UC Berkeley California Journal of Politics and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

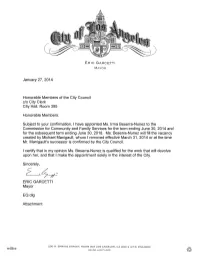

Subject to Your Confirmation, I Have Appointed Ms

ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR January 27, 2014 Honorable Members of the City Council c/o City Clerk City Hall, Room 395 Honorable Members: Subject to your confirmation, I have appointed Ms. Irma Beserra-Nunez to the Commission for Community and Family Services for the term ending June 30, 2014 and for the subsequent term ending June 30, 2018. Ms. Beserra-Nunez will fill the vacancy created by Michael Manigault, whom I removed effective March 31,2014 or at the time Mr. Manigault's successor is confirmed by the City Council. I certify that in my opinion Ms. Beserra-Nunez is qualified for the work that will devolve upon her, and that I make the appointment solely in the interest of the City. Sincerely, L471~ ERIC GARCETTI Mayor EG:dlg Attachment 200 N. SPR!NG STREET, ROOM 303 LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 (213) 978-0600 MAYOR.LACITY.ORG COMMISSION APPOINTMENT FORM Name: Irma Beserra-Nunez Commission: Commission for Community and Family Services End of Term: 6/30/2014 Appointee Information 1. Race/ethnicity: Latina 2. Gender: Female 3. Council district and neighborhood of residence: 5 - SouthValley 4. Are you a registered voter? Yes 5. Prior commission experience: 6. Highest level of education completed: BA California State University Los Angeles 7. Occupation/profession: Advocate for Adult Education 8. Experience(s) that qualifies person for appointment: See attached resume 9. Purpose of this appointment: Replacement 10. Current composition of the commission (excluding appointee): ·,{Narnc{ 1< APCr .. liCD > Gender •.A.r>btdate Te"';~nd~ AI-Mansour, Chancela East LA 14 African American F 25-Seo-12 30-Jun-16 Castillo, Carolina East LA 14 Latina F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Chan, Yvonne North Valley 12 Asian Pacific Islander F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-14 Duardo, Debra East LA 14 Latina F 22-Jun-11 30-Jun-14 Garcia, Marv South Valley 2 Latina F 08-0ct-10 30-Jun-16 Hill, PeQQY Central 4 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 lqlehart, Alfreda Central 10 African American F 30-Jul-10 30-Jun-16 Lara, Alicia Central 4 Latina F 28-Seo-10 30-Jun-14 Little, Marc T. -

MARCH 2010 VOICE .Indd

THE VOICE Circulation - 20,000 323.221.7400 www.thevoicepub.com MARCH 2010 California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Continue To Operate With Disregard To Public Safety By Carlos Morales and was then ordered to leave The Number One Source AAnothernother EExamplexample ooff PParoleesarolees BBeingeing PPlacedlaced IInn For News in Serving On February 13, 2010 at the Humble House facility by its Northeast Los Angeles approximately 10:30pm. West TThehe MMiddleiddle ooff OOurur NNeighborhoodseighborhoods house managers for his failure Covina police offi cers responded to follow the rules and guide- to a shots fi red call, 1800 block lines some three weeks prior to of West Badillo Street. February 14, 2010. Police shortly found out that We also obtained information IINN TTHISHIS four people were inside the home that the managers of the Humble being held hostage. They called House had notifi ed his assigned IISSUESSUE in SWAT to handle the situation. parole agent R. Duran that Swat Team offi cers subsequently Aguilera was no longer resid- responded to the location, Some- ing at their Sober Living Home time shortly after midnight a Swat Facility. Team sniper observed a male in- On Jan 25, 2010 the new Non- NNEWEW dividual through an upstairs win- Revocable Parole Policy took dow holding a fi rearm to a victims SSierraierra PParkark EElementarylementary iiss ttwowo bblockslocks aawayway effect. Was Aguilera case simply MMOVEOVE head. transferred over to this new One shot was fi red by one of the record was at the Humble House Sex, Alcohol and Other) and the policy? This new parole policy West Covina Swat Team mem- a Sober Living Home located at same can be stated with refer- states that parolees re-assigned OOVERVER LLAWAW bers. -

Irma Beserra Núñez: Resumé and Biography - June 10, 2021

Irma Beserra Núñez: Resumé and Biography - June 10, 2021 ARCHIVIST, HISTORICAL PRESERVATIONIST, EDUCATOR & ADVOCATE (2005-present) Doña Irma MAHA: MEXICAN AMERICAN HERITAGE ARTS INSTITUTE Founder/Owner: Archivist, Heritage Arts Educator, and Community RevitalizaLon Advocate (2014-present) RICET Don Juan REVITALIZATION INNOVATIONS Community Cultural EducaLonal Tourism iniLaLve Partner: Director of AdministraLon and Community RelaLons, Assistant Muralist/Designer, and Graphic ArLst (2012-present) COALITION TO SAVE THE FIRST STREET STORE: CHICANO HISTORICAL MONUMENT Co-Founder/Co-Chair: Lead Advocate and ArLst Spokesperson (1970 project concept and theme, architectural/plaza/fountain design and sculpture by internaConally renown arCst “Don Juan” Johnny D. González (1974) nineteen panel mural series designed by “Don Juan” Johnny D. González, David Botello and Robert Arenivar As CO-LEAD ADVOCATE working with Don Juan, Irma formed a countywide Coali?on to preserve this 47 year old, 175 foot long, interna?onally renowned East L.A. Chicano Historical Monument. AJer gathering over 3,000 signatures on pe??ons and rallying 100s to aLend hearings, Don Juan and Irma received major support working closely with the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Conservancy, Los Angeles County Departments of Regional Planning and Public Works, Office of Supervisor Emeritus Gloria Molina, and con?nuing with the Office of Supervisor Hilda Solis. ParLal List of AddiLonal Supporters: Councilmember Gil Cedillo; Eddie Torres (East L.A. Chamber of Commerce); Ben -

Life and Times" Video Recordings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qr4zn7 No online items KCET-TV Collection of "Life and Times" video recordings Taz Morgan William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/collections/archivesandspecialcollections/ ©2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. KCET-TV Collection of "Life and CSLA-37 1 Times" video recordings KCET-TV Collection of "Life and Times" video recordings Collection number: CSLA-37 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Taz Morgan Date Completed: October 2013 Encoded by: Taz Morgan 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: KCET-TV Collection of "Life and Times" video recordings Dates: 1991-2007 Collection number: CSLA-37 Creator: KCET (Television station : Los Angeles, Calif.) Collection Size: 3,472 videotapes (332 boxes) Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Duplication of program tapes for research use is required in accordance with departmental policy regarding the formats of the videotapes of this collection: "Certain media formats may need specialized third party vendor services. If the department does not own a researcher access copy (DVD copy), the cost of reproduction, to be paid fully by patron, will include 1) any necessary preservation efforts upon the original, 2) a master file to be retained by Archives and Special Collections, 3) a researcher viewing copy to be retained by Archives and Special Collections, and 4) the patron copy. -

Bill Rosendahl-Adelphia Communications Corporation Collection of Public Affairs Television Programs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2870379s No online items Bill Rosendahl-Adelphia Communications Corporation Collection of Public Affairs Television Programs Taz Morgan William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/collections/archivesandspecialcollections/ © 2011 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. AV001 1 Bill Rosendahl-Adelphia Communications Corporation Collection of Public Affairs Television Programs Collection number: AV001 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Taz Morgan Date Completed: November 2011 Encoded by: Taz Morgan © 2011 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Bill Rosendahl-Adelphia Communications Corporation Collection of Public Affairs Television Programs Dates: 1987-2006 Collection number: AV001 Creator: Rosendahl, William Joseph "Bill" (1945-) Creator: Adelphia Communications Corporation Creator: Century Communications Corporation Collection Size: 380 linear feet Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: The Bill Rosendahl-Adelphia Communications Corporation Collection of Public Affairs Television Programs consists of videotapes and DVDs, which document the public affairs television programming of Century Communications Corporation and Adelphia Communications Corporation in the Los Angeles metropolitan area between 1987 and 2006. Languages: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Duplication of program tapes for research use is required in accordance with departmental policy regarding the formats of the videotapes of this collection: "Certain media formats may need specialized third party vendor services. -

City of Los Angeles

City of Los Angeles June, 2003 Photo courtesy of Raymond Kwan POLICY FOR THE USE OF CITY TELEPHONE SERVICES BY CITY PERSONNEL * 1. City employees placing long distance and toll calls within the Continental U.S. on City telephone equipment are required to use their individually assigned TELCODE authorization number. All other exceptions, please dial "O" for the City Hall Operator’s assistance. 2. "Reverse charges" or "collect calls" shall only be accepted when such calls are necessary for the proper and efficient performance of City business. City business shall be defined as it appears in Section 4.242(f) of the Los Angeles Administrative Code. 3. "Third Number" charging of calls to City telephone numbers is prohibited. All credit card billing is acceptable. 4. The Information Technology Agency is authorized to issue telephone credit cards to City personnel when such personnel are frequently required to use non-City telephones in conducting City business. Such credit card shall only be issued when requested in writing by City department, office or bureau head. 5. Telegrams and Mailgrams are not to be charged to a City telephone number or a City telephone credit card. Telegrams may be placed through the City Hall Operator. 6. Public pay telephones are located in or near most City offices for the convenience of City personnel. Personal calls shall not be made from City telephones except for emergencies. Supervisors shall advise their subordinates of this policy and take reasonable steps to enforce same. 7. The Information Technology Agency shall be reimbursed for personal calls made from City telephone facilities as follows: A. -

1999 Fall Public Record

Public Record Law School Publications Fall 9-1-1999 1999 Fall Public Record Loyola Law School - Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/public_record Repository Citation Loyola Law School - Los Angeles, "1999 Fall Public Record" (1999). Public Record. 24. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/public_record/24 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Record by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UBLIC ORD The Alumni NewsleHer of Loyola Law School, Los Angeles Fall 1999 Orange County Graduates Will Honor Mark Robinson at Annual O.C. Alumni Dinner Last year, the annual Orange County Alumni Dinner sold out with more than 200 alums attending the event honoring Professor Emeritus William G. Coskran '59. This November, the achievements of Alumnus Mark P. Robinson, Jr. '70 will be recognized at the November 4 Dinner. Asenior partner at Robinson , Calcagnie & Robinson of Laguna Niguel, and the new president of the Consumer Attorneys of California, Robinson was one of the plaintiffs' attorneys in the recent $4.9 billion verdict against General Motors- the largest award ever given in a personal injmy lawsuit. A specialist in product liability cases, Robinson has been counsel or co-counsel in cases in more than 20 states, inclu<ling the landmark Ford Pinto case of Gl'imshaw v. Ford Motor Company with his mentor and partner Art Hews, in which the jury awarded $129 million in compensatmy and punitive damages. -

Angels Walk Union Station

SPECIAL THANKS TO ANGELS WALK LA ADVISORY BOARD Angels Walk LA is a California not-for-profit public benefit corporation supported by: ANGELS WALK Mayor Richard J. Riordan CATELLUS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION UNION STATION HONORARY CHAIRMAN The City Council of the City of Los Angeles Nick Patsaouras, Patsaouras & Associates Council Member Rita Walters THE COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES Council Member Nick Pacheco MEMBERS Daniel Adler, Creative Artists Agency Council Member Mike Hernandez Michael Antonovich, County Supervisor, 5th District THE LOS ANGELES CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU Kenneth Aran, Attorney, Aran, Polk & Berke Law Firm Rockwell Schnabel, Chair FRIENDS OF ANGELS WALK Robert Barrett, Los Angeles Convention & Visitors Bureau George D. Kirkland, President James de la Loza, Executive Officer, Countywide Planning and Development, THE LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Richard Alatorre Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Marjorie Aran George Eslinger, Project Director, The L.A. Red Car Project THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY / Tom Gilmore, President, Gilmore Associates METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY Frances Banerjee EL PUEBLO Lynne Jewell, Director of Public Affairs, Los Angeles Times Los Angeles Department of Transportation Board of Directors – 2000 Jack Kyser, Director of Economic Information and Analysis Leah Bishop Economic Development Corporation Supervisor Michael Antonovich O’Melveny & Myers LLP Tom La Bonge, Director of Community Relations, Supervisor Yvonne Burke, Chair Robin Blair Department of Water and Power Supervisor Don Knabe Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Adolfo V. Nodal, Director, Culture Affairs Supervisor Gloria Molina Rogerio Carvalheiro Anne Peaks, Vice President, The Yellin Company Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky Daniel Rosenfeld, Principal, Urban Partners, LLC Mayor Richard Riordan The J. -

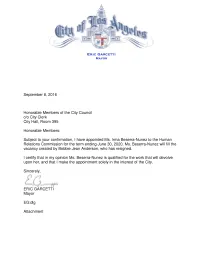

Subject to Your Confirmation, I Have Appointed Ms

A Eric Garcetti Mayor September 8, 2016 Honorable Members of the City Council c/o City Clerk City Hall, Room 395 Honorable Members: Subject to your confirmation, I have appointed Ms. Irma Beserra-Nunez to the Human Relations Commission for the term ending June 30, 2020. Ms. Beserra-Nunez will fill the vacancy created by Bobbie Jean Anderson, who has resigned. I certify that in my opinion Ms. Beserra-Nunez is qualified for the work that will devolve upon her, and that I make the appointment solely in the interest of the City. Sincerely, ERIC GARCETTI Mayor EG:dlg Attachment COMMISSION APPOINTMENT FORM Name: Irma Beserra-Nunez Commission: Human Relations Commission End of Term: 6/30/2020 Appointee Information 1. Race/ethnicity: Latina 2. Gender: Female 3. Council district and neighborhood of residence: 5 - South Valley 4. Are you a registered voter? Yes 5. Prior commission experience: Commission for Community and Family Services 6. Highest level of education completed: B.A., California State University Los Angeles 7. Occupation/profession: Advocate for Adult Education 8. Experience(s) that qualifies person for appointment: See attached resume 9. Purpose of this appointment: Replacement 10. Current composition of the commission (excluding appointee): Commissioner APC CD Ethnicity Gender Term End Boorstin, Leni I. South Valley 2 Caucasian F 30-Jun-18 Campos, Daniel North Valley 7 Latino M 30-Jun-18 Dela Cruz-Viesca, Melany South Valley 4 Asian Pacific Islander F 30-Jun-20 Herr, James East LA 13 Asian Pacific Islander M 30-Jun-20 Khalsa, Nirinjan -

Appendix C: Public Participation

Appendix C: Public Participation IV-C Arroyo Seco Watershed Restoration Feasibility Study Stakeholder Committee (Participants Invited as of 11/3/00) Non-Profit Organizations Los Angeles Conservation Corps Above the Bowl Neighborhood Association Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition Alta San Rafael Association Montana Central Banner Altadena Family Apartment Muir Heights Association Altadena Foothills Conservancy Neighborhood Housing Services Altos Arroyo Association Neighborhood Strengthening Project American Youth Soccer Organization New Horizon School Arroyo Arts Collective Orange Grove Village No. 1 HOA Arroyo Seco Community Action Outward Bound Adventure Arroyo Seco Magnet School Pasadena Beautiful Foundation Arroyo Seco Residents Pasadena Garden Club ARTScorpLA Pasadena Heritage National Audubon Society, Audubon Center Pasadena Historical Museum Audubon Society, Pasadena Pasadena Tournament of Roses California Cycleways People for Pasadena Parks California Native Plant Society Putney Area Neighbors Castle Green Association San Gabriel Mountains Regional Conservancy Cleveland Neighborhood San Pasqual Stables Continental Townhomes Homeowners Assoc. San Rafael Association Cypress-Lincoln-Villa Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy Advisory Del Mar Townhouses Committee East Arroyo Neighbors Save Open Space in the Arroyo Seco Parklands East Arroyo Residents Save South Pasadena Arroyo Seco Parklands East Arroyo Terrace Seco Neighborhood Association East California Neighborhood Association Sierra Club Equestrian Trails, Inc. Singer Park Neighborhood -

THE ROOTS of LATINO URBAN AGENCY

THE ROOTS of LATINO URBAN AGENCY THE ROOTS of LATINO URBAN AGENCY Edited by Sharon A. Navarro and Rodolfo Rosales Number 8 in the Al Filo: Mexican American Studies Series Roberto R. Calderón, Series Editor Denton, Texas Collection ©2013 University of North Texas Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Permissions: University of North Texas Press 1155 Union Circle #311336 Denton, TX 76203-5017 The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, z39. 48. 1984. Binding materials have been chosen for durability. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The roots of Latino urban agency / edited by Sharon A. Navarro and Rodolfo Rosales. — 1st ed. p. cm. — (Number 8 in Al filo: Mexican American studies series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57441-530-8 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57441-542-1 (e-book) 1. Hispanic Americans—Politics and government. 2. Political participation— United States. 3. Metropolitan government—United States. 4. United States— Ethnic relations—Political aspects. I. Navarro, Sharon Ann. II. Rosales, Rodolfo. III. Series: Al Filo ; no. 8. E184. S75R685 2013 320. 50868’073—dc23 The Roots of Latino Urban Agency is Number 8 in the Al Filo: Mexican American Studies Series. The electronic edition of this book was made possible by the support of the Vick Family Foundation. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: Latino Urban Agency Sharon A. Navarro and Rodolfo Rosales 3 1. Latino Political Agency in Los Angeles Past & Present: Diverse Conflicts, Diverse Coalitions, and Fates that Intertwine Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval 13 2.