What If Your Instrument Is Invisible? Dafna Naphtali Publishing As: Naphtali, Dafna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Integrating Technology Jnto the K-12 Music Curriculum. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia

DOCUMENT RESUME SO 022 027 ED 343 837 the K-12 Music TITLE Integrating Technology Jnto Curriculum. State Superintendent of INSTITUTION Washington Office of the Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Jun 90 NOTE 247p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use(055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. *Computer Software; DESCRIPTORS Computer Assisted Instruction; Computer Uses in Education;Curriculum Development; Educational Resources;*Educational Technology; Elementary Secondary Education;*Music Education; *State Curriculum Guides;Student Educational Objectives Interface; *Washington IDENTIFIERS *Musical Instrument Digital ABSTRACT This guide is intended toprovide resources for The focus of integrating technologyinto the K-12 music curriculum. (Musical the guide is on computersoftware and the use of MIDI The guide gives Instrument DigitalInterface) in the music classroom. that integrate two examples ofcommercially available curricula on the technology as well as lessonplans that incorporate technology and music subjects of music fundamentals,aural literacy composition, concerning history. The guide providesERIC listings and literature containing information computer assistedinstruction. Ten appendices including lists of on music-relatedtechnology are provided, MIDI equipment software, softwarepublishers, books and videos, manufacturers, and book andperiodical pu'lishers. (DB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS arethe best that can be made from the original document. *************************,.********************************************* -

California Symphony Returns to Live Performances for 2021/22 Season

CALIFORNIA SYMPHONY RETURNS TO LIVE PERFORMANCES FOR 2021-22 SEASON FIVE CONCERTS SEPTEMBER 18, 2021 – MAY 15, 2022 TWO WORLD PREMIERES FROM CALIFORNIA SYMPHONY YOUNG AMERICAN COMPOSERS-IN-RESIDENCE, DEEPENING COMMITMENT TO COMMUNITY AND DIVERSITY Subscriptions available now. Single tickets go on sale August 13. WALNUT CREEK, CA (5 August 2021) – Following a strong virtual season that attracted new audiences from across the state and around the world, California Symphony, under the leadership of Music Director Donato Cabrera, returns to live concerts at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek for its 2021-22 season. California Symphony’s new season furthers its promise to present innovative programming, exciting guest artists, and music by living composers, women, and composers of color. Subscriptions for three, four, or five concerts start at $99 and are available now, while single tickets ($44-74) go on sale beginning August 13. For more information, the public may visit CaliforniaSymphony.org. Season highlights include: • In the 2021-22 season, California Symphony is excited to finally realize its expansion from eight to ten concerts as originally planned for the 2019-20 season, underscoring the organization’s ability to retain and grow its audience. • 35% of composers in the 2021-22 season are living, female, or composers of color, in continuation of California Symphony’s 2017 Commitment to Diversity outlining its dedication to presenting living and underrepresented composers. • Programming includes composers Jessie Montgomery, Marianna Martines, former Composer-in-Residence (2017-20) and recent Rome Prize winner Katherine Balch, George Walker, and current Composer-in-Residence Viet Cuong, featured alongside Beethoven, Haydn, Debussy, Tchaikovsky, Vaughan Williams, and more. -

Technical Essays for Electronic Music Peter Elsea Fall 2002 Introduction

Technical Essays For Electronic Music Peter Elsea Fall 2002 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 2 The Propagation Of Sound .............................................................................................. 3 Acoustics For Music...................................................................................................... 10 The Numbers (and Initials) of Acoustics ...................................................................... 16 Hearing And Perception................................................................................................. 23 Taking The Waveform Apart ........................................................................................ 29 Some Basic Electronics................................................................................................. 34 Decibels And Dynamic Range ................................................................................... 39 Analog Sound Processors ............................................................................................... 43 The Analog Synthesizer............................................................................................... 50 Sampled Sound Processors............................................................................................. 56 An Overview of Computer Music.................................................................................. 62 The Mathematics Of Electronic Music ........................................................................ -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly . -

Goldmark's Wild Amazons Drama and Exoticism in the Penthesilea Overture

Goldmark’s Wild Amazons Drama and Exoticism in the Penthesilea Overture Jane ROPER Royal College of Music, Prince Consort Road, London E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2016; accepted: March 2017) Abstract: Goldmark was the first of several composers to write a work based on Heinrich von Kleist’s controversial play, Penthesilea. Early critical opinion about the overture was divided. Hanslick found it distasteful, whereas others were thrilled by Goldmark’s powerful treatment of the subject. Composed in 1879, during the 1880s Penthesilea became established in orchestral repertoire throughout Europe and Amer- ica. The overture represents the conflict of violence and sexual attraction between the Queen of the Amazons and Achilles. Exoticism in the play is achieved by contrasting brutal violence, irrational behaviour and extreme sensual passion. This is recreated musically by drawing on topics established in opera. Of particular note is the use of dissonance and unexpected modulations, together with extreme rhythmic and dy- namic contrast. A key feature of the music is the interplay between military rhythms representing violence and conflict, and a legato, rocking theme which suggests desire and sensuality. Keywords: Goldmark, Exoticism, Penthesilea Overture The Penthesilea Overture, op. 31, is arguably Carl Goldmark’s most controversial work. Its content is provocative. Consider first of all the subject matter: Goldmark transports us to the battlefield of Troy in the twelfth century BC. Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons, a terrifying, ferocious warrior tribe of women, gallops onto the scene with her retinue. The Amazons are bloodthirsty and hungry for sex, anticipating the men they will capture to enact their fertility ritual. -

Title List of Rbdigital Magazine Subscriptions (May27, 2020)

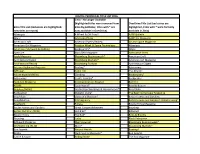

Title List of RBdigital Magazine Subscriptions (May27, 2020) TITLE SUBJECT LANGUAGE PLACE OF PUBLICATION 7 Jours News & General Interest FrencH Canada AD – France Architecture FrencH France AD – Italia Architecture Italian Italy AD – GerMany Architecture GerMan GerMany Advocate Lifestyle EnglisH United States Adweek Business EnglisH United States Affaires Plus (A+) Business FrencH Canada All About History History EnglisH United KingdoM Allure WoMen EnglisH United States American Craft Crafts & Hobbies EnglisH United States American History History EnglisH United States American Poetry Review Literature & Writing EnglisH United States American Theatre Theatre EnglisH United States Aperture Art & Photography EnglisH United States Apple Magazine Computers EnglisH United States Architectural Digest Architecture EnglisH United States Architectural Digest - India Architecture EnglisH India Architectural Digest - MeXico Architecture SpanisH MeXico Art & Décoration - France HoMe & Lifestyle FrencH France Artist’s Magazine Art & Photography EnglisH United States Astronomy Science & TecHnology EnglisH United States Audubon Magazine Science & TecHnology EnglisH United States Australian Knitting Crafts & Hobbies EnglisH Australia Avantages HS HoMe & Lifestyle FrencH France AZURE HoMe & Lifestyle EnglisH Canada Backpacker Sports & Recreation EnglisH United States Bake from ScratcH Food & Beverage EnglisH United States BBC Easycook Food & Beverage EnglisH United KingdoM BBC Good Food Magazine Food & Beverage EnglisH United KingdoM BBC History Magazine -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

02 June 1996 CHART #1012 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Killing Me Softly Give Me One Reason Down On The Upside Collective Soul 1 The Fugees 21 Tracy Chapman 1 Soundgarden 21 Collective Soul Last week - / 1 weeks Platinum / SONY Last week 16 / 16 weeks Gold / WARNER Last week - / 1 weeks Gold / A&M/POLYGRAM Last week 19 / 11 weeks Gold / WARNER Tonight Tonight Pretty Noose To The Faithful Departed Enigma I & Ii 2 Smashing Pumpkins 22 Soundgarden 2 The Cranberries 22 Enigma Last week - / 1 weeks VIRGIN Last week 18 / 2 weeks A&M/POLYGRAM Last week 2 / 4 weeks Platinum / ISLAND/POLYGRAM Last week 16 / 6 weeks Gold / VIRGIN 1,2,3,4 (Sumpin New) Who Can I Run To? Jagged Little Pill Tiny Music . Songs From . 3 Coolio 23 Xscape 3 Alanis Morissette 23 Stone Temple Pilots Last week 2 / 6 weeks Gold / FMR Last week 30 / 4 weeks SONY Last week 3 / 37 weeks Platinum / WARNER Last week 17 / 7 weeks Gold / WARNER California Love Fu-Gee-La Older Zebra Crossing 4 2Pac & Dr Dre 24 The Fugees 4 George Michael 24 Soweto String Quartet Last week 1 / 7 weeks Platinum / ISLAND/POLYGRAM Last week 24 / 11 weeks TRISTAR/SONY Last week 1 / 2 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Last week 23 / 4 weeks Gold / BMG Spaceman Lady Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadne... No Need To Argue 5 Babylon Zoo 25 D'angelo 5 Smashing Pumpkins 25 The Cranberries Last week 14 / 13 weeks Gold / EMI Last week 20 / 7 weeks EMI Last week 14 / 29 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN Last week 32 / 77 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Ridin' Low Don't Stop Sixteen Stone Oyster 6 L.A.D 26 C.D.B. -

The Cure 1983 Album Download Zip the Cure 1983 Album Download Zip

the cure 1983 album download zip The cure 1983 album download zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67ac91da5a088ff7 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Greatest Hits. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £12.49. The Cure were never afraid of artistically defining themselves. They had their own sound, an eerie glamour surrounding a dark whimsicality, yet fans flocked to them throughout the '80s and '90s. Commercial or cult favorites, they're impressive as being one of the '80s' seminal bands who culled more than 30 critical singles. Compilations like 1986's Staring at the Sea: The Singles and 1997's Galore showcased the Cure's accessibility; therefore, having a solid greatest-hits collection might be a bit nonessential. Then again, releasing an album like this at the tip of the new millennium calls for a celebration, and that's what the Cure did. -

Zinio Title List (Exclusives Are Highlighted, New Titles Are Noted) Zinio

DIGITAL PERIODICAL TITLE LIST 2016 Zinio - No Longer Available (highlighted titles were removed from OverDrive Title List (exclusives are Zinio Title List (exclusives are highlighted, Zinio by publisher, titles with * are highlighted, titles with * were formerly new titles are noted) now available in OverDrive) available in Zinio) Allrecipes 4 Wheel & Off Road* AARP Bulletin Allure American Photo AARP the Magazine American Craft American Poetry Review Air and Space Magazine American Girl Magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology Allrecipes American Patchwork & Quilting Backcountry* Allure Aperture Black Belt Magazine Alternative Press AppleMagazine Bloomberg Businessweek* American Craft Architectural Digest Bloomberg Markets* American Girl Magazine Architectural Record Bloomberg Pursuits Architectural Digest Arizona Highways Magazine Boating* Astronomy ARTnews Cabin Life The Atlantic Ask en español (NEW) Climbing Backcountry* Astronomy Cook's Country* Backpacker Audubon Magazine Cosmopolitan en Espanol Barron's AZURE Cycle World* Bead & Button Babybug (NEW) Destination Weddings & Honeymoons* Bead Style Backpacker Diabetic Living* The Beer Connoisseur Magazine Bead Style Electronic Musician* Better Homes and Gardens Bead&Button Fit Pregnancy Better Homes and Gardens' Diabetic Living* Beadwork Fitness Bicycle Times Magazine Better Homes and Gardens Great Garage Makeovers Bicycling Better Nutrition (NEW) Hot Bike* Billboard Bicycle Times Hot Rod* Birds & Blooms Bicycling Lucky Black Enterprise Billboard Magazine Men's Journal Bloomberg Businessweek* -

The Cure — Wikipédia

The Cure — Wikipédia https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cure The Cure 1 The Cure [ðə ˈkjʊə(ɹ)] est un groupe de rock britannique, originaire de Crawley, dans le Sussex The Cure de l'Ouest, en Angleterre. Formé en 1976, le groupe comprend actuellement Robert Smith, Roger O'Donnell aux claviers, Simon Gallup à la basse, Reeves Gabrels à la guitare et Jason Cooper à la batterie. Robert Smith est la figure emblématique du groupe. Il en est le chanteur et le guitariste (il joue également de la basse ou des claviers), le parolier et le principal compositeur. Par ailleurs, il est le seul membre présent depuis l'origine du groupe. The Cure, à Singapour le 1er août 2007. Associé au mouvement new wave, The Cure a Informations générales développé un son qui lui est propre, aux ambiances 2, 3 Pays d'origine Royaume-Uni tour à tour mélancoliques, rock, pop, gothiques Genre musical Cold wave, new wave, et psychédéliques, créant de forts contrastes, où la post-punk, rock alternatif, basse est mise en avant et n’est pas seulement un rock gothique instrument d’accompagnement. Elle est, Années actives Depuis 1976 notamment en raison du jeu particulier de Simon Gallup une composante essentielle de la musique de Labels Fiction Records, Geffen The Cure. L'utilisation conjointe d'une basse six Records cordes (souvent une Fender VI), au son Site officiel www.thecure.com caractéristique, très souvent utilisée dans les motifs (http://www.thecure.com) mélodiques, contribue pour beaucoup à la signature Composition du groupe sonore si singulière du groupe. Membres Robert Smith Cette identité musicale, ainsi qu'une identité Simon Gallup visuelle véhiculée par des clips, contribuent à la Roger O'Donnell popularité du groupe qui atteint son sommet dans Jason Cooper les années 1980. -

3500 ¥25000 ¥2000 ¥4000 ¥10000 ¥4000 ¥3500 ¥3000 ¥5000 ¥5000

ARTHUR RUSSELL ARTHUR RUSSELL BAUHAUS COCTEAU TWINS COCTEAU TWINS World Of Echo First Thought Best Thought In The Flat Field Four-Calendar café Milk & Kisses ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1986年 UPSIDE 【UP600091】 2006年 AUDIKA 【AU10051】 1980年 4AD 【CAD13】 1993年 FONTANA 【5182591】 1996年 FONTANA 【5145011】 US ORIGNAL LP US ORIGNAL 3LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL LP SHRINK STICKER INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥5,000 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥1,500 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥8,000 CONTORTIONS CURE CURE CURE CURE BUY Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me Disintegration Wish Show ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1979年 ZE 【ZE33002】 1987年 FICTION 【FIXH13】 1989年 FICTION 【FIXH14】 1992年 FICTION 【FIXH20】 1993年 FICTION 【FIXH25】 US ORIGNAL LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP INNER SLEEVE / INSERT INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥6,000 価格 ¥3,500 CURE CURE CURE DAVID CUNNINGHAM DAVID SYLVIAN Paris Wild Mood Swings Bloodflowers Grey Scale Blemish ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1993年 FICTION 【FIXH26】 1996年 FICTION 【FIXLP28】 2000年 FICTION 【FIX31】 1977年 PIANO 【PIANO001】 2004年 SAMADHISOUND 【SOUNDLP001】 UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL 2LP UK ORIGINAL LP UK&US ORIGINAL LP INNER SLEEVE INNER SLEEVE INSERT INSERT 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥12,000 価格 ¥6,500 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥2,000 価格 ¥6,000 DAVID SYLVIAN DEAD CAN DANCE DEPECHE MODE DEPECHE MODE DNA Manafon Into The Labyrinth Violator Playing The Angel A Taste Of DNA ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 2010年 SAMADHISOUND 【SOUNDLP002】 1993年 4AD 【DAD3013】 1990年 MUTE -

Contributors

Contributors Roy Ascott is the founding director of the international research network Planetary Collegium (CAiiA-STAR), Professor of Technoetic Arts at the University of Plymouth (England), and Adjunct Professor in Design/Media Arts at the University of California at Los Angeles. He conducts research in art, technology, and consciousness and edits Technoetic Arts. He pioneered the use of cybernetics and telematics in art at the Venice Biennale and Ars Elec- tronica, among others. His most recent publication is Telematic Embrace: Vi- sionary Theories of Art Technology and Consciousness, edited by Edward A. Shanken (University of California Press, 2003). The address of his Web site is <http://www.planetary-collegium.net/people/detail/ra>. Anna Freud Banana began her art career producing batik fabrics and wall hangings but switched to conceptual/performance work with her Town Fool Project in 1971. Through the Banana Rag newsletter, she discovered the In- ternational Mail Art Network (IMAN) which supplies her with banana ma- terial, a sense of community, and affirmation of her conceptual approach. Whether publishing or performing, her intention is to activate her audience and to question authorities and so-called sacred cows in a humorous way. In- ternational Performance/Events and exhibitions on walls, from 1975 to pres- ent, are detailed at <http://users.uniserve.ca/~sn0958>. Tilman Baumgärtel is a Berlin-based independent writer and critic. His re- cent publications include Games. Computerspiele von KünstlerInnen Ausstellungs- katalog (Games. Computergames by artists. Exhibition Catalogue) (2003); Install.exe: Katalog zur ersten Einzelausstellung des Künstlerpaars Jodi bei Plug-In, Basel, Büro Friedrich, Berlin, und Eyebeam, New York (Catalogue for the first solo show of the art duo Jodi at Plug-In, Basel, Büro Friedrich, Berlin, and Eyebeam, New York) (2002); net.art 2.0 Neue Materialien zur Netzkunst / net.art 2.0 (New Materials toward Art on the Internet) (2001); net.art Materi- alien zur Netzkunst (2nd edition, 2001); lettische Ausgabe: Tikla Maksla (2001).