M. Stephen Returning to Original Form; a Central Dynamic in Balinese Ritual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

Mythologies of the Indian Goddess in Sex

Vol-6 Issue-5 2020 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 Matrix—Copulating and Childless: Mythologies of the Indian Goddess in Sex Suwanee Goswami* and Dr. Eric Soreng** *Research Scholar Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi **Assistant Professor Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi ABSTRACT The paper on Matrix is a Jungian oriented mythological research on the Indian Goddess. ‘Goddess in sex’ means that She is fertile and in copulation but Her womb—Matrix—never bears fruits. Her copulation does not consummate in conception because the gods prevent it. She is married and as wife copulates to conceive, but only becomes Kumari-Mata, the Virgin Mother, in Her various manifestations and beget offspring parthenogenetically. She embodies not only maternal love but also encompass intense sexual passion as well as profound spiritual devotion; Her fertility fructifying into ascetical and spiritual wisdom. Such is the mythological series of Goddess Parvati. Her mythologies are recollected and rearranged to form a structural whole for reflection and interpretation wherever possible. The paper consummates with the mythic images of the primacy of the Sacred Feminine in India. Key Words: Matrix, Goddess Parvati, Goddess Kali Carl Jung (1981) defines the Matrix as “the form into which all experience is poured”. He conceptualized the Collective Unconscious as the mother, the source of psychic life and all the manifestations of the psyche. In the lifespan development overcoming the impediments in the world outside that obstructs man’s ascent liberates him from the mother and that leaves in him an eternal thirst which makes him return back to drink renewal from the source of psychic energy and life. -

'Pashupata' to 'Shiva'

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2017; 3(11): 233-236 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal ‘Pashupata’ to ‘Shiva’: The Journey of a ‘Nature God’ Peer Reviewed Journal Refereed Journal to a ‘Supreme Vedic Deity’ Indexed Journal UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 Satendra Kumar Mishra e-ISSN: 2454-6615 Abstract Satendra Kumar Mishra As per the Puranas, the transformation of Pashupata to Vedic Rudra and finally to Shiva was a slow Assistant Professor process of shifting culture closely interacting with each other. On critical analysis it is observed that it Amity School of Languages Amity University, Lucknow happened due to the multiplicity of belief systems attached to Shiva by all the ideologically same but Campus, India different distinct sects who worshipped him. It is to be noted that the different sects took the same Pashupata in remarkably different ways thereby assigning different ideological identities to Pashupata and Rudra, and even then there is only one Shiva. Keywords: Pashupata, Rudra, Vedic, Shiva Introduction Objective In this research, I worked on two basic points First, working on the fact that the term „Pashupata‟ has few common features in all „Shaivite‟ cults but at the same time has few features which are different between them. In the later decades these different features got entangled with each other and all branches of „Pashupata‟ and „Rudra‟ were taken to be same. Second, It is an amalgamation of the different cults of Shiva which needs extensive research to bring forward more knowledge to identify the differences between Rudra, Pashupata and the transformed Shiva. -

A New Research Paper Turns the General Perception of Brahman and Shudra Upside Down

A new research paper turns the general perception of Brahman and Shudra upside down A new scholarly and practical interpretation of Bhagvadgita with a joint effort of a Sanskrit scholar and an accomplished US based scientist turns the entire premise of shudra as a servant class upside down. In fact, the article suggests that it is the natural duty of the other so called upper castes to serve the society, including shudra with distinctions of their required qualities and action. The lead author of th recently published peer-reviewed article in Prachi Prajna journal, Dr. Aparna Dhir Khandelwal, said that this new simple revelation will have enormous impact on the modern society, not only in India but perhaps the entire world. It is because what is stated in dharma granthas applies to the humanity, not just Indians, although it will certainly begin from here. What the researchers discovered is that there is a word ‘shudrashyapi‘ that has been either misinterpreted or ignored over the centuries, or at least has not been emphasized by Indian as well International scholars. Even Adi Shankaracharya misses the point, according to the publication entitled ” ” (Appropriate analysis of the definition of shudra in Bhagvadgita). Few of such statements listed below – 1. Sri Adi Shankaracharya of Advaita Sampradaya – ‘Industrious service to the other three classes for fair recompense is the duty of sudras the worker class. Only one service was ordained for sudras the worker class and that was to ungrudgingly serve the three upper social orders.’ 2. Sri Madhvacharya of Brahma Sampradaya – ‘The duties of sudras is loyal service to the other three classes and receiving sustenance for their livelihood from them and is born of the nature of tama guna.’ 3. -

Kali, Untamed Goddess Power and Unleashed Sexuality: A

Journal of Asian Research Vol. 1, No. 1, 2017 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/jar Kali, Untamed Goddess Power and Unleashed Sexuality: A Study of the ‘Kalika Purana’ of Bengal Saumitra Chakravarty1* 1 Post-Graduate Studies in English, National College, Bangalore, India * Saumitra Chakravarty, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to analyse the paradox inherent in the myth of Kali, both in her iconic delineation and the rituals associated with her worship as depicted in the twelfth century Kalika Purana. The black goddess Kali breaks conventional stereotypes of feminine beauty and sexuality in Hindu goddess mythology. She is the dominant sexual partner straddling the prone Siva and the wild warrior goddess drinking demon blood. She is originally depicted as a symbol of uncontrolled fury emerging from the fair, beautiful goddess Ambika in the battle with the demons in older goddess texts. Thereafter she gains independent existence both as the dark, mysterious and sexually demanding version of the more benign and auspicious Parvati and the Primordial Goddess Power pre-dating the Hindu trinity of male gods, the Universal Mother Force which embraces both good and evil, gods and demons in the Kalika Purana. Unlike other goddess texts which emphasize Kali’s role in the battle against the demons, the Kalika Purana’s focus is on her sexuality and her darkly sensual beauty. Equally it is on the heterodoxical rituals associated with her worship involving blood and flesh offerings, wine and the use of sexual intercourse as opposed to Vedic rituals. Keywords kali, female, sexuality, primordial, goddess, paradox 1. -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 97 TO BE ANSWERED ON 25.4.2016 VAISAKHA 5, 1938 (SAKA) NATIONAL HERITAGE STATUS 97. SHRI B.V.NAIK; SHRI ARJUN LAL MEENA; SHRI P. KUMAR: Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has finalized its proposal for sending its entry for world heritage status long with the criteria to select entry for world heritage site status; (b) if so, the details thereof along with the names of temples, churches, mosques and monuments 2Iected and declared as national heritage in various States of the country, State-wise; (c) whether the Government has ignored Delhi as its official entry to UNESCO and if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefor; (d) whether, some sites selected for UNESCO entry are under repair and renovation; (e) if so, the details thereof and the funds sanctioned by the Government in this regard so far, ate-wise; and (f) the action plan of the Government to attract more tourists to these sites. ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE, CULTURE AND TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) AND MINISTER OF STATE, CIVIL AVIATION (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a) Yes madam. Government has finalized and submitted the proposal for “Historic City of Ahmedabad” as the entry in the cultural category of the World Heritage List for calendar year 2016-17. The proposal was submitted under cultural category under criteria II, V and VI (list of criteria in Annexure I) (b) For the proposal submitted related to Historic City of Ahmedabad submitted this year, list of nationally important monuments and those listed by Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation are given in Annexure II. -

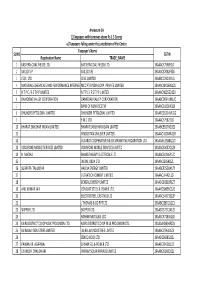

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

Shaivism by Dr

Shaivism By Dr. Subhash Chandra Shaivism is one of the major traditions within Hinduism that reveres Shiva as the Supreme Being. The followers of Shaivism are called "Shaivites" or "Saivites". It is one of the largest sects that believe Shiva — worshipped as a creator and destroyer of worlds — is the supreme god over all. The Shaiva have many sub-traditions, ranging from devotional dualistic theism such as Shaiva Siddhanta to yoga-oriented monistic non-theism such as Kashmiri Shaivism. It considers both the Vedas and the Agama texts as important sources of theology. The origin of Shaivism may be traced to the conception of Rudra in the Rig Veda. Shaivism has ancient roots, traceable in the Vedic literature of 2nd millennium BCE, but this is in the form of the Vedic deity Rudra. The ancient text Shvetashvatara Upanishad dated to late 1st millennium BCE mentions terms such as Rudra, Shiva and Maheshwaram, but its interpretation as a theistic or monistic text of Shaivism is disputed. In the early centuries of the common era is the first clear evidence of Pāśupata Shaivism. Both devotional and monistic Shaivism became popular in the 1st millennium CE, rapidly becoming the dominant religious tradition of many Hindu kingdoms. It arrived in Southeast Asia shortly thereafter, leading to thousands of Shaiva temples on the islands of Indonesia as well as Cambodia and Vietnam, co- evolving with Buddhism in these regions. In the contemporary era, Shaivism is one of the major aspects of Hinduism. Shaivism theology ranges from Shiva being the creator, preserver, destroyer to being the same as the Atman (self, soul) within oneself and every living being. -

The Word “Rudraksha” Is Derived from Rudra (Shiva—The Hindu God of All Living Creatures) and Aksha (Eyes)

The word “Rudraksha” is derived from Rudra (Shiva—the Hindu god of all living creatures) and aksha (eyes). Hindu legends and some holy Books in HINDUISM Like SHIVAPURANAS says that once Lord Shiva opened His eyes after a long period yogic meditation, and because of extreme fulfillment He shed a tear. This single tear from Shiva’s eye grew into the rudraksha tree. It is believed that by wearing the rudraksha bead one will have the protection of Lord Shiva. Rudraksha is a Sanskrit word made of Rudra + Akasha or in English "Rudra's eyes" means the aksha or tears of lord rudra or shiva, is a seed is traditionally used for prayer beads in Hinduism and Buddhism. The seed is produced by several species of large evergreen broad-leaved tree in the genus Elaeocarpus, with Elaeocarpus ganitrus being the principal species used in the making of organic jewellery or mala. Rudraksha beads are a plant product, containing carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and trace elements in combined form. The percentage compositions of their gaseous elements was determined by C-H-N Analyzer and by Gaschromatography. The result shows that Rudraksha beads consist of 50.031 % carbon, 0.95% nitrogen, 17.897% hydrogen and 30.53% oxygen. Rudraksha is a large evergreen broad-leaved tree. Its scientific name being ELAEOCARPUS GANITRUX ROXUB, the family is TILLIACEAE. Altitude-wise, its habitat starts from sea-coast and goes up to 2,000 meters. Geographically it is found growing naturally and abundantly in tropical and subtropical areas. The trees are perennial in habitat. The trees are almost 50ft to 200ft in height Common Name: Sanskrit, Hindi & Marathi : Rudraksha Bengali: Rudrakaya Kannada: Rudrakshi Tamil: Akkamrudrakai Telugu: Rudraksha Halu English: Woodenbegar According to old mythology " Siva Purana" that the favorites of Lord Siva , Rudraksha trees grow in Gouda Land which in present era is the area of the Gangetic Plain on the southern border area of Asia to the foothills of great Himalaya and middle area of Nepal. -

(N Ear Sadar BDO Office), Jalpaiguri-735101

Short Listed Candidates for Computer Proficiency Test & Interview for the post of Data Entry Operator for District Hospital & Block Level Hospital, Jalpaiguri District Date of Exam : 12-02-2014 Time : 10:00 AM Examination Sl. No. Roll No. Name Father Address Venue 84, Panda Para Colony, Goli No. - 5, PO.+Dist. Jalpaiguri, 1 BD-5 Sanjoy Sarkar Bijoy Kumar Sarkar 735101 Belakoba, Vivekananda Colony, PO. Prasanna Nagar, 2 BD-9 Dipayan Sarkar Dilip Sarkar Dist.Jalpaiguri - 735133 3 BD-11 Dipanjan Das Dipak Das Mohuri Para, PO.+Dist.Jalpaiguri -735101 Vill. Kawakhali, PO. Sushruta Nagar, PS. Matigara, 4 BD-15 Samrat Sarkar Sanatan Sarkar Dist.Darjeeling, 734012 5 BD-28 Avishek Ghosh Anup Kumar Ghosh Ananda Para (Extension), PO.+Dist.Jalpaiguri, 735101 6 BD-30 Tanumay Dey Ganesh Chandra Dey West Kerani Para, Po.+Dist. Jalpaiguri, 735101 Vill. 1 No. Baikur Gour Gram, PO. Helapakri, PS. Maynaguri, 7 BD-39 Nibedita Roy Dwijen Roy Dist. Jalpaiguri, 735305 C/o. Sukesh Banerjee, Vill.+PO. Bholardabri, Near 8 BD-41 Tubai Sanyal Sri Kartick Sanyal Ramthakur Mandir, PS. Alipurduar, Dist. Jalpaiguri, 736123 Indira Gandhi Colony, 4th By Lane, PO. Denguajhar, Dist. 9 BD-43 Amit Malakar Prabhat Malakar Jalpaiguri, 735121 10 BD-58 Pankaj Paul Nripen Paul Vill+P.O. Debnagar Dt- Jalpaiguri - 735102 11 BD-61 Abhishek Dey Ajit Kr. Dey Old Police Line Para, Po.+Dist. Jalpaiguri, 735101 12 BD-65 Prasenjit Barua Ashok Barua Old Hasimara, Po. Hasimara, Dist. Jalpaiguri, 735215 13 BD-70 Uttam Kr Roy Nripendra Nath Roy Vill.+PO. Satkura, Dist. Jalpaiguri, 735122 C/o. Ranjit Sarkar, South Colony, Behind Buddha Mandir, 14 BD-72 Ajay Dey Hemendra Dey PO. -

Shri Shiva Rahasya

SHIVA RAHASYA C SHRI SHIVA RAHASYA (THE SECRET TEACHING OF SHIVA) 1 SHIVA RAHASYA In the Name of Shiva, the Most Glorious, the Most Obvious, the Highest God, Master of the Universe, Lord of Yoga, Lord of Unity To the Eternal Teacher and Master, Obeisance. May He Enlighten the heart of all Seekers And set their purified mind upon that Path which is straight and not crooked! May He forever guide us From Delusion unto Truth, From Darkness unto Light, From Death unto Eternal Life. SHRI SHIVA RAHASYA (THE SECRET TEACHING OF SHIVA) being THE GLORIOUS MYSTERY OF SUPREME REALITY according to HIS DIVINE HOLINESS MAHAGURU SHRI SOMA-NATHA MAHARAJ DEV with Abridged commentary by Shri Somananda Copyright © 2004-2006 The Yoga Order International 2 SHIVA RAHASYA THE FIRST LIGHT (Chapter One) 1 Wherein His Supreme Majesty Lord Shiva introduces the Eternal Teaching of Yoga to the Four Holy Seers Om is the Eternal Sound Supreme. Of that all other sounds are born. Thus spoke Sage Vyasa, the divinely appointed Compiler and Disseminator of Sacred Scriptures: 1. OM. Adoration be to Shiva, the Essence of all Goodness, the Kindly, the Pure, the All- Knowing, the All-Powerful, the Most Merciful One! 2. O you who have sought instruction in the Highest Truth! seek no more. For, I shall now speak to you the Word of God which was proclaimed for the deliverance of Souls from delusion, pain and sorrow. By hearing It men know what is right and tread upon the Path of Light. 3. Om is the Eternal Sound of Truth that ever abides in God's Heart. -

ICEESC-2021 Virtual Conference INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on EMERGING ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS and CONTROL

ICEESC-2021 Virtual Conference INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EMERGING ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS AND CONTROL 06TH & 07TH MAY 2021 VIRUDHUNAGAR ORGANIZED BY DEPARTMENT OF EEE, SETHU INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, VIRUDHUNAGAR (DISTRICT) IN ASSOCIATION WITH INSTITUTE FOR ENGINEERING RESEARCH AND PUBLICATION (IFERP) IICCEEEESSCC--22002211 Virudhunagar th th 06 - 07 May, 2021 Organized by: Department of EEE, Sethu Institute of Technology, Virudhunagar & Institute For Engineering Research and Publication [IFERP] Rudra Bhanu Satpathy Chief Executive Officer Institute For Engineering Research and Publication. On behalf of Institute For Engineering Research and Publications (IFERP) and in association with Sethu Institute of Technology, Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu, India. I am delighted to welcome all the delegates and participants around the globe to Sethu Institute of Technology, Virudhunagar, India for the “International Conference on Emerging Electrical Systems and Control (ICEESC-2021)” Which will take place from 06th - 07th May'2021 It will be a great pleasure to join with Engineers, Research Scholars, academicians and students all around the globe. You are invited to be stimulated and enriched by the latest in engineering research and development while delving into presentations surrounding transformative advances provided by a variety of disciplines. I congratulate the reviewing committee, coordinator (IFERP & SIT) and all the people involved for their efforts in organizing the event and successfully conducting the International Conference and wish all the delegates and participants a very pleasant stay at Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu, India Sincerely, Rudra Bhanu Satpathy Preface The International Conference on Emerging Electrical Systems and Control (ICEESC-21) is being organized by Department of EEE, Sethu Institute of Technology, Virudhunagar in Association with IFERP-Institute for Engineering Research and Publications on the 06th – 07th May, 2021.