BMH.WS0929.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autobiography Patrick Cudmore

AUTOBIOGRAPHY of PATRICK CUDMORE (1896) □—□ Table of Contents Chapter Pages 1. Preface..................................................................2 2. Autobiography..................................................3-13 3. Excerpts from Herringshaw’s Encyclopedia of American Biography of the Nineteenth Century .....................................13-14 4. The Pedigree of the Cudmore Family..............14-19 5. Related Articles...................................................19 □—□ Preface By Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP Patrick Cudmore had published books on history, satires, poetry, political tracts, polemics and countless newspaper articles and letters to public officials before he finally got around to writing his “Autobiography” in 1896. It has three parts: The first and the longest includes his memoir of his early years in Ireland, where he was born in June 1831, his stops in New York and Wisconsin, before settling in Southeastern Minnesota in 1856. It also includes a description of his service during the Civil War. This section concludes with a catalogue of his numerous writings, and a list of the reasons he “abandoned” the Democratic Party and became a Republican. The second part, a later addition, is the entry on him in Herringshaw’s Encyclopedia of American Biography of the Nineteenth Century , published in 1898. This part concludes with another list of his publications and works-in-progress. The final part, entitled “The Pedigree of the Cudmore Family,” contains the results of his genealogical searches in the early 1900s. The manuscript of Cudmore’s “Autobiography” at the Minnesota Historical Society has this notation at the top of the first page: Originally ten pages, it has been reformatted and several long paragraphs divided. Titles of books and newspapers are italicized unless they are in quotations in the original. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History, 1913-21

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 659 Witness Justin A. McCarthy, 10 Belgrave Square, Monkstown, Dublin. Identity. Quartermaster, Kilfinane Company, Galtee Batt'n. 0/C. 5th (Kilfinane) Battalion, East Limerick Brigade. Subject. National activities, Co. Limerick, 1914-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File NilNo S.1951 FormForm B.S.M.2 STATENT BY MR. JUSTIN McCARTHY, KILFINANE CO. LIMERICK. I was born in the year 1893 at Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. I went to school at St. Munchin's College, Limerick. In the Spring of l9l4 I joined the Irish National Volunteers and became a sub-section leader. At the split between the Irish Volunteers and the original organisation, I joined the former and became leader of the section which became inactive and remained so until reorganised by Ernest Blythe in the Autumn of 1915. The company was about 30 strong and formed part of the Galtee Battalion then under the command of Liam Manahan. We obtained some equipment and a few Smith & Wesson revolvers. We paraded openly with the revolvers and took part with other units at the St. Patrick's Day celebration in Ardpatrick 1916. Some members of the company answered the call on Thursday morning of Easter Week, but I was not one of them. I took part in the East Clare election, June 1917 (for a few days) preparatory to which I attended at Bruree to receive Eamon de Valera on his arrival there from Lewes Gaol from which he left next day for East Clare. -

Obituaries, Death Notices, Etc. - L

Obituaries, death notices, etc. - L Surname Forename Date of Newspaper Address Notes La Nauze Richard 13/05/1871 Omagh for more than 20 years County Surveyor of Limerick Lacey Brian 14/08/1944 St. Ita's Terrace, Newcastlewest, Co. aged 35; died from drowning Limerick Lacey Christopher, Brother 31/07/1948 Glenstal Abbey, Murroe, Co. Limerick native of Naas, first death of Benedictine monk at Glenstal, first burial in Monastery Cemetery Lacey female (Mrs.) 31/10/1785 wife of Mr. Thomas Lacey Lacey female (Mrs.) 06/06/1801 Lock Quay widow of late Thomas Lacey Lacey Francis (Mr.) 01/05/1812 of this City, apothecary Lacey Stephen 16/03/1805 The Canal, Limerick drowned Lacey Thomas 18/06/1800 Newgate Lane grocer Lacey Thomas 20/01/1810 classical tutor, died at house of Mayor, Francis Lloyd Lacey Thomas 18/09/1861 Abbey late of Dromcolloher Lacey Thomas 04/12/1902 'Lacey's Cross', Newcastle West husband of Johanna Lacey; inquest report Lacy Alicia 16/11/1836 Clare Street widow of Edy Lacy, sister of the late John Connell of this city, brewer Lacy Edy 08/12/1824 Clare Street Lacy female (Mrs.) 26/09/1785 North Strand, Limerick wife of Richard Lacy, of Leitrim, Co. Kerry Lacy Francis 10/02/1783 Ballingarry, Co. Limerick Lacy Hugh 04/05/1839 Mary Street builder Lacy J.P. 28/06/1906 Edgbaston report, Limerick native (death notice 30/6/1906) Lacy John 20/04/1789 haberdasher Surname Forename Date of Newspaper Address Notes Lacy male (Mr.) 02/06/1832 Arthur's Quay cholera Lacy Rose 11/03/1854 Mungret Street wife of Stephen Lacy Laffan Alice 15/01/1925 Killonan mother of Bartholomew Laffan, Chairman of Limerick County Council; death notice (obituary, 15/01/1925) Laffan Anne 04/05/1869 Killonan Cottage wife of Bartholomew Laffan Laffan Batt 02/06/1947 Kilonan, Co. -

Derelict Sites Register - September 2019

DERELICT SITES REGISTER - SEPTEMBER 2019 REF NUMBER LOCATION OF LAND DESIGNATED AREA EIRCODE 1 DS-001-91 4 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 2 DS-002-91 3 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 3 DS-003-91 2 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 4 DS-004-91 1 Wellesley Lane, (off Henry Street), Limerick. Limerick City West 5 DS-005-91 23 Wickham Street, Limerick. Limerick City West V94 XN53 6 DS-006-91 22 Wickham Street, Limerick. Limerick City West V94 P2F6 7 DS-001-93 Knightstreet, Ballingarry, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 8 DS-001-97 Tonteere, Caherconlish, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 9 DS-004-04 West end, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 10 DS-005-04 Disused Shop & Shed, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 11 DS-007-04 Main St Croom, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 12 DS-011-04 The Square, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 13 DS-001-05 Market House, Kilfinane, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 14 DS-005-05 Glengort Schoolhouse, Tournafulla Newcastlewest 15 DS-008-06 Main Street, Bruff, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 16 DS-009-06 Ballyvulhane, Bruff, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 17 DS-011-06 Tontere, Caherconlish, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 18 DS-001-07 Corgrigg, Foynes, Co. Limerick. Adare/Rathkeale 19 DS-003-08 Cogan Street, Limerick. Limerick City West 20 DS-005-08 Woodlawn Park, Ballysimon, Limerick. Limerick City East 21 DS-007-08 Ballyneety North, Templebredon, Co. Limerick. Kilmallock/ Cappamore 22 DS-008-08 125 Elm Park, Castletroy, Co. -

BMH.WS1412.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1412. Witness Michael Hennessy, Dundrum, Co. Tipperary. Identity. Member of East Limerick Brigade Flying Column. Subject. Activities of Kilfinane Company, Irish Volunteers, l914-1921, and East Limerick Flying Column, 1920-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.2740. Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY MR. MICHAEL HENNESSY, Dundrum,Co. Tipperary. I joined the Irish Volunteers when a company of that organisation was formed in my native place of Kilfinane, Co. Limerick, towards the end of the year of l914. I was then about twenty-one years of age. There were about thirty young men in the company, and Sean McCarthy, then resident in Kilfinane, was the company 0/C. Justin McCarthy, Sean's cousin, and Dan McCarthy were the other two officers of the company. We paraded about once or twice a week for training and drill. Foot drill was practised in a field near the town, and occasionally we went on route marches to places like Ballylanders and Glenbrohane. The training was done with wooden guns and, as far as I am aware, the company at that time possessed no effective arms. I should also mention that our company the Kilfinane company as it was then known was attached to the Galtee battalion of which, if my memory serves me right, Willie Manahan, then the creamery manager in Ardpatrick, was 0/C. My recollection of Easter Week 1916 is that the company was mobilised to parade on either Easter Sunday or Easter Monday morning, and each man was instructed to bring sufficient rations to maintain him for a couple of days. -

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

Limerick Walking Trails

11. BALLYHOURA WAY 13. Darragh Hills & B F The Ballyhoura Way, which is a 90km way-marked trail, is part of the O’Sullivan Beara Trail. The Way stretches from C John’s Bridge in north Cork to Limerick Junction in County Tipperary, and is essentially a fairly short, easy, low-level Castlegale LOOP route. It’s a varied route which takes you through pastureland of the Golden Vale, along forest trails, driving paths Trailhead: Ballinaboola Woods Situated in the southwest region of Ireland, on the borders of counties Tipperary, Limerick and Cork, Ballyhoura and river bank, across the wooded Ballyhoura Mountains and through the Glen of Aherlow. Country is an area of undulating green pastures, woodlands, hills and mountains. The Darragh Hills, situated to the A Car Park, Ardpatrick, County southeast of Kilfinnane, offer pleasant walking through mixed broadleaf and conifer woodland with some heathland. Directions to trailhead Limerick C The Ballyhoura Way is best accessed at one of seven key trailheads, which provide information map boards and There are wonderful views of the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside with Galtymore in the distance. car parking. These are located reasonably close to other services and facilities, such as shops, accommodation, Services: Ardpatrick (4Km) D Directions to trailhead E restaurants and public transport. The trailheads are located as follows: Dist/Time: Knockduv Loop 5km/ From Kilmallock take the R512, follow past Ballingaddy Church and take the first turn to the left to the R517. Follow Trailhead 1 – John’s Bridge Ballinaboola 10km the R517 south to Kilfinnane. At the Cross Roads in Kilfinnane, turn right and continue on the R517. -

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish

W - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Wade Henry Turagh Tuogh Cappamore Wade John Cahernarry (Cripps) Cahernarry Donaghmore Wade Joseph Drombanny Cahernarry Donaghmore Wakely Ellen Creagh Street, Glin Kilfergus Glin Walker Arthur Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Catherine Blossomhill, Pt. of Rathkeale Rathkeale (Rural) Walker George Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Henry Askeaton Askeaton Askeaton Walker Mary Bishop Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker Thomas Church Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker William Adare Adare Adare Walker William F. Blackabbey Adare Adare Wall Daniel Clashganniff Kilmoylan Shanagolden Wall David Cloon and Commons Stradbally Castleconnell Wall Edmond Ballygubba South Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall Edward Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Edward Ballingarry Ballingarry Ballingarry Wall Ellen Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Ellen Ballynacourty Iveruss Askeaton Wall James Abbeyfeale Town Abbeyfeale Abbeyfeale Wall James Ballycullane St. Peter & Paul's Kilmallock Wall James Bruff Town Bruff Bruff Wall James Mundellihy Dromcolliher Drumcolliher, Broadford Wall Johanna Callohow Cloncrew Drumcollogher Wall John Aughalin Clonelty Knockderry Wall John Ballycormick Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ballygubba North Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall John Clashganniff Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ranahan Rathkeale Rathkeale Wall John Shanagolden Town Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes -

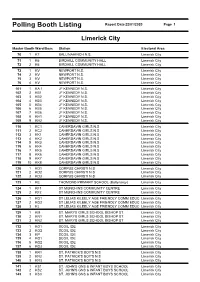

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1 Limerick City Master Booth Ward/Desc Station Electoral Area 70 1 K7 BALLINAHINCH N.S. Limerick City 71 1 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 72 2 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 73 1 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 74 2 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 75 3 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 76 4 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 101 1 KA.1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 102 2 KB1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 103 3 KB2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 104 4 KB3 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 105 5 KB4 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 106 6 KB5 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 107 7 KB6 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 108 8 KH1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 109 9 KH2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 110 1 KC1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 111 2 KC2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 112 3 KK1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 113 4 KK2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 114 5 KK3 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 115 6 KK4 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 116 7 KK5 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 117 8 KK6 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 118 9 KK7 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 119 10 KK8 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 120 1 KD1 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 121 2 KD2 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 122 3 KD3 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 123 1 KE THOMOND PRIMARY SCHOOL (Ballynanty) Limerick City 124 1 KF1 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 125 2 KF2 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 126 1 KG1 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 127 2 KG2 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 128 3 KJ ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 129 1 KM ST. -

Limerick Metropolitan District Movement Framework

Limerick City and County Council Limerick Metropolitan District Movement Framework Study 2 The following people and organisations contributed Mr David Clements to the development of the Movement Framework Organisations/Individuals consulted as part of Study: the development of the study: Limerick City and County Council: Ultan Gogarty – Limerick Institute of Technology Paul Crowe Orlaith Borthwick, Gary Rowan – Limerick Chamber Vincent Murray Miriam Flynn – Bus Éireann Rory McDermott Joe Hoare – University Hospital Limerick Carmel Lynch Insp. Paul Reidy, Sgt. Peter Kelly – An Garda Neal Boyle Síochána John J. Ryan Helen O’Donnell, Philip Danaher – Limerick City Kieran Reeves Business Association Mairead Corrigan Brian Kirby – Mary Immaculate College Robert Reidy, John Moroney – University of Limerick Smarter Travel Office: Limerick Pat O’Neill Michael Curtin – Eurobus Limerick Lise-Ann Sheehan Consultant Members of the Project Team for National Transport Authority: delivery of the Movement Framework Study: Mr Hugh Creegan Tiago Oliveira, Arup Consulting Engineers David O’Keeffe, Arup Consulting Engineers Clifford Killeen, Arup Consulting Engineers Images Photography for this report was provided by Limerick City & County Council and Arup Consulting Engineers. Graphics for this report were provided by Arup Consulting Engineers. 3 Limerick Metropolitan District Movement Framework Study 1 Executive Summary and Introduction 7 1.1 Executive Summary 8 1.2 Introduction - The Limerick Metropolitan District Movement Framework Study 9 2 Literature -

Limerick Senior Men Cross Country Results

Athletics Limerick Senior Men – Cross Country Results 2000 - 2020 Researched and Compiled by Karen Raine, assisted by Rosemary Ryan INDIVIDUAL TEAM 2020 Venue: The Demense Newcastle West Date: Sunday 4th October Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Niall Shanahan An Bru AC (27:28) 1 West Limerick AC 27 2 Declan Moore Bilboa AC (27:33) 2 Limerick AC 41 3 John Kinsella Bilboa AC (27:53) 3 Bilboa AC 53 2019 Venue: Bilboa, Cappamore Date: Sunday 22nd September Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Declan Moore Bilboa AC 1 Limerick AC 42 2 John Kinsella Bilboa AC 2 Dooneen AC 87 3 Martin Doody Limerick AC 3 Bilboa AC 96 2018 Venue: Bilboa, Cappamore Date: Saturday 6th October Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Declan Moore Bilboa A.C. 1 Limerick A.C. 28 2 Niall Riordan An Bru A.C 2 West Limerick A.C. 49 3 Mark Guerin Limerick A.C. 3 Dooneen A.C. 51 2017 Venue: Bilboa, Cappamore Date: 24th September Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Michael Carmody An Brú AC 1 An Brú AC 26 2 Sean Doyle An Brú AC 2 Limerick AC 36 3 Declan Moore Bilboa AC 3 West Limerick AC 47 2016 Venue: Plassey, University of Limerick Date: 2nd October Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Michael Carmody An Bru AC 1 Limerick AC 27 2 Martin Doody Limerick AC 2 Bilboa AC 44 3 Declan Moore Bilboa AC 3 West Limerick AC 47 2015 Venue: Newcastle West Date: 15th November Pos Name Club Pos Club Score 1 Michael Carmody An Brú AC 1 Limerick AC. -

'One Diocese,Many Stories' Limerick Diocesan Assembly

‘ONE DIOCESE, MANY STORIES’ LIMERICK DIOCESAN ASSEMBLY 5th October 2019 Rathkeale House Hotel Table of Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................... 5 Community and Sense of Belonging Theme ................................................... 6 Lectio Divina; Small Christian Communities: Newcastlewest Parish .................................... 7 Welcome and Hospitality: Cratloe Parish .............................................................................. 8 Local Pilgrimage: The Well at Barrigone: St Senan’s Parish (Shanagolden / Foynes / Robertstown) ........................................................................................................................ 10 Trócaire - making the story local: Limerick Diocese Trócaire Volunteer Group .................. 13 Laudato Si; Caring for our Common Home: Salesian Sisters ............................................... 15 Traveller Outreach ............................................................................................................... 16 Missionary Outreach; Synod Group of Frontline Workers .................................................. 17 Pastoral Care of the Family Theme ............................................................... 18 Family Fun Days: World Meeting of Families Diocesan Committee .................................... 19 Visible Reminders of an Invisible