Print 03/03 March 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condition of Designated Sites

Scottish Natural Heritage Condition of Designated Sites Contents Chapter Page Summary ii Condition of Designated Sites (Progress to March 2010) Site Condition Monitoring 1 Purpose of SCM 1 Sites covered by SCM 1 How is SCM implemented? 2 Assessment of condition 2 Activities and management measures in place 3 Summary results of the first cycle of SCM 3 Action taken following a finding of unfavourable status in the assessment 3 Natural features in Unfavourable condition – Scottish Government Targets 4 The 2010 Condition Target Achievement 4 Amphibians and Reptiles 6 Birds 10 Freshwater Fauna 18 Invertebrates 24 Mammals 30 Non-vascular Plants 36 Vascular Plants 42 Marine Habitats 48 Coastal 54 Machair 60 Fen, Marsh and Swamp 66 Lowland Grassland 72 Lowland Heath 78 Lowland Raised Bog 82 Standing Waters 86 Rivers and Streams 92 Woodlands 96 Upland Bogs 102 Upland Fen, Marsh and Swamp 106 Upland Grassland 112 Upland Heathland 118 Upland Inland Rock 124 Montane Habitats 128 Earth Science 134 www.snh.gov.uk i Scottish Natural Heritage Summary Background Scotland has a rich and important diversity of biological and geological features. Many of these species populations, habitats or earth science features are nationally and/ or internationally important and there is a series of nature conservation designations at national (Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)), European (Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA)) and international (Ramsar) levels which seek to protect the best examples. There are a total of 1881 designated sites in Scotland, although their boundaries sometimes overlap, which host a total of 5437 designated natural features. -

Scotland 2014 Outer Hebrides & the Highlands

Scotland 2014 Outer Hebrides & the Highlands 22 May – 7 June 2014 St Kilda Wren, Hirta, St Kilda, Scotland, 30 May 2014 (© Vincent van der Spek) Vincent van der Spek, July 2014 1 highlights Red Grouse (20), Ptarmigan (4-5), Black Grouse (5), American Wigeon (1), Long- tailed Duck (5), three divers in summer plumage: Great Northern (c. 25), Red- throated (dozens) and Black-throated (1), Slavonian Grebe (1), 10.000s of Gannets and 1000s of Fulmars, Red Kite (5), Osprey (2 different nests), White-tailed Eagle (8), Golden Eagle (1), Merlin (2), Corncrake (2), the common Arctic waders in breeding habitat, Dotterel (1), Pectoral Sandpiper (1), sum plum Red-necked Phalarope (2), Great Skua (c. 125), Glaucous Gull (1), Puffin (c. 20.000), Short- eared Owl (1), Rock Dove (many), St Kilda Wren (8), other ssp. from the British Isles (incl. Wren Dunnock and Song Thrush from the Hebrides), Ring Ouzel (4), Scottish Crossbill (9), Snow Bunting (2), Risso’s Dolphin (4), Otter (1). missed species Capercaillie, ‘Irish’ Dipper ssp. hibernicus, the hoped for passage of Long-tailed and Pomarine Skuas, Midgets. Ptarmigan, male, Cairn Gorm, Highlands, Scotland, 3 June 2014 (© Vincent van der Spek) 2 introduction Keete suggested Scotland as a holiday destination several times in the past, so after I dragged her to many tropical destinations instead it was about time we went to the northern part of the British Isles. And I was not to be disappointed! Scotland really is a beautiful place, with great people. Both on the isles, with its wild and sometimes desolate vibe and very friendly folks and in the highlands, there seemed to be a stunning view behind every stunning view. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

The Flight Calls of Crossbills Migrating Over a Southern Pennine Watch Point in Autumn 2019

THE FLIGHT CALLS OF CROSSBILLS MIGRATING OVER A SOUTHERN PENNINE WATCH POINT IN AUTUMN 2019 D.H. Pennington, January 2020 INTRODUCTION In recent years, my birding interest has increasingly been focussed on autumn visible migration in the South Pennines. This has mostly taken place at Harden, on the border of South and West Yorkshire, in the company of Nick Mallinson and, until 2016, Mick Cunningham. In 2014, I began experimenting with sound recording at this site, and this, among several other benefits, soon had the effect of drawing attention to the variations in the flight calls of migrating Common Crossbills. At first, virtually all of these variations were shown by sonograms to belong to one or the other of just two ‘types’. However, this all changed in 2019, when despite it being a very poor autumn in terms of the number of birds passing over (see here for a yearly comparison), at least five different crossbill flight calls were detected. The aims of this article are to document these latest occurrences and, drawing on recently published research, put them into a wider context. CROSSBILL ‘TYPES’? Variability in the vocalisations of Common Crossbills has long been acknowledged, with their flight calls and excitement calls showing the most obvious diversification. However, several studies over the past three decades have shown that individuals are in fact very limited in their call repertoire, and that birds using any particular flight call will invariably use the same associated excitement call. Hence, each individual can be assigned to a vocal ‘type’ (see e.g. Groth 1993, Robb 2000). -

Loxia Scotica

Loxia scotica -- Hartert, 1904 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- FRINGILLIDAE Common names: Scottish Crossbill; European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) At both European and EU27 scales, although this species may have a small range it is not believed to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend is not known, but the population is not believed to be decreasing sufficiently rapidly to approach the thresholds under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern within both Europe and the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: United Kingdom Population The European population is estimated at 4,100-11,400 pairs, which equates to 8,200-22,800 mature individuals. The entire population is found in the EU27. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend In Europe and the EU27 the population size trend is unknown. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Habitats and Ecology This species breeds in lowland forests and stands of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), including open mature plantations and ancient relict forest trees. During the winter it is mostly found in larches (Larix) and in established plantations of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) and sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) as well as well- spaced pine woodland with heather (Calluna) understorey. -

PARROT CROSSBILL Loxia Pytyopsittacus Borkhausen, 1793

HANDBOOK OF WESTERN PALEARCTIC BIRDS FINCHES PARROT CROSSBILL Loxia pytyopsittacus Borkhausen, 1793 Fr. – Bec-croisé des perroquet feeds on seeds of other conifers too, including Ger. – Kiefernkreuzschnabel spruce. Range usually restricted to N Europe and Sp. – Piquituerto lorito; Swe. – Större korsnäbb NW Siberia, but after irruptions may stay and A larger cousin of the Common Crossbill, with a breed elsewhere, e.g. in Scotland. Often associates proportionately heavier bill adapted to opening the with Common Crossbill, making similar irruptions harder cones of Pinus species. However, it also though less numerous. L. c. scotica, o, presumed ad, Scotland, Apr: drop of water on lower mandible makes bill appear L. c. poliogyna, 1stY a, Morocco, Mar: aa average somewhat duller red than curvirostra as can very chunky, but lower mandible still seems rather strong, and culmen is quite sharply curved. be seen from this extreme example photographed in the Atlas Mts. However, it is an imm a, and 1stS a, Finland, Mar: strongly curved mandibles, and depth Although amount of yellowish-green in plumage would indicate ad, as do seemingly greenish edges some older aa attain a somewhat redder plumage than this. Biometrics by and large the same as of lower mandible c. 45% of upper, while tip of lower in profile to most wing-feathers, safe ageing without handling unwise. (F. Desmette) for W & N European populations. (A. B. van den Berg) projects at most marginally. Post-juv moult tends to be rather limited, with 1stY often showing many old feathers. Note moult & Kalko (2009) we prefer to await further research before limit in greater coverts. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

Red Crossbill Percna Subspecies Loxia Curvirostra Percna

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Red Crossbill percna subspecies Loxia curvirostra percna in Canada THREATENED 2016 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Red Crossbill percna subspecies Loxia curvirostra percna in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 62 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Red Crossbill percna subspecies Loxia curvirostra percna in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 46 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Tina D. Leonard for writing the status report on Red Crossbill, percna subspecies (Loxia curvirostra percna) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Marcel Gahbauer, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bec-croisé des sapins de la sous- espèce percna (Loxia curvirostra percna) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Red Crossbill percna subspecies — Image courtesy of D.M. Whitaker. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2016. -

Parrot Crossbills in Britain

Parrot Crossbills in Britain Graham P. Catley and David Hursthouse ollowing an exceptional influx of Parrot Crossbills Loxia pytyopsittacus Finto Britain in the autumn of 1982 (Brit. Birds 76: 46, plates 12, 13 & 220) and subsequent wintering records, we decided to summarise all known past records of this species in Britain and to analyse the 1982/83 influx in the light of previous records and information from other European coun tries. Notes on those observed in 1982/83 also led to points regarding field identification and behaviour. Status of the species The Parrot Crossbill's breeding range is generally quoted (e.g. Vaurie 1959) as extending from Norway, Finland and Sweden east to northern Russia and sporadically south to the Baltic provinces, Poland, the German Democratic Republic and occasionally Denmark. It is nowhere very common, and in the USSR is comparatively common only in the northwest (Dementiev & Gladkov 1954). Breeding densities, like those of the Crossbill L. curvirostra, tend to be higher where there is a good crop of the preferred food source, in the case of Parrot Crossbills cones of pines Pinus. As the pine has a more consistent cone crop than the spruce Picea, the preferred food of the Crossbill, however, Parrot Crossbills can usually adjust to local food shortages by making smaller migratory movements than the highly migratory Crossbill (Nethersole-Thompson 1975). Thus, the Parrot Crossbill may be described as more of a resident or partly erratically eruptive species than the eruptive Crossbill. Migrants regularly reach southern Sweden and Denmark, mostly in late autumn and winter, and occasionally the Federal German Republic, and the species has been recorded exceptionally as far west as Britain and central Europe and also east into Siberia. -

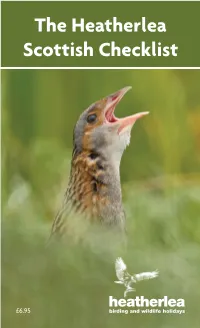

The Heatherlea Scottish Checklist

K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk -%0, birding and wildlife holidays K_`j:_\Zbc`jkY\cfe^jkf @]]fle[#gc\Xj\i\kliekf2 * K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk ?\Xk_\ic\X`jXn`c[c`]\$nXkZ_`e^_fc`[XpZfdgXep# ]fle[\[`e(00(Xe[YXj\[`eJZfkcXe[XkK_\Dflekm`\n ?fk\c#E\k_p9i`[^\%N\_Xm\\eafp\[j_fn`e^k_\Y`i[c`]\ f]JZfkcXe[kfn\ccfm\ik\ek_fljXe[g\fgc\fe^l`[\[ _fc`[Xpj[li`e^k_\cXjk).j\Xjfej#`ecfZXk`fejk_ifl^_flk k_\dX`ecXe[Xe[dfjkf]k_\XZZ\jj`Yc\`jcXe[j#`eZcl[`e^ k_\@ee\iXe[Flk\i?\Yi`[\jXe[XccZfie\ijf]Fibe\pXe[ J_\kcXe[% N\]\\ck_\i\`jXe\\[]fiXÊJZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jkË]filj\ `ek_\Ô\c[#Xe[[\Z`[\[kfgif[lZ\k_`jc`kkc\Yffbc\k]fi pflig\ijfeXclj\%@k`jZfej`jk\ekn`k_Yfk_k_\9i`k`j_ Xe[JZfkk`j_9`i[c`jkjXe[ZfekX`ejXcck_fj\jg\Z`\j`e :Xk\^fi`\j8#9Xe[:% N\_fg\k_`jc`kkc\:_\Zbc`jk`jlj\]lckfpfl#Xe[k_Xkpfl \eafpi\nXi[`e^Xe[i\jgfej`Yc\Y`i[nXkZ_`e^`eJZfkcXe[% K_\?\Xk_\ic\XK\Xd heatherlea birding and wildlife holidays + K_\?\Xk_\ic\XJZfkk`j_ Y`i[`e^p\Xi)'(- N_XkXjlg\iYp\Xif]Y`i[`e^n\\eafp\[Xifle[k_\?`^_cXe[j Xe[@jcXe[j?\i\`jXYi`\]\okiXZk]ifdfli9`i[`e^I\gfik% N\jkXik\[`eAXelXipn`k_cfm\cpC`kkc\8lb`e^ff[eldY\ij # Xe[8d\i`ZXeN`^\fe#>cXlZflj>lccXe[@Z\cXe[>lccfek_\ ZfXjkXd`[k_fljXe[jf]nX[\ijXe[n`c[]fnc%=\YilXipXe[ DXiZ_jXnlj_\X[kfk_\efik_[li`e^Ê?`^_cXe[N`ek\i9`i[`e^Ë# ]\Xkli`e^Jlk_\icXe[Xe[:X`k_e\jj%FliiXi`kpÔe[`e^i\Zfi[_\i\ `j\oZ\cc\ek#Xe[`e)'(-n\jXnI`e^$Y`cc\[Xe[9feXgXik\Ëj>lccj% N`k_>i\\e$n`e^\[K\XcjXe[Jd\nZcfj\ikf_fd\n\n\i\ Xci\X[pYl`c[`e^XY`^p\Xic`jkKfnXi[jk_\\e[f]DXiZ_fliki`gj jkXik\[m`j`k`e^k_\N\jk:fXjk#n`k_jlg\iYFkk\iXe[<X^c\m`\nj% K_`jhlfk\jldj`klge`Z\cp1 Ê<m\ipk_`e^XYflkkf[XpnXjYi\Xk_$kXb`e^N\Ôe`j_\[n`k_