Colijn De Coter, the Lamentation (Pietà), Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instructions and Techniques *

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Discoloration in Renaissance and Baroque Oil Paintings. Instructions for Painters, theoretical Concepts, and Scientific Data van Eikema Hommes, M.H. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Eikema Hommes, M. H. (2002). Discoloration in Renaissance and Baroque Oil Paintings. Instructions for Painters, theoretical Concepts, and Scientific Data. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 Verdigriss Glazes in Historical Oil Paintings: Instructions and Techniques * 'Lje'Lje verdegris distillépourglacer ne meurt point? Dee Mayerne (1620-46), BL MS Sloane 2052 'Vert'Vert de gris... ne dure pas & elk devient noire.' Dee la Hire, 1709 InterpretationInterpretation of green glares Greenn glazes were commonly used in oil paintings of the 15th to 17th centuries for the depiction of saturated greenn colours of drapery and foliage. -

The Early Netherlandish Underdrawing Craze and the End of a Connoisseurship Era

Genius disrobed: The Early Netherlandish underdrawing craze and the end of a connoisseurship era Noa Turel In the 1970s, connoisseurship experienced a surprising revival in the study of Early Netherlandish painting. Overshadowed for decades by iconographic studies, traditional inquiries into attribution and quality received a boost from an unexpected source: the Ph.D. research of the Dutch physicist J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer.1 His contribution, summarized in the 1969 article 'Reflectography of Paintings Using an Infrared Vidicon Television System', was the development of a new method for capturing infrared images, which more effectively penetrated paint layers to expose the underdrawing.2 The system he designed, followed by a succession of improved analogue and later digital ones, led to what is nowadays almost unfettered access to the underdrawings of many paintings. Part of a constellation of established and emerging practices of the so-called 'technical investigation' of art, infrared reflectography (IRR) stood out in its rapid dissemination and impact; art historians, especially those charged with the custodianship of important collections of Early Netherlandish easel paintings, were quick to adopt it.3 The access to the underdrawings that IRR afforded was particularly welcome because it seems to somewhat offset the remarkable paucity of extant Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the fifteenth century. The IRR technique propelled rapidly and enhanced a flurry of connoisseurship-oriented scholarship on these Early Netherlandish panels, which, as the earliest extant realistic oil pictures of the Renaissance, are at the basis of Western canon of modern painting. This resulted in an impressive body of new literature in which the evidence of IRR played a significant role.4 In this article I explore the surprising 1 Johan R. -

PENDERECKI Utrenja

572031 bk Penderecki 4/2/09 16:15 Page 8 Stanisław Skrowaczewski, and in 1958 Witold Rowicki was again appointed artistic director and principal conductor, a post he held until 1977, when he was succeeded by Kazimierz Kord, serving until the end of the centenary celebrations in 2001. In 2002 Antoni Wit became general and artistic director of the Warsaw PENDERECKI Philharmonic – The National Orchestra and Choir of Poland. The orchestra has toured widely abroad, in addition to its busy schedule at home in symphony concerts, chamber concerts, educational work and other activities. It now has a complement of 110 players. Utrenja Antoni Wit Hossa • Rehlis • Kusiewicz • Nowacki • Bezzubenkov Antoni Wit, one of the most highly regarded Polish conductors, studied conducting with Henryk Czyz and composition with Krzysztof Penderecki Warsaw Boys’ Choir at the Academy of Music in Kraków, subsequently continuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He also graduated in law at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Immediately after completing his studies he was Warsaw Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra engaged as an assistant at the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra by Witold Rowicki and was later appointed conductor of the Poznan Philharmonic, Antoni Wit collaborated with the Warsaw Grand Theatre, and from 1974 to 1977 was artistic director of the Pomeranian Philharmonic, before his appointment as director of the Polish Radio and Television Orchestra and Chorus in Kraków, from 1977 to 1983. From 1983 to 2000 he was the director of the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, and from 1987 to 1992 he was the chief conductor and then first guest conductor of Orquesta Filarmónica de Gran Canaria. -

'A Man of Sorrows, and Acquainted with Grief'

‘A Man of Sorrows, and Acquainted with Grief’ Imagery of the Suffering Christ in the Art of the Late Medieval Low Countries and Counter-Reformation Spain Candidate Number: R2203 MA Art History, Curatorship and Renaissance Culture The Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study 30/09/2015 Word Count: 14,854 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: The Man of Sorrows – A Reassessment 6 Chapter 2: Early Netherlandish Images of the Suffering Christ 14 Chapter 3: Counter-Reformation Spanish Polychrome Sculptures 21 Chapter 4: Comparison and Analysis: Netherlandish Influences on Spanish Polychrome Sculpture 27 Conclusion 35 Figures 37 Table of Figures 56 Bibliography 58 2 Introduction During the later Middle Ages in Europe, there was a great increase in private devotion: a rise in the production of Books of Hours, the increase of mendicant orders and the new development of private chapels in churches and cathedrals all contributed towards religion being much more personal and intimate than ever before.1 Especially in Northern Europe, where the Imitatio Christi of Thomas à Kempis2 gained previously unknown popularity, private devotion was encouraged. The Devotio Moderna, which took hold especially in the Low Countries and Germany, emphasised a systematic and personal approach to prayer.3 Devotional images, which could engage with believers on a one-on-one, personal level, were majorly important features of way of practising religion, and the use of images as foci for devotion was encouraged by many writers, not only Thomas à Kempis, but also -

Lamentation of Christ

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes Lamentation of Christ Painted about 1767/68. Oil on cartoon on canvas. Measurements: 35 x 23 cm (13 ³/ x 9 inches) Description We are facing a picture representing a Lamentation of Christ whose authorship is unanimously assigned to Goya in the catalogues by Gudiol 1970 n8 /1980 n5; Gassier & Wilson1970 n8/1984 n12; De Angelis 1974 /76 n19; Camón Aznar 1980 pág. 42; Xavier de Salas 1984 n9; J.L. Morales 1990 n6 / 1997 n3; Arturo Ansón "Goya y Zaragoza" 1995 pág. 61; catalogue online Fundación Goya y Aragón, año 2012. All these authors coincide in dating this work between 1768 and 1770, just before his journey to Italy, and in considering it one of the devotional paintings young Goya carried out at Fuendetodos. This would coincide with his origin of having belonged, according to Gudiol, to a family of Fuendetodos. The IOMR has made a comparative study of the painting in which we point out its stylistic analogies with other works by Goya: The immediacy and reality with which the painter treats the scene so that one may feel it close to life and real, where the artist reveals the human pathos of death with no conventional mannerisms, excluding figures of the celestial world, such as angels, which might confuse his pure sense of reality so that what first surprises one in the picture and what, in fact, makes it closer to Goya and therefore reminds one of the engraving, Desastre Nº 26 No se puede mirar and Nº 14 of the same series, Duro es el paso in which Goya treats death with a completely contemporary closeness. -

A Triptych of the Flagellation with Saint Benedict and Saint Bernard from the Workshop of Jan Van Dornicke in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

A Triptych of the Flagellation with Saint Benedict and Saint Bernard from the workshop of Jan van Dornicke in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum Ana Diéguez Rodríguez This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford: fig. 4 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1-3, 5 and 8-9 © Iziko Museum of South Africa: fig. 7 © Staatsgalerie Stuttgart: fig. 6 Text published in: Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 9, 2015, pp. 51-72. Sponsor: 2 art of the exceptional collection of Flemish painting at the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, this small triptych has the Flagellation of Christ for its central theme and portrayals of two Benedictine saints, Saint Be- Pnedict and Saint Bernard on the lateral wings [fig. 1]1. It is unusual both for the combination of themes and for the lack of any spatial consistency between them, there being no uniting feature between the main scene, shown in an interior, and the laterals, both situated in landscapes. -

The Evolution of Landscape in Venetian Painting, 1475-1525

THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 by James Reynolds Jewitt BA in Art History, Hartwick College, 2006 BA in English, Hartwick College, 2006 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by James Reynolds Jewitt It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by C. Drew Armstrong, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by James Reynolds Jewitt 2014 iii THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 James R. Jewitt, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 Landscape painting assumed a new prominence in Venetian painting between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century: this study aims to understand why and how this happened. It begins by redefining the conception of landscape in Renaissance Italy and then examines several ambitious easel paintings produced by major Venetian painters, beginning with Giovanni Bellini’s (c.1431- 36-1516) St. Francis in the Desert (c.1475), that give landscape a far more significant role than previously seen in comparable commissions by their peers, or even in their own work. After an introductory chapter reconsidering all previous hypotheses regarding Venetian painters’ reputations as accomplished landscape painters, it is divided into four chronologically arranged case study chapters. -

Ana Diéguez-Rodríguez the Artistic Relations Between Flanders and Spain in the 16Th Century: an Approach to the Flemish Painting Trade

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 2 (2019) Ana Diéguez-Rodríguez The artistic relations between Flanders and Spain in the 16th Century: an approach to the Flemish painting trade ABSTRACT Such commissions were received by important workshops and masters with a higher grade of This paper discusses different ways of trading quality. As the agent, the intermediary had to between Flanders and Spain in relation to take care of the commission from the outset to paintings in the sixteenth century. The impor- the arrival of the painting in Spain. Such duties tance of local fairs as markets providing luxury included the provision of detailed instructions objects is well known both in Flanders and and arrangement of shipping to a final destina- in the Spanish territories. Perhaps less well tion. These agents used to be Spanish natives known is the role of Flemish artists workshops long settled in Flanders, who were fluent in in transmitting new models and compositions, the language and knew the local trade. Unfor- and why these remained in use for longer than tunately, very little correspondence about the others. The article gives examples of strong commissions has been preserved, and it is only networks among painters and merchants the Flemish paintings and altarpieces pre- throughout the century. These agents could served in Spanish chapels and churches which also be artists, or Spanish merchants with ties provide information about their workshop or in Flanders. The artists become dealers; they patron. would typically sell works by their business Last, not least it is necessary to mention the partners not only on the art markets but also Iconoclasm revolt as a reason why many high in their own workshops. -

The Holy Family with Two Saints, a Work from the Workshop of the Master of the Antwerp Adoration

The Holy Family with Two Saints, a work from the workshop of the Master of the Antwerp Adoration Catheline Périer–D’Ieteren This text is published under an international Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY–NC–ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by–ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa–Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Adri Verburg / Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp: figs. 16, 17 and 18 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa–Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 6–15, 22, 25, 28, 31, 33 and 39 © Christie’s Images / The Bridgeman Art Library Nationality: fig. 36 Cortesía Catheline Périer–D’leteren: figs. 24, 27, 30, 32 and 34 Cortesía Peter van den Brink: fig. 35 © Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, The Netherlands: fig. 2 © Picture Library. Ashmolean Museum: fig. 20 © Prof. Dr. J.R.J. van Asperen de Boer / RKD, The Hague. Infrared reflectography was performed with a Grun- dig FA 70 television camera equipped with a Hamamatsu N 214 IR vidicon (1975); a Kodak wratten 87A filter cutting–on at 0.9 micron was placed between the vidicon target surface and the Zoomar 1:2 8/4 cm Macro Zoomatar lens. -

Niccolò Di Pietro Gerini's 'Baptism Altarpiece'

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 33 National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2012 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including CHICAGO photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence: prior permission in writing from the publisher. fi g. 9, p. 77. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence © Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library: fi g. 45, p. 45; © 2012. Photo Scala, First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali: fig. 43, p. 44. National Gallery Company Limited St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street LONDON London WC2H 7HH The British Library, London © The British Library Board: fi g. 15, p. 91. www.nationalgallery. co.uk MUNICH Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record is available from the British Library. © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence/BPK, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin: fig. 47, p. 46 (centre pinnacle); fi g. 48, p. 46 (centre ISBN: 978 1 85709 549 4 pinnacle). -

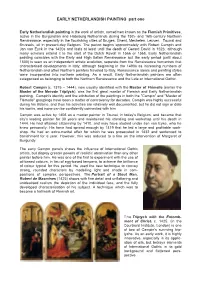

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING Part One

EARLY NETHERLANDISH PAINTING part one Early Netherlandish painting is the work of artists, sometimes known as the Flemish Primitives, active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance, especially in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Leuven, Tounai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium. The period begins approximately with Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck in the 1420s and lasts at least until the death of Gerard David in 1523, although many scholars extend it to the start of the Dutch Revolt in 1566 or 1568. Early Netherlandish painting coincides with the Early and High Italian Renaissance but the early period (until about 1500) is seen as an independent artistic evolution, separate from the Renaissance humanism that characterised developments in Italy; although beginning in the 1490s as increasing numbers of Netherlandish and other Northern painters traveled to Italy, Renaissance ideals and painting styles were incorporated into northern painting. As a result, Early Netherlandish painters are often categorised as belonging to both the Northern Renaissance and the Late or International Gothic. Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), now usually identified with the Master of Flémalle (earlier the Master of the Merode Triptych), was the first great master of Flemish and Early Netherlandish painting. Campin's identity and the attribution of the paintings in both the "Campin" and "Master of Flémalle" groupings have been a matter of controversy for decades. Campin was highly successful during his lifetime, and thus his activities are relatively well documented, but he did not sign or date his works, and none can be confidently connected with him. -

Natee Utarit Demetrio Paparoni

Natee Utarit Demetrio Paparoni NATEE UTARIT Optimism is Ridiculous Contents Cover and Back Cover First published in Italy in 2017 by Photo Credits Special thanks for their support 6 The Perils of Optimism. Passage to the Song of Truth Skira editore S.p.A. © 2017. DeAgostini Picture Library/ and collaboration to and Absolute Equality, 2014 Palazzo Casati Stampa Scala, Firenze: pp. 14 (top), 76, 102 The Art of Natee Utarit (details) via Torino 61 © 2017. Digital image, The Museum Demetrio Paparoni 20123 Milano of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Art Director Italy Firenze: pp. 14 (bottom), 18, Makati Avenue corner Marcello Francone www.skira.net 124 (bottom) De La Rosa Street, Greenbelt Park, Makati City, 147 © 2017. Foto Austrian Archives/ 1224 Philippines Optimism is Ridiculous Design © All rights reserved by Richard Koh Scala, Firenze: p. 90 Luigi Fiore Fine Art, Singapore © 2017. Foto Joerg P. Anders. © 2017 Skira editore for this edition Editorial Coordination Foto Scala, Firenze/bpk, Bildagentur 241 Writings by the Artist © 2017 Demetrio Paparoni for his Vincenza Russo fuer Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, text Berlin: p. 134 Editing © 2017 Natee Utarit for his works © 2017. Foto Klaus Goeken. 249 Appendix Valeria Perenze and texts Foto Scala, Firenze/bpk, Bildagentur © Joseph Beuys, Juan Muñoz, Layout fuer Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, by SIAE 2017 Antonio Carminati Berlin: p. 82 Jl. Medan Merdeka Timur No. 14 © Man Ray Trust, by SIAE 2017 Jakarta Pusat 10110 - Indonesia © 2017. Foto Scala, Firenze: pp. 8, Translation © Succession Marcel Duchamp 29 (top left), 34, 48, 116 Natalia Iacobelli by SIAE 2016 © 2017. Foto Scala, Firenze/bpk, © Succession Picasso, by SIAE 2017 Iconographical Research Bildagentur fuer Kunst, Kultur © The Andy Warhol Foundation for Paola Lamanna und Geschichte, Berlin: pp.