Stretching and Splinting Devices for the Treatment of Joint Stiffness and Contractures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Name of Blue Advantage Policy: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Policy #: 076 Latest Review Date: November 2020 Category: Medical Policy Grade: A BACKGROUND: Blue Advantage medical policy does not conflict with Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), Local Medical Review Policies (LMRPs) or National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) or with coverage provisions in Medicare manuals, instructions or operational policy letters. In order to be covered by Blue Advantage the service shall be reasonable and necessary under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, Section 1862(a)(1)(A). The service is considered reasonable and necessary if it is determined that the service is: 1. Safe and effective; 2. Not experimental or investigational*; 3. Appropriate, including duration and frequency that is considered appropriate for the service, in terms of whether it is: • Furnished in accordance with accepted standards of medical practice for the diagnosis or treatment of the patient’s condition or to improve the function of a malformed body member; • Furnished in a setting appropriate to the patient’s medical needs and condition; • Ordered and furnished by qualified personnel; • One that meets, but does not exceed, the patient’s medical need; and • At least as beneficial as an existing and available medically appropriate alternative. *Routine costs of qualifying clinical trial services with dates of service on or after September 19, 2000 which meet the requirements of the Clinical Trials NCD are considered reasonable and necessary by Medicare. Providers should bill Original Medicare for covered services that are related to clinical trials that meet Medicare requirements (Refer to Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Chapter 1, Section 310 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual Chapter 32, Sections 69.0-69.11). -

The Painful Heel Comparative Study in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reiter's Syndrome, and Generalized Osteoarthrosis

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.36.4.343 on 1 August 1977. Downloaded from Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 1977, 36, 343-348 The painful heel Comparative study in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthrosis J. C. GERSTER, T. L. VISCHER, A. BENNANI, AND G. H. FALLET From the Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland SUMMARY This study presents the frequency of severe and mild talalgias in unselected, consecutive patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, and generalized osteoarthosis. Achilles tendinitis and plantar fasciitis caused a severe talalgia and they were observed mainly in males with Reiter's syndrome or ankylosing spondylitis. On the other hand, sub-Achilles bursitis more frequently affected women with rheumatoid arthritis and rarely gave rise to severe talalgias. The simple calcaneal spur was associated with generalized osteoarthrosis and its frequency increased with age. This condition was not related to talalgias. Finally, clinical and radiological involvement of the subtalar and midtarsal joints were observed mainly in rheumatoid arthritis and occasionally caused apes valgoplanus. copyright. A 'painful heel' syndrome occurs at times in patients psoriasis, urethritis, conjunctivitis, or enterocolitis. with inflammatory rheumatic disease or osteo- The antigen HLA B27 was present in 29 patients arthrosis, causing significant clinical problems. Very (80%O). few studies have investigated the frequency and characteristics of this syndrome. Therefore we have RS 16 PATIENTS studied unselected groups of patients with rheuma- All of our patients had the complete triad (non- toid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), gonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis). -

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis Page 1 of 62 and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Medical Policy An Independent licensee of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Title: Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT) for Plantar Fasciitis and Other Musculoskeletal Conditions Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: July 11, 2001 Original Effective Date: July 1, 2005 Revision Date(s): November 5, 2001; Revision Date(s): December 15, 2005; June 14, 2002; June 13, 2003; October 26, 2012; May 7, 2013; January 28, 2004; June 10, 2004; April 15, 2014; April 14, 2015; April 21, 2005; December 15, 2005; August 4, 2016; January 1, 2017; October 26, 2012; May 7, 2013; August 10, 2017; August 1, 2018; April 15, 2014; April 14, 2015; July 17, 2019, March 11, 2021 August 4, 2016; January 1, 2017; August 10, 2017; August 1, 2018; July 17, 2019, March 11, 2021 Current Effective Date: August 10, 2017 Current Effective Date: August 10, 2017 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. Medical Policy for FEP members is subject to FEP medical policy which may differ from BCBSKS Medical Policy. The medical policies do not constitute medical advice or medical care. -

Advice and Exercises for Patients with Plantar Fasciitis

Advice and exercises for patients with plantar fasciitis This leaflet provides management advice and exercises for people diagnosed with plantar fasciitis, a condition causing pain in the heel, sole and /or arch of the foot. Structures of the foot The plantar fascia is a sheet or broad band of fibrous tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot. This tissue connects the heel to the base of the toes. Under normal circumstances, the plantar fascia supports the arch of the foot and acts as a shock absorbing “bow string” within the arch of the foot. With weight bearing, the foot flattens and the plantar fascia stretches, then springing you forward ready for the next step. While walking, the stresses placed on the foot can be one and a quarter times your body weight (this increases to two and three quarter times your body weight when running). Unsurprisingly then, that heel pain is common. If tension on this “bowstring” becomes too great, irritation or inflammation can occur causing pain. What is plantar fasciitis? Plantar fasciitis is a relatively common foot problem affecting up to 10-15% of the population. It can occur at any age. It is sometimes known as “policeman’s heel”. When placed under too much stress due to abnormal loading, the plantar fascia stretches causing micro tearing and degeneration of the tissue. It can lead to pain in the heel, across the sole of the foot and sometimes into the arch area of the foot too. These micro tears repair with scar tissue, which is less flexible than the fascia and can cause the problem to persist for many months. -

Plantar Fasciitis

Recent Advances in Orthotic Therapy for Plantar Fasciitis An Evidence Based Approach Lawrence Z. Huppin, D.P.M. Assistant Clinical Professor, Western University of Health Sciences, College of Podiatric Medicine Disclosures I disclose the following financial relationships with commercial entities that produce health care related products and services relevant to the content of this lecture: ◦ Employee (Medical Director) of ProLab Orthotics, manufacturer of foot orthoses Our Goals . Review Three Studies that Help Optimize Clinical Outcome of Custom Foot Orthoses Used to Treat Plantar Fasciitis • Cause of Plantar Fascial Tension • Forefoot Wedging Effect on Plantar Fascial Tension • Arch Contour Effect on Plantar Fascial Tension . Develop a “pathology specific” orthosis prescription to most effectively treat plantar fasciitis . Offloading Excessive Fascia Tension is Goal of Orthotic Therapy . What Causes Tension? Tissue Stress Theory McPoil, Hunt. Evaluation and Management of Foot and Ankle Disorders: Present Problems and Future Directions. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 1995 Effect of STJ Pronation on PF Strain . Cannot by itself cause strain of plantar fascia . Can only increase plantar fascia strain via the MTJ • (inversion of the forefoot on the rearfoot) Scherer. “Heel Pain Syndrome: Pathomechanics and Non-surgical Treatment. JAPMA 1991 Effect of Forefoot Inversion on Plantar Fascial Strain 73 patients with 118 painful heels 91% had foot deformity compensated by supination of long axis of MTJ Out of 118 painful heels 63 had forefoot valgus 33 had everted rearfoot 20 had plantarflexed first ray Scherer 1991 What foot types supinate the MTJ? . 47% forefoot valgus . 24% everted heel . 20% plantarflexed first ray Scherer 1991 What foot types supinate the MTJ? . -

Mcl Injuries

MCL INJURIES Definition Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) injury is an injury to the ligament on the inner part of the knee. This ligament keeps the shin bone (tibia) in place. It can be a stretch, partial tear or complete tear of the ligament. Causes The MCL is usually injured by pressure or stress on the outside part of the knee. A block to the outside part of the knee during football is a common way for this ligament to be injured. It is often injured at the same time as an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury occurs. Symptoms Symptoms of a tear in the medial collateral ligament are: Knee Swelling Locking or catching of the knee with movement Pain and tenderness along the inside of the joint The knee gives way or feels like it is going to give way when it is active or stressed in a certain way First Aid A health care provider should examine your knee. A MCL test will be done to detect looseness of the ligament. This test involves bending the knee to 25 degrees and putting pressure on the outside surface of the knee. Other tests may include: Knee joint x-rays Knee MRI Treatment Includes: Applying ice to the area Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) Raising the knee above heart level You should limit physical activity until the pain and swelling go away. The health care provider may put you on crutches and in a brace to protect the ligament. You may also be told not to put any weight on your knee when you walk. -

Chronic Foot Pain

Revised 2020 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Chronic Foot Pain Variant 1: Chronic foot pain. Unknown etiology. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography foot Usually Appropriate ☢ US foot Usually Not Appropriate O MRI foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ Bone scan foot Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Variant 2: Persistent posttraumatic foot pain. Radiographs negative or equivocal. Clinical concern includes complex regional pain syndrome type I. Next imaging study. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O 3-phase bone scan foot Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI foot without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O US foot Usually Not Appropriate O CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ Variant 3: Chronic metatarsalgia including plantar great toe pain. Radiographs negative or equivocal. Clinical concern includes sesamoiditis, Morton’s neuroma, intermetatarsal bursitis, chronic plantar plate injury, or Freiberg’s infraction. Next imaging study. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI foot without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O US foot May Be Appropriate O MRI foot without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT foot without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢ Bone scan foot May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT foot with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT foot without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Chronic Foot Pain Variant 4: Chronic plantar heel pain. -

The Association Between Plantar Fasciitis and Isolated Gastrocnemius Tightness

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN PLANTAR FASCIITIS AND ISOLATED GASTROCNEMIUS TIGHTNESS Dr Ngenomeulu Tufikifa Nakale BSc (UNAM), MBChB (UKZN) Orthopaedic Registrar University of Witwatersrand Division of Orthopaedic Surgery [email protected] A research report submitted to the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Medicine Johannesburg, May 2018 Declaration I Ngenomeulu Tufikifa Nakale, declare that this Research Report is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the Degree of Master of Medicine in the branch of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other University. ………………………… …05th………day of …June….2018…….in Park town, Johannesburg……… i Dedication This research report is dedicated to my wife, parents and siblings for all their patience and understanding. ii Presentations Podium presentation at the South Africa Orthopaedic Association 66th Annual Congress: 4 – 7 September 2017, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. iii Publications Nakale NT, Strydom A, Saragas NP, Ferrao PNF. Association Between Plantar Fasciitis and Isolated Gastrocnemius Tightness. Foot Ankle Int. 2018; 39 (3): 271– 277 iv Abstract Background: Plantar fasciitis is a painful inflammatory condition affecting the plantar aponeurosis of the foot. An association between plantar fasciitis and isolated gastrocnemius tightness has been postulated in published literature; however there have been few studies to prove this relationship. The aim of this study was to determine the association between plantar fasciitis and isolated gastrocnemius tightness. Material and Methods: This was a prospective cross-sectional cohort study over a three-month period comprising three groups: 45 patients with plantar fasciitis, 117 patients with foot and ankle pathology other than plantar fasciitis and 61 patients without foot and ankle pathology. -

Plantar Fasciitis Thomas Trojian, MD, MMB, and Alicia K

Plantar Fasciitis Thomas Trojian, MD, MMB, and Alicia K. Tucker, MD, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Plantar fasciitis is a common problem that one in 10 people will experience in their lifetime. Plantar fasciopathy is an appro- priate descriptor because the condition is not inflammatory. Risk factors include limited ankle dorsiflexion, increased body mass index, and standing for prolonged periods of time. Plantar fasciitis is common in runners but can also affect sedentary people. With proper treatment, 80% of patients with plantar fasciitis improve within 12 months. Plantar fasciitis is predominantly a clinical diagnosis. Symp- toms are stabbing, nonradiating pain first thing in the morning in the proximal medioplantar surface of the foot; the pain becomes worse at the end of the day. Physical examination findings are often limited to tenderness to palpation of the proximal plantar fascial insertion at the anteromedial calcaneus. Ultrasonogra- phy is a reasonable and inexpensive diagnostic tool for patients with pain that persists beyond three months despite treatment. Treatment should start with stretching of the plantar fascia, ice massage, and nonsteroidal anti-inflamma- tory drugs. Many standard treatments such as night splints and orthoses have not shown benefit over placebo. Recalcitrant plantar fasciitis can be treated with injections, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, or surgical procedures, although evidence is lacking. Endoscopic fasciotomy may be required in patients who continue to have pain that limits activity and function despite exhausting nonoperative treatment options. (Am Fam Physician. 2019; 99(12):744-750. Copyright © 2019 American Academy of Family Physicians.) Illustration by Todd Buck Plantar fasciitis (also called plantar fasciopathy, reflect- than 27 kg per m2 (odds ratio = 3.7), and spending most ing the absence of inflammation) is a common problem of the workday on one’s feet 4,5 (Table 1 6). -

Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate and Hydroxyapatite Crystals in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis: a Case Report Shereen R

Case report 91 Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate and hydroxyapatite crystals in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report Shereen R. Kamel Department of Rheumatology and The association between rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and calcium pyrophosphate Rehabilitation, Minia University, Egypt dihydrate (CPPD) crystal deposits can now be easily identified by MSUS, which is a Correspondence to Shereen R Kamel, MD, noninvasive technique that can be applied to patients with painful joints and Department of Rheumatology and enthesis that are unexplained by rheumatoid activity. In this paper, we report an Rehabilitation, Minia University, Minia 6111, Egyptian case of a 51-year-old man who had rheumatoid arthritis since 7 years and Egypt ’ Tel: +20 106 580 0025; developed bilateral knee and heel pain of 1.5 months duration with gradual onset e-mail: [email protected] and progressive course. Radiography revealed features of RA in both hands, as well as features of severe osteoarthritis in both knees with no signs of Received 2 October 2016 Accepted 7 February 2017 chondrocalcinosis. Ultrasonography of the joints, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia detected knee, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia calcifications, which Egyptian Rheumatology & Rehabilitation 2017, 44:91–94 are characteristic of CPPD, and supraspinatus calcification, which is characteristic of hydroxyapatite (HA) deposition. Further investigations revealed no evidence of metabolic disorders. CPPD and HA crystals were identified in his synovial fluid. Subclinical affection with CPPD and HA crystals in RA can be easily detected by ultrasonography, which allows early management to prevent future attacks in RA patients that could lead to exacerbation of joint symptoms that may be missed as rheumatoid disease activity. -

Sesamoiditis MTP Version 16.1.Pages

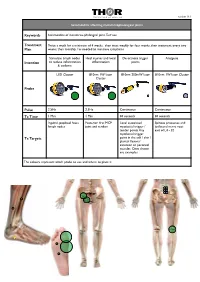

THOR logo 450 WIDE.pdf 26/9/07 22:55:23 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K version 16.1 Sesamoiditis affecting metatarsophalangeal joints Keywords Sesamoiditis of metatarso-phalangeal joint, Turf toe Treatment Twice a week for a minimum of 4 weeks, then treat weekly for four weeks, then treatment every two Plan weeks, then monthly / as needed to minimise symptoms Stimulate lymph nodes Heal injuries and local De-activate trigger Analgesia Intention to reduce inflammation inflammation points & oedema LED Cluster 810nm 1W laser 810nm 200mW laser 810nm 1W laser Cluster Cluster Probe Pulse 2.5Hz 2.5Hz Continuous Continuous Tx Time 1 Min 1 Min 30 seconds 30 seconds Inguinal, popliteal fossa Posterior first MCP Local associated Spinous processes and lymph nodes joint and tendon myofascial trigger / ipsilateral nerve root tender points Any exit of L4 - S2 myofascial trigger Tx Targets point in the calf / shin / plantar flexors/ extensor or peroneal muscles. Ones shown are examples The colours represent which probe to use and where to place it THOR logo 450 WIDE.pdf 26/9/07 22:55:23 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Specific Evidence: A systematic review of low level laser therapy with location-specific doses for pain from chronic joint disorders. Bjordal JM, Couppe C, Chow RT, Tuner J, Ljunggren EA Aust J Physiother 2003 49(2) 107-16 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi? cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12775206 General evidence across disease category: Inflammation - tendons, fascia, soft tissue injuries Kiritsi O, Tsitas K, Malliaropoulos N, Mikroulis G. -

Foot Pain & Psoriatic Arthritis

WHEATON • ROCKVILLE • CHEVY CHASE • WASHINGTON, DC Foot Pain & Psoriatic Arthritis Daniel El-Bogdadi, MD, FACR Arthritis and Rheumatism Associates, P.C. Do you feel heel pain in the Plantar fasciitis ARTHRITIS morning or after a period of can be caused by inactivity? This might be an a number AND indication of plantar fasciitis that of factors, RHEUMATISM could be part of an underlying including aerobic ASSOCIATES, P.C. psoriatic arthritis condition. dance exercise, running, and Board Certified Rheumatologists Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory ballet. arthritis that typically causes pain, Herbert S.B. Baraf MD FACP MACR swelling and stiffness in the Robert L. Rosenberg peripheral joints or spine. However, MD FACR CCD if you have psoriatic arthritis, you Evan L. Siegel may notice that not only are the MD FACR joints and spine involved, but Emma DiIorio symptoms may also occur in the soft MD FACR tissue such as tendons or ligaments. David G. Borenstein MD MACP MACR This usually happens in a place Alan K. Matsumoto where tendons and ligaments attach There are several treatment options MD FACP FACR to bone, known as the enthesis. for plantar fasciitis: David P. Wolfe When this attachment gets inflamed MD FACR it is called enthesitis. • The first immediate intervention is Paul J. DeMarco MD FACP FACR to decrease or stop any Shari B. Diamond One of the more common areas to repetitive activities, such as MD FACP FACR get enthesitis is in the Achilles running or dancing, which may Ashley D. Beall tendon. Another common area for aggravate the condition. MD FACR inflammation is in thick band of (over) Angus B.