Does Street Art Make Communities Better?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Article} {Profile}

{PROFILE} {PROFILE} {FEATURE ARTICLE} {PROFILE} 28 {OUTLINE} ISSUE 4, 2013 Photo Credit: Sharon Givoni {FEATURE ARTICLE} Street Art: Another Brick in the Copyright Wall “A visual conversation between many voices”, street art is “colourful, raw, witty” 1 and thought-provoking... however perhaps most importantly, a potential new source of income for illustrators. Here, Melbourne-based copyright lawyer, Sharon Givoni, considers how the laws relating to street art may be relevant to illustrators. She tries to make you “street smart” in an environment where increasingly such creations are not only tolerated, but even celebrated. 1 Street Art Melbourne, Lou Chamberlin, Explore Australia Publishing Pty Ltd, 2013, Comments made on the back cover. It canvasses: 1. copyright issues; 2. moral rights laws; and 3. the conflict between intellectual property and real property. Why this topic? One only needs to drive down the streets of Melbourne to realise that urban art is so ubiquitous that the city has been unofficially dubbed the stencil graffiti capital. Street art has rapidly gained momentum as an art form in its own right. So much so that Melbourne-based street artist Luke Cornish (aka E.L.K.) was an Archibald finalist in 2012 with his street art inspired stencilled portrait.1 The work, according to Bonham’s Auction House, was recently sold at auction for AUD $34,160.00.2 Stencil seen in the London suburb of Shoreditch. Photo Credit: Chris Scott Artist: Unknown It is therefore becoming increasingly important that illustra- tors working within the street art scene understand how the law (particularly copyright law) may apply. -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

2021 Cityarts Grantees

2021 CITYARTS GRANTEES 2nd Story Chicago Jazz Philharmonic 3Arts, Inc. Chicago Kids Company 6018North Chicago Maritime Arts Center A.B.L.E. - Artists Breaking Limits & Expectations Chicago Media Project a.pe.ri.od.ic Chicago Public Art Group About Face Theatre Collective Chicago Shakespeare Theater Access Contemporary Music Chicago Sinfonietta Africa International House USA Chicago Tap Theatre Aguijon Theater Company Chicago West Community Music Center American Indian Center Chicago Youth Shakespeare Apparel Industry Board, Inc. Cinema/Chicago Art on Sedgwick Clinard Dance Arts Alliance Illinois Collaboraction Theatre Company Arts & Business Council of Chicago Collaborative Arts Institute of Chicago Arts of Life, Inc. Community Film Workshop of Chicago Asian Improv aRts: Midwest Community Television Network Avalanche Theatre Constellation Men's Ensemble Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture Contextos Beverly Arts Center Court Theatre Beyond This Point Performing Arts Association Crossing Borders Music Black Alphabet Dance in the Parks, NFP Black Ensemble Theatre DanceWorks Chicago Black Lunch Table D-Composed Gives Cedille Chicago, NFP Definition Theatre Company Cerqua Rivera Dance Theatre Design Museum of Chicago Changing Worlds Erasing the Distance Chicago a cappella Fifth House Ensemble Chicago Architecture Foundation Filament Theatre Ensemble Chicago Art Department Forward Momentum Chicago Chicago Arts and Music Project Free Lunch Academy Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education Free Spirit Media Chicago Balinese Gamelan Free Street Theater Chicago Blues Revival FreshLens Chicago Chicago Cabaret Professionals Fulcrum Point New Music Project Chicago Childrens Choir Garfield Park Conservatory Alliance Chicago Composers Orchestra Global Girls Inc. Chicago Dance Crash Goodman Theatre Chicago Dancemakers Forum Guild Literary Complex Chicago Filmmakers Gus Giordano's Jazz Dance Chicago, Inc. -

PRESERVATION of STREET ART in PARIS. an EXAMPLE for RIGA? Quentin-En-Yvelines, Fra Latvian Academy of Cult

Mg.sc.soc. Valērija Želve Alumna, Université de Versailles Saint- Quentin-en-Yvelines, France, Latvian Academy of Culture PRESERVATION OF STREET ART IN PARIS. AN EXAMPLE FOR RIGA? Mg. sc. soc. Valērija Želve Alumna, Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France, Latvian Academy of Culture Abstract In many cities graffiti and street art is considered as vandalism and is often connected with crime. However, in some cities majority of the population does not agree with such a statement. They see street art and graffiti as decoration of the city. They think the artists deserve a safe space for expressing themselves. It is already a little step towards preserving the street art movement, as, of course, not all the citizens will share this opinion, since place of street art is still a very arguable question in many cities around the world. More and more organisations, associations and projects of different types are being created to promote and protect the urban art. Promotion of street art can be expressed in different ways, for example, panel discussions and workshops, exhibitions and festivals. Several street art and graffiti related spaces are being opened in Paris. Museums, warehouses, walls, schools – every kind of space could be used as a platform for the artists. This is also a nice way to show to the city council how important this culture is to the citizens of Paris. At the same time Riga cannot be yet proud of a thriving street art and graffiti culture. But what if Riga actually took Paris as an example? Could similar organisations in Latvia improve the society’s attitude towards urban cultures? Could the safe platform for street art be a solution for its popularization in Riga? The aim of this paper is to introduce organisations which promote and protect street art and graffiti in Paris and to evaluate if street art positions in Paris could actually be an example for Riga. -

Street Art & Graffiti in Belgrade: Ecological Potentials?

SAUC - Journal V6 - N2 Emergence of Studies Street Art & Graffiti in Belgrade: Ecological Potentials? Srđan Tunić STAW BLGRD - Street Art Walks Belgrade, Serbia [email protected], srdjantunic.wordpress.com Abstract Since the emergence of the global contemporary graffiti and street art, urban spaces have become filled with a variety of techniques and art pieces, whether as a beautification method, commemorative and community art, or even activism. Ecology has also been a small part of this, with growing concern over our environment’s health (as well as our own), disappearing living species and habitats, and trying to imagine a better, less destructive humankind (see: Arrieta, 2014). But, how can this art - based mostly on aerosol spray cans and thus not very eco-friendly - in urban spaces contribute to ecological awareness? Do nature, animal and plant motifs pave a way towards understanding the environment, or simply serve as aesthetic statements? This paper will examine these questions with the example of Belgrade, Serbia, and several local (but also global) practices. This text is based on ongoing research as part of Street Art Walks Belgrade project (STAW BLGRD) and interviews with a group of artists. Keywords: street art, graffiti, ecology, environmental art, belgrade 1. Introduction: Environmental art Art has always been connected to the natural world - with its Of course, sometimes clear distinctions are hard to make, origins using natural materials and representing the living but for the sake of explaining the basic principles, a good world. But somewhere in the 1960s in the USA and the UK, example between the terms and practices could be seen a new set of practices emerged, redefining environmental in the two illustrations below. -

Ideas Without Words Collage

Design Museum of Chicago 1917 N Elston Ave designchicago.org Chicago, Illinois 60642 1219 Great Ideas Poster Design Project Using collage and drawing techniques, create a poster that is inspired by a quote and represents what you value most about your community. Communicate your quote without words. Educational Goals • Build visual communication skills • Explain art and design work verbally to others • Grow understanding of composition • Apply limitations in a design project Materials list • Paper (multiple colors or single color will also work) • Stencil shapes (see last page of this PDF for printable shapes) • Highlighters/pencils/markers/crayons/pens • Scissors • Glue Design Museum of Chicago 1917 N Elston Ave designchicago.org Chicago, Illinois 60642 1219 — Phase 1: Collage Choose a quote. We've provided a few below, or choose your own favorite quote. You’ll be making a post- er that communicates your quote with shapes and lines only. Making a poster is like writing a story or speech. Before you start, answer these questions: · What is the message I want people to understand about the quote I selected when they look at my poster? · What will I show so they see what I mean? · How can I communicate without words? Keeping the answers to these questions in mind, create a collage that is inspired by the quote you chose. We've provided some shapes to get started, or you can make your own. Make as many versions of this as you please — there are no wrong answers or mistakes! — Phase 2: Drawing Next, you're going to create a continuous line drawing. -

When the Wall Talks: a Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move”

When The Wall Talks: A Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move” A Journal Paper Hasan IbnuSafruddin (0707848) English Education Department, Faculty of Language and Arts Education, Indonesia University of Education, Dr. Setiabudhi 229, Bandung 40154, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract: In Indonesia Graffiti phenomenon has become a popular culture. Graffiti exists around us; in public space, wall, and toilet.Its existence sometime lasts just a few days then beingerased, but some other exists for a long time. Some people think graffiti is a kind of vandalism, some other think it is a piece of art. That makes the graffiti interesting to me. The author believe there must be a purpose and meaning in creating graffiti. Bandung city is popular as the place of creative people; there are many communities of Bomber, graffiti creator called.The author choose some graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung as the sample for my analysis. Different with other graffiti, Act Move more applies more the words form rather than pictures. In this paper the author would like to analyze five graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung city through the Roland Barthes framework. Barthes‟ Frame work isapplied to find out the meaning of graffiti. After doing descriptive analysis of the graffiti the author also do an interview with the Bomber of Act Move to enrich the data and make the clear understanding of this study. The finding of this study is the meaning of denotation, connotation and myth or ideology of the graffiti. The author expect this study can give the exploration and interpretation the meaning beyond and surface of graffiti. -

Arquivototal.Pdf

Débora Machado Visini A CIDADE É O SUPORTE: arte urbana, mercado e subversão. Texto apresentado ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Artes Visuais da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito para obtenção de título de mestre. Linha de Pesquisa: Historia, Teoria e Processos de Criação em Artes Visuais. Orientadora: Prof. Dr. Maria Helena Magalhães João Pessoa Fevereiro, 2017 AGRADECIMENTOS Existe uma família afetuosa, composta por milhares de pessoas que vão passando pelas nossas vidas. Alguns permanecem, outros se vão. Essa família não significa hereditariedade sanguínea, mas sim ancestralidade, aqueles vínculos e conexões que sentimos e que, no entanto não sabemos explicar direito de onde vem e como vem. Gostaria de agradecer a essa família afetuosa. Em primeiro lugar as mulheres mais importantes dessa família, as matricarias, responsáveis por todo amor e afeto que existe nessa vida, minha mãe Sônia Regina, minha avó Maria do Carmo, minha irmã Aida Luiza e a minha sobrinha, que chegou em meio a todo esse processo, pequena Alice. Também agradeço a meu pai Wlamir, meu irmão Victor e meu avô, que partiu em meio ao processo, Sérgio Visini. Agradeço as grandes amigas de longa data, Ana Carolina, Nina Vieira, Maiara, Gabriel, Mylena, André, e minha prima e amiga querida, Michelle. As amigas de nova data também, Camille, Raabe, Akene, Susi, Bruna, Thiaga. Agradeço as duas mulheres que foram minhas companheiras durante o processo, Jamille Ribeiro e Kimmy Simões, por terem segurado a barra que é gostar de uma pesquisadora independente de um tema tão controverso em um país como o Brasil, que conta com um sistema acadêmico que adoece milhares de alunos todos os anos pelas suas pressões em produtividade e a baixíssima assistência financeira e psicológica, eles dirão que é uma questão de meritocracia, e eu vos direi que é uma questão de privilégios. -

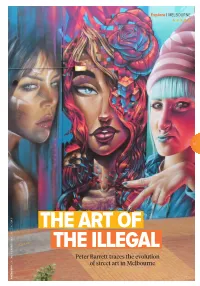

The Art of the Illegal

COMING TO MELBOURNE THIS SUMMER Explore I MELBOURNE Evening Standard 63 THE ART OF ADNATE, SOFLES AND SMUG ADNATE, ARTISTS THE ILLEGAL 11 JAN – 18 FEB PRESENTED BY MTC AND ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE Peter Barrett traces the evolution ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE DEAN SUNSHINE of street art in Melbourne Photo of Luke Treadaway by Hugo Glendinning Photo of Luke Treadaway mtc.com.au | artscentremelbourne.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY Curious-Jetstar_FP AD_FA.indd 1 1/12/17 10:37 am Explore I MELBOURNE n a back alley in Brunswick, a grown man is behaving like a kid. Dean Sunshine should be running his family textiles business. IInstead, the lithe, curly-headed 50-year-old is darting about the bluestone lane behind his factory, enthusiastically pointing out walls filled with colourful artworks. It’s an awesome, open-air gallery, he says, that costs nothing and is in a constant state of flux. Welcome to Dean’s addiction: the ephemeral, secretive, challenging, and sometimes confronting world of Melbourne street art and graffiti. Over the past 10 years, Dean has taken more than 25,000 photographs and produced two + ELLE TRAIL, VEXTA ART SILO DULE STYLE , ADNATE, AHEESCO, books (Land of Sunshine and artist, author and educator, It’s an awesome, Street Art Now) documenting Lou Chamberlin. Burn City: ARTISTS the work of artists who operate Melbourne’s Painted Streets open-air gallery, 64 in a space that ranges from a presents a mind-boggling legal grey area to a downright diversity of artistic expression, he says, that costs illegal one. “I can’t drive along a from elaborate, letter-based street without looking sideways aerosol “pieces” to stencils, nothing and is in down a lane to see if there’s portraits, “paste-ups” (paper something new there,” he says. -

Lindsey Mancini Street Art's Conceptual Emergence

30 NUART JOURNAL 2019 VOLUME 1 NUMBER 2 30–35 GRAFFITI AS GIFT: STREET ART’S CONCEPTUAL EMERGENCE Lindsey Mancini Yale School of Art Drawing primarily on contemporary public discourse, this article aims to identify a divergence between graffiti and street art, and to establish street art as an independent art movement, the examples of which can be identified by an artist’s desire to create a work that offers value – a metric each viewer is invited to assess for themselves. While graffiti and street art are by no means mutually exclusive, street art fuses graffiti’s subversive reclamation of space with populist political leanings and the art historically- informed theoretical frameworks established by the Situationists and Dadaism. Based on two founding principles: community and ephemerality, street art is an attempt to create a space for visual expression outside of existing power structures, weaving it into the fabric of people’s daily lives. GRAFFITI AS GIFT 31 AN INTRODUCTION (AND DISCLAIMER) Hagia Sophia in Turkey; Napoleon's troops have been Attempting to define any aspect of street art or graffiti described as defacing the Sphinx in the eighteenth century; may seem an exercise in futility – for, as is the case with and during World War II, cartoons featuring a long-nosed most contemporary cultural contexts, how can we assess character alongside the words ‘Kilroy was here’, began something that is happening contemporaneously and appearing wherever U.S. servicemen were stationed (Ross, constantly evolving? – but the imperative to understand 2016: 480). In the eighteenth century, English poet Lord what is arguably the most pervasive art movement of the Byron engraved his name into the ancient Greek temple to twenty-first century outweighs the pitfalls of writing Poseidon on Cape Sounion – a mark now described as ‘a something in perpetual danger of becoming outdated. -

September 4Th September 5Th

facebook.com/nolimitboras @nolimitboras @nolimitboras During 4-7th of September the city of Borås will turn into a gigant outdoor gallery Abecita Art Museum) the city has now opened it´s walls to the mural culture. This art created by 11 internationally well known street artists representing 8 different movement, which began with artists painting murals illegally, is now being embraced countries (The Netherlands, France, Brasil, Italy, Germany, Poland, Spain and Sweden). by the public and is letting artists turn Borås into beautiful public spaces that are The artists, some of which have been painting graffiti and street-art as far back as blanketed by artwork of artists worldwide. 1981, are bringing a wide range of talent to Sweden. The walls, which the artists will be painting over the course of the four days long event, reaches as high as 7-storey The murals that will decorate the city of Borås are hopefully here to stay for a long time buildnings. to be enjoyed by many. Borås, with it´s history in opening it´s doors to art (from the International Sculpture A warm welcome to No Limit Street Art Borås – don´t forget to share your experience Biennale to it´s extensive exhibitions at the Borås Museum of Modern Art and on social media! BLEK LE RAT (pronounced: [blзk le KOBRA Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra The program will be updated continously – please check nolimitboras.com for updates ʁa]; born Xavier Prou, 1952) was one utilizes bright colors and bold lines whi- and more info. of the first graffiti artists in Paris, and le staying true to a kaleidoscope theme has been described as the “Father of throughout his art. -

Street Art: Lesson What Is Street Art? 9 How Is It Diferent from Grafti? Why Can It Be Perceived As Controversial?

Street Art: Lesson What is Street Art? 9 How is it diferent from Grafti? Why can it be perceived as controversial? LESSON OVERVIEW/OBJECTIVES Students will learn about Street Art, its history and evolution. They will explore the differences between Street Art and Graffti and talk about why Street Art can be controversial. Students will learn about a well known street artist named Banksy and his work and style as well as look at samples of street art from aroud the world. Students will use stencils, paints and pens to create their own personal brand in the form of street art. KEY IDEAS THAT CONNECT TO VISUAL ARTS CORE CURRICULUM: Based on Utah State Visual Arts Core Curriculum Requirements (3rd Grade) Standard 1 (Making): The student will explore and refne the application of media, techniques, and artistic processes. Objective 1: Explore a variety of art materials while learning new techniques and processes. b. Use simplifed forms, such as cones, spheres, and cubes, to begin drawing more complex forms. d. Make one color dominant in a painting. e. Create the appearance of depth by drawing distant objects smaller and with less detail than objects in the foreground. Objective 3: Handle art materials in a safe and responsible manner. a. Ventilate the room to avoid inhaling fumes from art materials. b. Dispose and/or recycle waste art materials properly. c. Clean and put back to order art making areas after projects. d. Respect other students’ artworks as well as one’s own. Standard 2 (Perceiving): The student will analyze, refect on, and apply the structures of art.