Tolkien Anniversaries One Day Symposium, Wednesday, May 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 RECORD of PROCEEDINGS 7 Minutes of REGULAR Meeting

2014 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS 7 Minutes of REGULAR Meeting January 08, 2014 The Twinsburg City School District Board of Education met in REGULAR session on the above date at the Twinsburg Government Center in Council Chambers at 7:21 p.m. The following Board Members were present: Mrs. Cain-Criswell, Mrs. Davis, Mr. Felber, Mr. Stuver, and Mrs. Turle- Waldron. Recordings of the Board of Education meeting are made and kept at the Board Office. Video recordings and Board approved Minutes are available on the District’s web site. 14-035 Tax Budget Mr. Stuver moved and Mrs. Cain-Criswell seconded that the Twinsburg Board of Education approves the attached Fiscal Tax Budget for the school year commencing July 1, 2014. See pages 11-22 Ayes: Mrs. Cain-Criswell, Mrs. Davis, Mr. Felber, Mr. Stuver, and Mrs. Turle-Waldron. The Board President declared the motion approved. Mrs. Davis moved and Mrs. Turle-Waldron seconded that the Twinsburg Board of Education adopt resolutions 14-036 to 14-039. 14-036 Minutes That the Twinsburg Board of Education approves the Minutes for the regular meeting Regular meeting of December 18, 2013 Special meeting of December 12, 2013 14-037 Financial Report That the Twinsburg Board of Education accepts the following Financial Report for the month of November 2013: Bank Reconciliation, General Fund Financial Summary Report and Financial Report by Fund. See pages 23-28 14-038 Check Register That the Twinsburg Board of Education accepts the Check Registers for the Month of November 2013, the total including payroll and debt payment is $7,542,816.95, as set forth under separate cover. -

By John B. Abbott. It Seems Fitting That the Tolkien Society Should Compile

J .R .R.TOLKIEN : A BIBLOIGRAPHY . by John B. A b b o tt. I t seems fitting that the Tolkien Society should compile a comprehensive bibliography for reference purposes. The following list is intended as a starting-point and is obviously Incomplete. Perhaps other readers will provide additional data and correct any errors''I have made. Books and contributions to journals. 1. "A Middle-English Vocabulary".1922 2. "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight". Edited with E .V . Gordon 1925. 5. "Chaucer as a P h ilologist". P hilological Society. 1934. 4. "Beowulf. The Monsters and the Critics". ("Proc. Brit. Acad." xxii. 22.) 1936. 5. "The Hobbit". George Allen Unwin, Ltd. (London) 1937. 6. "Aotrou and Itroun". (Welsh Review") 1945. 7. "Leaf by Niggle". (Dublin Review) 1947. 8. "On Fairy-Stories". ("Essays Presented to Charles Williams") Oxford University Press. 1047. 9. "The Homdcoming of Beorhtndth Beorhthelm's Son". ("Essays and Studies for 1953") English Association. 1953. A play based on "The Battle of Malden". 10.. "Parmer Giles of Ham". George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. (London) 1949. Illustrated by Pauline Baynes. 11. "The Lord of the Rings" t r ilo g y :- (a ) "The Fellowship of the Ring" 1954. (b ) "The Two Towers" 1955 ( c ) "The Return of the King" 1955. A ll published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. 12. "The Adventures of Tom Bombadil" George Allen & Unwin,Ltd. 1962. Cover and illu stration s by Pauline Baynes. 13. "Tree and Leaf". George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. 1964. Contains both ’7' and '8’ . 14. "Smith of Wootton Major". George Allen &. Unwin, Ltd, 1967. -

Mythlore Index Supplement Issue 101/102 Z 1

MMYYTTHHLLOORREE Index Supplement Issues 101/102 through 103/104 Mythlore Index supplement issue 101/102 Z 1 Article Index by Author • Sorted by author, then alphabetically by title for authors of multiple articles. • Includes abstracts. • Main entries in bold face. A the topic. Concludes that dragons are morally neutral in her world, while Agan, Cami. “Song as Mythic Conduit serpents generally represent or are in The Fellowship of the Ring.” allied with evil. 26.3/4 (#101/102) (2008): 41‐63. This article on song in Middle‐earth Brisbois, Michael J. “The Blade explores the complex layering of history Against the Burden: The and legend that convey Tolkien’s themes Iconography of the Sword in The across a wide array of genres within the Lord of the Rings.” 27.1/2 (#103/104) legendarium, reinforcing the sense of (2008): 93‐103. depth of time Tolkien hoped to achieve Invites us to consider the deeper social even within The Hobbit. implications of carrying and using a sword in the medieval world of Middle‐ earth—how bearing a sword not only B indicates leadership and service, but provides an opportunity for social Basso, Ann McCauley. “Fair Lady mobility, in addition to its more obvious Goldberry, Daughter of the River.” military meanings. Considers as 27.1/2 (#103/104) (2008): 137‐146. examples Merry and Pippin swearing Examines Goldberry as an intermediary oaths to, respectively, Théoden and figure between noble or ethereal female Denethor; Éowyn’s heroic deeds; and characters like Galadriel and Éowyn and especially Aragorn’s use of the everyday women like Rosie Cotton, and Narsil/Andúril as a symbol of shows how her relationship with Tom legitimacy and service to his people. -

WS21 Classics-Cataloguereduced

Abridged Classics Oxymoronica John Atkinson Dr. MardyGrothe Abridged Classics: Brief Summaries of Books You Were Many of the most trenchant observations about the Supposed to Read but Probably Didn’t is packed with human experience engage in oxymoronic word play. Less dozens of humorous super-condensed summations of is more is a famous example; or The more things change, some of the most famous works of literature from many the more they stay the same. Here for the first time is a of the world’s most revered authors, including William collection of hundreds of thought-provoking and Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Emily Brontë, Leo Tolstoy, mind-stretching observations that are false and 9780062747853 Jane Austen, Mark Twain, J.R.R. Tolkien, Margaret 9780060537005 contradictory at a superficial level, and true, logical and Pub Date:6/5/2018 Atwood, James Joyce, Plato, Er... Pub Date:6/9/2015 often profound on a deeper... $24.99 CAD $15.99 CAD 160 pages • Hardcover 272 pages • Paperback How to Read Poetry Like a Professor Complete JaneAusten Thomas C.Foster Anna Milbourne, Simona Bursi No literary form is as admired and feared as poetry. This beautifully illustrated book contains all seven of Jane Admired for its lengthy pedigree—a line of poets Austen’s novels, beautifully retold as stories for children. extending back to a time before recorded history—and a The retellings are true to Austen’s elegant phrasing and ubiquitous presence in virtually all cultures, poetry is also language, while reducing and simplifying the stories for a revered for its great beauty and the powerful emotions it young modern reader, and include quotations from the evokes. -

March 2001 to February 2011

Beyond Bree Back Issues: The Third Decade March 2001 - February 2011 Nancy Martsch, PO Box 55372, Sherman Oaks, CA 91413; [email protected] March 2001: 20th Anniversary. Cover, 1st "Tolkien SIG News". "History of "'Beyond Bree'''. "Tolkien Conference and Bree Moot 5 at the University of St Thomas", "2001: A Tolkien Odyssey, Unquendor's 4th Lustrum". "Tolkien on CS Lewis' Space Trilogy" by Robert Acker, "Tolkien Scrapbook", "Tolkien Music on the Web" by Chris Seeman & Morgueldar Dragonseye, musical "Sagan om Ringen". Review of Mallorn 38. Poem "Shadows on the Shire" by Matthew Anish. "Mithril Miniatures". "Postal Rate Increase". Publications, Letters, News. 12 pp. April 2001: "T olkien . and Swithin . Beneath the North Atlantic Ocean" by Antony Swithin [Dr William Sarjeantl (maps). Reviews: Visualizing Middle·earth (Chris Seeman), "Two January 2001 Lord of the Rings Stage Premieres in Finland" (Mikael Ahlstrom), The Starlit Jewel: Songs from JRR Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit (David Bratman). "Tolkien Conference and Bree Moot 5", "The 'Beyond Bree' Award", "Decipher Takes Another Key license for Lord of the Rings Property", "Postal Rate Increase", "The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter". Publications, News. 12 pp. May 2001: "Tolkien Conf. and Bree Moot 5" (photos), ''The 'Beyond Bree' Award". "Postal Rate Increase", "Rockall", ''lOTR Film News", "Tolkienalia Old & New". Publications, Letters, News. "CS Lewis Home to Host 1st Summer Seminar: Branches to Heaven". "Tolkien Scrapbook","Tolkien Events Past".12pp. June 2001: II10s "Tuna", "Turin Turambar" by Ryszard Derdzinski. "A Talk by Tom Shippey" by Todd Jensen. Poems ''The White Tower" by j culver mead, "At the Borders of Faerie" by Matthew Anish, "'Davo Sin' {'let It Be')", Sindarin trans by David Salo. -

“Above All Shadows Rides the Sun”: Resurrection and Redemption in J.R.R Tolkien's the Lord of the Rings and C.S. Lewis's

“ABOVE ALL SHADOWS RIDES THE SUN”: RESURRECTION AND REDEMPTION IN J.R.R TOLKIEN’S THE LORD OF THE RINGS AND C.S. LEWIS’S THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA by Jaye Dozier, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts with a Major in Literature May 2016 Committee Members: Robert Tally, Chair Steven Beebe Nancy Grayson COPYRIGHT by Jaye Dozier 2016 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Jaye Dozier, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I dedicate this to my family, friends, and all who have supported this endeavor and believed in the importance of fantasy as a revelation of deeper truths. To my committee members, Dr. Grayson and Dr. Beebe, who have stretched my mind and passion for literary studies from the Inklings to the Romantics, and to my chair Dr. Tally, who allowed a scatterbrained graduate student to explore the intersecting realms of fantasy and spirituality with enthusiasm and guidance. I am honored and blessed to know you all. The peculiar quality of the ”joy” in successful Fantasy can thus be explained as a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth. -

Fan Cartography's Engagement with Tolkien's Legendarium Stentor Danielson Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 4 2018 Re-reading the Map of Middle-earth: Fan Cartography's Engagement with Tolkien's Legendarium Stentor Danielson Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Danielson, Stentor (2018) "Re-reading the Map of Middle-earth: Fan Cartography's Engagement with Tolkien's Legendarium," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol6/iss1/4 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Danielson: Re-reading the Map of Middle-earth Introduction In Chapter 1 of The Hobbit, we learn of our protagonist Bilbo Baggins that “He loved maps, and in his hall there hung a large one of the Country Round with all his favourite walks marked on it in red ink” (Tolkien 1966, p. 32-33). Some decades later, Bilbo's distant cousin Pippin laments his failure to have fully consulted the maps available in Rivendell before the Fellowship departed on its long journey (Tolkien 1965a, p. 370). From a handful of references such as these, we know that cartography existed in Middle-earth, and indeed that it was considered a perfectly ordinary and sensible thing to look at a map to find one's way. -

The Chronicles of War Repercussions in J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis's

The Chronicles of War Repercussions in J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis’s Life and Work by Nora Alfaiz B.A. in English, May 2007, King Saud University M.A. in English, May 2011, American University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2020 Dissertation directed by Marshall Alcorn Professor of English The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Nora Alfaiz has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of May 06, 2020. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. The Chronicles of War Repercussions in J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis’s Life and Work Nora Alfaiz Dissertation Research Committee: Marshall Alcorn, Professor of English, Dissertation Director Kavita Daiya, Associate Professor of English, Committee Member Maria Frawley, Professor of English, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2020 by Nora Alfaiz All rights reserved iii Dedication To the writer of The Hobbit. And to my mother, who nudged me towards bookshops and calls me her Precious. iv Acknowledgments I could not have made it this far without my Dissertation Director, Marshall Alcorn, whose class lectures spurred my interest in trauma studies and eventually led to years of office visits and samosa meetings as I looked more into the Great War’s influence on my writers. I am also grateful to Kavita Daiya and Maria Frawley for their invaluable support from the first classroom discussion till the end of my doctoral experience. -

JRR Tolkien's Other Works for Children

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 6 | Issue 2 Article 9 2018 Beyond The obbitH : J.R.R. Tolkien’s Other Works for Children Janet Brennan Croft Rutgers University - New Brunswick/Piscataway, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Croft, Janet Brennan (2018) "Beyond The oH bbit: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Other Works for Children," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol6/iss2/9 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Croft: Beyond The Hobbit Beyond The Hobbit: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Other Works for Children Janet Brennan Croft, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey — As presented at The New York Tolkien Conference, March 17, 2019 — This presentation expands and updates an article I wrote in 2003 for World Literature Today SLIDE 1: Title: The birthday cake from Smith of Wootton Major SLIDE 2: Tolkien with his four children in the garden, Oxford, 26 July 1936 John Ronald Reuel Tolkien is best known to the world as the author of the classic fantasies The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. In his professional life, he was a superb philologist, a skilled translator, the author of a seminal essay on Beowulf, and a contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary. -

Edited Version (970.0Kb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2018 The Other Middle-earth: Intertextuality and Iconography in Sergei Iukhimov's Illustrations for The Lord of the Rings Merriner, Joel http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/13069 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. The Other Middle-earth: Intertextuality and Iconography in Sergei Iukhimov’s Illustrations for The Lord of the Rings by Joel Merriner A thesis submitted to University of Plymouth In partial fulfilment for the degree of Research Masters in Art History School of Humanities and Performing Arts January 2018 2 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION At no time during the registration for the degree of Research Masters (ResM) has the author been registered for any other University award without prior agreement of the Doctoral College Quality Sub-Committee. Work submitted for this research degree at the University of Plymouth has not formed part of any other degree either at the University of Plymouth or at another establishment. -

Download Download

Issue 53 • Spring 2012 MallornThe Journal of the Tolkien Society Mallorn The Journal of the Tolkien Society Issue 53 • Spring 2012 Editor: Henry Gee Production & editorial 4 Kristine Larsen takes a look at Tolkien through her telescope design: Colin Sullivan Cover art: At the Cracks of letters 9 Troels Forchhammer unravels the mysteries of the 1961 Nobel prize Doom by Ted Nasmith Inside: Lorenzo Daniele: The Voice of Saruman (p. 2); reviews 11 Janet Brennan Croft on Tolkien and the Study of his Sources Jef Murray: Amon Sul (p. 6), Haven (p. 10), Gandalf 12 Daniel Howick on A Tolkien Tapestry (p. 16), Rhosgobel Doorway 14 Becky Hitchen on Tolkien and the Peril of War (p. 25), Cair Paravel (p. 28), 15 Troels Forchhammer on Tolkien Studies, Volume VIII Frodo and Strider (p. 31), 17 Pat Reynolds on Among Others Warg Rider (p. 33), Gandalf 18 Harley J Sims on The Lord of the Rings: War in the North (p. 35), Galadriel (p. 40), 20 Sharron Sarthou on C. S. Lewis’s Lost Aeneid Alatar (p. 42), Radagast (p. 45), Mage of Rhosgobel commentary (p. 48); Cor Blok: Rivendell 22 Colin Duriez What made J. R. R. Tolkien tick and why was he called ‘Reuel’? The (p. 13), Lothlórien I (p. 13), importance of Tolkien biography The Petrified Trolls (p. 21); Ted Nasmith: Barrel Rider 26 Kristine Larsen From Dunne to Desmond: disembodied time travel in Tolkien, (p. 23), The Shire: A View Stapledon and Lost of Hobbiton From The Hill 30 Virginia Luling Going back: time travel in Tolkien and E. -

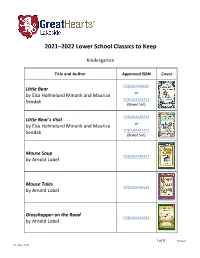

2021–2022 Lower School Classics to Keep

2021–2022 Lower School Classics to Keep Kindergarten Title and Author Approved ISBN Cover 9780064440042 Little Bear by Elsa Holmelund Minarik and Maurice or Sendak 9780064441971 (Boxed Set) 9780064440233 Little Bear’s Visit by Elsa Holmelund Minarik and Maurice or Sendak 9780064441971 (Boxed Set) Mouse Soup 9780064440417 by Arnold Lobel Mouse Tales 9780064440134 by Arnold Lobel Grasshopper on the Road 9780064440943 by Arnold Lobel 1 of 8 Version 1.0 - May 2020 First Grade Title and Author Approved ISBN Cover Owl at Home 9780064440349 by Arnold Lobel The Frog and Toad Collection (Boxed Set) 9780060580865 by Arnold Lobel Sam the Minuteman 9780064441070 by Nathaniel Benchley and Arnold Lobel A Bargain for Frances 9780064440011 by Russell Hoban and Lillian Hoban Three Tales of My Father’s Dragon 9780679889113 by Ruth Stiles Gannett 2 of 8 Version 2.0 - May 2021 Second Grade Title and Author Approved ISBN Cover The Courage of Sarah Noble 9780689715402 by Alice Dalgliesh and Leonard Weisgard Sarah, Plain and Tall 9780062399526 by Patricia MacLachlan The Boxcar Children (No. 1) by Gertrude Chandler Warner and L. Kate 9780807508527 Deal 9780064400015 (Paperback) Little House in the Big Woods or by Laura Ingalls Wilder and Garth Williams 9780060581800 (Full Color Edition) 9780064400558 (Paperback) Charlotte’s Web or by E.B. White and Garth Williams 9780064410939 (Full Color Edition) 3 of 8 Version 2.0 - May 2021 Third Grade Title and Author Approved ISBN Cover 9780064400022 (Paperback) Little House on the Prairie or by Laura Ingalls Wilder and Garth Williams 9780060581817 (Full Color Edition) 9780064408677 (Paperback) The Trumpet of the Swan or by E.B.