Human Enhancement in Performative Cultures by Andy Miah, Phd University of the West of Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T7lb Ilh W=1~ IA F I

L;L 7 T7lb Ilh W=1~ IA F I NEWSPAPER OF THE UNDERGRADUATES_ OF THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE__ OF TECHNOLOGY .V0L. LXXX No. 18I8 CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS, FRIDAY, APRIL 29, 1960 $ Cents Dorm tories and Fraternitzes s Drs. Wiesner, Luris of MIT Elected To !iPlan Full and Festive Weekerads National Academy of Sciences; Total Now 36 The apex of the Tech social season will come on May 6 and 7 with the IFC Two of MIT's most distinguished faculty members have just been elected to membership in the National Acad- and Dormitory Weekends. All Tech students are invited by Henry McCCarl, Co- emy of Sciences, the highest honor in American science. `Chairman of the Dorm Weekend, and Bob Dulsky, Chairman of the IF(C Week- The new members are Dr. Jerome B. Wiesner, dilrector of thle Research Laboratory of Electronics, and Dr. Sal- ,end to bring their dates and have "an especially good time." vador E. Luris, international authority on viruses and genetics. Dorm Weekend begins on Friday night, May 6, with cocktail paarties in With their election, MIT now has a total of 36 faculty and corporation member s who are members of the Nation- Talbot Lounge in East Campus. A semi formal dance will highlight the eve- al Academy. ning in The Parker House, spirited by music from the lively Jerry Daviss Combo. Dr. Wiesner received his doctoral degree in 1950 flrom the Univelrsity of Michigan, where he assisted in devel- Saturday afternoon, students and their dates are invited to attend a Beach oping modern electronic techniques for speech correction. -

The Simplicity and Complexity, Accuracy and Fuzziness of Sport Technology Xiang Yunping Zhoukou Normal University,Henan,China,466000

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 164 8th International Conference on Manufacturing Science and Engineering (ICMSE 2018) The simplicity and complexity, accuracy and fuzziness of Sport technology Xiang yunping Zhoukou Normal University,Henan,China,466000 Keywords: simplicity and complexity, accuracy and fuzziness Abstract. With the improvement of tennis technology in China, it is necessary to study the composition of its technology philosophically. This article attempts to make a preliminary discussion on some aspects from the simplicity and complexity, accuracy and fuzziness of natural dialectics category of tennis technique, to improve the knowledge of the nature and law of tennis technology from the philosophical point of view ,and also provide the philosophical basis for the improve the level of tennis. 1、The acquaintance of these two categories The development of tennis is a process from simple to complex, continuous improvement and perfection. From the development of tennis technology, the process has been experienced from simple technology to complex technology, from single tactics to comprehensive and changeable tactics. From the theory of tennis movement, it not only has experienced from simple to complex, from fuzzy to precise, but also experienced the process of describing tennis movement from complexity to simplicity, from precision to vagueness. In order to understand complex things, phenomena and processes, it is essential to break them down into simple elements or parts before they can be recognized. This is the simplicity principle. Because the elements of a complex system are not simple combinations, there are complex networks of interconnections and constraints. Therefore, you must be studied the integrity and complexity of the system. -

Deciding Who Is the Best Validity Issues in Selections and Judgements in Elite Sport

Deciding who is the best Validity issues in selections and judgements in elite sport Annika Johansson Department of Education Umeå 2010 DECIDING WHO IS THE BEST Validity issues in selections and judgements in elite sport ANNIKA JOHANSSON Department of Education UMEÅ UNIVERSITY Nr 95 • 2010 © Annika Johansson, 2010 Deciding who is the best. Validity issues in selections and judgements in elite sport. (Academic dissertation). Department of Education, Umeå University Sweden Printed by: Print & Media, Umeå University, May, 2010: 2008243 Paper: Cover: Silk 280g Insert: CT Natural 100g Cover photos: Acroski & Alpine skiing: Nisse Schmidt, Rhythmical gymnastics: Maria Edstrand, Soccer: Bildbyrån ISBN 978-91-7264-979-8 ISSN 0281-6768 Johansson, Annika. (2010). Deciding who is the best. Validity issues in selections and judgements in elite sport. Academic dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, Umeå University, Sweden, 2010. ISBN: 978-91-7264-979-8; ISSN: 0281-6768 Abstract This thesis is about selection processes and processes of measuring and judging athletes in compe- titions in top-level sport. The purpose was to increase the knowledge of these processes and to analyse them from a validity perspective in order to contribute to the discussion of whether the “right” athletes are selected to participate in teams, competitions and games and whether the “right” athletes win. The rule and judging systems were investigated in the judged sports acroski and rhythmic gymnastics. Information was gathered through individual interviews with two judges, two coaches, and four elite athletes from each of the sports, and in addition to this the respective sport’s rule systems, judging manuals, meeting protocols and historical documents were studied. -

Vdr # Name Name2 Dba 7067 Auto Electric Services Co

VDR # NAME NAME2 DBA 7067 AUTO ELECTRIC SERVICES CO INC 8523 BENNETT'S CARPETS, INC 940 HARTFORD STEAM BOILER 9727 HELEN MILLER BOWLES 9220 JEANNA SLUSHER 9561 JESSICA MADDOCKS 1690 KY NASP FOUNDATION 9093 LESLIE CELESTE HACKNEY 8746 100% EDUCATIONAL VIDEOS 7472 127 SOCCER CONFERENCE TOLIVER EL 3261 2008 KLA/SELA CONFERENCE 9739 4 T'S INC 6457 4/J ENTERPRISES INC 10187 4-C 10187 4-C 10187 4-C 10187 4-C 6011 4IMPRINT 7651 4SIGHT LEARNING 10124 555 PRODUCTIONS INC 7816 A & A SAFETY 12 A & J SERVICE CENTER 7300 A & J'S SONS CONSTRUCTION, INC 8257 A D TROPHY 9693 A PLUS LAWN & LANDSCAPE 2228 A T & T 2228 A T & T 2228 A T & T 2228 A T & T 2228 A T & T 2228 A T & T 6397 A T & T 8400 A T & T 8400 A T & T 22288 A T & T 7980 A T & T CONNECTIVITY SOLUTIONS 8400 A T & T CONNECTIVITY SOLUTIONS 2228 A T & T MOBILITY 7754 A T & T WIRELESS 8680 A W PELLAR & ASSOC INC 8174 A&E HOME VIDEO 8174 A&E HOME VIDEO 8174 A&E HOME VIDEO 8716 A. DAIGGER & COMPANY INC 7537 A+ QUALITY PRESSURE WASHING 6239 A-1 AUDIO VISUAL 8332 A-1 PORTABLE BUILDINGS 9974 AACER FLOORING, LLC 7535 AAEC 6899 AAP PUBLICATIONS / CHILD CARE BOOK 9156 AARON HARVEY 122 AASA 122 AASA 122 AASA 122 AASA 9947 AASPA AMERICAN 7140 AATF 7140 AATF - JAYNE ABRATE,EXEC DIR 3438 A-B ROOFING CO INC 8591 ABC 110 ABC SCHOOL SUPPLY INC 8419 ABC SUPPLY CO INC 9214 ABC TEACH 7020 ABC-CLIO INC 6357 ABDO PUBLISHING CO 7562 ABELL & ATHERTON EDUCATIONAL 7116 ABG PETROLEUM CONTRACTORS LLC 2331 ABILITATIONS 5164 ABILITATIONS 5164 ABILITATIONS 5164 ABILITATIONS 5164 ABILITATIONS/INTEGRA 3042 ABLENET INC 8721 ABNET -

Volume 129, Number 42

MIT’s Oldest and Largest The Weather Today: Sunny, 66°F (19°C) Newspaper Tonight: Cloudy, 53°F (12°C) Tomorrow: Rainy, 67°F (19°C) Details, Page 2 http://tech.mit.edu/ Volume 129, Number 42 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, October 6, 2009 All-Sorority ’13 Council Elected Next House Residents By Meghan Nelson STAFF REPORTER The Undergraduate Association Bemoan Teeny Meals released the results, but not the indi- vidual vote tallies, of its fall Senate Many Complain Food Is Worse, Portions Shrank and 2013 Class Council elections on Saturday. A little over a quarter of un- By Robert McQueen dergraduates voted. Danielle A. Class ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR and Amanda C. David were elected It all started on September 20, President and Vice President, respec- with a third of an ear of corn, snap tively, of an all-female, all-sorority peas, and a stuffed portabello mush- Class of 2013 Council. In a special room. Sean Y. Liu ’10 was disgusted election, Sojung C. Lee was elected with the size of his dinner, so he took Class of 2011 treasurer. a snapshot and sent it out the next-fo- Twenty-eight senators were also rum mailing list for everyone to see. elected. Nine were write-ins. All can- Within minutes, Liu’s e-mail had didates for senator who officially reg- prompted a chorus of complaints istered with the UA before the dead- about Next Dining, and about how it line were elected. has deteriorated since last year. The eight-member 2013 Class “A portion that can feed us last SEAN Y. -

Honor Roll Industries Drainage: ACO Sport Ten Hard-Court Projects at Centers of Hitting Walls: Bakko Bak Bords Courts: 12 Education That Easily Made the Grade

TennisIndustry ^ Hudsonville High DISTINGUISHED FACILITY-OF-THE-YEAR AWARDS School COURT CONSTRUCTION Hudsonville, Mich. Nominated by: GMB Architecture + Engineering Architect/Engineer: GMB Architecture + Engineering Surface: California Sports Surfaces Posts, Nets, Windscreens: Douglas Honor Roll Industries Drainage: ACO Sport Ten hard-court projects at centers of Hitting Walls: Bakko Bak Bords Courts: 12 education that easily made the grade. Completed: May 2016 By Peter Francesconi > Seven old asphalt courts were removed from the Hudsonville High School campus ll 10 outdoor hard-court winners of the Tennis Industry/ as part of a parking lot expansion, and a American Sports Builders Association’s Distinguished Facility- new post-tensioned concrete tennis facility of-the-Year Awards are at schools or colleges—a positive sign as was constructed at a new location. The end administrators and school boards see the value of investing in result is the Silver Award Winner for outdoor tennis, and all its associated health benefits, for students. hard courts. The original plans called for 10 AEight of these impressive projects used post-tensioned concrete, resulting courts, but an additional two courts were in a longer-lasting base that requires less maintenance than asphalt. This trend added as funding became available. The continues to gain momentum throughout the sports construction industry. And, owner and contractor worked closely with in a sign that court owners and managers are realizing the value of using knowl- neighbors to be able to pour concrete start- edgeable builders, six of the 10 projects tapped the expertise of ASBA Certified ing at 4 a.m., to avoid the heat of the day Tennis Court Builders. -

Negotiating the Boundaries of Digital Technologies in Elite Tennis Vidya Subramanian, Marianne Noel, Harmony Paquin

Tweet, Set, Match: Negotiating the Boundaries of Digital Technologies in Elite Tennis Vidya Subramanian, Marianne Noel, Harmony Paquin To cite this version: Vidya Subramanian, Marianne Noel, Harmony Paquin. Tweet, Set, Match: Negotiating the Bound- aries of Digital Technologies in Elite Tennis. Science Technology and Society, SAGE Publications, In press, pp.097172182091292. 10.1177/0971721820912923. hal-02943069 HAL Id: hal-02943069 https://hal-upec-upem.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02943069 Submitted on 18 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Tweet, Set, Match: Negotiating the Boundaries of Digital Technologies in Elite Tennis VIDYA SUBRAMANIAN, MARIANNE NOEL and HARMONY PAQUIN This article attempts to examine the highest tier of elite tennis through a technological lens in order to understand the several imbrications of tennis and technology in Grand Slam events. Using qualitative and quantitative methods, this article studies the version of tennis that exists today—replete with RFID chips, screen interfaces, more powerful racquets than ever before and the ubiquity of social media. As the relationship between players and fans, organisers and visitors, and even gameplay and umpiring have evolved to allow the use of several technologies, Grand Slam tennis has embraced the era of social media and technologically mediated sport. -

Analysis Technology of Tennis Sports Match Based on Data Mining and Image Feature Retrieval

Hindawi Complexity Volume 2020, Article ID 8877161, 15 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8877161 Research Article Analysis Technology of Tennis Sports Match Based on Data Mining and Image Feature Retrieval Hong Huang and Risheng Deng School of Sports Science, Lingnan Normal University, Zhanjiang, Guangdong 524048, China Correspondence should be addressed to Risheng Deng; [email protected] Received 3 September 2020; Revised 25 September 2020; Accepted 30 September 2020; Published 14 October 2020 Academic Editor: Chuan Lin Copyright © 2020 Hong Huang and Risheng Deng. )is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Tennis game technical analysis is affected by factors such as complex background and on-site noise, which will lead to certain deviations in the results, and it is difficult to obtain scientific and effective tennis technical training strategies through a few game videos. In order to improve the performance of tennis game technical analysis, based on machine learning algorithms, this paper combines image analysis to identify athletes’ movement characteristics and image feature recognition processing with image recognition technology, realizes real-time tracking of athletes’ dynamic characteristics, and records technical characteristics. Moreover, this paper combines data mining technology to obtain effective data from massive video and image data, uses mathematical statistics and data mining technology for data processing, and scientifically analyzes tennis game technology with the support of ergonomics. In addition, this paper designs a controlled experiment to verify the technical analysis effect of the tennis match and the performance of the model itself. -

Guidebook to Applying Zenniz Game-Tracking Technology in Tennis Coaching

Guidebook to Applying Zenniz Game-Tracking Technology in Tennis Coaching Alina Petras Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in Sports and Leisure Management 2016 Author or authors Group or year of Alina Petras entry DPXII Title of report Number of Guidebook to Applying Zenniz Game-Tracking Technology in pages and Tennis Coaching appendices 40 Teacher(s) or supervisor(s) Markus Arvaja The purpose of this thesis was to create a product-based guidebook for tennis coaches in order to encourage and simplify the usage of Zenniz game-tracking technology in tennis coaching. The need for creating the guidebook emerged from the fast development in the field of sport technology and lack of material on applying accessible technological tools such as on-court data tracking systems in tennis coaching. The guidebook is limited to Zenniz game-tracking system as a tool, as it is the most used and available system in the target area, Finland. The report part of the thesis consists of recap on technologies present in the field of tennis, as well as analysis on performance indicators tracked by Zenniz system. The second part of the paper is Zenniz coaching guidebook itself. Keywords Tennis, Coaching, Technology, Performance, Development Table of contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2 Emerging technologies in tennis coaching ........................................................................ 4 3 Zenniz performance indicators .......................................................................................... -

INFOSYS TENNIS RADAR: the Next Big

INFOSYS TENNIS RADAR The Next Big Era CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 TENNIS EVENTS ADD FLAVOR 28 TENNIS IS ON THE VERGE OF A NEW ERA 6 ANALYTICS MEETS EXPERIENCE 31 THE TENNIS RADAR STUDY 8 ANALYTICS EXPERIENCE INDEX 33 THE BEST OF TIMES, THE MOST COMPLICATED OF TIMES 10 THE FUTURE OF TENNIS 40 ATP UPGRADES EXPERIENCE 12 FANS SEEK STORIES 41 COME FOR THE MATCH, STAY FOR THE EXPERIENCE 13 A NEW AUDIENCE FOR A NEW ERA 43 THE CLUB MODEL EVOLVES 14 TECH’S ROLE IN TENNIS’S NEXT BIG ERA 45 THE HIGH COST OF COMPETING 16 1. EXPERIMENT AT EVERY LEVEL 46 PLATFORM TECH: ANALYTICS GAME CHANGER 18 2. DEMOCRATIZE DATA AND ANALYTICS 47 A GAME FOR ALL, GROWING GLOBALLY 21 3. FOCUS ON THE SOCIAL ELEMENT 48 THE RIGHT RACKET MATTERS 22 4. PROTECT THE HUMAN ELEMENT 49 WATCHING COURTSIDE FROM YOUR COUCH 23 TECH SHOWS THE WAY 51 GAME, SET, MATCH: WINNING NEW TENNIS FANS 25 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 52 ADDING VIRTUAL REALITY 26 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 53 External Document © 2020 Infosys Limited INFOSYS TENNIS RADAR | 3 4 | INFOSYS TENNIS RADAR External Document © 2020 Infosys Limited EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 2019, the Infosys Knowledge Institute conducted a interviewees. All age groups in our survey answered worldwide study of tennis to answer the question, How can roughly the same regarding match length: 85% of the proud sport of tennis, with its rich tradition, continue Millennials and 84% of Generation Z, Generation X, to stay relevant and be even more successful in a rapidly and Baby Boomers said match length is just right. -

Udr 108 18.Pdf

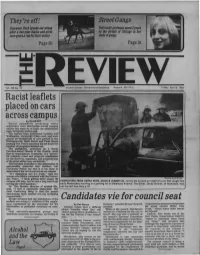

' They''re dlf! Delaware Park breaks out strong after a two-rear /Jiatus and gives race-g(!ers B1'111llor tl1eir money. PageBl' 1.1.1• :c --1~Vol. 108 No. 18 Student Center, University of De-law~re Newark, DE 19716 Friday, April6, 198.C Racist leaflets placed on cars across campus by David Sill Racist pamphlets preaching white supremacy were distributed across campus earlier this week by at least one unidentified man, UniverSity police said. The leaflets were distributed Tuesday and Wednesday, University Police said, and were placed on windshields of cars parked in the Hollingsworth, Main Street and Field House parking lots. Police said they did not know the number of pamphlets handed out. The pamphlets, published by a North Carolina-based Church of the Creator, state that its organization, Creativity, is a "power ful religious creed and program established for the survival, expansion, and advancement of the great white race, exclusively." This incident is similar to the distribution of anti-semitic material last October, but University Police say that it is too early to determine if the two occurr.ences are related. "It's disgusting and it's trash," said one woman who filed a complaint with the Univer sity Police. "I think getting these peaple off campus will help, but we are a long way from FI~EfiGHTERS FROM AETNA HOSE, HOOK & LADDER CO. su.rvey the burned-out shell of a car that caught fire solving the whole pr.oblem." early Wednesday morning in a parking lot on Delaware Avenue. The driver, Sandy Grimes, of Hockessin, was Dr. -

Usta Jr. Team Tennis Texas Section Summer Championships

* WHAT’S HOT? WHAT’S COOL FOR THE PROS? THUNDER RIP AIR VANQUISH LIQUIDMETAL 4 O 3 WHITE $79.99 SAVE $140 $79.99 SAVE $50 $79.99 SAVE $120 $199.99 245735; Orig. $219.99 244794; Orig. $129.99 246420; Orig. $199.99 247151 Used by Maria Sharapova LIQUIDMETAL RADICAL nVISION TRIAD T4 FLEXPOINT RADICAL $79.99 SAVE $100 $99.99 SAVE $60 $79.99 SAVE $120 $179.99 247501; Orig. $179.99 242022; Orig. $159.99 246129; Orig. $199.99 242969 Used by Andre Agassi nPS95 nTOUR n5 nSIX-ONE TOUR $99.99 SAVE $50 $119.97 SAVE $60 $99.99 SAVE $100 $179.99 242019; Orig. $149.99 242030; Orig. $179.99 246130; Orig. $199.99 239463 Used by Roger Federer ARE YOU A TEACHING PRO? Tennis Shoe Blowout $ Reebok Team Join Golfsmith’s Pro Rewards 19.98 Tennis Apparel Save Up To 50% Program and receive: Start earning points towards FREE golf and tennis 243023 stuff when you enroll in our FREE Pro Rewards Program. For every student you refer to us, CROSSFIRE 2 SHOES 243008 you receive one point for every dollar they Select from $69.99 SAVE $30 spend using their referral card. 249740; Orig. $99.99 8 Styles In Sign up today at 8 Exciting golfsmith.com/rewards T7 SHOES Colors For $49.99 SAVE $50 Men and 245491; Orig. $99.99 Interested in Receiving our 68 Page Tennis Catalog? Women! Orig. $30-$43 Be the first to receive the largest, most comprehensive CLIMAULTIMATE II tennis catalog ever created, featuring over 68 pages of $49.99 SAVE $50 the latest tennis technology, apparel and accessories.