) 741-3014 www.usssa.com USSSA National Offices will relocate April 17, 2017: USSSA, LLC 5800 Stadium Parkway Viera, FL 32940 (800) 741-3014 www.usssa.com 14th Edition (2-18 Online revision) 1 USSSA FASTPITCH RULES & BY-LAWS FOURTEENTH EDITION Table of Contents Classifications and Age Requirements ................................................................................4 Changes in Fourteenth Edition Playing Rules ....................................................................5 USSSA Official Fastpitch Playing Rules FOURTEENTH EDITION .............................6 RULE 1. PLAYING FIELD ................................................................................................6 RULE 2. EQUIPMENT ......................................................................................................8 RULE 3. DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................16 RULE 4. THE GAME .......................................................................................................25 RULE 5. PLAYERS AND SUBSTITUTES ....................................................................28 RULE 6. PITCHING RULE .............................................................................................33 RULE 7. BATTING ...........................................................................................................37 RULE 8. BASE RUNNING ..............................................................................................40 -

OHSAA Handbook for Match Type)

2021-22 Handbook for Member Schools Grades 7 to 12 CONTENTS About the OHSAA ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 Who to Contact at the OHSAA ...........................................................................................................................................................5 OHSAA Board of Directors .................................................................................................................................................................6 OHSAA Staff .......................................................................................................................................................................................7 OHSAA Board of Directors, Staff and District Athletic Boards Listing .............................................................................................8 OHSAA Association Districts ...........................................................................................................................................................10 OHSAA Affiliated Associations ........................................................................................................................................................11 Coaches Associations’ Proposals Timelines ......................................................................................................................................11 2021-22 OHSAA Ready Reference -

NFHS Guidance for Opening up High School Athletics and Activities

GUIDANCE FOR OPENING UP HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETICS AND ACTIVITIES National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) Sports Medicine Advisory Committee (SMAC) The COVID-19 pandemic presents state high school associations with a myriad of challenges. The NFHS Sports Medicine Advisory Committee (SMAC) offers this document as guidance on how state associations can consider approaching the many components of “opening up” high school athletics and activities across the United States. The NFHS SMAC believes it is essential to the physical and mental well-being of high school students across the nation to return to physical activity and athletic competition. The NFHS SMAC recognizes that it is likely that ALL students will not be able to return to – and sustain – athletic activity at the same time in all schools, regions and states. There will also likely be variation in what sports and activities are allowed to be played and held. While we would typically have reservations regarding such inequities, the NFHS SMAC endorses the idea of returning students to school-based athletics and activities in any and all situations where it can be done safely. Since NFHS member state associations are a well-respected voice for health and safety issues, the NFHS SMAC strongly urges that these organizations engage with state and local health departments to develop policy regarding coordinated approaches for return to activity for high school, club and youth sports. The recommendations presented in this document are intended as ideas for state associations to consider with their respective SMACs and other stakeholders in designing return-to-activity guidelines that will be in accordance with state or local restrictions. -

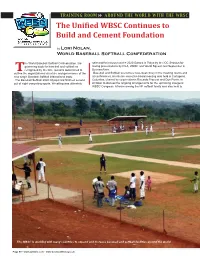

The Uni Ied WBSC Continues to Build And

TRAINING ROOM8 AROUND THE WORLD WITH THE WBSC The Uni�ied WBSC Continues to Build and Cement Foundation by Lori Nolan, World Baseball Softball Confederation he World Baseball Softball Confederation, the selected for inclusion at the 2020 Games in Tokyo by the IOC Session fol- governing body for baseball and softball as lowing presentations by FILA, WBSC and World Squash last September in Trecognized by the IOC, remains determined to Buenos Aires. outline the organizational structure and governance of the Baseball and Softball executives have been busy in the meeting rooms and new single Baseball Softball international body. at conferences. An interim executive board meeting was held in Cartagena, The Baseball Softball 2020 Olympic bid fi nished second Colombia, chaired by co-presidents Riccardo Fraccari and Don Porter, in out of eight competing sports. Wrestling was ultimately October to discuss the ongoing arrangements for the upcoming inaugural WBSC Congress. A forum among the NF softball family was also held to The WBSC is working with many countries to expand and increase baseball and softball facilities around the world. Page 90 • www.batwars.com • www.baseballthemag.com The WBSC continues to fi ght on behalf of the sports of softball Thomas Bach, IOC President and baseball for their reinstatement to the Olympic Games. update the membership on a wide variety of topics. The co-presidents and other offi cials in November were on-hand to participate in the SportAccord IF Forum in Lausanne, Switzerland. While there, the co-presidents took the op- portunity to meet with IOC sports director Christophe Dubi. -

Fastpitch Softball Coaching Kit

FASTPITCH SOFTBALL COACHING KIT www.slugger.com Dear Coach, It wasn’t that long ago that I was playing in youth leagues. I have fond memories of the fun I had and the friends I made on those fields. In fact, much of what I know about softball was learned in the youth leagues. And the most important part of my early softball education began with my youth league coaches. All of us on the Louisville Slugger Advisory Staff would like to thank you for your involvement in youth league softball and baseball. It may sound cliché, but it’s true: You will get just as much out of the experience as your kids will. The purpose of this Youth League Coaching Kit is to help you become a better coach. Inside, you’ll find a valuable playing guide with instructions on hitting, fielding, conducting practices and even dealing with your players’ parents. We’ve also included a chart to help you select the proper bat for your players. We’ve packed a wealth of softball knowledge into this year’s Youth League Coaching Kit. We hope you and your players will benefit greatly from this information. So take time now to thoroughly read this material before your team takes the field. Who knows, maybe a few years from now you’ll see one of your former players competing for a gold medal in the Olympics. Good luck on a fun and successful season! Sincerely, Jessica Mendoza U.S. Olympic Softball Team Member, Louisville Slugger Advisory Staff When conducting a practice, SUGGESTED it’s important to use your time PRACTICE efficiently. -

The Future of Rugby: an HSBC Report

The Future of Rugby: An HSBC Report #futureofrugby HSBC World Rugby Sevens Series 2015/16 VANCOUVER 12-13 March 2016 LONDON PARIS LANGFORD 21-22 May 2016 14-15 May 2016 16-17 April 2016 CLERMONT-FERRAND 28-29 May 2016 ATLANTA DUBAI 9-10 April 2016 LAS VEGAS 4-5 December 2016 4-6 March 2016 HONG KONG 8-10 April 2016 DUBAI 4-5 December 2016 SINGAPORE 16-17 April 2016 SÃO PAULO CAPE TOWN SYDNEY 20-21 February 2016 12-13 December 2016 6-7 February 2016 WELLINGTON KEY 29-30 January 2016 HSBC Men’s World Rugby Sevens Series HSBC Women’s World Rugby Sevens Series Catch all the latest from the HSBC World Rugby Sevens Series 2015/16 HSBC Sport 1985 1987 1993 1998 1999 2004 2009 2011 2016 International First Rugby First Rugby Rugby is World Rugby sevens The IOC Pan Rugby Rugby Board World Cup World Cup added to Sevens added to votes to American returns votes to set is hosted Sevens Common- Series World add rugby Games to the up Rugby jointly by wealth launched University to the includes Olympics World Cup Australia Games and Championships Olympics rugby and New Asian Games sevens Zealand The 30- year road to Rio 1991 1997 2004 2009 2010 2011 2015 2016 First First Women’s First Women’s First Women’s Women’s women’s women’s sevens at Women’s sevens Women’s sevens at sevens Rugby sevens World Sevens at Asian Sevens the Pan at the World Cup tournament University World Cup Games World American Olympics (fifteens) at Hong Championships Series Games Kong “The IOC [International Olympic Committee] is looking for sports that will attract a new fan base, new -

Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlight Shows, 1989-2009

GENDER IN TELEVISED SPORTS NEWS AND HIGHLIGHTS SHOWS, 1989‐2009 CO‐INVESTIGATORS Michael A. Messner, Ph.D. University of Southern California Cheryl Cooky, Ph.D. Purdue University RESEARCH ASSISTANT Robin Hextrum University of Southern California With an Introduction by Diana Nyad Center for Feminist Research, University of Southern California June, 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION by Diana Nyad…………………………………………………………………….………..3 II. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS…………………………………………………………………………………………4 III. DESCRIPTION OF STUDY…………………………………………………………………………………………6 IV. DESCRIPTION OF FINDINGS……………………………………………………………………………………8 1. Sports news: Coverage of women’s sports plummets 2. ESPN SportsCenter: A decline in coverage of women’s sports 3. Ticker Time: Women’s sports on the margins 4. Men’s “Big Three” sports are the central focus 5. Unequal coverage of women’s and men’s pro and college basketball 6. Shifting portrayals of women 7. Commentators: Racially diverse; Sex‐segregated V. ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF FINDINGS…………………………………………………….22 VI. REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………………..…………………28 VII. APPENDIX: SELECTED WOMEN’S SPORTING EVENTS DURING THE STUDY…………..30 VIII. BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE OF THE STUDY………………………………….…………….….33 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………………………….34 X. ABOUT THE CO‐INVESTIGATORS………………………………………………………………..….…….35 2 I. INTRODUCTION By Diana Nyad For two decades, the GENDER IN TELEVISED SPORTS report has tracked the progress— as well as the lack of progress—in the coverage of women’s sports on television news and highlights shows. One of the positive outcomes derived from past editions of this valuable study has been a notable improvement in the often‐derogatory ways that sports commentators used to routinely speak of women athletes. The good news in this report is that there is far less insulting and overtly sexist treatment of women athletes than there was twenty or even ten years ago. -

Joint Meeting Board & Parks and Recreation Foundation

PARKS & RECREATION BOARD AND PARKS & RECREATION FOUNDATION JOINT MEETING Tuesday, January 15, 2019 Regular Meeting 6:00 p.m. Cactus Yards – South Restaurant 4536 Elliot Road Gilbert, AZ 85234 Board Les Presmyk, Chair Gilbert Honeycutt Edward Madrid Members: Robert Ferron, Vice Chair Jennifer Jones Matthew Roberts Barbara Guy Mark LaPorte Christopher Warton Est. Time: Standing Agenda Items Staff Member: Board Action: 6:00 PM 1. Call to order Les Presmyk Report Only 2. Roll call Denise Merdon Report Only 3. Pledge of Allegiance Les Presmyk Report Only 4. Communication from citizens present * Les Presmyk Report Only Consent Items 5. None N/A N/A Presentations 6:10 PM 6. Gilbert Youth Sports Coalition Brent Taysom Report Only Annual Report 7. Parks Update Robert Carmona Report Only Standing Agenda Items 6:35 PM 8. IAP Update Rocky Brown Report; Discussion Agenda Items 6:45 PM 9. Parks and Recreation Foundation Parks and Recreation Discussion Board Members 10. Cactus Yards Dan Wilson Report; Discussion Opening Day Programming updates 11. Arizona Coyotes Follow-up Rocky Brown Report; Discussion Administrative Items 7:15 PM 12. Minutes-consider approval of the Board Members Discussion; possible minutes of the Parks and Recreation action by Motion meeting December 11, 2018 Communications 7:20 PM 13. Report from Chair Les Presmyk 14. Report from Board Members Board Members 15. Report from Council Liaison Vice Mayor Eddie Cook Report Only 16. Report from Staff Liaisons Staff Liaisons 17. Upcoming Special Events and Denise Merdon Volunteer Opportunities Conclusion 7:30 PM 18. Motion to adjourn the meeting Board Members Discussion; possible action by MOTION The next regular meeting is on February 12, 2019 at 6:00 p.m. -

2018 Ucla Softball Quick Facts 2018 Ucla Softball

2018 ROSTER AND Q UICK F ACTS 2018 UCLA SOFTBALL Q UICK F ACTS 2018 UCLA SOFTBALL R OSTER Location J.D. Morgan Center, NO NAME POS HT B/T YR EXP HOMETOWN (HIGH SCHOOL/LAST SCHOOL) 325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095 00 Rachel Garcia P 5-6 R/R R-SO 1V Palmdale, Calif. (Highland HS) Founded 1919 3 Briana Perez INF 5-7 L/R FR HS Martinez, Calif. (Alhambra HS) Enrollment 43,239 4 Holly Azevedo P 5-9 R/R FR HS San Jose, Calif. (Pioneer HS) 5 Julie Rodriguez OF 5-3 L/L FR HS Englewood, N.J. (Northern Valley Old Tappan HS) Nickname Bruins 7 Jenna Crawford OF 5-4 L/R SO 1V Pleasanton, Calif. (Foothill HS) Colors Blue and Gold 8 Kylee Perez INF 5-7 L/R SR 3V Martinez, Calif. (Alhambra HS) Conference Pac-12 10 Malia Quarles INF 5-5 R/R FR HS Cerritos, Calif. (Gahr HS) Chancellor Dr. Gene Block 11 Zia Norris OF 5-4 L/R FR HS Harbor City, Calif. (Bishop Montgomery HS) Athletic Director Dan Guerrero 12 Stevie Wisz OF 5-6 R/R JR 2V Orcutt, Calif. (Righetti HS) Senior Associate A.D./SWA Christina Rivera 13 Imani Johnson OF 5-1 L/R JR 2V Carson, Calif. (King/Drew Magnet HS) Faculty Athletic Representative Dr. Michael Teitell 15 Johanna Grauer P 5-6 R/R SR 3V Pleasanton, Calif. (Amador Valley HS) Home Field Easton Stadium 18 Selina Ta’amilo P 6-0 R/R SR 3V Murrieta, Calif.