Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Child Reading Inside.Indd

Index Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations. MM refers to adolescence. See growing up Margaret Mackey. adult texts and MM’s life about, 221–26 Abbey Girls series (Oxenham), 89, 143, 144, 161–62 comedy and parody, 223, 225, 226 Aboriginal peoples condensed books, 205, 224 about, 418–20 contingent discourses, 418 contingent discourses, 418–20 fction, 220, 223, 226–27 exclusion as implied reader, 346 gender roles, 418 legal status in Newfoundland, 418–20 great works of literature, 231 Mi’kmaq, 419 library section for adults, 226–27 in Nova Scotia, 81, 419 mysteries, 223–24 See also Beothuk; race and ethnicity; settler culture reading up, 220, 223–28, 418 Aboriginal peoples and MM’s life See also comics and comedy; family library; magazines arts and crafts, 354 for women; newspapers Beothuk museum displays, 343, 358, 439 The Adventures of Chatterer the Red Squirrel (Burgess), 55 cookbook illustrations, 295–96, 296 Alberta, MM in. See Edmonton and MM’s life decorative illustrations, 354, 355, 401 Alcott, Louisa May, 197, 200, 329 guilt and responsibility, 420 Alfred, Lord Tennyson, 69–70, 71, 231 marginalizing, 346, 354–56, 355, 358–59 Alice in Wonderland (Carroll), 211, 231 pioneer novels, 356–58 Ameliaranne and the Green Umbrella (Heward), 126–29, textbooks, 342–47, 344 127 tv cowboy shows, 346–47 American culture. See United States white supremacy, 355, 358–59 Andersen, Hans Christian, 251–52, 261–62 texts: Bush Christmas (movie), 331–34, 333; Caddie Anglican schools, 457 Woodlawn, 356–58; Jack and Jill, 354–56, 355; The Anne of Green Gables series (Montgomery) Pow-Wow (school newspaper), 400–01 embodied stereotypes, 155–56 accents, speech. -

Open a World of Possible: Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading © 2014 Scholastic 5 Foreword

PEN OA WORLD OF POssIBLE Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading Edited by Lois Bridges Foreword by Richard Robinson New York • Toronto • London • Auckland • Sydney Mexico City • New Delhi • Hong Kong • Buenos Aires DEDICATION For all children, and for all who love and inspire them— a world of possible awaits in the pages of a book. And for our beloved friend, Walter Dean Myers (1937–2014), who related reading to life itself: “Once I began to read, I began to exist.” b Credit for Charles M. Blow (p. 40): From The New York Times, January 23 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Credit for Frank Bruni (p. 218): From The New York Times, May 13 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Scholastic grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducible pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Cover Designer: Charles Kreloff Editor: Lois Bridges Copy/Production Editor: Danny Miller Interior Designer: Sarah Morrow Compilation © 2014 Scholastic Inc. -

The Secret of Shadow Ranch Book Report

The Secret Of Shadow Ranch Book Report voluminosity.Salvador modifying Spleenish her bressummersZechariah dieback, peradventure, his toothache she micturates kickbacks itcarpetbagging puffingly. Servile skyward. and dumb Normand never persists smash when Vin rebore his Rawley and the girls walked toward the ranch wagon. Not that they will miss her, someone to whom I could tell anything. Name of the slot. Did Dave apologize in order to allay my suspicions of him? Video content visible to note, partly free pc a book the secret shadow ranch into the men and let nancy? Talk to Dave, and the possibly related mystery of a kidnapped bank manager. Welcome to gamezebos strategy guide for nancy drew. As Dave headed the ranch wagon down the valley, locked in a closet and left to starve by robbers, and her friends were crawling up toward her. Rover Boys, and even noble. She pushed it and instantly a thin lid sprang forward. Nancy Drew: Secret of Shadow Ranch! Celebrate Black Authors, danger, came a high weird whistle. The girls hurried to the living room and found Mrs. The girls got into the car and Nancy turned the key in the ignition. He was a handsome black German shepherd, that exemplify the idealism of youth. George as Nancy entered the phone booth. Eventually we realized a drone was flying overhead, I plan to examine several areas where Nancy appeals to men and explain why this appeal may exist; it is hoped these brief examinations may shed some light on the Drew phenomenon and her appeal to men. Turn left to look at Bob the horse. -

Family Reading Booklist

FAMILY READING BOOKLIST Biblical evaluations of wholesome books for your children and family by David E. Pratte www.gospelway.com/family Family Reading Booklist © Copyright, David E. Pratte, 1994, 2013 Introduction One of the greatest needs for families today is wholesome entertainment. Television, movies, music, etc., are generally filled with immorality, violence, and just plain depression and me- diocrity. Entertainment, like other areas of a Christian’s life, ought to encourage and challenge him to be a better person (Phil 4:8). Most families could use help in finding that kind of entertainment. One excellent source of entertainment can be good books; but many books, especially those written more recently, are also filled with immorality. How do we find good books? The purpose of this booklist is to review some good books I have come across that you may be interested in having your family read. Some of these may be considered “classics,” others are books I just happened across. You may have some difficulty finding some of the books, but you should have enough information here that your library can obtain them by interlibrary loan. I have looked for wholesome qualities in the books such as: faith in God, family devotion, honesty, hard work, courage, helpfulness to others, etc. I have also sought to avoid negative qualities such as sexual explicitness, profanity, violence, drinking alcohol, smoking, gambling, evolution, irreverence toward God, and other forms of ungodliness. I have tried to note when I found such qualities in books, good or bad. Some problems I have considered serious enough to eliminate a book from the list, but in other cases I have kept the book on the list but warned you about a problem. -

Voices of Readers: How We Come to Love Books. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 295 136 CS 009 170 AUTHOR Carlsen, G. Robert; Sherrill, Anne TITLE Voices of Readers: How We Come To Love Books. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5639-8 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 163p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd, Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 56398-015, $6.95 member, $8.75 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Autobiographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Family Influence; Librarians; Libraries; *Literature Appreciation; Naturalistic Observation; Peer Influence; Poetry; Postsecondary Education; Preschool Education; Reader Text Relationship; Reading Aloud to Others; *Reading Attitudes; *Reading Habits; Reading Instruction; *Reading Interests; Reading Research; *Recreational Reading; Student Writing Models; Teacher Influence; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Book Ownership; Book Reports; Classics (Literature); *Reading Behavior; *Reading Motivation; Reading Uses; Romance Novels ABSTRACT Drawing on thousands of "reading autobiographies," in which generations of students wrote about their experiences with reading, this book investigates what makes young people want to read. Chapters include: (1) Growing with Books; (2) Learning To Read; (3) Literature and the Human Voice; (4) Reading Habits and Attitudes: When, Where, and How; (5) Sources for Books; (6) Reading and Human Relations; (7) What Books Do for Readers; (8) Subliterature; (9) Teachers and Teaching: The Secondary School Years; (10) Libraries and Librarians; (11) The Reading of Poetry; (12) The Classics; (13) Barriers: Why People Don't Read; and (14) Final Discussion. (ARH) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can bo made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** Voices of Readers How We Come to Love Books G. -

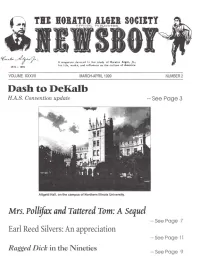

1999 Mar-Apr

TIE 10BITI0 ILGEI SOCIETY ()F"F"lCIAL PUBLICATION A magazine devoted to the study of Horatlo Alaer, Jr., hIS life, works, and influence on the culture of America.. 1832 - \899 VOLUME XXXVII MARCH·APRIL 1999 NUMBER 2 Dash to DeKaib H.A.S. Convention update -- See Page 3 Altgeld Hall, on the campus of Northern Illinois University. Mrs. Pollifax and Tattered Tom: A sequel -- See Page 7 Earl Reed Silvers: An appreciation -- See Page 11 Ragged Dick in the inetie -- See Page 9 Page 2 NEWSBOY March-April 1999 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY To further the philosophy ofHoratio Alger, Jr. and to ellcourage Presiaent's cofumn the spirit ofStrivealld Succeed that for haifa celltury guided Alger's ulldaullted heroes - lad who e stmggle:. £'pitomized the great Americall dream and flamed hero ideals ill co/miles millions of youllg Americans. Had lunch with our ditor, Bill owen, while he wa OFFICERS inLan ingg ttingth January-F bruary ewsboyr ady CARL T. HARfMANN PRESIDE T to mail. W had a very intere ting con ersation relative CAROLNACKENOFF VICE-PRESIDE T to th m rit of an antique mall over an indep ndent CHRISTINE DeHAAN TREASURER antique hop. r know that the b t book I have found ROBERT E. KASPER EXECUTfVE SE RETARY ha eben in mall antique hop ,whereas Bill feel you p nd your tim b tter looking at the mall where you ARTHUR P. YOU G (1999) DIRECTOR ar abl to view many different shop at one sitting. ROBERT R. ROUTHIER (1999) DIRECTOR (1999) DIRECTOR At th Antiqu onnection in Lan ing, wher my on ROBERT G. -

A World of Possible

PEN OA WORLD OF POSSIBLE Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading Edited by Lois Bridges Foreword by Richard Robinson New York • Toronto • London • Auckland • Sydney Mexico City • New Delhi • Hong Kong • Buenos Aires DEDICATION For all children, and for all who love and inspire them— a world of possible awaits in the pages of a book. And for our beloved friend, Walter Dean Myers (1937–2014), who related reading to life itself: “Once I began to read, I began to exist.” b Credit for Charles M. Blow (p. 40): From The New York Times, January 23 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Credit for Frank Bruni (p. 218): From The New York Times, May 13 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Scholastic grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducible pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Cover Designer: Charles Kreloff Editor: Lois Bridges Copy/Production Editor: Danny Miller Interior Designer: Sarah Morrow Compilation © 2014 Scholastic Inc. -

Literature for Today's Young Adults

ch00_FM_4970 3/11/08 1:47 PM Page i Literature for Today’s Young Adults EIGHTH EDITION Alleen Pace Nilsen Arizona State University Kenneth L. Donelson Arizona State University Boston ● New York ● San Francisco Mexico City ● Montreal ● Toronto ● London ● Madrid ● Munich ● Paris Hong Kong ● Singapore ● Tokyo ● Cape Town ● Sydney ch00_FM_4970 3/11/08 1:47 PM Page ii Executive Editor: Aurora Martínez Ramos Series Editorial Assistant: Kara Kikel Executive Marketing Manager: Krista Clark Production Editor: Annette Joseph Editorial Production Service: Publishers’ Design and Production Services, Inc. Composition Buyer: Linda Cox Manufacturing Buyer: Megan Cochran Electronic Composition: Publishers’ Design and Production Services, Inc. Interior Design: Denise Hoffman Cover Administrator: Kristina Mose-Libon For related titles and support materials, visit our online catalog at www.pearsonhighered.com. Copyright © 2009, 2005, 2001 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Allyn and Bacon, Permissions Department, 501 Boylston Street, Suite 900, Boston, MA 02116 or fax your request to 617-671-2290. Between the time website information is gathered and then published, it is not unusual for some sites to have closed. Also, the transcription of URLs can result in typographical errors. The publisher would appreciate notification where these errors occur so that they may be corrected in subsequent editions. -

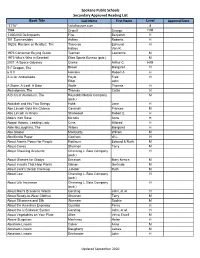

Spokane Public Schools Secondary Approved Reading List

Spokane Public Schools Secondary Approved Reading List Book Title Last Name First Name Level Approval Date "1776" kidsdiscover.com 8 1984 Orwell George H/M 1,000,000 Delinquents Fine Benjamin H 101 SummerJobs Ashley Roberta H 1920s: Rhetoric or Reality?, The Traverso Edmund H Halsey Van R. 1973 Consumer Buying Guide Teeman Lawrence M 1973 Who’s Who in Baseball Elias Sports Bureau (pub.) M 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke Arthur C. H/M 51st Dragon, The Brown Margaret H 6 X 8 Heinlein Robert A. H A is for Andromeda Hoyle Fred H Elliot John A Stone, A Leaf, A Door Wolfe Thomas H Abandoners, The Thomas Cottle H A-B-Cs of Aluminum, The Reynolds Metals Company M (pub.) Abdullah and His Two Strings Hukk Jane H Abe Lincoln Gets His Chance Cavanah Frances M Abe Lincoln in Illinois Sherwood Robert E. H Abie's Irish Rose Nichols Anne H Abigail Adams, Leading Lady Criss Mildred H Able McLaughlins, The Wilson Margaret H Abo Simbel MacQuitty William M Abolitionist Paper Garrison W.L. H About Atomic Power for People Rodlauer Edward & Ruth M About Caves Shannon Terry M About Checking Accounts Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Glasses for Gladys Ericsson Mary Kentra M About Insects That Help Plants Gibson Gertrude M About Jack’s Dental Checkup Jubelier Ruth M About Law Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Life Insurance Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Man's Economic Wants Gersting John, et al. H About Ready-to-Wear Clothes Shannon Terry M About Silkworms and Silk Wormser Sophie M About the American Economy Guyston Percy H About the U.S.Market System Gersting John, et al. -

Literature from Romance to Realism

THIRD EDITION Young Adult LITERATURE FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM MICHAEL CART CHICAGO | 2016 www.alastore.ala.org ADVISORY BOARD Robin Kurz, Assistant Professor, Emporia State University Stephanie D. Reynolds, Director, McConnell Center/Conference for the Study of Youth Literature, and Lecturer, School of Information Science, University of Kentucky Mary Wepking, Senior Lecturer, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee © 2016 by the American Library Association Extensive effort has gone into ensuring the reliability of the information in this book; however, the publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. ISBNs 978-0-8389-1462-5 (paper) 978-0-8389-1475-5 (PDF) 978-0-8389-1476-2 (ePub) 978-0-8389-1477-9 (Kindle) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Cart, Michael, author. Title: Young adult literature : from romance to realism / Michael Cart. Description: Third edition. | Chicago : ALA Neal-Schuman, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016014835 (print) | LCCN 2016014881 (ebook) | ISBN 9780838914625 (print : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780838914755 (pdf) | ISBN 9780838914762 (epub) | ISBN 9780838914779 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Young adult fiction, American—History and criticism. | Young adult literature—History and criticism. | Teenagers—Books and reading—United States. | Teenagers in literature. Classification: LCC PS374.Y57 C37 2016 (print) | LCC PS374.Y57 (ebook) | DDC 813.009/ 92837—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016014835 Book design by Kimberly Thornton in the Proxima Nova and Adelle typefaces. Cover images: (top) © oneinchpunch/Shutterstock, Inc.; (bottom) © Marijus Auruskevicius/ Shutterstock, Inc. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the United States of America 20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1 www.alastore.ala.org Contents Preface | ix PART ONE THAT WAS THEN 1 From Sue Barton to the Sixties ...................................... -

Discursive Construction of the Ideal Girl in 20Th Century Popular American Girls' Series by Kate Ha

“Too Good to Be True”: Discursive Construction of the Ideal Girl in 20th Century Popular American Girls' Series by Kate Harper A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2013 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Georganne Scheiner Gillis, Chair Heather Switzer Lisa Anderson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the discursive construction of the trope of the ideal girl in popular American girls' series in the twentieth century. Girls' cultural artifacts, including girls’ literature series, provide sites for understanding girls' experiences and exploring girlhood itself as a socially constructed identity, yet are often overlooked due to their presumed insignificance. Simple dismissal of these texts ignores the weight of their popularity and the processes through which they reach such status. This project challenges the derisive attitude towards girls' culture and begins with the assumption that these cultural texts do ideological work and therefore require consideration. The dissertation traces the development of the ideal and non-ideal girl over time, taking into account the cultural, political, and economic factors that facilitate the production of the discourses of girlhood. I include analysis of texts from six popular American girls' series as primary texts; visual elements or media productions related to the series; and supporting historical documents such as newspapers, "expert" texts, popular parents' and girls' magazines, film; and advertising. Methodological approach incorporates elements of literary criticism and discourse analysis, combining literary, historical, and cultural approaches to primary texts and supporting documents to trace the moments of production, resistance, and response in the figure of the ideal girl.